Deccan painting

Deccan painting or Deccani painting is the form of Indian miniature painting produced in the Deccan region of Central India, in the various Muslim capitals of the Deccan sultanates that emerged from the break-up of the Bahmani Sultanate by 1520. These were Bijapur, Golkonda, Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Berar. The main period was between the late 16th century and the mid-17th, with something of a revival in the mid-18th century, by then centred on Hyderabad.[2][3]

The high quality of early miniatures suggests that there was already a local tradition, probably at least partly of murals, in which artists had trained. Compared to early Mughal painting evolving at the same time to the north,[4] Deccan painting exceeds in "the brilliance of their colour, the sophistication and artistry of their composition, and a general air of decadent luxury".[5] Deccani painting was less interested in realism than the Mughals, instead pursuing "a more inward journey, with mystic and fantastic overtones".[6]

Other differences include painting faces, not very expertly modelled, in three-quarter view, rather than mostly in profile in the Mughal style, and "tall women with small heads" wearing saris. There are many royal portraits, and although they lack the precise likenesses of their Mughal equivalents, they often convey a vivid impression of their rather bulky subjects. Buildings are depicted as "totally flat screen-like panels".[7] The paintings are relatively rare, and few are signed or dated, or indeed inscribed at all; very few names are known compared to the generally well-documented Mughal imperial workshops.[8]

The Muslim rulers of the Deccan, many of them Shia, had their own links with the Persianate world, rather than having to rely on those of the imperial Mughal court.[9] In the same way, contacts through the large textile trade, and nearby Goa, led to some identifiable borrowings from European images, which perhaps had a more general stylistic influence as well. There also appear to have been Hindu artists who moved north to the Deccan after the sultans combined to heavily defeat the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565, and sack the capital, Hampi.[10]

Early period, to 1600

[edit]

Some of the earliest surviving paintings are the twelve illustrations of a manuscript Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi, an epic-style poem on the life of Sultan Hussain Nizam Shah I of Ahmadnagar, leader of the Deccan alliance that defeated the Vijayanagara Empire. The manuscript was commissioned by his widow when she was acting as regent c. 1565–69, and is now in the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal, Pune.[12] Six of the paintings, most unusually for India, show the queen prominently beside her husband, and another a traditional female-centred scene. Most of the portraits of the queen were scratched out or overpainted after her son Murtaza Nizam Shah I rebelled and imprisoned her in 1569.[13]

There are 400–800 illustrations in the Bijapur manuscript Nujum-ul-Ulum (Stars of Science), an astronomical and astrological encyclopaedia of 1570–71, in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.[14]

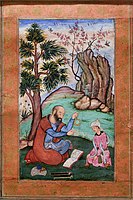

Ragamala paintings, sets illustrating (by evoking their moods) the various raga musical forms, appear to have been an innovation of the Deccan. There is a large dispersed group, probably originally forming several sets, of late sixteenth-century Ragamala paintings, which has been much discussed. They are similar in style, but by several different hands and with a considerable range of quality, with the best "among the most beautiful Indian paintings from any period". They were probably made for Hindu patrons, and may have been produced in a provincial centre well away from the capitals. There were a number of Hindu rajas in the northern Deccan, feudatories of the sultans.[15]

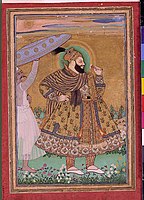

By about 1590 styles at the courts of Ahmadnagar and Bijapur had reached a brilliant maturity,[16] The "decadent fancifulness" of the Lady with the Myna Bird[17] and the young Ibrahim Adil Shah II hawking,[18] both illustrated here, are famous examples of Deccani distinctiveness.

-

Ragamala painting, Hindola Raga, c. 1585. National Museum, New Delhi

-

Scene from the Pune Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi, 1565–69, with the queen later erased. Bharat Itihas Sanshodhak Mandal

-

Lady with the Myna Bird, Golconda or Bijapur, c. 1605, Chester Beatty Library.[19]

-

A Composite Elephant Ridden by a Prince, c. 1600, LACMA

-

Ibrahim Adil Shah II riding his favourite elephant Atash Khan, Bijapur, c. 1600.[20] Private collection

-

Young Prince and Mentor, c. 1600. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Differences between the Mughal and Deccani styles

[edit]Deccan Paintings were not recognised as a separate school of painting and are considered in Persian and Indo-Persian genre, however in 1926 Edgar Blochat started the discussion when he presented to the world a portrait of Sultan of Ahmadnagar from 1526 with very few recognised parallel examples.[21] First, as compared to Mughal miniatures, Deccan painting exceeds in "the brilliance of their colour, the sophistication and artistry of their composition, and a general air of decadent luxury".[22]

Second, Deccani painting was less interested in realism than the Mughals, instead pursuing "a more inward journey, with mystic and fantastic overtones".[23] In Mughal paintings, court scenes, historical events and hunting expeditions are a common occurrence whereas the subjects of Deccan paintings are concentrated on leisure and are of laidback nature as seen in portrait of a prince dozing under a tree, fanned and massaged by pages, displayed in the Islamisches Museum, Berlin (GDR) (85 and col. pl. x1m1). The portraits of Mughal School are shown in more realistic light and in case of Deccan portraits "a gently lyrical atmosphere, often one of quiet abandon to the joys of love, music, poetry or just the perfume of a flower" is depicted. Another reason why the Deccan paintings are confused with Mughal or Rajasthani school because the paintings are relatively rare, and few are signed or dated, or indeed inscribed at all; very few names are known compared to the generally well-documented Mughal imperial workshops.[24]

Schools of Deccan painting

[edit]Three distinct schools of painting emerged from the Deccan Sultanates, those of Bijapur, Golconda and Ahmadnagar.

Bijapur School

[edit]

The Bijapur style of painting mostly developed during the reign of Ali Adil Shah I (r. 1558–1580) and his successor Ibrahim II (r. 1580–1627), both were great patrons of art and music.[25] The root of the style was in Persian culture which was significantly influenced by Hindu culture. The Persian style prevalent in the Deccan was from the early Safavid period when the colouring palette of the Timurid school was prevalent and the Hindu influence was drawn from the South Indian tradition of the land. These cultural impacts impart Bijapur painting its distinct baroque character. Visually the paintings in the Bijapur style are defined by full curved figures adorned with rich jewelry, this also represents the luxurious character of the Adil Shahi court. The main subjects of the style were palaces and gardens, providing it an exotic visual appeal at the first glance. Another prominent character of the particular style is the long muslin dresses and the pointed turbans.[26]

Ahmednagar School

[edit]Paintings from the school of Ahmadnagar are rare as compared to the other styles because the state remained independent for the shortest period of time. Paintings available from the school are great examples possessing "gentle emotion and brilliant colors" inspired from 14th century Italian painting, and similarly both the styles have fondness for plain gold backgrounds. The style also has the energy of Turkman paintings from 15th century, apart from different influences the style has "Indian humanism, an interest in the mass and rhythms of the human body". Most prominents and earliest available series of paintings from the school are twelve illustrations to the history of the reign of Husain Nizam Shah I, written by Aftabi, entitled the Tarif-i husain shahi. Notable and unorthodox character of the series is seen in the portrayal of woman as the queen appears in six of the twelve illustrations.[27]

Golconda School

[edit]

Golconda school also has very few paintings available as the royal collections were thoroughly destroyed when the Mughals conquered the state. In comparison to other Deccan Sultanates, Golconda school maintained a heterogeneous style along with the influences from the Ottoman miniatures, Persian miniatures, Mughal miniatures and Bijapur schools. "Most Golconda work, regardless of its original source, has a tense opulence that is quite different from the poignant romanticism of Bijapur or the refined dignity of Ahmadnagar portraiture. Ornament and figural compositions have a dense, almost pulsating vitality that is fundamentally un-Persian." The paintings have strong rhythm which are a representation of Indian classical dance found on the heavily carved temple facades, thus, there is a strong influence of both Hindu and Persian culture. One of the most illustrated example of Golconda school is Kulliyat of Muhammad Quli's poetry displayed in Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad, considering the level of detailing and intricacies depicted in the artworks of the Manuscript, it can be said that the copy belonged to Sultan himself.[28]

Subjects and style

[edit]

Beside the usual portraits and illustrations to literary works, there are sometimes illustrated chronicles, such as the Tuzuk-i-Asafiya. A Deccan speciality (also sometimes found in other media, such as ivory)[30] is the "composite animal" a large animal made up of many smaller images of other animals. A composite Buraq and an elephant are illustrated here. Rulers are often given large haloes, following Mughal precedent. Servants fan their masters or mistresses with cloths, rather than the chowris or peacock-feather fans seen elsewhere,[31] and swords usually have the straight Deccan form.[32]

Elephants were very popular in both the life and art of the Deccani courts, and artists revelled in depicting them behaving badly during the periodic musth hormonal overloads affecting bull elephants.[33] There was also a genre of drawings with some colour using marbling effects in the bodies of horses and elephants.[34] Apart from elephants, studies of animals or plants were less common in the Deccan than in Mughal painting, and when they occur they often have a less realistic style, with a "fanciful palette of intense colors".[35]

Unusually for India, there was a significant imported population of Africans in the Deccan, a few of whom rose to high positions as soldiers, ministers or courtiers. Malik Ambar of Ahmadnagar and Ikhlas Khan of Bijapur were the most famous of these; a number of portraits survive of both, as well as others of unidentified figures.[36]

One of the most important patrons of the style was Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur (d. 1627), himself a very accomplished painter, as well as a musician and poet. He died the same year as Jahangir, the last Mughal emperor to be an enthusiastic patron of painting other than imperial portraits.[37] The portrait from c. 1590 illustrated above, which comes from the same period as Akbar's artists at the Mughal court were developing the Mughal portrait style, shows a confident but very different style. The extreme close-up view was to remain most unusual in Indian portraiture, and it has been suggested it was directly influenced by European prints, especially those of Lucas Cranach the Elder, with which it shares a number of features.[38]

-

Radha and Krishna Embracing, from a Gita Govinda, Aurangabad (?), c. 1650

-

Finch, Poppies, Dragonfly, and Bee, Deccan, c. 1650–1670, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Brooklyn Museum.

-

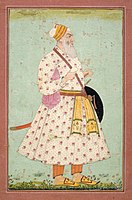

Abul Hasan Qutb Shah, the last Sultan of Golconda, 1670s; he was then imprisoned for 13 years to his death in 1699. San Diego Museum of Art

-

Aurangzeb's general at the siege of Golconda, Ghazi ud-Din Khan Feroze Jung I, Hyderabad, 1690. His son was the first Nizam of Hyderabad

-

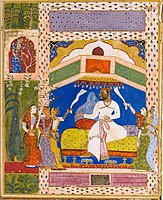

Muhammad Adil Shah (d. 1656) with courtiers and attendants, painted over a century after his death.

Influence

[edit]

The Mughal court was aware of the Deccan style, and some Deccani paintings, especially from Bijapur, were included in albums compiled by Akbar and Jahangir. Some Mughal painters adopted a quasi-Deccani style in the early 17th century, perhaps following instructions from their patrons.[39] Ibrahim Adil Shah II married his daughter, rather reluctantly, to Prince Daniyal Mirza, son of Akbar, and the wedding gifts included volumes of paintings.[40] Several Rajput princes were generals in the Mughal armies fighting in the Deccan, leading to Deccan influences on early Rajput painting. In many cases Deccani painters probably migrated to the Rajput courts as their main patrons fell from power.[41]

Decline

[edit]Deccani painting flourished in the late 16th and 17th centuries but suffered as the Mughals gradually conquered the region, and had already largely adopted a sub-Mughal style by around 1650. Berar Sultanate was absorbed by Ahmadnagar by 1574, and Bidar Sultanate was taken over by Bijapur in 1619; their contributions to the style, whether before or after conquest, are rather uncertain. The city of Ahmadnagar itself was taken by the Mughals in 1600, after the death of the regent-princess Chand Bibi (often portrayed after her death), but part of the territory continued an embattled independence until 1636, with Paranda as the capital until 1610, then the new city later renamed as Aurangabad. The extinction in 1687 of the last two remaining sultanates of Bijapur and Golkonda, both ruled by the Qutb Shahi dynasty, was a decisive blow. Most of both royal collections were destroyed in the conquest, which deprived painters of remaining in the area of models to study.[42]

A new "hybrid Rajasthani-Deccani school of painting" developed in Aurangabad, which became the Mughal capital of the Deccan. One dispersed ragamala set, and a Gita Govinda set in an identical style, were long regarded as Rajasthani until another manuscript in the style emerged, which was inscribed to record that it was painted in Aurangabad in 1650 for a patron from Mewar in Rajasthan; probably the painters were originally from there too.[43]

Mughal viceroys established a court at Hyderabad, but this did not become a centre for miniatures until the next century, by then in a less distinctive late Mughal or post-Mughal style. By now paintings were not just produced for a small court circle, and markets had developed for types including sets of Ragamala paintings, erotic subjects, and Hindu ones.[44] Copies or imitations of old works such as royal portraits continued to be produced well into the 19th century.[45]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Crill and Jariwala, 110

- ^ Harle, 400; Craven, 216–217; Chakraverty, 69; Sardar

- ^ Zebrowski, Mark (1983). Deccani Painting. Sotheby Publications. ISBN 9780520048782.

- ^ Craven, 216

- ^ Harle, 400

- ^ Kossak, 15

- ^ Harle, 400–403 (quoted); Craven 216–217

- ^ Chakraverty, 70

- ^ Sardar; Chakraverty, 72; Deccan Style paintings at the Wayback Machine (archived 1 December 2016)

- ^ Harle, 403–405; Craven, 216–217; Chakraverty, 69

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 169

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 145–147; Craven, 216; Chakraverty, 70

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 145–147

- ^ Sardar; [slamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;EPM;ir;Mus21;40;en Chester Beatty page]; Michell and Zebrowski, 160–162

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 153–157, 154 quoted; Harle, 401–403

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 151, 162–168; Harle, 400

- ^ Harle, 400

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 169

- ^ Harle, 400

- ^ Metropolitan Museum page

- ^ Zebrowski, Mark (1983). Deccani painting. Roli Books International, New Delhi.

- ^ Harle, 400

- ^ Kossak, 15

- ^ Chakraverty, 70

- ^ BINNEY, EDWIN (1979). "INDIAN PAINTINGS FROM THE DECCAN". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 127 (5280): 784–804. ISSN 0035-9114.

- ^ Gray, Basil (1938). "Deccani Paintings: The School of Bijapur". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 73 (425): 74–77. ISSN 0951-0788.

- ^ Zebrowski, Mark (1983). Deccani painting. Roli Books International, New Delhi.

- ^ Zebrowski, Mark (1983). Deccani painting. Roli Books International, New Delhi.

- ^ "Nauras: The Many Arts of the Deccan". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Born, Wolfgang, "Ivory Powder Flasks from the Mughal Period", Ars Islamica, Vol. 9, (1942), pp. 93–111, Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan, JSTOR

- ^ Harle, 401

- ^ Harle, 405

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 151

- ^ Kossak, 68; Marbled elephant

- ^ "Finch, Poppies, Dragonfly, and Bee", Brooklyn Museum

- ^ Crill and Jariwala, 110, 116; Harle, 403

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 162–164; Craven, 217; Sardar; Crill and Jariwala, 110

- ^ Crill and Jariwala, 110

- ^ Chakraverty, 70

- ^ Chakraverty, 71

- ^ Crill and Jariwala, 34; Chakraverty, 73; Harle, 395

- ^ Chakraverty, 73; Kossak, 68

- ^ Michell and Zebrowski, 157–158

- ^ Harle, 405–406

- ^ Chakraverty, 73

References

[edit]- Chakraverty, Anjan, Indian Miniature Painting, 2005, Lustre Press, ISBN 8174363343, 9788174363343

- Craven, Roy C., Indian Art: A Concise History, 1987, Thames & Hudson (Praeger in USA), ISBN 0500201463

- Crill, Rosemary, and Jariwala, Kapil. The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2010, ISBN 9781855144095

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Kossak, Steven. (1997). Indian court painting, 16th–19th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-783-1

- Michell, George, and Zebrowski, Mark, Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, Volume 1 (The New Cambridge History of India, vol 7), 1999, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521563216, 9780521563215, google books

- Sardar, Marika. "Islamic Art of the Deccan". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Navina Najat Haidar, Marika Sardar, Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy, 2015, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 9780300211108, 0300211104, google books

- Zebrowski, Mark, Deccani Painting, University of California Press, 1983.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training: The history of Deccani Painting

![Lady with the Myna Bird, Golconda or Bijapur, c. 1605, Chester Beatty Library.[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Yogini_with_a_Mynah_Bird%2C_by_the_Dublin_Painter._Bijapur%2C_early_17th_century%2C_44x32cm%2C_Chester_Beatty_Library%2C_Dublin_%28cropped%29.jpg/126px-Yogini_with_a_Mynah_Bird%2C_by_the_Dublin_Painter._Bijapur%2C_early_17th_century%2C_44x32cm%2C_Chester_Beatty_Library%2C_Dublin_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Ibrahim Adil Shah II riding his favourite elephant Atash Khan, Bijapur, c. 1600.[20] Private collection](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Sultan_Ibrahim_Adil_Shah_II_Riding_His_Prized_Elephant%2C_Atash_Khan.jpg/158px-Sultan_Ibrahim_Adil_Shah_II_Riding_His_Prized_Elephant%2C_Atash_Khan.jpg)