Coconut crab

| Coconut crab | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Infraorder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Birgus

|

| Species: | B. latro

|

| Binomial name | |

| Birgus latro Linnaeus, 1767

| |

| |

| Coconut crab distribution | |

The coconut crab (Birgus latro) is the largest terrestrial arthropod in the world. It is a derived hermit crab which is known for its ability to crack coconuts with its strong pincers in order to eat the contents. It is sometimes called the robber crab or palm thief (in German, Palmendieb), because some coconut crabs are rumored to steal shiny items such as pots and silverware from houses and tents. Another name is the terrestrial hermit crab, due to the use of shells by the young animals (although terrestrial hermit crab also applies to a number of other hermit crabs — see Australian land hermit crab). The coconut crab also has different local names as for example ayuyu in Guam, or unga or kaveu.

Physical description

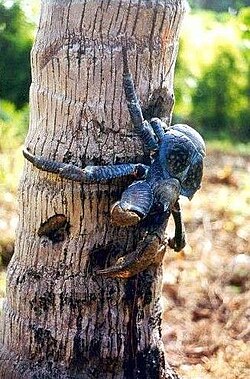

Reports about the size of Birgus latro vary, and most references give a weight of up to 4 kg (9 lb), a body length of up to 400 mm (16 in), and a leg span of 1 m (3 ft), with males generally being larger than females. Some reports claim weights up to 17 kg and a body length of 1 m. It is believed that this is near the theoretical limit for a terrestrial arthropod. However, when the body is supported by water, larger sizes are possible (see Japanese spider crab). They can reach an age of up to 30–60 years (references vary). The body of the coconut crab is, like all decapods, divided into a front section (cephalothorax) and an abdomen, which has 10 legs. The front-most legs have massive claws used to open coconuts, and these claws (chelae) can lift objects up to 29 kg (64 lb) in weight. The next three pairs have smaller tweezer-like chelae at the end, and are used as walking limbs. In addition these specially adapted limbs enable the coconut crab to climb vertically up trees (often coconut palms) up to 6 m high. The last pair of legs is very small and serves only to clean the breathing organs. These legs are usually held inside the carapace, in the cavity containing the breathing organs.

Although Birgus latro is a derived type of hermit crab, only the juveniles use salvaged snail shells to protect their soft abdomens, and adolescents sometimes use broken coconut shells to protect their abdomens. Unlike other hermit crabs, the adult coconut crabs do not carry shells, but instead harden their abdominal armor by depositing chitin and chalk. They also bend their tails underneath their bodies for protection, as do most true crabs. The hardened abdomen protects the coconut crab and reduces water loss on land, but has to be moulted at periodic intervals. Moulting takes about 30 days, during which the animal's body is soft and vulnerable, and it stays hidden for protection.

Coconut crabs cannot swim and will drown in water. They use a special organ called a branchiostegal lung to breathe. This organ can be interpreted as a developmental stage between gills and lungs, and is one of the most significant adaptations of the coconut crab to its habitat. The chambers of this breathing organ are located in the rear of the cephalothorax. They contain a tissue similar to that found in gills, but suited to the absorption of oxygen from air, rather than water. They use their last, smallest pair of legs to clean these breathing organs, and to moisten them with seawater. The organs require water to function, and the crab provides this by stroking its wetted legs over the spongy tissues nearby. Coconut crabs may also drink salt water, using the same technique to transfer water to their mouths.

In addition to this breathing organ, the coconut crab has an additional rudimentary set of gills. However, while these gills were probably used to breathe under water in the evolutionary history of the species, they no longer provide sufficient oxygen, and an immersed coconut crab will drown within a few hours or minutes (reports vary, probably depending on the levels of stress and exercise and the resulting oxygen consumption).

Another distinctive organ of the coconut crab is its nose. The process of smelling works very differently depending whether the smelled molecules are hydrophilic molecules in water or hydrophobic molecules in air. As most crabs live in the water, they have specialized organs called aesthetascs on their antennae to determine both the concentration and the direction of a smell. However, as coconut crabs live on the land, the aesthetascs on their antennae differ significantly from those of other crabs and look more like the smelling organs of insects, called sensilia. While insects and the coconut crab originate from different evolutionary paths, the same need to detect smells in the air led to the development of remarkably similar organs, making it an example of convergent evolution. Coconut crabs also flick their antennae as insects do to enhance their reception. They have an excellent sense of smell and can detect interesting odors over large distances. The smell of rotting meat, bananas and coconuts catch their attention especially, as potential food sources.

Reproduction

Coconut crabs mate frequently and quickly on dry land in the period from May to September, especially in July and August. The male and the female fight with each other, and the male turns the female on her back to mate. The whole mating procedure takes about 15 minutes. Shortly thereafter, the female lays her eggs and glues them to the underside of her abdomen, carrying the fertilized eggs underneath her body for a few months. At the time of hatching, usually October or November, the female coconut crab releases the eggs into the ocean at high tide. These larvae are called zoeas. It is reported that all coconut crabs do this on the same night, with many females on the beach at the same time.

The larvae float in the ocean for 28 days, during which a large number of them are eaten by predators. Afterwards, they live on the ocean floor and on the shore as hermit crabs, using discarded shells for protection for another 28 days. At that time, they sometimes visit dry land. As with all hermit crabs, they change their shells as they grow. After these 28 days, they leave the ocean permanently and lose the ability to breathe in water. Young coconut crabs that cannot find a seashell of the right size also often use broken coconut pieces. When they outgrow even coconut shells, they develop a hardened abdomen. About 4 to 8 years after hatching the coconut crab matures and can reproduce. This is an unusually long development period for a crustacean.

Diet

The diet of coconut crabs consists primarily of fruit, including coconuts and figs. However, they will eat nearly anything organic, including leaves, rotten fruit, tortoise eggs, dead animals, and the shells of other animals, which are believed to provide calcium. They may also eat live animals that are too slow to escape, such as freshly hatched sea turtles. Coconut crabs often try to steal food from each other and will pull their food into their burrows to be safe while eating.

The coconut crab climbs trees to eat coconuts or fruit, to escape the heat or to escape predators. Some people believe that the coconut crab cuts the coconuts from the tree to eat them on the ground (hence the German name palm thief and the Dutch Klapperdief). However, according to the late German biologist Holger Rumpf (sometimes spelled Rumpff) the animal is not intelligent enough for such a planned action, and rather accidentally drops a coconut while attempting to open it on the tree. Coconut crabs cut holes into coconuts with their strong claws and eat the contents; this behavior is unique in the animal kingdom.

It was doubted for a long time that the coconut crab could open coconuts, and in experiments, some have starved to death surrounded by coconuts. However, in the 1980s Rumpf was able to observe and study them opening coconuts in the wild. The crab has developed a special technique to do so: if the coconut is still covered with husk, it will use its claws to rip off strips, always starting from the side with the three germination pores, the group of three small circles found on the outside of the coconut. Once the pores are visible, the crab will bang its pincers on one of them until they break. Afterwards, it will turn around and use the smaller pincers on its other legs to pull out the white flesh of the coconut. Using their strong claws, larger individuals can even break the hard coconut into smaller pieces for easier consumption.

Habitat

Coconut crabs live alone in underground burrows and rock crevices, depending on the local terrain. They dig their own burrows in sand or loose soil. During the day, the animal stays hidden, to protect itself from predators and reduce water loss from heat. While resting in its burrow, the coconut crab closes the entrance with one of its claws to create the moist microclimate within the burrow necessary for its breathing organs. In areas with a large coconut crab population, some may also come out during the day, perhaps to gain an advantage in the search for food. Coconut crabs will also sometimes come out during the day if it is moist or raining, since these conditions allow them to breathe more easily. They live almost exclusively on land, and some have been found up to 6 km from the ocean.

Distribution

Coconut crabs live in areas throughout the Indian and western Pacific oceans. Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean has the largest and best-preserved population in the world. Large populations also exist on the Cook Islands (Pacific Islands), especially Pukapuka, Suwarrow, Mangaia, Takutea, Mauke, Atiu and smaller islands of Palmerston. Other populations exist on the Seychelles, especially Aldabra, Glorioso Islands, Astove Island, Assumption Island, and Cosmoledo, but the coconut crab is extinct on the central islands. They are also known on several of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. There is some difference in colour between the animals found on different islands, ranging from light violet through deep purple to brown.

As they cannot swim as adults, coconut crabs over time must have colonized the islands as larvae, which can swim. However, due to the large distances between the islands, some researchers believe a larvae stadium of 28 days is not enough to travel the distance and they assume juvenile coconut crabs reached other islands on driftwood and flotsam.

The distribution shows some gaps, as for example around Borneo, Indonesia or New Guinea. These islands were within easy reach of the crab, and also have a suitable habitat, yet have no coconut crab population. This is due to the coconut crabs being eaten to extinction by people. However, coconut crabs are known to live on the islands of the Wakatobi Marine National Park in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Conservation status

According to the IUCN Red List criteria, there is not enough data to decide if the coconut crab is an endangered species, and therefore it is listed as DD (data deficient)[2]. However, according to some reports the populations are quite large, with one of the largest populations being on Caroline Island. It is believed that the coconut crab is quite common on some islands, but rather rare on others. Coastal development on many islands reduces the natural habitat of the crab.

The juvenile coconut crab is vulnerable to introduced carnivores such as rats, pigs, or ants such as the yellow crazy ant. Adult coconut crabs have no natural predators, and are eaten only by people. The adults have poor eyesight, and detect enemies based on ground vibration.

Overall, it seems that large human populations have a negative effect on the coconut crab population, and in some areas, populations are reported to be declining due to over-harvesting. The coconut crab is protected in some areas, with minimum sizes for taking and a protected breeding period.

Cultural aspects

This hermit crab with its intimidating size and strength has a special position in the culture of the islanders. The coconut crab is eaten by the Pacific islanders, and is considered a delicacy and an aphrodisiac, with a taste similar to lobster and crabmeat. The most prized parts are the eggs inside the female coconut crab and the fat in the abdomen. Coconut crabs can be cooked in a similar way to lobsters, by boiling or steaming. Different islands also have a variety of recipes, as for example coconut crab cooked in coconut milk.

While the coconut crab itself is not poisonous, it may become poisonous depending on its diet, and cases of coconut crab poisoning have occurred. It is believed that the poison comes from plant toxins, which would explain why some animals are poisonous and others not. It may also be possible that this poison is considered an aphrodisiac, similar to the highly poisonous pufferfish eaten in Japan. However, coconut crabs are not a commercial product and are usually not sold.

Hunting is best on a moonless night with wet ground using flashlights. The best time is the three days following the new moon. Coconut crabs can also be hunted during the day, but this involves digging to reach them in their burrows or a fire to smoke them out of their hiding places. It is also suggested that spreading burnt coconut halves will attract coconut crabs.

Children sometimes play (carefully) with coconut crabs. One technique is to trick them by placing some wet grass at an angle on a palm tree that contains a coconut crab. When the animal climbs down, it believes the grass is the ground and releases its grip on the tree, and subsequently falls.

The coconut crab is admired for its strength, and it is said that villagers use this animal to guard their coconut plantations. A coconut crab may attack a person if it is threatened. The coconut crab, especially if it is not yet fully grown, is also sold as a pet, for example in Tokyo. The cage must be strong enough that the animal cannot use its strong claws to escape.

Notes

References

- Altevogt, R., Davis., T.A. (1975) Birgus latro: India's monstrous crab. A study and an appeal. Bulletin of the Department of Marine Sciences, University of Cochin.

- Grubb, P. (1971) Ecology of terrestrial decapod crustaceans on Aldabra. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences. 260: 411-416.

- Held, E.E. (1963) Moulting behaviour of Birgus latro. Nature, 200: 799-800.

- Barnett, L.K., Emms, C. and Clarke, D. (1999). The coconut or robber crab (Birgus latro) in the Chagos Archipelago and its captive culture at London Zoo, pp. 273-284: in Sheppard, C.R.C. and Seaward, M.R.D. (Eds). Ecology of the Chagos Archipelago. Linnean Society Occasional Publications, 2. Westbury Publishing. pp. 351.

- Lavery S Moritz C & Fielder DR (1996) Indo-Pacific population structure and evolutionary history of the Coconut Crab Birgus latro. Mol Ecol 5: 557-570.

- Combs, C. A. N., Alford, A., Boynton, M. and Henry, R. P (1992). Behavioural regulation of haemolymph osmolarity through selective drinking in land crabs, Birgus latro and Gecarcoidea lalandii. Biol. Bull. 182, 416-.

- Greenaway, P. and Morris, S (1989). Adaptations to a terrestrial existence by the robber crab Birgus latro. III. Nitrogenous excretion. J. Exp. Biol. 143: 333-.

- Greenaway, P., Taylor, H. H. and Morris, S (1990). Adaptations to a terrestrial existence by the robber crab Birgus latro. VI. The role of the excretory system in fluid balance. J. Exp. Biol. 152: 505-.

- Morris, S., Taylor, H. H. and Greenaway, P (1991). Adaptations to a terrestrial existence in the robber crab Birgus latro L. VII. The branchial chamber and its role in urine reprocessing. J. Exp. Biol. 161: 315-.

- Taylor, H. H., Greenaway, P. and Morris, S (1993). Adaptations to a terrestrial existence in the robber crab Birgus latro L. VIII. Osmotic and ionic regulation on freshwater and saline drinking regimens. J. Exp. Biol. 179: 93-113 (PDF download)

- Stensmyr, M. C., Erland S., Hallberg E., Wallén R., Greenaway P.,Hansson B. S. (2005). Insect-Like Olfactory Adaptations in the Terrestrial Giant Robber Crab. Current Biology 15: 116-121.

External links

- ARKive - images and movies of the coconut crab (Birgus latro)

- The Crab Street Journal

- The Coconut Crab (Birgus latro): A Comprehensive Account Of The Biology And Conservation Issues