Cinderalla

| Cinderalla | |

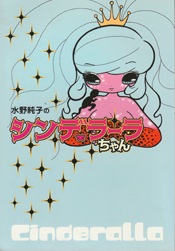

Cover of the Japanese first edition | |

| 水野純子のシンデラーラちゃん (Mizuno Junko no Shinderāra-chan) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Fantasy, Horror |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Junko Mizuno |

| Published by | Koushinsya |

| English publisher | |

| English magazine | Pulp: The Manga Magazine |

| Published | February 2000 |

| Volumes | 1 |

Cinderalla (Japanese: 水野純子のシンデラーラちゃん, Hepburn: Mizuno Junko no Shinderāra-chan), also known as Junko Mizuno's Cinderalla, is a fantasy-horror manga written and illustrated by Junko Mizuno. It was published by Koushinsya; later an English version was released by Viz Media in 2002. It is one in a line of her new version on old fairy tales, the others are Hansel & Gretel and Princess Mermaid. In the English book there is an interview between Izumi Evers and Junko Mizuno. Andy Nakatani has translated the interview into English.

Plot

An adaptation of the fairy tale "Cinderella", Cinderalla focuses on the eponymous protagonist, who works as a waitress in her father's yakitori (skewered chicken) restaurant. One day, he dies from overeating, only to rise again during the night as a zombie. Her father remarries, having fallen in love with another zombie, the ceaselessly hungry Caroline. Cinderalla's elder zombie stepsisters, Akko and Aki, only add to her workload. One day, while searching for the bra that she is making for Aki, she falls in love with a male zombie. Later, she and her mouse friend, Setsuko, rescue a starving fairy from some twin boys planning to dissect her. The fairy reveals that she cannot return to her home until she has gained her magical powers, and Cinderalla allows her to stay at her home.

Eventually, Cinderalla learns that the zombie she loves is actually the Prince, a singer with an upcoming performance. Taking on part-time work, Cinderalla saves for her ticket, although she goes to buy it, she finds herself rejected because only zombies are allowed to attend. Disappointed, she returns home and becomes intoxicated with her friends. The fairy transforms her into a zombie, and joyful, Cinderalla leaves to attend the performance. While making his appearance from the ceiling, the Prince accidentally falls onto Cinderalla, causing her to lose consciousness. She awakens in a bed with him beside her, and they make love. Realizing that dawn is approaching, when the spell will wear off, Cinderalla dresses and leaves him, although she loses her right eye when she trips.

While Cinderalla conceals the loss of her eye, the Prince announces his intention to marry the zombie woman whom the eye fits. The zombie women all pluck out one of their eyes, and Akko deceives the prince into believing that she is Cinderalla, although Cinderalla reveals Akko's deception with the help of Setsuko and the fairy, who now possesses all of her magical powers. Transformed into a zombie, Cinderalla marries the Prince. As Cinderalla concludes, Cinderalla has become successful with her giant fruits grown from yakitori sauce, and her husband does dinner shows at her father's remodeled restaurant. Now a celebrity, the fairy makes frequent television appearances, while Aki marries a reporter and Akko follows foreign idols. Cinderalla also buys a pancake-making machine for Caroline. Cinderalla also includes three short, related manga: "How Caroline Became a Glutton", which explores her backstory as a stripper; "Papa's Professional Cooking", which details a recipe for the fictitious sauce; and "Of Course We All Know", which focuses on the Prince's backstory in the form of lyrics.

Development

After the publication of her first major manga, the post-apocalyptic Pure Trance (1998), manga artist Junko Mizuno wrote and illustrated Cinderalla.[1] Doubting her ability to create a narrative, Mizuno's publishers at Koushinsya felt that a story with a basis in older material—such as European fairy tales, which saw popularity in Japan at the time[2]—would be preferable to an original one.[1] Mizuno was familiar with European fairy tales, which she read often as a child and found "very frightening."[2] Lacking a computer at the time, Mizuno was unable to color the manga herself; she expressed her unhappiness with the coloring done by Koushinsya's designer, whom she felt did not adhere to her wishes.[2] Mizuno continued her fairy tale adaptations with Hansel and Gretel and Princess Mermaid.[1]

Mizuno took an active role in adapting her fairy tales for an English-language audience.[2] Mizuno reversed the manga's original right-to-left art and subsequently redrew some pages.[1] Envisioning "the feel of a cheap American comic", she recolored the manga with "soft colors" and decided that it be printed on pulp paper, in contrast to the "too bright and white" Japanese edition.[2]

Release

Cinderalla did not appear as a serial in a magazine,[2] but was directly published as a bound volume in Japan by Koushinsya in February 2000.[3] It was licensed for an English-language translation in North America by Viz Media, who serialized the manga in its adult manga magazine Pulp: The Manga Magazine from the May 2001 issue to the July 2002 issue.[4][5] Viz Media then released a left-to-right volume of Cinderalla in July 2002.[5][6] Cinderalla has also been translated into French by Imho in 2004,[7] into Portuguese by Editora Conrad in 2006,[8] and into Spanish by Imho in 2008.[9]

Reception

The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales wrote that Cinderalla contained irony and dark humor, and its ending of Cinderalla's forgiveness of her stepsisters was reminiscent of the version written by Charles Perrault.[10] Fausto Salvadori of the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo described it as a sarcastic, bizarre and dark humor version of Cinderella that read like "an episode of The Powerpuff Girls written and directed by Coffin Joe".[8] The dark humor was also highlighted by Rebeca Fernández of the Spanish newspaper Público who described it as union of Hello Kitty and Chucky.[9]

References

- General

- Mizuno, Junko (2002). Junko Mizuno's Cinderalla. San Francisco: Viz Media. ISBN 978-1591160038. OCLC 51541535.

- Specific

- ^ a b c d Evers, Izumi; Junko Mizuno (2002). "Interview with Junko Mizuno". Cinderalla. San Francisco: Viz Media. pp. 130–35. ISBN 9781591160038. OCLC 51541535.

- ^ a b c d e f Gravett, Paul (2005). "Junko Mizuno: Queen Of The Cute & Creepy". Neo. Paul Gravett.com. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ "水野純子のシンデラーラちゃん" (in Japanese). Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Viz PR for May '01". Anime News Network. January 21, 2001. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ a b "Pulp Ends in August". Anime News Network. April 11, 2002. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Mizuno, Junko (2002). Junko Mizuno's Cinderalla. San Francisco: Viz Media. ISBN 978-1591160038. OCLC 51541535.

- ^ "Cinderalla (Mizuno, Junko) Imho" (in French). Manga News. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Salvadori, Fausto (July 28, 2006). "Versão em quadrinhos reconta Cinderela com humor negro". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Grupo Folha. Retrieved February 15, 2015 – via Universo Online.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fernández, Rebeca (November 2, 2008). "La princesa de los zombis". Público (in Spanish). Retrieved October 5, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Haase, Donald, ed. (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 633. OCLC 145554565.

External links

- Official website

- Cinderalla (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia