David Livingstone

David Livingstone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 March 1813 Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK |

| Died | 1 May 1873 (aged 60) Chief Chitambo's Village (in modern-day Zambia) |

| Cause of death | Malaria and internal bleeding due to dysentery |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, London, England, UK 51°29′58″N 0°07′39″W / 51.499444°N 0.1275°W |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Exploration of Africa |

| Spouse(s) | Mary (née Moffat; m. 1845 – 27 April 1862; her death); 6 children |

David Livingstone (19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish Congregationalist pioneer medical missionary with the London Missionary Society and an explorer in Africa. His meeting with H. M. Stanley on 10 November 1871 gave rise to the popular quotation "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Perhaps one of the most popular national heroes of the late 19th century in Victorian Britain, Livingstone had a mythic status, which operated on a number of interconnected levels: Protestant missionary martyr, working-class "rags to riches" inspirational story, scientific investigator and explorer, imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of commercial empire. His fame as an explorer helped drive forward the obsession with discovering the sources of the River Nile that formed the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration of the African continent. [citation needed]

At the same time, his missionary travels, "disappearance" and death in Africa, and subsequent glorification as posthumous national hero in 1874 led to the founding of several major central African Christian missionary initiatives carried forward in the era of the European "Scramble for Africa".[1]

Early life

David Livingstone was born on 19 March 1813 in the mill town of Blantyre, Scotland, in a tenement building for the workers of a cotton factory on the banks of the Clyde River under the bridge crossing into Bothwell,[2] the second of seven children born to Neil Livingstone (1788–1856) and his wife, Agnes (née Hunter; 1782–1865). David was employed at the age of 10 in the cotton mill of Henry Monteith & Co. in Blantyre Works. David and his brother John worked twelve-hour days as piecers, tying broken cotton threads on the spinning machines. He was a student at the Charing Cross Hospital Medical School from 1838–40; his courses covered medical practice, midwifery and botany.

Neil Livingstone was a Sunday school teacher and teetotaller, who handed out Christian tracts on his travels as a door to door tea salesman, and who read extensively books on theology, travel and missionary enterprises. This rubbed off on the young David, who became an avid reader, but he also loved scouring the countryside for animal, plant and geological specimens in local limestone quarries. Neil Livingstone had a fear of science books as undermining Christianity and attempted to force his son to read nothing but theology, but David's deep interest in nature and science led him to investigate the relationship between religion and science.[3] In 1832, after reading Philosophy of a Future State, written by Thomas Dick, he found the rationale he needed to reconcile faith and science, and apart from the Bible, this book was perhaps his greatest philosophical influence.[4]

Other significant influences in his early life were Thomas Burke, a Blantyre evangelist and David Hogg, his Sabbath school teacher.[4] At age nineteen, David and his father left the Church of Scotland for a local Congregational church, influenced by preachers like Ralph Wardlaw, who denied predestinatarian limitations on salvation. Influenced by American revivalistic teachings, Livingstone's reading of the missionary Karl Gützlaff's Appeal to the Churches of Britain and America on behalf of China enabled him to persuade his father that medical study could advance religious ends.[5]

Livingstone's experiences from ages 10 to 26 in H. Monteith's Blantyre cotton mill, first as a piecer and later as a spinner, were also important. Necessary to support his impoverished family, this work was monotonous but taught him persistence, endurance, and a natural empathy with all who labour, as expressed by lines he used to hum from the egalitarian Rabbie Burns song: "When man to man, the world o'er/Shall brothers be for a' that".[6]

Livingstone attended Blantyre village school along with the few other mill children with the endurance to do so despite their 14-hour workday (6 am–8 pm), but having a family with a strong, ongoing commitment to study also reinforced his education. After reading the appeal by Gutzlaff for medical missionaries for China in 1834, he began saving money and in 1836 entered Anderson's College, Glasgow (now University of Strathclyde), founded to bring science and technology to ordinary folk, and attended Greek and theology lectures at the University of Glasgow.[7] To enter medical school he required some knowledge of Latin. A local Roman Catholic, Daniel Gallagher, helped him learn Latin to the required level. Later in life Gallagher became a priest and founded the third oldest Catholic Church in Glasgow, St Simon's, Partick (originally named St Peter's). A painting of both Gallagher and Livingstone by Roy Petrie [who?] hangs in that church's coffee room. In addition, he attended divinity lectures by Wardlaw, a leader at this time of vigorous anti-slavery campaigning in the city. Shortly after, he applied to join the London Missionary Society (LMS) and was accepted subject to missionary training. He continued his medical studies in London while training there and was attached to a church in Ongar, Essex, to be a minister under LMS.[5] Despite his impressive personality, he was a plain preacher and would have been rejected by the LMS had not the director given him a second chance to pass the course.[4]

Livingstone hoped to go to China as a missionary, but the First Opium War broke out in September 1839 and the LMS suggested the West Indies instead. In 1840, while continuing his medical studies in London, Livingstone met LMS missionary Robert Moffat, on leave from Kuruman, a missionary outpost in South Africa, north of the Orange River. Excited by Moffat's vision of expanding missionary work northwards, and influenced by abolitionist T.F. Buxton's arguments that the African slave trade might be destroyed through the influence of "legitimate trade" and the spread of Christianity, Livingstone focused his ambitions on Southern Africa.[5]

Livingstone was deeply influenced by Moffat's judgement that he was the right person to go to the vast plains to the north of Bechuanaland, where he had glimpsed "the smoke of a thousand villages, where no missionary had ever been."[4] During this time, he was attacked by a lion while staying in an African village, while trying to defend the village's sheep from the animal. The lion heavily wounded his left arm, and the wounds disabled his arm for the rest of his life.[8] He lived in Hamilton, South Lanarkshire in 1862 for a short time. The house still stands and has a plaque that can be seen outside the house (17 Burnbank Road). He was awarded the Freedom of the Town of Hamilton. [citation needed].

Exploration of southern and central Africa

After the Kolobeng Mission had to be closed because of drought, Livingstone explored the African interior to the north, in the period 1852–56, and was the first European to see the Mosi-oa-Tunya ("the smoke that thunders") waterfall (which he renamed Victoria Falls after his monarch, Queen Victoria), of which he wrote later, "Scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight." (Jeal, p. 149)

Livingstone was one of the first Westerners to make a transcontinental journey across Africa, Luanda on the Atlantic to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean near the mouth of the Zambezi, in 1854–56.[4] Despite repeated European attempts, especially by the Portuguese, central and southern Africa had not been crossed by Europeans at that latitude owing to their susceptibility to malaria, dysentery and sleeping sickness which was prevalent in the interior and which also prevented use of draught animals (oxen and horses), as well as to the opposition of powerful chiefs and tribes, such as the Lozi, and the Lunda of Mwata Kazembe.

The qualities and approaches which gave Livingstone an advantage as an explorer were that he usually travelled lightly, and he had an ability to reassure chiefs that he was not a threat. Other expeditions had dozens of soldiers armed with rifles and scores of hired porters carrying supplies, and were seen as military incursions or were mistaken for slave-raiding parties. Livingstone on the other hand travelled on most of his journeys with a few servants and porters, bartering for supplies along the way, with a couple of guns for protection. He preached a Christian message but did not force it on unwilling ears; he understood the ways of local chiefs and successfully negotiated passage through their territory, and was often hospitably received and aided, even by Mwata Kazembe.[4]

Livingstone was a proponent of trade and Christian missions to be established in central Africa. His motto, inscribed in the base of the statue dedicated to him at Victoria Falls, was "Christianity, Commerce and Civilization". The reason he emphasised these three was that they would form an alternative to the slave trade, which was still rampant in Africa at that time, which would give the Africans some dignity vis a vis the Europeans. It was the abolition of the African slave trade that became his primary motivation.[9] Around this time he believed the key to achieving these goals was the navigation of the Zambezi River as a Christian commercial highway into the interior.[10] He returned to Britain to try to garner support for his ideas, and to publish a book on his travels which brought him fame as one of the leading explorers of the age.

Believing he had a spiritual calling for exploration to find routes for commercial trade which would displace slave trade routes, rather than preaching, and encouraged by the response in Britain to his discoveries and support for future expeditions, in 1857 he resigned from the London Missionary Society. According to his sympathetic biographer, W. Garden Blaike, the reason was to prevent public concerns that his scientific work might show the LMS to be "departing from the proper objects of a missionary body". Livingstone had written to Directors of the society to express complaints about their policies and the clustering of too many missionaries near the Cape Colony despite the sparse native population.[4] With the help of the Royal Geographical Society's president, Livingstone was appointed as Her Majesty's Consul for the East Coast of Africa.

Zambezi expedition

The British government agreed to fund Livingstone's idea and he returned to Africa as head of the Zambezi Expedition to examine the natural resources of southeastern Africa and open up the River Zambezi. Unfortunately it turned out to be completely impassable to boats past the Cahora Bassa rapids, a series of cataracts and rapids that Livingstone had failed to explore on his earlier travels.[10]

The expedition lasted from March 1858 until the middle of 1864. Expedition members recorded that Livingstone was an inept leader incapable of managing a large-scale project. He was also said to be secretive, self-righteous, moody and could not tolerate criticism which severely strained the expedition and which led to his physician, John Kirk, writing in 1862, "I can come to no other conclusion than that Dr. Livingstone is out of his mind and a most unsafe leader".[11]

Artist Thomas Baines was dismissed from the expedition on charges (which he vigorously denied) of theft. The expedition became the first to reach Lake Malawi and they explored it in a four-oared gig. In 1862 they returned to the coast to await the arrival of a steam boat specially designed to sail on Lake Malawi. Mary Livingstone arrived along with the boat. She died on 27 April 1862 from malaria and Livingstone continued his explorations. Attempts to navigate the Ruvuma River failed because of the continual fouling of the paddle wheels from the bodies thrown in the river by slave traders, and Livingstone's assistants gradually died or left him.[11] It was at this point that he uttered his most famous quote, "I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward." He eventually returned home in 1864 after the government ordered the recall of the expedition because of its increasing costs and failure to find a navigable route to the interior. The Zambezi Expedition was castigated as a failure in many newspapers of the time, and Livingstone experienced great difficulty in raising funds to further explore Africa. Nevertheless, John Kirk, Charles Meller, and Richard Thornton, the scientists appointed to work under Livingstone, did contribute large collections of botanic, ecological, geological and ethnographic material to scientific Institutions in the United Kingdom.[11]

The River Nile

In January 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa, this time to Zanzibar, from where he set out to seek the source of the Nile. Richard Francis Burton, John Hanning Speke and Samuel Baker had (although there was still serious debate on the matter) identified either Lake Albert or Lake Victoria as the source (which was partially correct, as the Nile "bubbles from the ground high in the mountains of Burundi halfway between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria"[12]). Livingstone believed the source was farther south and assembled a team of freed slaves, Comoros Islanders, twelve Sepoys and two servants, Chuma and Susi, from his previous expedition to find it. [citation needed]

Setting out from the mouth of the Ruvuma river, Livingstone's assistants gradually began deserting him. The Comoros Islanders had returned to Zanzibar and informed authorities that Livingstone had died. He reached Lake Malawi on 6 August, by which time most of his supplies, including all his medicines, had been stolen. Livingstone then travelled through swamps in the direction of Lake Tanganyika. With his health declining he sent a message to Zanzibar requesting supplies be sent to Ujiji and he then headed west. Forced by ill health to travel with slave traders, he arrived at Lake Mweru on 8 November 1867 and continued on, travelling south to become the first European to see Lake Bangweulu. Upon finding the Lualaba River, Livingstone theorized it could have been the high part of the Nile River; but realized it in fact flowed into the River Congo at Upper Congo Lake.[13]

The year 1869 began with Livingstone finding himself extremely ill while in the jungle. He was saved by Arab traders who gave him medicines and carried him to an Arab outpost.[14] In March 1869, Livingstone, suffering from pneumonia, arrived in Ujiji to find his supplies stolen. Coming down with cholera and tropical ulcers on his feet he was again forced to rely on slave traders to get him as far as Bambara where he was caught by the wet season. With no supplies, Livingstone had to eat his meals in a roped off open enclosure for the entertainment of the locals in return for food.[11]

On 15 July 1871[15] while visiting Nyangwe on the banks of the Lualaba River, he witnessed around 400 Africans being massacred by slavers.[16] The massacre horrified Livingstone, leaving him too shattered to continue his mission to find the source of the Nile.[15] Following the end of the wet season, he travelled 240 miles (390 km) from Nyangwe – violently ill most of the way – back to Ujiji, an Arab settlement on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, arriving on 23 October 1871. [citation needed]

Geographical discoveries

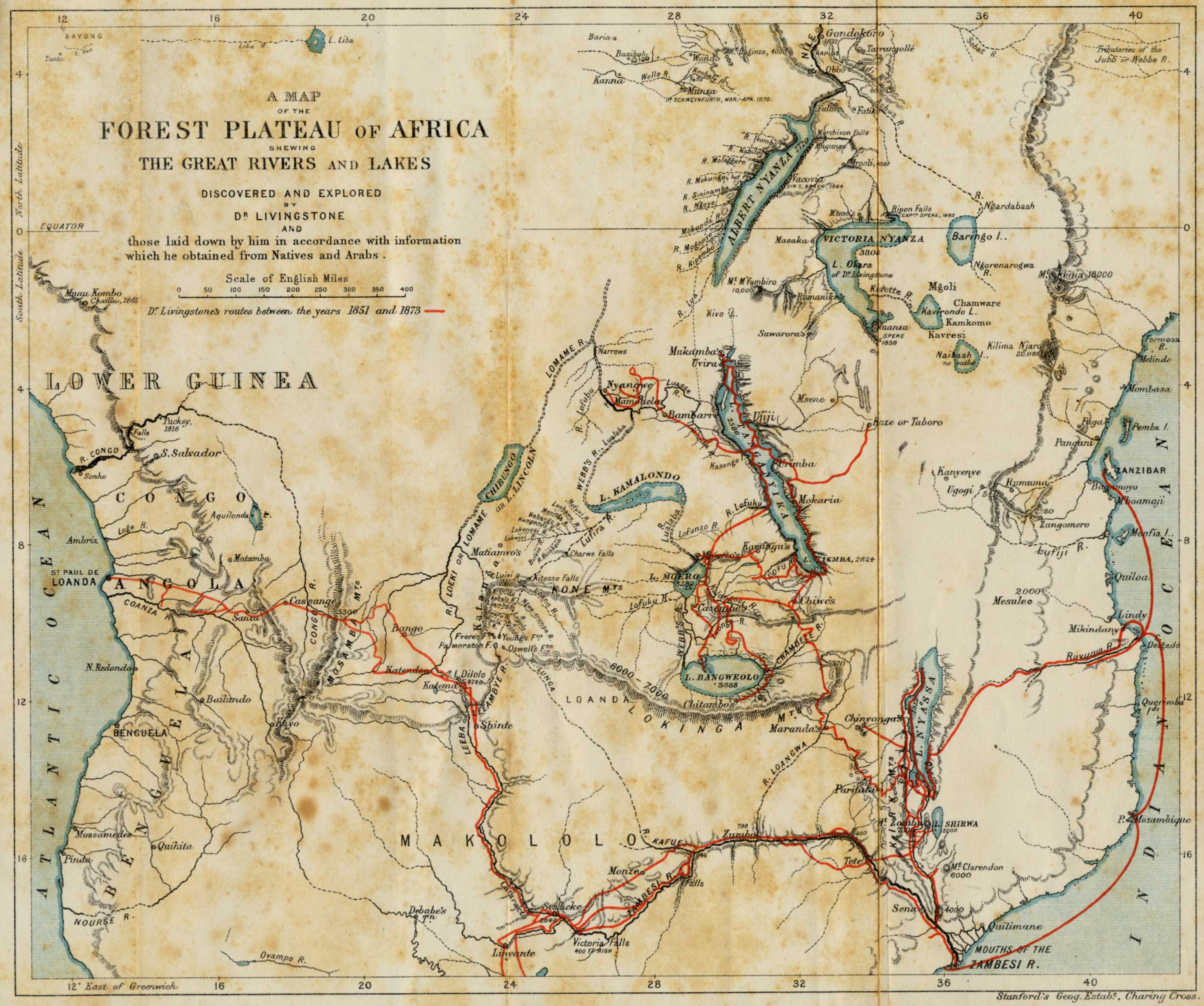

Although Livingstone was wrong about the Nile, he discovered for Western science numerous geographical features, such as Lake Ngami, Lake Malawi, and Lake Bangweulu in addition to Victoria Falls mentioned above. He filled in details of Lake Tanganyika, Lake Mweru and the course of many rivers, especially the upper Zambezi, and his observations enabled large regions to be mapped which previously had been blank. Even so, the farthest north he reached, the north end of Lake Tanganyika, was still south of the Equator and he did not penetrate the rainforest of the River Congo any further downstream than Ntangwe near Misisi.[17]

Livingstone was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society of London and was made a Fellow of the society, with which he had a strong association for the rest of his life.[4]

Stanley meeting

Livingstone completely lost contact with the outside world for six years and was ill for most of the last four years of his life. Only one of his 44 letter dispatches made it to Zanzibar. One surviving letter to Horace Waller, made available to the public in 2010 by its owner Peter Beard, reads: "I am terribly knocked up but this is for your own eye only, ... Doubtful if I live to see you again ..."[18][19]

Henry Morton Stanley, who had been sent to find him by the New York Herald newspaper in 1869, found Livingstone in the town of Ujiji on the shores of Lake Tanganyika on 10 November 1871,[20] greeting him with the now famous words "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" to which he responded "Yes", and then "I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you." These famous words may have been a fabrication, as Stanley later tore out the pages of this encounter in his diary.[21] Even Livingstone's account of this encounter does not mention these words. However, the phrase appears in a New York Herald editorial dated 10 August 1872, and the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; both quote it without questioning its veracity. The words are famous because of their perceived tongue-in-cheek humorous nature: Dr. Livingstone was the only white person for hundreds of miles. Stanley's book suggests that it was really because of embarrassment, because he did not dare to embrace him.

Despite Stanley's urgings, Livingstone was determined not to leave Africa until his mission was complete. His illness made him confused and he had judgment difficulties at the end of his life. He explored the Lualaba and, failing to find connections to the Nile, returned to Lake Bangweulu and its swamps to explore possible rivers flowing out northwards.[22]

Christianity and Sechele

Although Livingstone is known as "Africa's greatest missionary,” he is recorded as having converted only one African: Sechele, who was the chief of the Kwena people of Botswana. (Kwena, one of the main Sotho-Tswana clans, are found in South Africa, Lesotho and Botswana[23] in all three Sotho-Tswana language groupings.) Sechele was born in 1812. At the age of 10, his father died, and two of his uncles divided the tribe, which forced Sechele to leave his home for nine years. When Sechele returned, he took over one of his uncle's tribes; at that point he met David Livingstone.[24][pages needed]

Livingstone was known through a large part of Africa for treating the natives with respect. Although the tribes he visited returned his respect with faith and loyalty, he could never permanently convert the tribesmen to Christianity. Among other reasons, Sechele, by then the leader of the African tribe, did not like the way Livingstone could not demand rain of his God, like his rainmakers, who said they could. After long hesitation from Livingstone, he baptised Sechele and had the church completely embrace him. Although Sechele was now a part of the church, he continued to act according to his African culture, which went against Livingstone's teachings.[25][pages needed]

Sechele was no different from any other man of his tribe in believing in polygamy. He had five wives, and when Livingstone told him to get rid of four of them, it shook the foundations of the Kwena tribe. After he finally divorced the women, Livingstone baptised them all and everything went well. However, one year later one of his ex-wives became pregnant and Sechele was the father. Although Sechele begged Livingstone to not give up on him because his faith was still strong, Livingstone left the country and went north to continue his Christianizing attempts.[26][pages needed]

Livingstone, and especially his ability to read, immediately interested Sechele. Being a quick learner, Sechele learned the alphabet in two days and soon called English a second language. After teaching his wives the skill, he wrote the Bible in his native tongue.[27][pages needed]

After Livingstone left the Kwena tribe, Sechele remained faithful to Christianity and led missionaries to surrounding tribes as well as nearly converting his entire Kwena people. In the estimation of Neil Parsons, of the University of Botswana, Sechele "did more to propagate Christianity in 19th-century southern Africa than virtually any single European missionary". Although Sechele was a self-proclaimed Christian, many European missionaries disagreed. The Kwena tribe leader kept rainmaking a part of his life as well as polygamy.[28]

Death

Livingstone died in that area in Chief Chitambo's village at Ilala southeast of Lake Bangweulu in present-day Zambia on 1 May 1873 from malaria and internal bleeding caused by dysentery. He took his final breaths while kneeling in prayer at his bedside. (His journal indicates that the date of his death would have been 1 May, but his attendants noted the date as 4 May, which they carved on a tree and later reported; this is the date on his grave.) His two followers, Susi and Chuma, on the morning of his death made the decision to remove the heart and prepare the body for carrying to the coast for subsequent shipping to England.[29]

Livingstone's heart was buried under a Mvula tree near the spot where he died, now the site of the Livingstone Memorial.[30] His body together with his journal was carried over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) by his loyal attendants Chuma and Susi to the coast to Bagamoyo, and was returned to Britain for burial. After lying in repose at No.1 Savile Row — then headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society, now the home of bespoke tailors Gieves & Hawkes — his remains were interred at Westminster Abbey, London.[4][31]

Livingstone and slavery

And if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.

— Livingstone in a letter to the editor of the New York Herald[32]

Livingstone wrote of the slave trade in the African Great Lakes region, which he visited in the mid-nineteenth century:

We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path. [Onlookers] said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer.[33]

Livingstone's letters, books, and journals[22] did stir up public support for the abolition of slavery;[34] however, he became humiliatingly dependent for assistance on the very slave-traders whom he wished to put out of business. Because he was a poor leader of his peers, he ended up on his last expedition as an individualist explorer with servants and porters but no expert support around him. At the same time he did not use the brutal methods of maverick explorers such as Stanley to keep his retinue of porters in line and his supplies secure. For these reasons from 1867 onwards he accepted help and hospitality from Mohamad Bogharib and Mohamad bin Saleh (also known as "Mpamari"), traders who kept and traded in slaves, as he recounts in his journals, and they benefited from Livingstone's influence with local people, which facilitated Mpamari's release from bondage to Mwata Kazembe. Livingstone was furious to discover some of the replacement porters sent at his request from Ujiji were slaves.[22]

Legacy

By the late 1860s Livingstone's reputation in Europe had suffered owing to the failure of the missions he set up, and of the Zambezi Expedition; and his ideas about the source of the Nile were not supported. His expeditions were hardly models of order and organisation. His reputation was rehabilitated by Stanley and his newspaper,[10] and by the loyalty of Livingstone's servants whose long journey with his body inspired wonder. The publication of his last journal revealed stubborn determination in the face of suffering.[4]

Livingstone made geographical discoveries for European knowledge. He inspired abolitionists of the slave trade, explorers and missionaries. He opened up Central Africa to missionaries who initiated the education and health care for Africans, and trade by the African Lakes Company. He was held in some esteem by many African chiefs and local people and his name facilitated relations between them and the British.[4]

Partly as a result, within 50 years of his death, colonial rule was established in Africa, and white settlement was encouraged to extend further into the interior. However, what Livingstone envisaged for "colonies" was not of what we now know as colonial rule, but of settlements of dedicated Christian Europeans who would live among the people to help them work out ways of living that did not involve slavery.[9] Livingstone was part of an evangelical and nonconformist movement in Britain which during the 19th century changed the national mindset from the notion of a divine right to rule 'lesser races', to ethical ideas in foreign policy which, with other factors, contributed to the end of the British Empire.[35]

The David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre celebrates his life and is based in the house in which he was born, on the site of the mill in which he started his working life. His Christian faith is evident in his journal, in which one entry reads: "I place no value on anything I have or may possess, except in relation to the kingdom of Christ. If anything will advance the interests of the kingdom, it shall be given away or kept, only as by giving or keeping it I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all my hopes in time and eternity."[36]

In 2002, David Livingstone was named among the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.[37]

Family life

While Livingstone had a great impact on British Imperialism, he did so at a tremendous cost to his family. In his absences, his children grew up missing their father, and his wife Mary (daughter of Mary and Robert Moffat), whom he wed in 1845, endured very poor health, and died of malaria on 27 April 1862[38] trying to follow him in Africa. He had six children: Robert reportedly died in the American Civil War;[39] Agnes (b. 1847), Thomas, Elizabeth (who died at two months), William Oswell (nicknamed Zouga because of the river along which he was born, in 1851) and Anna Mary (b. 1858). Only Agnes, William Oswell and Anna Mary married and had children.[40] His one regret in later life was that he did not spend enough time with his children.[41]

Archives

The archives of David Livingstone are maintained by the Archives of the University of Glasgow (GUAS). On 11 November 2011, Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary, as well as other original works, was published online for the first time by the David Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project.[42]

Papers relating to Livingstone's time as a London Missionary Society missionary (including hand-annotated maps of South East Africa) are held by the Archives of the School of Oriental and African Studies.[43]

Places named in his honour and other memorials

In Africa

- The Livingstone Memorial in Ilala, Zambia marks where David Livingstone died.

- The city of Livingstone, Zambia, which includes a memorial in front of the Livingstone Museum and a new statue erected in 2005.[44]

- The Rhodes–Livingstone Institute in Livingstone and Lusaka, Zambia, 1940s to 1970s, was a pioneering research institution in urban anthropology. [citation needed]

- David Livingstone Teachers' Training College, Livingstone, Zambia.

- The David Livingstone Memorial statue at Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, erected in 1934 on the western bank of the falls.[45][46]

- A new statue of David Livingstone was erected in November 2005 on the Zambian side of Victoria Falls.[44]

- A plaque was unveiled in November 2005 at Livingstone Island on the lip of Victoria Falls marking where Livingstone stood to get his first view of the falls.[44]

- Livingstone Hall, Men's Hall of residence at Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

- The town of Livingstonia, Malawi.

- The city of Blantyre, Malawi is named after Livingstone's birthplace in Scotland, and includes a memorial.

- The David Livingstone Scholarships for students at the University of Malawi, funded through Strathclyde University, Scotland.

- The David Livingstone Clinic was founded by the University of Strathclyde's Millennium Project in Lilongwe, Malawi.[47]

- The Kipengere Range in south-west Tanzania at the north-eastern end of Lake Malawi is also called the Livingstone Mountains.

- Livingstone Falls on the River Congo, named by Stanley.

- The Livingstone Inland Mission, a Baptist mission to the Congo Free State 1877–1884, located in present-day Kinshasa, Zaire.

- A memorial in Ujiji commemorates his meeting with Stanley. [citation needed]

- The Livingstone–Stanley Monument in Mugere (present-day Burundi) marks a spot that Livingstone and Stanley visited on their exploration of Lake Tanganyika, mistaken by some as the first meeting place of the two explorers.

- Scottish Livingstone Hospital in Molepolole 50 km west of Gaborone, Botswana

- There is a memorial to Livingstone at the ruins of the Kolobeng Mission, 40 km west of Gaborone, Botswana.

- The church tower of the Holy Ghost Mission (Roman Catholic) in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, is sometimes called "Livingstone Tower" as Livingstone's body was laid down there for one night before it was shipped to London. [citation needed]

- Livingstone House in Stone Town, Zanzibar, provided by the Sultan for Livingstone's use, January to March 1866, to prepare his last expedition; the house was purchased by the Zanzibar government in 1947. [citation needed]

- Plaque commemorating his departure from Mikindani (present-day Tanzania) on his final expedition on the wall of the house that has been built over the house he reputedly stayed in.

- David Livingstone Primary School in Salisbury, Rhodesia (present-day Harare, Zimbabwe).

- David Livingstone Secondary School in Ntabazinduna about 40 km from Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

- David Livingstone Senior Secondary School in Schauderville, Port Elizabeth, South Africa.

- Livingstone House in Harare, Zimbabwe, designed by Leonora Granger. [who?]

- Livingstone House, Achimota School, Ghana (boys' boarding house).

- Livingstone Street, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

In New Zealand

- Livingstone Street in Westmere, Auckland

- Livingstone Road in Flaxmere, Hastings

In Scotland

- A statue stands near the base of the Scott Monument in the Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- The David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre, Scotland, is a museum in his honour.

- David Livingstone Memorial Primary School in his birthplace, Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

- David Livingstone Memorial Church of the Church of Scotland, in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

- A statue of Livingstone is sited in Cathedral Square, Glasgow.

- A bust of David Livingstone is among those of famous Scotsmen in the William Wallace Memorial near Stirling, Scotland.

- Strathclyde University, Glasgow (successor to Anderson's University), commemorates him in the David Livingstone Centre for Sustainability[48] and the Livingstone Tower where there is a statue of him.

- The David Livingstone (Anderson College) Memorial Prize in Physiology commemorates him at the University of Glasgow.

- Livingstone Place, a street in the Marchmont neighbourhood of Edinburgh.

- Livingstone Street in Addiewell.

- A memorial plaque commemorating the centenary of Livingstone's birth was dedicated in St. James's Congregational Church, the church he attended as a boy.[49]

In London

- A statue of David Livingstone stands in a niche on the outer wall of the Royal Geographical Society on Kensington Gore, London, looking out across Kensington Gardens. It was unveiled in 1953[50]

In Canada

- The Livingstone Range of mountains in southern Alberta.

- David Livingstone Elementary School, Vancouver.

- David Livingstone Community School, Winnipeg.

- Bronze bust in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

- Gold bust in the city of Borden, Ontario.

- Livingstone Avenue in Barrie, Ontario.

In the USA

- Livingstone College, Salisbury, North Carolina.

- Livingstone Adventist Academy, Salem, Oregon.

In South America

- The Livingstone Healthservice in Jardìn Amèrica, Misiones, Argentina is named in his honour.[51]

Banknotes

From 1971–1998 Livingstone's image was portrayed on £10 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank. He was originally shown surrounded by palm tree leaves with an illustration of African tribesmen on the back.[52] A later issue showed Livingstone against a background graphic of a map of Livingstone's Zambezi expedition, showing the River Zambezi, Victoria Falls, Lake Nyasa and Blantyre, Malawi; on the reverse, the African figures were replaced with an image of Livingstone's birthplace in Blantyre, Scotland.[53]

Biology

The following species have been named in honour of David Livingstone:

- Lake Malawi Cichlid Nimbochromis livingstonii

- Livingstone's eland, Taurotragus oryx livingstonii

- Livingstone's Turaco, Tauraco livingstonii

- Livingstone's fruit bat, Pteropus livingstonii

Portrayal in film

Livingstone has been portrayed by M.A. Wetherell in Livingstone (1925), Percy Marmont in David Livingstone (1936), Sir Cedric Hardwicke in Stanley and Livingstone (1939), Bernard Hill in Mountains of the Moon (1990) and Sir Nigel Hawthorne in the TV movie Forbidden Territory (1997).[citation needed]

The 1949 comedy film Africa Screams is the story of a dimwitted clerk named Stanley Livington (played by Lou Costello), who is mistaken for a famous African explorer and recruited to lead a treasure hunt. The character's name appears to be a play on Stanley & Livingstone, but with a few crucial letters omitted from the surname; it is unknown whether this results from a typist's error or a deliberate obfuscation.

See also

Notes

- ^ John M. Mackenzie, "David Livingstone: The Construction of the Myth," in Sermons and Battle Hymns: Protestant Popular Culture in Modern Scotland, ed. Graham Walker and Tom Gallagher (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990)

- ^ The National Trust for Scotland: David Livingstone Centre, Birthplace Of Famous Scot, website accessed 22 April 2007.

- ^ Ross, Andrew C., David Livingstone: Mission and Empire (2002), London: Hambledon, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blaikie, William Garden (1880): The Personal Life of David Livingstone Project Gutenberg E-book #13262, release date 23 August 2004.

- ^ a b c A.D. Roberts, "Livingstone, David (1813–1873)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

- ^ Blaikie (1880). This sentiment today would be expressed along the lines of: "all people, worldwide, are brothers and sisters, despite everything."

- ^ University of Glasgow: Biography of David Livingstone; retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ Wholesome Words website

- ^ a b Stephen Tomkins (2013), David Livingstone, The Unexplored Story, Oxford Lion.

- ^ a b c Tim Holmes: "The History" in: Spectrum Guide to Zambia. Camerapix International Publishers, Nairobi (1996)

- ^ a b c d Wright, Ed (2008). Lost Explorers. Murdock Books. ISBN 978-1-74196-139-3.

- ^ 'Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley and Livingstone' (2003), Martin Dugard [page needed]

- ^ Livingstone, David. "Personal Letter to J. Kirk or R. Playfair". David Livingstone Online. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Project Gutenberg, The Last Journal of David Livingstone; accessed 24 May 2012.

- ^ a b Livingstone, David (2012). Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. A Multispectral Critical Edition, UCLA Digital Library: Los Angeles, California; available here

- ^ See also Jeal, Tim (1973). Livingstone, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 331–335.

- ^ "Map of Livingstone's travels", National Museums of Scotland. The map is online here (subscription required)

- ^ "David Livingstone letter deciphered at last. Four-page missive composed at the lowest point in his professional life". Associated Press. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Livingstone's Letter from Bambarre, emelibrary.org; accessed 4 July 2010.

- ^ Henry Morton Stanley. "How I found Livingstone". Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-22102-5.

- ^ a b c David Livingstone and Horace Waller (ed.): The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to his Death. Two volumes, John Murray, London, 1874.

- ^ Tomkins, Stephen. "The African Chief Converted to Christianity by Dr Livingstone". BBC News.

- ^ Ross, Andrew (2002), David Livingstone: Mission and Empire, London, UK.

- ^ Horne, Silvester (1999). David Livingstone: Man of Prayer and Action. Arlington Heights: Christian Liberty.

- ^ Tomkins, Stephen (2013). David Livingstone: The Unexplored Story. Oxford Lion.

- ^ Livingstone, David (1912). Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: J. Murray.

- ^ Tomkins, Stephen (2013), "The African Chief Converted to Christianity by Dr Livingstone", BBC News

- ^ Profile, biographyonline.net; accessed 6 January 2014.

- ^ Bradford,Charles Angell (1933). Heart Burial. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 242. ISBN 9-781162-771816.

- ^ G. Bruce Boyer (Summer 1996). "On Savile Row". Cigar Aficionado. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Stanley Henry M., How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa, including an account of four months' residence with Dr. Livingstone. (1871)

- ^ David Livingstone (2006). The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, Echo Library. p. 46; ISBN 1-84637-555-X

- ^ BBC.co.uk/History Historic Figures: "David Livingstone profile" at BBC.co.uk; accessed 1 February 2007.

- ^ Corelli Barnett. The Audit of War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation (Macmillan, 1986)

- ^ Neill. A History of Christian Missions. p. 315.

- ^ "100 great Britons – A complete list". Daily Mail. 21 August 2002. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 687.

- ^ Chirgwin, A. M. (1934). "New Light on Robert Livingstone". Journal of the Royal African Society. 33 (132): 250–252. JSTOR 716469.

- ^ Steven Wilson. "Livingstone Descendants". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Empire: The rise and demise of the British world order and the lessons for global power by Niall Ferguson, Basic Books, 2003.

- ^ David Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project, livingstone.library.ucla.edu; accessed 30 March 2014.

- ^ "Images of Livingstone letter now available online". SOAS, University of London. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ a b c The Times of Zambia online: "David Livingstone remembered", 15 November 2005 – 23 November 2005; accessed 26 April 2007.

- ^ Ian Michler (2007). "Victoria Falls and Surrounds: The Insider's Guide", p. 11

- ^ The "Insider's Guide" quoted 1954 which is wrong. The statue was unveiled on 05.08.1934 see photo at: www.rhodesia.me.uk/VictoriaFalls.htm

- ^ David Livingstone Clinic webpage

- ^ David Livingstone Centre for Sustainability webpage

- ^ "David Livingstone – a brief history". Hamilton.urc.org.uk. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ The Geographical Journal, Vol. 120, No. 1, Mar. 1954, pp 15-20

- ^ Livingstone Healthservice

- ^ "Clydesdale 10 Pounds, 1982". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Clydesdale 10 Pounds, 1990". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

References

- Holmes, Timothy (1993). Journey to Livingstone: Exploration of an Imperial Myth. Edinburgh: Canongate Press. ISBN 978-0-86241-402-3; scholarly biography

- Jeal, Tim (1973). Livingstone. London, UK: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-37208-0., scholarly biography

- Livingstone, David (1905) [1857]. Journeys in South Africa, or Travels and Researches in South Africa. London, UK: The Amalgamated Press Ltd.

- Livingstone, David and James I. Macnair (eds) (1954). Livingstone's Travels. London, UK: J.M. Dent.

- Livingstone, David (1999) [1875]. Dernier Journal. Paris: Arléa; ISBN 2-86959-215-9 Template:Fr icon

- Maclachlan, T. Banks. David Livingstone, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1901, ("Famous Scots Series").

- Martelli, George (1970). Livingstone's River: A History of the Zambezi Expedition, 1858–1864. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1527-2

- Morrill, Leslie, and Madge Haines (1959). Livingstone, Trail Blazer for God. Mountain View: Pacific Press Publication Association.

- Philip, M. NourbeSe (1991). Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence. Stratford: The Mercury Press; ISBN 978-0-920544-88-4

- Ross, Andrew C. (2002). David Livingstone: Mission and Empire. London and New York: Hambledon and London; ISBN 978-1-85285-285-6

- Seaver, George. David Livingston: His Life and Letters (1957), a standard biography

- Waters, John (1996). David Livingstone: Trail Blazer. Leicester: Inter-Varsity; ISBN 978-0-85111-170-4

- Wisnicki, Adrian S. (2009). "Interstitial Cartographer: David Livingstone and the Invention of South Central Africa". Victorian Literature and Culture 37.1 (Mar.): 255–71.

External links

- Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. Many of Livingstone's original papers spectrally imaged.

- Livingstone Online – Explore the manuscripts of David Livingstone Images of original documents alongside transcribed, critically edited versions

- David Livingstone (c. 1956). Archive film from the National Library of Scotland: Scottish Screen Archive

- Works by David Livingstone at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about David Livingstone at the Internet Archive

- A Brief Biography of David Livingstone

- David Livingstone biographies

- "Dr. Livingston (obituary, Wed., 28 Jan. 1874)". Eminent persons: Biographies reprinted from the Times. Vol. 1–6. D. Vol I, 1870–1875. Macmillan & Co.: 225–236 1892Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - The Lost Diary of Dr. Livingstone Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

- How Livingstone discovered the Falls. by J. Desmond Clark M.A. PH.D. F.S.A. Curator of the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum. 1955

- David Livingstone

- Scottish explorers

- Scottish Christian missionaries

- British explorers

- Explorers of Africa

- Christian missionaries in Africa

- Scottish clergy

- Scottish theologians

- Scottish Congregationalists

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Christianity in Africa

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society

- People from Blantyre, South Lanarkshire

- 1813 births

- 1873 deaths

- Deaths from malaria

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- Infectious disease deaths in Zambia

- World Digital Library related

- Congregationalist missionaries

- Animal attack victims

- People educated at Charing Cross Medical School