Civic, Australian Capital Territory

| Civic Canberra, Australian Capital Territory | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°16′55″S 149°07′43″E / 35.282°S 149.1286°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 4,835 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 3,220/km2 (8,350/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1927 | ||||||||||||||

| Gazetted | 20 September 1928 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2601 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 577 m (1,893 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 1.5 km2 (0.6 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| District | Canberra Central (North Canberra) | ||||||||||||||

| Territory electorate(s) | Kurrajong | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Canberra | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

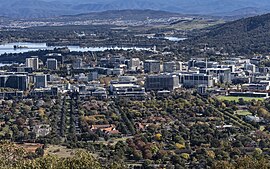

Civic is the city centre or central business district of Canberra. "Civic" is a common name for the district, but it is also called Civic Centre, City Centre, Canberra City and Canberra, and its official division name is City.[2]

Canberra's City was established in 1927, although the division name City was not gazetted until 20 September 1928. Walter Burley Griffin's design for Canberra included a "Civic Centre" with a separate "Market Centre" located at what is now Russell. However then Prime Minister Stanley Bruce vetoed this idea and only the Civic Centre was developed; the idea of the Market Centre was abandoned.

Overview

[edit]

Some of the earliest buildings constructed in Canberra were the Sydney and Melbourne buildings which flank Northbourne Avenue. The buildings house many shops, bars and restaurants.

The Canberra Centre, a three-storey shopping complex is Civic's main shopping precinct with a retail presence from the national chains David Jones, Myer and Big W department stores, as well as Coles and Aldi supermarkets, a Rebel sports store, several fashion outlets, and some eateries, among other businesses. Nearby is Glebe Park, a picturesque park near the centre of the city with elm trees and oaks from early European settlement before the city was founded. It has a children's play park. It is popular with people on their lunch breaks and younger children from the surrounding areas. Civic also is home to the Canberra Theatre, Casino Canberra, Canberra Museum and Gallery and the National Convention Centre.

Garema Place and City Walk are open areas of Civic for pedestrian traffic with many outdoor cafes. One of the longest running cafes in Civic was Gus's on Bunda Street.

City Interchange is used by ACTION and CDC Canberra bus services. It is located on East Row, Alinga Street, Mort Street and Northbourne Avenue. A light rail line terminates on Northbourne Avenue north of Alinga Street. On the western side of Northbourne Avenue (north of Alinga Street) is the Jolimont Centre, which is the terminal for Murrays services to Sydney, Wollongong and Batemans Bay and V/Line services to Albury and Bairnsdale.

Canberra City has relatively low height limits on buildings for the centre of a major city: the maximum height of buildings in Civic is 617 metres above sea level,[3] which is derived from the altitude of Parliament House. This height limit is equivalent to approximately 12 storeys for an office building or about 15 storeys for a residential building.

History

[edit]

Before the development of the City of Canberra, there was no clear commercial centre for the area, other than nearby Queanbeyan. Murray's store, considered the area's first retail store, operated from a house built in 1874 on the glebe of St John the Baptist Church, within the present boundaries of Commonwealth Park, to the east of what is now Nerang Pool. It burnt down in 1923.

Griffin's plan separated the national centre, the administrative centre of the city, now the Parliamentary Triangle, from the Civic Centre, the principal commercial area. The commercial centre was planned to be on what Griffin described as the Municipal Axis which was projected to run north-west from Mount Pleasant. Variations from Griffin's plan that affect City include the abandonment of a city railway and a reduction in the widths of some streets, including of London Circuit which was planned to be 200 feet (61 m) and was reduced to 100 feet (30 m). Griffin's civic focus on Vernon Knoll, now known as City Hill, has not materialised mainly because of the way city building has progressed.[4]

The first major buildings planned for the commercial centre were the Melbourne and Sydney Buildings, which were designed in the "Inter-War Mediterranean style".[5] Construction began in 1926[6] and they were finally completed in 1946. Immediately after World War II, the Melbourne and Sydney buildings still comprised the main part of Civic and the Blue Moon Cafe was the only place to go for a meal apart from the Hotel Canberra and the Hotel Civic.[7]

Up until the 1960s, Canberra shoppers found the retail environment frustrating. Many did their weekly shopping in Queanbeyan, where the central business district was more compact.[4] Major purchases were made in Sydney.[7] In 1963, the Monaro Mall (now Canberra Centre) opened. It included a branch of the David Jones department store.

Notable buildings and urban spaces

[edit]Sydney and Melbourne Buildings

[edit]

The Melbourne and Sydney buildings were based on design principles set by John Sulman in sketch form.[8] The design work was finalised by John Hunter Kirkpatrick. The buildings were the model which establish the colonnade principle, an important design element throughout Civic.[9] From 1921 to 1924 Sulman was chairman of the Federal Capital Advisory Committee, and in that role was involved in the planning of Canberra and refining Griffin's plan.

Sulman's concept of arcaded loggias was derived from Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital) and the cloisters of the 15th century Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze. The Mediterranean influence was maintained by Kirkpatrick with Roman roof tiles and cast embellishments such as roundels. The buildings were originally constructed with open first floor verandahs which have since largely been glazed in.

The Melbourne Building was sold sequentially as independent parcels from 1927 until 1946. The corner of West Row and London Circuit was built specifically for the Bank of New South Wales. The manager lived above the bank. Much of the Melbourne Building facing West Row was completed by the Commonwealth Government in 1946 and used as the location of the Commonwealth Employment Service. From 1944 to 1953, the Canberra University College was housed in the Melbourne building. On 11 April 1953 the Melbourne Building was severely damaged by fire,[10] and the college relocated (it eventually became the Australian National University).

In 2002 a fire extensively damaged Mooseheads bar,[11] resulting in a partial roof collapse. On 17 February 2014, the Sydney Building was significantly damaged by a fire which began with an explosion in a ground floor Japanese restaurant adjacent to East Row around 9.45 am.[12] The fire was quickly brought under control, but was not extinguished until 2 am, more than 14 hours later. During the blaze, a section of the heritage listed building's roof collapsed. The fire saw the evacuation of 40 businesses as well as closures of several roads and the City Bus Station, causing bus route diversions and major disruption to ACTION public transport services.[13]

Hotel Civic

[edit]

The Hotel Civic opened in 1935. It was constructed in an Art Deco style from Canberra Cream bricks. It was demolished in late 1984 through early 1985.[14] The hotel was on the corner of Alinga Street and the eastern side of Northbourne Avenue.

In 1965, the Hotel Civic was the scene of a protest about the segregation of women in the hotel:

... a protest where a number of us [including the interviewee Helen Jarvis] chained ourselves to the bar in the Hotel Civic. Women weren't allowed to be served in the public bar -- that was the law in both NSW and the ACT. We had to use the saloon bar or the ladies' bar, where prices were higher, or to huddle out the back around the old kegs. They were also morose places, at least at the Civic, which was the only pub near the university. The public bar had all the spirit. We chained ourselves to the public bar. The bartender wouldn't serve us, but there were some sympathetic men who bought drinks for us. The newspapers trivialized it, of course: they wrote it up with the headline, "Women breast the bar".[15]

Civic Square

[edit]

Civic Square houses the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly, Canberra Museum and Gallery, Civic Library and Canberra Theatre as well as many local cultural organizations, including the Canberra division of the National Trust of Australia.

Civic Square was designed by Yuncken Freeman architects and completed in 1961. Civic Square is sited within a primary axis of Griffin's design for Canberra which links City Hill and Mount Ainslie. Griffin intended that the square be the 'heart of the city'. Civic Square was listed on the register of the former National Estate.[16]

The Canberra Theatre was opened in June 1965 with the Australian Ballet's production of Swan Lake. The old Playhouse, also from 1965, was demolished and rebuilt in 1998. The link between the Theatre and Playhouse buildings has been redeveloped to include the Civic Library and the theatre's bar and administration area.

A sculpture of Ethos by Tom Bass was commissioned by the National Capital Development Commission in 1959 and unveiled in 1961. "The NCDC intended that the work would emphasize that Canberra is the non-political centre, the locale of commerce and of private enterprise in its best sense." The sculpture was designed to represent the spirit of the community. Bass interpreted this in the figure which he intended "the love which Canberra people have for their city to be identified with her...I want them to be conscious of her first as an image from a distance...then comes the moment when they become personally involved with her... they feel her looking at them, reflecting their love for the place".

According to the draft heritage listing, "The form of the work is highly symbolic. The figure is robed in a fabric richly embossed with emblems and figures representing the Community. The shallow saucer on which the figure stands represents Canberra's nick-name "Frosty Hollow". The saucer is 6 sided because the plan for Civic square is itself hexagonal. The surface of the saucer bears a relief map of Canberra and the rolling countryside around it. At the feet of Ethos are indentations that represent the lake that was later to fill the space between the Civic Centre and the administrative part of the city. The bursting sun she holds aloft is symbolic of culture and enlightenment which the presence of Canberra's University, its research organisations and the Diplomatic Corps and so on give to the city". Bass regarded the work as his most important civic work. During the 1960s and 70s, pictures of the sculpture were frequently used in Canberra tourism images.[17]

Canberra Olympic Pool

[edit]Construction for a new public pool started in October 1953 and the Canberra Olympic Pool was opened on 22 December 1955, right at the peak of national interest in competitive and recreational swimming leading up to the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne. The new pool complex included three pools; a blue-tiled seven lane pool; a 60 by 90 foot diving pool with a cantilevered reinforced concrete diving tower complete with 3m, 5m and 10m diving platforms, and six springboards; and a children's pool. Other facilities included a refreshment kiosk, dressing sheds, private change booths and 800 lockers. The pool complex, gardens and overall design were described "A feature of the new centre is its spaciousness. Garden plots and lawns covered with gay beach umbrellas surround the pools and a strikingly modern colour scheme, with deep blue predominating, on all exterior walls make an attractive setting".[18] The pool was designed in 1953 by Ian Slater, architect from the Commonwealth Department of Works, and was awarded a Sulman Medal by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.[19]

Canberra Centre

[edit]

Civic's major shopping mall is the Canberra Centre. Opened as the Monaro Mall in 1963, it was the first Australian three-storey, fully enclosed and air conditioned shopping centre. It was opened by the Prime Minister Robert Menzies.[20] In 1989 it was substantially redeveloped and renamed the Canberra Centre. A further redevelopment was completed by late 2007, substantially adding to the diversity of retailers and services within it including a Dendy Cinema complex.

Heritage listings

[edit]Civic has a number of heritage-listed buildings including:

- 20-22 London Circuit: Reserve Bank of Australia Building[21]

Crime

[edit]Canberra City is Canberra's largest nightclub district and experiences high levels of alcohol-related violence.[22] More than 600 assaults occurred in the city between December 2010 and December 2013, four times more than the next worst suburb in Canberra of Belconnen.[22]

Demographics

[edit]

At the 2021 census, the population of Canberra City was 4,835, including 50 (1.0%) Indigenous persons and 2,155 (44.6%) Australian-born persons. 99.6% of dwellings were flats, units or apartments (Australian average: 14.2%), while none were semi-detached, row or terrace houses (Australian average: 12.6%) or separate houses (compared to the Australian average of 72.3%).[1]

In 2021, 41.3% of the population were professionals, compared to the Australian average of 24.0%. Notably 16.4% worked in central government administration, compared to the Australian average of 1.1%, although the ACT-wide average is a similar 17.1%. 55.0% of the population had no religion (compared to the ACT average of 43.5% and the Australian average of 38.4%), while 13.2% did not state their religion, 9.7% were Catholic, 3.9% Anglican and 3.6% Buddhist. 16.2% of the population was born in China, 3.5% in India, 2.3% in England, 1.7% in Malaysia and 1.7% in South Korea. 50.8% of people spoke only English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Mandarin 17.3%, and Cantonese 2.6%.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "City (SSC)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Search for street and suburb names: City". Environment and Planning Directorate. ACT Government. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ "City Precinct Map and Code" (PDF). ACT Environment and Sustainable Development. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b King, H. W (1954). "Factors of Site and Plan". In White, H. L. (ed.). Canberra: A Nation's Capital. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 209–220.

- ^ Philip Leeson Architects Pty Ltd (15 August 2017). "Northbourne Plaza Project: Statement of Heritage Effects" (PDF). p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Building of Civic Centre". The Canberra Times. 10 September 1926. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ a b Green, Stephanie. "Gorman House history". Gorman House Arts Centre. Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ Warden, Ian (17 February 2014). "History of the Sydney Building". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

- ^ "20032. Melbourne and Sydney Buildings" (PDF). Entry to the ACT Heritage Register; Heritage Act 2004. ACT Heritage Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ Warden, Ian (19 February 2014). "No shortage of help in fighting the great fire of 1953". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

- ^ Jean, David (12 April 2011). "Best to steer clear of 'out-of-control' ADFA boys". The Advertiser. Adelaide.

- ^ Rickard, Lucy; Westcott, Ben; Raggatt, Matthew (17 February 2014). "Fire at Sydney Building in Civic". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ McIlroy, Tom (18 February 2014). "Civic chaos continues as Sydney Building fire investigated". The Canberra Times.

- ^ "60 tonne capacity excavator demolishes the Hotel Civic; photograph taken 30 January 1985". Image Library. ACT Heritage Library. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ Cheng, Eva. "Vietnam and the women's liberation movement". Green Left Weekly. Archived from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ "Civic Square Complex, London Cct, Canberra, ACT, Australia". Department of the Environment. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "10007. Ethos statue" (PDF). Entry to the ACT Heritage Register; Heritage Act 2004. ACT Heritage Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ "Olympic Pool To Open To-morrow". The Canberra Times. 21 December 1955. p. 2. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Martin, Eric (9 March 2023). "AIA ACT Chapter: Register of Significant Architecture—Citation Canberra Olympic Pool" (PDF). Architecture.com.au. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Menzies, Robert (5 March 1963). Opening of the Monaro Shopping Mall (Speech). Canberra. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Reserve Bank of Australia (Place ID 105396)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ a b Knaus, Christopher (2 December 2013). "Special series - Punch Drunk, part one: Civic remains a hotbed of alcohol-fuelled violence". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013.