Death of Azaria Chamberlain

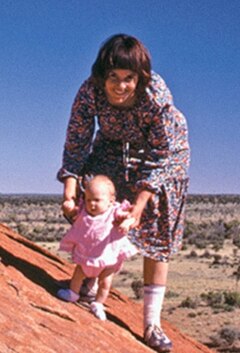

Azaria Chamberlain and her mother, Lindy | |

| Date | 17 August 1980 (aged 2 months 6 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Uluru (Ayers Rock), Northern Territory, Australia |

| Cause | Declared legally dead on 12 June 2012 (32 years later) "...the result of being attacked and taken by a dingo".[1][2] |

| Inquiries | Royal Commission of inquiry into Chamberlain convictions (1986–1987) |

| Inquest | |

| Coroner | 1. Denis Barritt; 2. Gerard Galvin; 3. John Lowndes; 4. Elizabeth Morris |

| Suspects |

|

| Accused | Lindy and Michael Chamberlain |

| Charges |

|

| Convictions |

|

Azaria Chamberlain (11 June 1980 – 17 August 1980) was an Australian baby girl who was killed by a dingo on the night of 17 August 1980 on a family camping trip to Uluru (aka Ayers Rock) in the Northern Territory. Her body was never found. Her parents, Lindy and Michael Chamberlain, reported that she had been taken from their tent by a dingo. Lindy Chamberlain was, however, tried for murder and spent more than three years in prison. She was released when a piece of Azaria's clothing was found near a dingo lair, and new inquests were opened. In 2012, some 32 years after Azaria's death, the Chamberlains' version of events was officially confirmed by a coroner.

An initial inquest held in Alice Springs supported the parents' claim and was highly critical of the police investigation. The findings of the inquest were broadcast live on television—a first in Australia. Subsequently, after a further investigation and a second inquest held in Darwin, Lindy Chamberlain was tried for murder, convicted on 29 October 1982 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Azaria's father, Michael Chamberlain, was convicted as an accessory after the fact and given a suspended sentence. The media focus for the trial was unusually intense and aroused accusations of sensationalism, while the trial itself was criticised for being unprofessional and biased. The Chamberlains made several unsuccessful appeals, including the final High Court appeal.

After all legal options had been exhausted, the chance discovery in 1986 of a piece of Azaria's clothing in an area full of dingo lairs led to Lindy Chamberlain's release from prison. On 15 September 1988, the Northern Territory Court of Criminal Appeals unanimously overturned all convictions against Lindy and Michael Chamberlain.[6] A third inquest was conducted in 1995, which resulted in an "open" finding.[5] At a fourth inquest held on 12 June 2012, Coroner Elizabeth Morris delivered her findings that Azaria Chamberlain had been taken and killed by a dingo. After being released, Lindy Chamberlain was paid $1.5 million for false imprisonment[7] and an amended death certificate was issued immediately.

Numerous books have been written about the case. The story has been made into a TV movie, the feature film Evil Angels (released outside of Australia and New Zealand as A Cry in the Dark), a TV miniseries, a play by Brooke Pierce, a concept album by Australian band The Paradise Motel and an opera, Lindy, by Moya Henderson.

Coroner's inquests

The initial coronial inquest into the disappearance was opened in Alice Springs on 15 December 1980 before magistrate Denis Barritt. On 20 February 1981, in the first live telecast of Australian court proceedings, Barritt ruled that the likely cause was a dingo attack. In addition to this finding, Barritt also concluded that, subsequent to the attack, "the body of Azaria was taken from the possession of the dingo, and disposed of by an unknown method, by a person or persons, name unknown".[3]

The Northern Territory Police and prosecutors were dissatisfied with this finding. Investigations continued, leading to a second inquest in Darwin in September 1981. Based on ultraviolet photographs of Azaria's jumpsuit, James Cameron of the London Hospital Medical College alleged that "there was an incised wound around the neck of the jumpsuit—in other words, a cut throat" and that there was an imprint of the hand of a small adult on the jumpsuit, visible in the photographs.[8] Following this and other findings, the Chamberlains were charged with Azaria's murder.

In 1995, a third inquest was conducted which failed to determine a cause of death, resulting in an "open" finding.[5]

In December 2011 the Northern Territory coroner, Elizabeth Morris, announced that a fourth inquest would be held in February 2012.[9] On 12 June 2012 at a fourth coronial inquest into the disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain, Morris ruled that a dingo was responsible for her death in 1980.[7] Morris made the finding in the light of subsequent reports of dingo attacks on humans causing injury and death. She stated, "Azaria Chamberlain died at Uluru, then known as Ayers Rock, on 17 August 1980. The cause of her death was as a result of being attacked and taken by a dingo."[7] Morris offered her condolences to the parents and brothers of Azaria Chamberlain "on the death of [their] special and dearly loved daughter and sister" and stated that a death certificate with the cause of death had been registered.[7]

Case against Lindy Chamberlain

The Crown alleged that Lindy Chamberlain had cut Azaria's throat in the front seat of the family car, hiding the baby's body in a large camera case. She then, according to the proposed reconstruction of the crime, rejoined the group of campers around a campfire and fed one of her sons a can of baked beans, before going to the tent and raising the cry that a dingo had taken the baby. It was alleged that at a later time, while other people from the campsite were searching, she disposed of the body.[10]

The key evidence supporting this allegation was the jumpsuit, as well as a highly contentious forensic report claiming to have found evidence of foetal haemoglobin in stains on the front seat of the Chamberlains' 1977 Torana hatchback.[11] Foetal haemoglobin is present in infants six months and younger; Azaria was nine weeks old at the time of her disappearance.[12]

Lindy Chamberlain was questioned about the garments that Azaria was wearing. She claimed that Azaria was wearing a matinee jacket over the jumpsuit, but the jacket was not present when the garments were found. She was questioned about the fact that Azaria's singlet, which was inside the jumpsuit, was inside out. She insisted that she never put a singlet on her babies inside out and that she was most particular about this. The statement conflicted with the state of the garments when they were collected as evidence.[13] The garments had been arranged by the investigating officer for a photograph.[citation needed]

In her defence, eyewitness evidence was presented of dingoes having been seen in the area on the evening of 17 August 1980. All witnesses claimed to believe the Chamberlains' story. One witness, a nurse, also reported having heard a baby's cry after the time when the prosecution alleged Azaria had been murdered.[14] Evidence was also presented that adult blood also passed the test used for foetal haemoglobin, and that other organic compounds can produce similar results on that particular test, including mucus from the nose and chocolate milkshakes, both of which had been present in the vehicle where Azaria was allegedly murdered.[citation needed]

Engineer Les Harris, who had conducted dingo research for over a decade, said that, contrary to Cameron's findings, a dingo's carnassial teeth can shear through material as tough as motor vehicle seat belts. He also cited an example of a captive female dingo removing a bundle of meat from its wrapping paper and leaving the paper intact.[15] His evidence was rejected, however.[citation needed]

Evidence to the effect that a dingo was strong enough to carry a kangaroo was also ignored. Also ignored was the removal of a three-year-old girl by a dingo from the back seat of a tourist's motor vehicle at the camping area just weeks before, an event witnessed by the parents.[citation needed]

The defence's case was rejected by the jury. Lindy Chamberlain was convicted of murder on 29 October 1982 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Michael Chamberlain was found guilty as an accessory after the fact[14] and was given an 18-month suspended sentence.

Appeals

An appeal was made to the High Court in November 1983.[16] Asked to quash the convictions on the ground that the verdicts were unsafe and unsatisfactory, in February 1984 the court refused the appeal by majority.[17]

Release and acquittal

The final resolution of the case was triggered by a chance discovery. In early 1986, English tourist David Brett fell to his death from Uluru during an evening climb. Because of the vast size of the rock and the scrubby nature of the surrounding terrain, it was eight days before Brett's remains were discovered, lying below the bluff where he had lost his footing and in an area full of dingo lairs. As police searched the area, looking for missing bones that might have been carried off by dingoes, they discovered a small item of clothing. It was quickly identified as the crucial missing piece of evidence from the Chamberlain case, Azaria's missing matinee jacket.[18]

The Chief Minister of the Northern Territory ordered Lindy Chamberlain's immediate release and the case was reopened. On 15 September 1988, the Northern Territory Court of Criminal Appeals unanimously overturned all convictions against Lindy and Michael Chamberlain.[6] The exoneration was based on a rejection of two key points of the prosecution's case and of biased and invalid assumptions made during the initial trial.[citation needed]

The questionable nature of the forensic evidence in the Chamberlain trial, and the weight given to it, raised concerns about such procedures and about expert testimony in criminal cases. The prosecution had successfully argued that the pivotal haemoglobin tests indicated the presence of foetal haemoglobin in the Chamberlains' car and it was a significant factor in the original conviction. But it was later shown that these tests were highly unreliable and that similar tests, conducted on a "sound deadener" sprayed on during the manufacture of the car, had yielded virtually identical results.[citation needed]

Two years after they were exonerated, the Chamberlains were awarded A$1.3 million in compensation for wrongful imprisonment, a sum that covered less than one third of their legal expenses.[19]

The findings of the third coroner's inquest were released on 13 December 1995; and the coroner found that "the cause and manner of death as unknown."[5]

The findings of the fourth coroner's inquest were released on 12 June 2012;[2] and the coroner found that:

ii) Azaria Chamberlain died at Uluru, then known as Ayers Rock, on 17 August 1980. iii) The cause of her death was as the result of being attacked and taken by a dingo.

— Ms Elizabeth Morris SM, Coroner. Inquest into the death of Azaria Chantel Loren Chamberlain [2012] NTMC 020. 12 June 2012.

Media involvement and bias

The Chamberlain trial was the most publicised in Australian history.[3] Given that most of the evidence presented in the case against Lindy Chamberlain was later rejected, the case is now used as an example of how media and bias can adversely affect a trial.[20]

Public and media opinion during the trial was polarised, with "fanciful rumours and sickening jokes" and many cartoons.[21][22] In particular, antagonism was directed towards Lindy Chamberlain for reportedly not behaving as a "stereotypical" grieving mother.[23] Much was made of the Chamberlains' Seventh-day Adventist religion, including false allegations that the church was actually a cult that killed infants as part of bizarre religious ceremonies,[24] that the family took a newborn baby to a remote desert location, and that Lindy Chamberlain showed little emotion during the proceedings.[citation needed]

One anonymous tip was received from a man, falsely claiming to be Azaria's doctor in Mount Isa, that the name "Azaria" meant "sacrifice in the wilderness" (it actually means "God helped").[25] Others claimed that Lindy Chamberlain was a witch.[26]

The press appeared to seize upon any point that could be sensationalised. For example, it was reported that Lindy Chamberlain dressed her baby in a black dress. This provoked negative opinion, despite the trends of the early 1980s, during which black and navy cotton girls' dresses were in fashion, often trimmed with brightly coloured ribbon, or printed with brightly coloured sprigs of flowers.[27][28]

Subsequent events

Since the Chamberlain case, proven cases of attacks on humans by dingoes have been discussed in the public domain, in particular dingo attacks on Fraser Island (off the Queensland coast), the last refuge in Australia for isolated pure-bred wild dingoes. In the wake of these attacks, it emerged that there had been at least 400 documented dingo attacks on Fraser Island. Most were against children, but at least two were on adults.[29] For example, in April 1998, a 13-month-old girl was attacked by a dingo and dragged for about one metre (3 ft) from a picnic blanket at the Waddy Point camping area. The child was dropped when her father intervened.[30]

In July 2004, Frank Cole, a Melbourne pensioner, claimed that he had shot a dingo in 1980 and found a baby in its mouth. After interviewing Cole on the matter, police decided not to reopen the case. He claimed to have the ribbons from the jacket which Azaria had been wearing when she disappeared as proof of his involvement. However, Lindy Chamberlain claimed that the jacket had no ribbons on it.[31] Cole's credibility was further damaged when it was revealed he had made unsubstantiated claims about another case.[32]

In August 2005, a 25-year-old woman named Erin Horsburgh claimed that she was Azaria Chamberlain, but her claims were rejected by the authorities and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Media Watch programme, which stated that none of the reports linking Horsburgh to the Chamberlain case had any substance.[33]

In 2008, the Holden Torana car that was tested for Azaria's blood in the original court case was used in the wedding of Aidan Chamberlain, Azaria's brother, who was six when his sister disappeared. His bride arrived at the ceremony in the car and his father, Michael Chamberlain, said that he was proud the couple had chosen to use the car which was the centrepiece of the case.[34]

Current status

The cause of Azaria Chamberlain's disappearance was determined and announced on 12 June 2012. The Northern Territory coroner officially amended her death certificate to show that the cause of death "was as the result of being attacked and taken by a dingo".[1][2]

The Chamberlains divorced in 1991 and have both remarried. Lindy and her second husband lived for a time in the United States and New Zealand but have since returned to Australia.[citation needed]

The National Museum of Australia has in its collection more than 250 items related to the disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain, which Lindy Chamberlain has helped document. Items include courtroom sketches by artists Jo Darbyshire and Veronica O'Leary,[35] camping equipment, a piece of the dashboard from the Chamberlain family's car, outfits worn by Lindy Chamberlain, the number from her prison door, and the black dress worn by Azaria.[27][36] The National Library of Australia has a small collection of items relating to Azaria, such as her birth detail records and her hospital identification bracelet, as well as a manuscript collection which includes around 20,000 documents including some of the Chamberlain family's correspondence and a large number of letters from the general public.[37]

Media and cultural impact

The story has been the subject of several books, films and television shows, and other publications and accounts. John Bryson's book Evil Angels was published in 1985, and in 1988, Australian film director Fred Schepisi adapted the book into a feature film of the same name (released as A Cry in the Dark outside of Australia and New Zealand).[38] It starred Meryl Streep as Lindy Chamberlain and Sam Neill as Michael Chamberlain. The film gave Streep her eighth Academy Award nomination and her first AFI award. In 2002, Lindy, an opera by Moya Henderson, was produced by Opera Australia at the Sydney Opera House.[23][39] The story was dramatised as a TV miniseries, Through My Eyes (2004), with Miranda Otto and Craig McLachlan as the Chamberlains. This miniseries was based on Lindy Chamberlain's book of the same name.[40]

The incident was transmuted from tragedy to morbid comedy material[41] for American shows such as Seinfeld,[42] Buffy the Vampire Slayer[43] Frasier, Project Runway, Family Guy, Hot in Cleveland, Psych, Modern Family, Mother Tucker and The Simpsons,[44] and "became deeply embedded in American pop culture" with phrases such as "A dingo's got my baby!" serving as "a punchline you probably remember hearing before you knew exactly what a dingo was."[45]

Australian rock band The Paradise Motel released an album commemorating the events of Azaria Chamberlain's life entitled Australian Ghost Story on the 30th anniversary of her death.[46]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Brown, Malcolm (12 June 2012). "After 32 years of speculation, it's finally official: a dingo took Azaria". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Inquest into the death of Azaria Chantel Loren Chamberlain [2012] NTMC 020" (PDF). Coroners Court of the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Government of Australia. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Brian Johnstone (30 October 1982). "All the makings of a classic whodunnit". The Age. Australia. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ Inquest into the Death of Azaria Chamberlain

- ^ a b c d Lowndes, John (13 December 1995). "Inquest into the Death of Azaria Chamberlain" (PDF). Coroners Court of the Northern Territory. Government of Australia. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Reference Under s.433A of the Criminal Code by the Attorney-General for the Northern Territory of Australia of Convictions of Alice Lynne Chamberlain and Michael Leigh Chamberlain No. CA2 of 1988 Courts and Judges – Criminal Law – Statute [1988] NTSC 64 (15 September 1988)". AustLII. 15 September 1988. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Dingo took Azaria Chamberlain, coroner finds". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Rintoul, Stuart (13 June 2012). "'Azaria's spirit can rest'". The Australian. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Brown, Malcolm (18 December 2011). "NT coroner to hold new Azaria inquest 30 years on". The Age. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ "Chamberlain Case (High Court Project)". Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Waterford, Jack (13 June 2012). "No safety from legal lynching". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Hubert, Lawrence; Wainer, Howard (25 September 2012). A Statistical Guide for the Ethically Perplexed. CRC Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4398-7368-7. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ ""A Synopsis of the Identity of the Spray Material on the Dash Support Bracket in the Car of Mr & Ms M L Chamberlain" by L. N. Smith" (PDF). Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b Linder, Douglas O. (2012). "The Trial of Lindy and Michael Chamberlain ("The Dingo Trial"): A Trial Commentary". University of Missouri–Kansas City. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ Harris, Les (December 1980). "Report of Les Harris, Expert on Dingo Behavior, on the Propensity of Dingoes to Attack Humans". University of Missouri–Kansas City. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Re Alice Lynne Chamberlain and Michael Leigh Chamberlain v RE II (29 April 1983)". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Chamberlain v RE II High Court Verdict (22 February 1984)". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Simper, Errol (14 August 2010). "Discovery of jacket vindicated Lindy". The Australian. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Fife-Yeomans, Janet (14 June 2012). "Northern Territory Government apology to Lindy and Michael Chamberlain unlikely". Herald Sun. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Lindy Chamberlain". National Library of Australia. Government of Australia. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ "Prisoners of a nation's prejudices". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 June 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ "The Chamberlain ("Dingo") Trial as Seen by Cartoonists". University of Missouri-Kansas City. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Rock Opera". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 October 2002. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Steel, Fiona. "A Cry in the Night Part 1 of 3". TruTV. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Creswell, Toby; Trenoweth, Samantha (1 January 2006). 1001 Australians You Should Know. Pluto Press Australia. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-86403-361-8. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "A Cry in the Dark". sensesofcinema.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b "The dress that got tongues wagging and split a nation". The Sydney Morning Herald. 7 September 2005. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- ^ "Azaria Chamberlain's dress". National Museum of Australia. Government of Australia. 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ "Fraser Island dingo attack won't affect tourism". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 April 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ "Long history of Fraser dingo attacks". The Age. 30 April 2001. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Close Azaria case for good now: Lindy". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 6 October 2004. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ "Frank Cole makes claims about another murder mystery". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 6 September 2004. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "A dingo ate their ethics". Media Watch. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 September 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Azaria Chamberlain blood car used in brother's wedding". The Daily Telegraph. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Chamberlain trial drawings". National Museum of Australia. Government of Australia. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Conversation with Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton". National Museum of Australia. Government of Australia. 14 October 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Lindy Chamberlain". National Library of Australia. Government of Australia. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "A Cry in the Dark (1988) – Release Info". IMDb. Amazon.com. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Moya Henderson". ABC Radio National. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 October 2002. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Enker, Debi (23 November 2004). "Trial by fury". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ Gorman, James; Kenneally, Christine (5 March 2012). "Australia's Changing View of the Dingo". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Australia asks again: Did a dingo kill the baby?". Newsday. AP. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Tippet, Gary (10 July 2004). "Azaria still a vestige of human frailty". The Age. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Alberti, John (2004). "Ethnic Stereotyping". Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture. Wayne State University Press. p. 280. ISBN 0-8143-2849-0. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Miet, Hannah (12 June 2012). "The Dingo Did, in Fact, Take Her Baby". The Wire. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Quinn, Karl (30 September 2010). "Paradise regained". The Age. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

Bibliography

- Boyd, Guy, ed. (1984). Justice in jeopardy: twelve witnesses speak out. ISBN 0-9591142-0-3.

- Brien, Steve (1984). Azaria: the trial of the century. ISBN 0-7255-1409-4.

- Bryson, John (2000). Evil angels. ISBN 0-7336-1328-4.

- Bryson, John (1997). Le chien du desert rouge (in French). ISBN 2-7427-1271-2.

- Chamberlain Information Service. Azaria newsletter.

- Chamberlain Innocence Committee (1985). New forensic evidence in support of an inquiry into the convictions of M. and L. Chamberlain.

- Crispin, Ken (1987). The crown versus Chamberlain, 1980–1987. ISBN 0-86760-088-8.

- Edmund, Gary (1998). "Negotiating the Meaning of a Scientific Experiment During a Murder Trial and Some Limits to Legal Deconstruction for the Public Understanding of Law and Science". Sydney Law Review. 20 (3): 361.

- Flanigan, Veronica M. (1984). The Azaria evidence: fact or fiction?.

- Lewis, Robert (1990). The Chamberlain case, was justice done?. ISBN 0-646-03087-6.

- Paynter, Tony (1984). Ace lie. ISBN 0-949852-15-5.

- Reynolds, Paul (1989). The Azaria Chamberlain case: reflections on Australian identity. ISBN 1-85507-002-2.

- Richardson, Buck (2002). Dingo innocent: the Azaria Chamberlain mystery. ISBN 0-9577290-0-6.

- Rollo, George W. (1982). The Azaria mystery: a reason to kill.

- Shears, Richard (1982). Azaria. ISBN 0-17-006146-9.

- Simmonds, James (1982). Azaria, Wednesday's child. ISBN 0-9592699-0-8.

- Ward, Phil (1984). Azaria! What the jury were not told. ISBN 0-9591133-0-4.

- Weathered, Lynne (2004). "A question of innocence: Facilitating DNA-based exonerations in Australia". Deakin Law Review.

- Wilson, Belinda. The making of a modern myth: the Chamberlain case and the Australian media (M.A. thesis).

- "Episode 30, 26 September 2005". Mediawatch. 26 September 2005. ABC TV. A dingo ate their ethics.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|began=,|city=,|serieslink=,|ended=, and|seriesno=(help); External link in|transcripturl=|transcripturl=ignored (|transcript-url=suggested) (help)