Cholecystectomy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Cholecystectomy | |

|---|---|

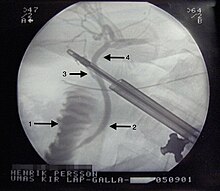

X-Ray during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. 1 - Duodenum. 2 - Common bile duct. 3 - Cystic duct. 4 - Hepatic duct. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 575.0 |

| MeSH | D002763 |

Cholecystectomy (/ˌkɒləsɪsˈtɛktəmi/; plural: cholecystectomies) is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. It is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. Surgical options include the standard procedure, called laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and an older, more invasive procedure, called open cholecystectomy. The surgery can lead to postcholecystectomy syndrome.

Indications

Indications for cholecystectomy include inflammation of the gall bladder (cholecystitis), biliary colic, risk factors for gall bladder cancer,[1] and pancreatitis caused by gall stones.

Cholecystectomy is the recommended treatment the first time a person is admitted to hospital for cholecystitis.[2] Cholecystitis may be acute or chronic, and may or may not involve the presence of gall stones. Risk factors for gall bladder cancer include a "porcelain gallbladder," or calcium deposits in the wall of the gall bladder, and an abnormal pancreatic duct.[1]

Cholecystectomy can prevent the relapse of pancreatitis that is caused by gall stones that block the common bile duct.[3]

Procedure

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has now replaced open cholecystectomy as the first-choice of treatment for gallstones and inflammation of the gallbladder unless there are contraindications to the laparoscopic approach. This is because open surgery leaves the patient more prone to infection.[4] Sometimes, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy will be converted to an open cholecystectomy for technical reasons or safety.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy requires several (usually 4) small incisions in the abdomen to allow the insertion of operating ports, small cylindrical tubes approximately 5 to 10 mm in diameter, through which surgical instruments and a video camera are placed into the abdominal cavity. The camera illuminates the surgical field and sends a magnified image from inside the body to a video monitor, giving the surgeon a close-up view of the organs and tissues. The surgeon watches the monitor and performs the operation by manipulating the surgical instruments through the operating ports.

To begin the operation, the patient is placed in the supine position on the operating table and anesthetized. A scalpel is used to make a small incision at the umbilicus. Using either a Veress needle or Hasson technique, the abdominal cavity is entered. The surgeon inflates the abdominal cavity with carbon dioxide to create a working space. The camera is placed through the umbilical port and the abdominal cavity is inspected. Additional ports are opened inferior to the ribs at the epigastric, midclavicular, and anterior axillary positions. The gallbladder fundus is identified, grasped, and retracted superiorly. With a second grasper, the gallbladder infundibulum is retracted laterally to expose and open Calot's Triangle (cystic artery, cystic duct, and common hepatic duct). The triangle is gently dissected to clear the peritoneal covering and obtain a view of the underlying structures. The cystic duct and the cystic artery are identified, clipped with tiny titanium clips and cut. Then the gallbladder is dissected away from the liver bed and removed through one of the ports. This type of surgery requires meticulous surgical skill, but in straightforward cases, it can be done in about an hour.

Recently, new techniques have been developed to perform this surgery through a single incision in the patient's umbilicus. This advanced technique is called Laparoendoscopic Single Site Surgery or "LESS" or Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery or "SILS". In this procedure, instead of making 3-4 four small different cuts (incisions), a single cut (incision) is made through the navel (umbilicus). Through this cut, specialized rotaculating instruments (straight instruments which can be bent once inside the abdomen) are inserted to do the operation. The advantage of LESS / SILS operation is that the number of cuts are further reduced to one and this cut is also not visible after the operation is done as it is hidden inside the navel. A meta-analysis published by Pankaj Garg et al. comparing conventional laparoscopic cholecystecomy to SILS Cholecystectomy demonstrated that SILS does have a cosmetic benefit over conventional four-hole laparoscopic cholecystectomy while having no advantage in postoperative pain and hospital stay.[5] A significantly higher incidence of wound complications, specifically development of hernia, has been noted with SILS.[6] SILS has also been associated with a higher risk for bile duct injury [7]

Laparoscopic bile duct exploration (LBDE) is recommended in current treatment guidelines for the management of choledocholithiasis with gallbladder in situ. Failure of this technique is common as a consequence of large or impacted common bile duct (CBD) stones. A new technique, LABEL (Laser-Assisted Bile duct Exploration by Laparoendoscopy) has been developed to enhance LBDE in cases of impacted or large stones using holmium-laser increasing the feasibility of the transcystic stone retrieval and reducing overall operative time in the treatment of choledocholithiasis.[8]

Open cholecystectomy

Open cholecystectomy is occasionally performed in certain circumstances, such as failure of laparoscopic surgery, severe systemic illness causing intolerance of pneumoperitoneum, or as part of a liver transplant. In open cholecystectomy, a surgical incision of approximately 10 to 15 cm is typically made below the edge of the right ribcage. The liver is retracted superiorly, and a top-down approach is taken (from the fundus towards the neck) to remove the gallbladder from the liver, typically using electrocautery.[9]

Open cholecystectomy is associated with greater post-operative pain and wound complications such as wound infection and incisional hernia compared to laparoscopic cholecystectomy, so it is reserved for select cases.

Procedural risks and complications

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not require the abdominal muscles to be cut, resulting in less pain, quicker healing, improved cosmetic results, and fewer complications such as infection and adhesions. Most patients can be discharged on the same or following day as the surgery, and can return to any type of occupation in about a week.

An uncommon but potentially serious complication is injury to the common bile duct, which connects the cystic and common hepatic ducts to the duodenum. An injured bile duct can leak bile and cause a painful and potentially dangerous infection. Many cases of minor injury to the common bile duct can be managed non-surgically. Major injury to the bile duct, however, is a very serious problem and may require corrective surgery. This surgery should be performed by an experienced biliary surgeon.[10]

Abdominal peritoneal adhesions, gangrenous gallbladders, and other problems that obscure vision are discovered during about 5% of laparoscopic surgeries, forcing surgeons to switch to the standard cholecystectomy for safe removal of the gallbladder. Adhesions and gangrene can be serious, but converting to open surgery does not equate to a complication.

A Consensus Development Conference panel, convened by the National Institutes of Health in September 1992, endorsed laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a safe and effective surgical treatment for gallbladder removal, equal in efficacy to the traditional open surgery. The panel noted, however, that laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed only by experienced surgeons and only on patients who have symptoms of gallstones.

In addition, the panel noted that the outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is greatly influenced by the training, experience, skill, and judgment of the surgeon performing the procedure. Therefore, the panel recommended that strict guidelines be developed for training and granting credentials in laparoscopic surgery, determining competence, and monitoring quality. According to the panel, efforts should continue toward developing a noninvasive approach to gallstone treatment that will not only eliminate existing stones, but also prevent their formation or recurrence.

One common complication of cholecystectomy is inadvertent injury to analogous bile ducts known as Ducts of Luschka, occurring in 33% of the population. It is non-problematic until the gall bladder is removed, and the tiny supravesicular ducts may be incompletely cauterized or remain unobserved, leading to biliary leak post-operatively. The patient will develop biliary peritonitis within 5 to 7 days following surgery, and will require a temporary biliary stent. It is important that the clinician recognize the possibility of bile peritonitis early and confirm diagnosis via HIDA scan to lower morbidity rate. Aggressive pain management and antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as diagnosed.

During laparoscopic cholecystectomy, gallbladder perforation can occur due to excessive traction during retraction or during dissection from the liver bed. It can also occur during extraction from the abdomen. Infected bile, pigment gallstones, male gender, advanced age, perihepatic location of spilled gallstones, more than 15 gallstones and an average size greater than 1.5 cm have been identified as risk factors for complications. Spilled gallstones can be a diagnostic challenge and can cause significant morbidity to the patient. Clear documentation of spillage and explanation to the patient is of utmost importance, as this will enable prompt recognition and treatment of any complications. Prevention of spillage is the best policy.[11]

Biopsy

After removal, the gallbladder should be sent for pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis and look for an incidental cancer. If cancer is present, a reoperation to remove part of the liver and lymph nodes will be required in most cases.[12]

Long-term prognosis

A minority of the population, from 5% to 40%, develop a condition called postcholecystectomy syndrome, or PCS.[13] Symptoms can include gastrointestinal distress and persistent pain in the upper right abdomen.

As many as 20% of patients develop chronic diarrhea. The cause is unclear, but is presumed to involve the disturbance to the bile system. Most cases clear up within weeks or a few months, though in rare cases the condition may last for many years. It can be controlled with medication such as cholestyramine.[14]

Complications

The most serious complication of cholecystectomy is damage to the bile ducts. This occurs in about 0.25% of cases.[2] Damage to the duct that causes leakage typically manifests as fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain several days following cholecystectomy.[2] The treatment of bile duct injuries depends on the severity of the injury, and ranges from biliary stenting via ERCP to the surgical construction of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.[2]

- emphysematous cholecystitis

- bile leak ("biloma")

- bile duct injury (about 5–7 out of 1000 operations. Open and laparoscopic surgeries have essentially equal rate of injuries, but the recent trend is towards fewer injuries with laparoscopy. It may be that the open cases often result because the gallbladder is too difficult or risky to remove with laparoscopy)

- abscess

- wound infection

- bleeding (liver surface and cystic artery are most common sites)

- hernia

- organ injury (intestine and liver are at highest risk, especially if the gallbladder has become adherent/scarred to other organs due to inflammation (e.g. transverse colon)

- deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (unusual- risk can be decreased through use of sequential compression devices on legs during surgery)

- fatty acid and fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption

Postoperative cystic duct stump leaks

A postoperative cystic duct stump leak (CDSL) is a leak from the cystic duct stump in post cholecystectomy patients. It was rarely reported in open cholecystectomy patients. Since the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy the incidence of CDSL has increased with one study indicating that it occurs in 0.1 to 0.2% of patients.[15] Cystic duct stump leak is the commonest cause of bile leak and technical morbidity according to one study.[16] The cause may be not related the presence of emergency laparoscopic cholecystecomies as one study showed that only 46.6% of CDSL occurred with acute cholecystitis.[17]

Theories of the CDSL include:

1. Cystic duct displacement:

- 1a. Improper firing can cause the clip to displace as one study showed clipless cystic ducts after placement of 2 cystic duct clips.[18][19]

- 1b. Cystic duct displacement could be due to abnormal cystic duct morphological features. This could place constrictions which thus could lead to improper firing. A solution is to suture the duct or as last resort leave a T tube or Jackson-pratt drain intraoperatively.

2. Necrosis of cystic duct stump proximal to clip: This would occur proximal to the applied clip. Necrosis may be secondary to electrocautery creating a phenomenon called "clip-coupling" in which excessive electrocautery near the clips, conducted via the metal in the clips, causes necrosis of the proximal cystic duct.[20]

3. Ischemic necrosis secondary to devascularization: One study showed that blood flow can be disrupted from dissecting. One study showed a pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery causing vascular disrupting blood supply to the cystic duct. A solution is dividing the cystic artery distally.[15]

4. Increased biliary pressure: This can be due to a retained common bile duct stone creating pressure in the biliary tree. This may be the most rare causes of CDSL.[15]

CDSL presentation

CDSL presents 3 to 4 days after operation with right upper quadrant pain, followed by nausea, vomiting, and fever. High WBC is described in 68% of patients. Liver function tests can be highly variable.[15]

Diagnosis and treatment of CDSL

Initial test is ultrasonography to screen out biloma, ascites, or retained stones. Computed tomography has a high sensitivity approaching 100% for detecting leaks. The most successful imaging is from ERCP. ERCP has the additional value of allowing for treatment which often consists of sphincterotomy with common bile duct stenting. With endoscopic drainage, CDSLs often resolve without the need for reoperation.

Epidemiology

About 600,000 people receive a cholecystectomy in the United States each year.[21] An Italian research showed that about 100,000 people receive a cholecystectomy in Italy each year,[22] with a complication rate between 1 and 12%, a percentage defined as "significant, taking into account the benignity of the disease".[22]

In a study of Medicaid-covered and uninsured U.S. hospital stays in 2012, cholecystectomy was the most common operating room procedure.[23]

See also

References

- ^ a b Goldman 2011, pp. 1019

- ^ a b c d Goldman, Lee (2011). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 1017. ISBN 1437727883.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Goldman 2011, pp. 940

- ^ Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, Ashley SW (August 1992). "Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new 'gold standard'?". Arch Surg. 127 (8): 917–21, discussion 921–3. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080051008. PMID 1386505.

- ^ Garg P, Thakur JD, Garg M, Menon GR (August 2012). "Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs. conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 16 (8): 1618–28. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-1906-6. PMID 22580841.

- ^ Marks, JM (2013). "Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with improved cosmesis scoring at the cost of significantly higher hernia rates: 1-year results of a prospective randomized, mullticenter, single-blinded trial of traditional multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy". J Am Coll Surg. 216 (6): 1037–47.

- ^ Joseph, M (2012). "Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a higher bile duct injury rate: a review and a word of caution". Ann Surg. 256 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1097/sla.0b013e3182583fde.

- ^ Navarro-Sánchez, Antonio; Ashrafian, Hutan; Segura-Sampedro, Juan José; Martrinez-Isla, Alberto (2016-08-29). "LABEL procedure: Laser-Assisted Bile duct Exploration by Laparoendoscopy for choledocholithiasis: improving surgical outcomes and reducing technical failure". Surgical Endoscopy. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-5206-1. ISSN 1432-2218. PMID 27572062.

- ^ Goldman 2011, pp. 696

- ^ Kapoor VK (2007). "Bile duct injury repair: when? what? who?". J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 14 (5): 476–9. doi:10.1007/s00534-007-1220-y. PMID 17909716.

- ^ Ashwin Rammohan; U.P. Srinivasan; S. Jeswanth; P. Ravichandran (2012). "Inflammatory pseudotumour secondary to spilled intra-abdominal gallstones". Int J Surg Case Rep. 3 (7): 305–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.03.013. PMC 3356557. PMID 22543231.

- ^ Kapoor VK (March 2001). "Incidental gallbladder cancer". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96 (3): 627–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03597.x. PMID 11280526.

- ^ "Postcholecystectomy syndrome". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chronic diarrhea: A concern after gallbladder removal?, Mayo Clinic

- ^ a b c d Eisenstein, Samuel; Greenstein, A. J.; Kim, U; Divino, C. M. (2008). "Cystic Duct Stump Leaks". Archives of Surgery. 143 (12): 1178–83. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.12.1178. PMID 19075169.

- ^ Shaikh, Irshad A. A.; Thomas, Harun; Joga, Kishore; Amin, A. Ibrahim; Daniel, Thomas (August 2009). "Post-cholecystectomy cystic duct stump leak: a preventable morbidity". Journal of Digestive Diseases. 10 (3): 207–212. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00387.x.

- ^ Wise Unger, S; Glick, G. L.; Landeros, M (1996). "Cystic duct leak after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A multi-institutional study". Surgical endoscopy. 10 (12): 1189–93. doi:10.1007/s004649900276. PMID 8939840.

- ^ Hanazaki, K; Igarashi, J; Sodeyama, H; Matsuda, Y (1999). "Bile leakage resulting from clip displacement of the cystic duct stump: A potential pitfall of laparoscopic cholecystectomy". Surgical endoscopy. 13 (2): 168–71. doi:10.1007/s004649900932. PMID 9918624.

- ^ Li, J. H.; Liu, H. T. (2005). "Diagnosis and management of cystic duct leakage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Report of 3 cases". Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international. 4 (1): 147–51. PMID 15730941.

- ^ Woods, M. S.; Shellito, J. L.; Santoscoy, G. S.; Hagan, R. C.; Kilgore, W. R.; Traverso, L. W.; Kozarek, R. A.; Brandabur, J. J. (1994). "Cystic duct leaks in laparoscopic cholecystectomy". American journal of surgery. 168 (6): 560–3, discussion 563–5. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80122-9. PMID 7977996.

- ^ Goldman 2011, pp. 855

- ^ a b Università degli Studi di Pavia, Errore chirurgico, indice di rischio e colecistectomia videolaparoscopica, 2012

- ^ Lopez-Gonzalez L, Pickens GT, Washington R, Weiss AJ (October 2014). "Characteristics of Medicaid and Uninsured Hospitalizations, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #183. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Tsin DA, Colombero LT, Lambeck J, Manolas P.Minilaparoscopy-assisted natural orifice surgery.JSLS. 2007 Jan-Mar;11(1):24-9. PMID 17651552

External links

- Soltes & Radoňak risk score for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy difficulty

- Video of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- "Gallbladder Removal". New York Times. 2007-08-01.

- Information and Photographs of conventional and SILS (LESS) Single Incision Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Education Module for surgical trainees