Automotive battery

An automotive battery, or car battery, is a rechargeable battery that is used to start a motor vehicle.

Its main purpose is to provide an electric current to the electric-powered starting motor, which in turn starts the chemically-powered internal combustion engine that actually propels the vehicle. Once the engine is running, power for the car's electrical systems is still supplied by the battery, with the alternator charging the battery as demands increase or decrease.

Battery in modern cars

[edit]Gasoline and diesel engine

[edit]Typically, starting uses less than three percent of the battery capacity. For this reason, automotive batteries are designed to deliver maximum current for a short period of time. They are sometimes referred to as "SLI batteries" for this reason, for starting, lighting and ignition. SLI batteries are not designed for deep discharging, and a full discharge can reduce the battery's lifespan.[1][2]

As well as starting the engine, an SLI battery supplies the extra power necessary when the vehicle's electrical requirements exceed the supply from the charging system. It is also a stabilizer, evening out potentially damaging voltage spikes.[3] While the engine is running most of the power is provided by the alternator, which includes a voltage regulator to keep the output between 13.5 and 14.5 V.[4] Modern SLI batteries are lead-acid type, using six series-connected cells to provide a nominal 12-volt system (in most passenger vehicles and light trucks), or twelve cells for a 24-volt system in heavy trucks or earth-moving equipment, for example.[5]

Gas explosions can occur at the negative electrode where hydrogen gas can build up due to blocked battery vents or a poorly ventilated setting, combined with an ignition source.[6] Explosions during engine start-up are typically associated with corroded or dirty battery posts.[6] A 1993 study by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration said that 31% of vehicle battery explosion injuries occurred while charging the battery.[7] The next-most common scenarios were while working on cable connections, while jump-starting, typically by failing to connect to the dead battery before the charging source and failing to connect to the vehicle chassis rather than directly to the grounded battery post, and while checking fluid levels.[6][7] Close to two-thirds of those injured suffered chemical burns, and nearly three-fourths suffered eye injuries, among other possible injuries.[7]

Electric and hybrid cars

[edit]Electric vehicles (EVs) are powered by a high-voltage electric vehicle battery, but they usually have an automotive battery as well, so that they can use standard automotive accessories which are designed to run on 12 V. They are often referred to as auxiliary batteries.

Unlike conventional, internal combustion engined vehicles, EVs don't charge the auxiliary battery with an alternator—instead, they use a DC-to-DC converter to step down the high voltage to the required float-charge voltage (typically around 14 V).[8]

Further, an electric vehicle does not have a starter motor, thus needs only a limited amount of power and energy from its auxiliary battery. As such, Tesla introduced in 2021 a lithium-ion auxiliary battery storing only 99 Wh of energy.[9]

History

[edit]Early cars did not have batteries, as their electrical systems were limited. Electric power for the ignition was provided by a magneto, the engine was started with a crank, headlights were gas-powered and a bell or bulb-horn was used instead of an electric horn. Car batteries became widely used around 1920 as cars became equipped with electric starter motors.[10]

The first starting and charging systems were designed to be 6-volt and positive-ground systems, with the vehicle's chassis directly connected to the positive battery terminal.[11] Today, almost all road vehicles have a negative ground system.[12] The negative battery terminal is connected to the car's chassis.

The Hudson Motor Car Company was the first to use a standardized battery in 1918 when they started using Battery Council International batteries. BCI is the organization that sets the dimensional standards for batteries.[13]

Cars used 6 V electrical systems and batteries until the mid-1950s. The changeover from 6 to 12 V happened when bigger engines with higher compression ratios required more electrical power to start.[14] Smaller cars, which required less power to start stayed with 6 V longer, for example the Volkswagen Beetle in the mid-1960s and the Citroën 2CV in 1970.

The AGM sealed battery (for automobiles), which did not require refilling, was invented in 1971.[10]

In the 1990s a 42V electrical system standard was proposed. It was intended to allow more powerful electrically driven accessories, and lighter automobile wiring harnesses. However, the availability of higher-efficiency motors, new wiring techniques, and digital controls, and a focus on hybrid vehicle systems that use high-voltage starter/generators have largely eliminated the push for switching the main automotive voltages.[15]

In 2023 Tesla started deliveries of their Cybertruck that uses a 48-volt electrical system, reducing 70% of the wiring in the vehicle.[16]

Design

[edit]An automobile battery is an example of a wet cell battery, with six cells. Each cell of a lead storage battery consists of alternate plates made of a lead alloy grid filled with sponge lead plates (cathode)[17] or coated with lead dioxide (anode).[17] Each cell is filled with a sulfuric acid solution, which is the electrolyte. Initially, cells each had a filler cap, through which the electrolyte level could be viewed and which allowed water to be added to the cell. The filler cap had a small vent hole which allowed hydrogen gas generated during charging to escape from the cell.

The cells are connected by short heavy straps from the positive plates of one cell to the negative plates of the adjacent cell. A pair of heavy terminals, plated with lead to resist corrosion, are mounted at the top, sometimes the side, of the battery. Early auto batteries used hard rubber cases and wooden plate separators. Modern units use plastic cases and woven sheets to prevent the plates of a cell from touching and short-circuiting.

In the past, auto batteries required regular inspection and maintenance to replace water that was decomposed during the operation of the battery. "Low-maintenance" (sometimes called "zero-maintenance") batteries use a different alloy for the plate elements, reducing the amount of water decomposed on charging. A modern battery may not require additional water over its useful life; some types eliminate the individual filler caps for each cell. A weakness of these batteries is that they are very intolerant of deep discharge, such as when the car battery is completely drained by leaving the lights on. This coats the lead plate electrodes with lead sulfate deposits and can reduce the battery's lifespan by a third or more.

VRLA batteries, also known as absorbed glass mat (AGM) batteries are more tolerant of deep discharge but are more expensive.[18] VRLA batteries do not permit addition of water to the cell. The cells each have an automatic pressure release valve, to protect the case from rupture on severe overcharge or internal failure. A VRLA battery cannot spill its electrolyte which makes it particularly useful in vehicles such as motorcycles.

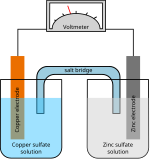

Batteries are typically made of six galvanic cells in a series circuits. Each cell provides 2.1 volts for a total of 12.6 volts at full charge.[19] During discharge, at the negative (lead) terminal a chemical reaction releases electrons to the external circuit, and at the positive (lead oxide) terminal another chemical reaction absorbs electrons from the external circuit. This drives the electrons through the external circuit wire (an electrical conductor) to produce an electric current (electricity). As the battery discharges, the acid of the electrolyte reacts with the materials of the plates, changing their surface to lead sulfate. When the battery is recharged, the chemical reaction is reversed: the lead sulfate reforms into lead dioxide. With the plates restored to their original condition, the process may be repeated.

Some vehicles use other starter batteries. For weight savings, the 2010 Porsche 911 GT3 RS has a lithium-ion battery as an option;[20] from 2018 onward, all Kia Niro conventional hybrids feature one as well.[21] Heavy vehicles may have two batteries in series for a 24 V system or may have series-parallel groups of batteries supplying 24 V.[22]

Specifications

[edit]Physical format

[edit]Batteries are grouped by physical size, type and placement of the terminals, and mounting style.[18]

Amp hours (Ah)

[edit]Ampere hours (Ah or A·h) is a unit related to the energy storage capacity of the battery. This rating is required by law in Europe.

The ampere hour rating is generally defined as the product of (the current a battery can provide for 20 hours at a constant rate, at 80 degrees F (26.6 °C), while the voltage drops to a cut-off of 10.5 volts) times 20 hours. In theory, at 80 degrees F, a 100 Ah battery should be able to continuously provide 5 amps for 20 hours while maintaining a voltage of at least 10.5 volts. The relationship between the Ah capacity and the discharge rate is not linear; as the discharge rate is increased, the capacity decreases. A battery with a 100 Ah rating generally will not be able to maintain a voltage above 10.5 volts for 10 hours while being discharged at constant rate of 10 amps. Capacity also decreases with temperature.

Cranking amperages (CCA, CA, MCA, HCA)

[edit]- Cold cranking amperes (CCA): the amount of current a battery can provide at 0 °F (−18 °C) for 30 seconds while maintaining a voltage of at least 7.2 volts. Modern cars with computer-controlled fuel-injected engines take no more than a few seconds to start and CCA figures are less important than they used to be.[23] It is important not to confuse CCA with CA/MCA or HCA numbers as the latter will always be higher due to warmer temperatures. For example, a 250 CCA battery will have more starting power than a 250 CA (or MCA) one, and likewise a 250 CA will have more than a 250 HCA one.[24]

- Cranking amperes (CA): the amount of current a battery can provide at 32 °F (0 °C), again for 30 seconds at a voltage equal to, or greater than, 7.2 volts.

- Marine cranking amperes (MCA): like CA, the amount of current a battery can provide at 32 °F (0 °C), and often found on batteries for boats (hence "marine") and lawn garden tractors which are less likely to be operated in conditions where ice can form.[25]

- Hot cranking amperes (HCA) is the amount of current a battery can provide at 80 °F (27 °C). The rating is defined as the current a lead-acid battery at that temperature can deliver for 30 seconds and maintain at least 1.2 volts per cell (7.2 volts for a 12-volt battery).

Group size

[edit]Battery Council International (BCI) group size specifies a battery's physical dimensions, such as length, width, and height. These groups are determined by the organization.[26][27]

Date codes

[edit]- In the United States there are codes on batteries that indicate when they were manufactured. When batteries are stored, they start losing their charge; this is due to non-current-producing chemical reactions of the electrodes with the battery acid. A battery made in October 2015 will have a numeric code of 10-5 or an alphanumeric code of K-5. "A" is for January, "B" is for February, and so on (the letter "I" is skipped).[23]

- In South Africa the code on a battery to indicate production date is part of the casing and cast into the bottom left of the cover. The code is year and week number (YYWW), e.g. 1336 is for week 36 in the year 2013.

Use and maintenance

[edit]Excess heat is a main cause of battery failures, as when the electrolyte evaporates due to high temperatures, decreasing the effective surface area of the plates exposed to the electrolyte, and leading to sulfation. Grid corrosion rates increase with temperature.[28][29] Also low temperatures can lead to battery failure.[30]

If the battery is discharged to the point where it can't start the engine, the engine can be jump started via an external source of power. Once running, the engine can recharge the battery, if the alternator and charging system are undamaged.[31]

Corrosion at the battery terminals can prevent a car from starting due to electrical resistance, which can be prevented by the proper application of dielectric grease.[32][33]

Sulfation is when the electrodes become coated with a hard layer of lead sulfate, which weakens the battery. Sulfation can happen when battery is not fully charged and remains discharged.[34] Sulfated batteries should be charged slowly to prevent damage.[35]

SLI batteries (starting, lighting, and ignition) are not designed for deep discharge, and their life is reduced when subjected to this.[36]

Starting batteries have plates designed for increased surface area and thus high instant current capability, whereas marine (hybrid) and deep cycle types will have thicker plates and more room at the bottom of the plates for spent plate material to gather before shorting the cell.

Car batteries using lead-antimony plates require regular topping-up with pure water to replace water lost due to electrolysis and evaporation. By changing the alloying element to calcium, more recent designs have reduced the rate of water loss. Modern car batteries have reduced maintenance requirements, and may not provide caps for addition of water to the cells. Such batteries include extra electrolyte above the plates to allow for losses during the battery life.

Some battery manufacturers include a built-in hydrometer to show the state of charge of the battery.[dubious – discuss][clarification needed]

The primary wear-out mechanism is the shedding of active material from the battery plates, which accumulates at the bottom of the cells and which may eventually short-circuit the plates. This can be substantially reduced by enclosing one set of plates in plastic separator bags, made from a permeable material. This allows the electrolyte and ions to pass through but keeps the sludge build up from bridging the plates. The sludge largely consists of lead sulfate, which is produced at both electrodes.

Environmental impact

[edit]Battery recycling of automotive batteries reduces the need for resources required for the manufacture of new batteries, diverts toxic lead from landfills, and prevents the risk of improper disposal. Once a lead–acid battery ceases to hold a charge, it is deemed a used lead-acid battery (ULAB), which is classified as hazardous waste under the Basel Convention. The 12-volt car battery is the most recycled product in the world, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency. In the U.S. alone, about 100 million auto batteries a year are replaced, and 99 percent of them are turned in for recycling.[37] However, the recycling may be done incorrectly in unregulated environments. As part of global waste trade, ULABs are shipped from industrialized countries to developing countries for disassembly and recuperation of the contents. About 97 percent of the lead can be recovered. Pure Earth estimates that over 12 million people in developing countries are affected by lead contamination from ULAB processing.[38]

See also

[edit]- Anderson Powerpole connectors

- Automobile auxiliary power outlet ("cigarette lighter receptacle")

- Battery charger

- Battery tester

- Deep-cycle battery

- Lead–acid battery

- List of auto parts

- VRLA battery (AGM and gel cell)

- Peukert's law

- 48-volt electrical system

References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, Larry. "Battery Tutorial". chargingchargers.com. Charging Chargers. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- ^ Pradhan, S. K.; Chakraborty, B. (2022-07-01). "Battery management strategies: An essential review for battery state of health monitoring techniques". Journal of Energy Storage. 51: 104427. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.104427. ISSN 2352-152X.

- ^ "What is a lead battery?". batterycouncil.org. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "Automotive Charging Systems – A Short Course on How They Work".

- ^ "Q & A: Car Batteries". van.physics.illinois.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ a b c Vartabedian, Ralph (August 26, 1999), "How to Avoid Battery Explosions (Yes, They Really Happen)", Los Angeles Times

- ^ a b c Injuries Associated With Hazards Involving Motor Vehicle Batteries, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, July 1997

- ^ Herron, David. "Why is there a 12 volt lead-acid battery, and how is it charged in an electric car?". greentransportation.info. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Kane, Mark (2021-11-07). "Tesla's New 12V Li-Ion Auxiliary Battery Has CATL Cells Inside". insideevs.com. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ a b "History of the car battery". racshop.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "Positive Vs. Negative Ground - Will charger work on positive ground vehicles?". Archived from the original on 2020-07-27.

- ^ "Why POSITIVE EARTH?". MGAguru.com. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ "6-Volt Batteries". hemmings.com. July 2006. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "6 Volt to 12 Volt Changeover". fillingstation.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-02. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "Whatever Happened to the 42-Volt Car?". Popular Mechanics. 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ Akhtar, Riz (December 1, 2023). ""Whole new step-change in technology:" Cybertruck starts at $US61,000". The Driven. Australia. Retrieved December 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Le, Thi Meagan (2001). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Voltage of a car battery". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- ^ a b "How to Get the Right Car Battery". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "Basic Battery Care". Popular Mechanics. 2006-03-29. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ Wert, Ray (2009-08-19). "2010 Porsche 911 GT3 RS: Track-Ready, Street-Legal And More Power". Jalopnik.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ "2017 Kia Niro: The Troublemaker - The Car Guide". amp.guideautoweb.com. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Automotive/SLI Batteries - Batteries by Fisher". Batteries by Fisher. Archived from the original on 2016-02-06. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- ^ a b "From Our Experts: Car Battery Tips". Consumer Reports. December 2, 2015. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- ^ "Winter Is Coming... Do You Know Your Battery's CCA Rating?". Bauer Built Inc. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2021-05-14.

- ^ "Marine Battery vs. Car Battery: What Are the Differences?". October 4, 2018.

- ^ "BCI Battery Service Manual 14th Edition - Download - Battery Council International". batterycouncil.org. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- ^ "bci-battery-technical-manual". yumpu.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- ^ Ruetschi, Paul (March 10, 2004), "Aging mechanisms and service life of lead–acid batteries", Journal of Power Sources, 127 (1–2): 33–44, Bibcode:2004JPS...127...33R, doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2003.09.052

- ^ "Car batteries Buying Guide", Consumer Reports, August 2016

- ^ The Most Common Reasons for 12 Volt Car Battery Drain

- ^ Magliozzi, Tom; Magliozzi, Ray (April 1, 2007), "Is revving the engine a good idea during a jump-start? Find out", Car Talk, Tappet Brothers

- ^ Meyer, Alex (17 December 2017). "Why do car batteries corrode?". Gear4Wheels.

- ^ "How to Clean Corroded Car Battery Terminals". wikiHow.

- ^ "Description and treatment of sulphated batteries using the mmf charger and the discharger/analyzer".

- ^ Witte, O.A. (1922). The Automotive Storage Battery Its Care and Repair. The American Bureau of Engineering.

(Full text via Project Gutenberg.)

- ^ Johnson, Larry. "Battery Tutorial". chargingchargers.com. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- ^ "Who Knew? A Car Battery Is the World's Most Recycled Product". Green Car Reports. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ^ "Projects Reports". WorstPolluted.org. Retrieved 2016-02-18.