Destruction of opium at Humen

| Destruction of opium at Humen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 虎門銷菸 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 虎门销烟 | ||||||

| |||||||

The destruction of opium at Humen began on 3 June 1839 and involved the destruction of 1,000 long tons (1,016 t) of illegal opium seized from British traders under the aegis of Lin Zexu, an Imperial Commissioner of Qing China. Conducted on the banks of the Pearl River outside Humen Town, Dongguan, China, the action provided casus belli for Great Britain to declare war on Qing China.[1] What followed is now known as the First Opium War (1839–1842), a conflict that initiated China's opening for trade with foreign nations under a series of treaties with the western powers.

Background

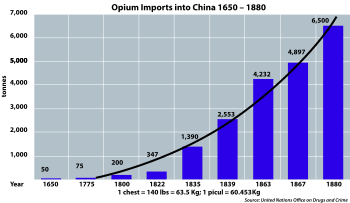

A reduction in import duty by the British government on Chinese tea from 110 per cent to an average ten per cent in 1784 caused a surge in domestic demand, which in turn led to a huge silver deficit for the East India Company (EIC), who were the sole importers of the commodity.[2] Silver was the only currency the Chinese would accept in payment for their tea and to redress the balance in 1793 the EIC acquired a monopoly on opium production in India from the British government. However, as it had been illegal to sell the drug in China since 1800,[3] consignments were sent to Calcutta for auction[4] whereafter private traders smuggled the opium to the southern ports of mainland China.[4][5]

In 1834 the EIC lost its trading monopoly in China[6] and instead Queen Victoria appointed Lord Napier as first commissioner of trade for the country. Napier's first visit to the southern port of Canton (now Guangzhou), where the rigid Canton System controlled all trade with China, failed to convince the Chinese authorities to open up further ports for trading. In 1837, the Qing government, having vacillated for a while on the correct approach to the problem of growing opium addiction amongst the people, decided to expel merchant William Jardine of Jardine, Matheson & Co along with others involved in the illegal trade. Governor-General of Guangdong and Guangxi Deng Tingzhen and the governor of Guangdong along with the Guangdong Customs Supervisor (粵海关部监督) issued an edict to this effect[7] although Jardine remained in the country. Former Royal Navy officer Charles Elliot became Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China in 1838, by which time the number of Chinese opium addicts had grown to between four and twelve million.[8] Although some officials argued that a tax on opium would yield a profit for the imperial treasury, the Daoguang Emperor instead decided to stop the trade altogether and severely punish those involved. He then appointed respected scholar and government official Lin Zexu as Special Imperial Commissioner to enforce his will.

Lin and the foreign traders

"Any foreigner or foreigners bringing opium to the Central Land, with design to sell the same, the principals shall most assuredly be decapitated, and the accessories strangled; and all property (found on board the same ship) shall be confiscated. The space of a year and a half is granted, within the which, if any one bringing opium by mistake, shall voluntarily step forward and deliver it up, he shall be absolved from all consequences of his crime."

Soon after his arrival in Canton in the middle of 1838, Lin wrote to Queen Victoria in an appeal to her moral responsibility to stop the opium trade.[9] The letter elicited no response (sources suggest that it was lost in transit),[10] but it was later reprinted in the London Times as a direct appeal to the British public. An edict from the Daoguang Emperor followed on 18 March,[11] emphasising the serious penalties for opium smuggling that would now apply.

On 18 March 1839, Lin summoned the twelve Chinese merchants of the Cohong who acted as intermediaries for the foreign opium traders. He told them that all European merchants were to hand over the opium in their possession and cease trading in the drug forthwith.[11] The commissioner went on to call the Cohong "traitors" and accuse them of complicity in the illegal trade; they had three days to persuade the foreigners to forfeit their opium or two of them would be executed and their wealth and lands confiscated. Howqua, the leader of the Cohong passed Lin's orders to the foreign merchants who subsequently convened a meeting of their Chamber of Commerce on 21 March. After the meeting, Howqua was told that Lin's move was a bluff and his threats should be ignored. In fear for his life, the merchant then suggested that surrendering at least some contraband might assuage Lin. Lancelot Dent of Dent & Co. agreed to surrender a small quantity of the drug and others followed suit, even though the amounts offered represented only a tiny fraction of the foreign merchants' total stock, which was worth millions of pounds.[12] The commissioner then backed down on his promise to execute members of the Cohong and instead invited the top foreign merchants including Dent[13] to his residence for interview. Without considering the potential repercussions and with Jardine gone from Canton, Lin decided to behead Dent as an example to the other traders and force them to hand over all their opium. Dent was warned by his friends[14] that in 1774 an individual who had heeded such a summons ended up garroted[15] so he instead asked Howqua to tell Lin he would meet him provided he received a guarantee of safe conduct. Dent further stalled by sending Robert Inglis, one of his partners, to a meeting with Lin's subordinates. Charles Elliot then ordered all British ships in Canton to head for the safety of Hong Kong island before he himself arrived at the foreign factories on 24 March, 1839, three days after the expiry of Lin's deadline. After raising the Union Jack, the British superintendent of trade announced that all foreign merchants were henceforth under the protection of the British government.[16] Chinese soldiers then sealed off access to the factory area and began a campaign to intimidate the foreign residents trapped inside. Elliot read out a petition stating that all opium was to be handed over, promising compensation from the British government for the costs of the merchandise, with a deadline of six pm on 27 March. By nightfall, British traders had agreed to surrender around 20,000 chests of opium (approximately 1,300 long tons (1,321 t))[5] with a value of 2,000,000 British pounds.[17] Even though Lin believed that the British had surrendered all their supplies, the factories remained in a state of virtual siege as the commissioner demanded that the Americans, the French, the Indians and the Dutch hand over a further 20,000 chests in total.[18] This would have been impossible; the French were absent from Canton at the time, the Indians and Americans claimed that any opium they held belonged to others while the Dutch did not deal in the drug.

Destruction of the opium

"At an elevated spot on the shore a space was barricaded in; here a pit was dug, and filled with opium mixed with brine: into this, again, lime was thrown, forming a scalding furnace, which made a kind of boiling soup of the opium. In the evening the mixture was let out by sluices, and allowed to flow out to sea with the ebb tide."

Lin's initial plan called for the transport of the seized opium under Chinese guard to Lankit Island (Longxue Island), some 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Bogue forts and 35 miles (56 km) from Canton. However, he agreed that men assigned by Elliot could instead carry out the task.[20] Deng Tingzhen together with Lin arrived at the Bogue on 11 April. According to a Chinese account of events, at this point Lin offered three catties[A] of tea for every one of opium surrendered.[21] The Jardine Matheson clippers Austin and Hercules moored in the river and began the transfer of opium in their holds but rough waters forced them to relocate to Chuanbi Island further down river and close to the Shajiao Fort (沙角炮台) outside Humen Town. By 21 May 1839, 20,283 chests had been unloaded at Chuanbi. Pleased with the outcome, Daogguang sent Lin a roebuck venison to symbolise an imminent promotion and a hand-written scroll inscribed with the Chinese characters for good luck and long life.[22] On 24 May, all foreign merchants previously involved in the opium trade received orders from Lin to leave China forever. They departed in a flotilla under the command of Charles Elliot, who by now had become persona non grata with the British government for his acquiescence to Chinese demands.

Lin then set about destroying the seized opium. After encircling the site with a bamboo fence to prevent theft, three stone pits, lined with wood, were dug into which was poured the seized opium along with lime and salt. A minor interruption occurred when one man was caught trying to remove a quantity of the drug—he was beheaded on the spot.[23] Once the pits had been filled with sea water, labourers tramped the mixture to ensure the drug's destruction. The residue was then flushed through a channel into the South China Sea while Lin said a prayer apologising for the pollution. The work commenced on 3 June 1839 and took a total of 23 days [24] When the task was finished, the American missionary, Elijah Coleman Bridgman, who witnessed events, commented: "The degree of care and fidelity, with which the whole work was conducted, far exceeded our expectations ..."[25]

Aftermath

Once the opium had been destroyed, Elliot promised the merchants compensation for their losses from the British government. However, the country's parliament had never agreed to such an offer, and instead thought that it was the Chinese government's responsibility to pay reparations to the merchants. Frustrated that any repayment for the destroyed opium seemed unlikely, the merchants turned to William Jardine, who had left Canton just prior to Lin’s arrival. Jardine believed that open warfare was the only way to force compensation from the Qing authorities and in London he began a campaign to sway the British government,[26] meeting with Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston in October 1839. The following March, in the face of strong opposition from, among others, the Chartists, the pro-war lobby eventually won 271 to 262 in a House of Commons debate on whether to despatch a naval force to China.[27] In the spring of 1840 an expeditionary force of sixteen warships and 31 other ships left India for China,[26] which would become involved in multiple Sino-British battles in the First Opium War that followed.

Legacy

The "Lin Zuxu Memorial" to commemorate destruction of the opium opened outside Humen in 1957 and in 1972 was renamed "Anti-British Memorial for Humen People of the Opium War." It later became the "Opium War Museum" with additional responsibility for administration of the ruins of the Shajiao and Weiyuan Batteries. A further "Sea Battle Museum" on the site opened to the public in December 1999.[28]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Zhang 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Ebrey 2010, p. 236.

- ^ a b Alexander 1856, p. 11.

- ^ a b United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Policy Analysis and Research Branch 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Newbould 1990, p. 111.

- ^ Canton Free Press, 14 February 1837; reprinted in The Times (London), 31 March 1837

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Teng & Fairbank 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 41.

- ^ a b Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 43.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Ouchterlony 1844, p. 13.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Boswell, James (1785). "Affairs of the East Indies". The Scots Magazine. 47. Edinburgh: Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran: 355.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Melancon, Glenn (1999), "Honor in Opium? The British Declaration of War on China, 1839-1840", International History Review, 21 (4): 859

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Parker & Wei 1888, p. 6-7.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Parker & Wei 1888, p. 6.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Tamura 1997, p. 98.

- ^ "China Commemorates Anti-opium Hero". 4 June 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ The Chinese Repository. VIII: 74. 1840.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Ebrey (2010), p. 239. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEEbrey2010239" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Beeching 1975, p. 111.

- ^ "The Opium War Museum". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Bibliography

- Alexander, Robert (1856). The Rise and Progress of British Opium Smuggling: The Illegality of the East India Company's Monopoly of the Drug, and Its Injurious Effects Upon India, China, and the Commerce of Great Britain. Five Letters Addressed to the Earl of Shaftesbury. London: Judd and Glass.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Beeching, Jack (1975). The Chinese Opium Wars. Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091227302.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, ed. (2010). "9. Manchus and Imperialism: The Qing Dynasty 1644–1900". The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hanes, W. Travis; Sanello, Frank (2002). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402201493.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Newbould, Ian (1990). Whiggery and Reform, 1830-41: The Politics of Government. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804717595.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War: An Account of All the Operations of the British Forces from the Commencement to the Treaty of Nanking. London: Saunders and Otley.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Parker, Edward Harper; Wei, Yuan (1888). 聖武記. The Pagoda Library. Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|title=at position 1 (help)

- Tamura, Eileen H. (1997). Chapter 2; Civilizations in Collision: China in Transition, 1750–1920. China: Understanding Its Past. Vol. 1. Curriculum Research & Development Group, University of Hawaii and University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824819231.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Teng, Ssu-yu; Fairbank, John King (1979). China's Response to the West: A Documentary Survey, 1839-1923. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674120259.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Policy Analysis and Research Branch (2010). A Century of International Drug Control. Bulletin on Narcotics. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. ISBN 9789211482454.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Wright, David (2000). Translating Science: The Transmission of Western Chemistry Into Late Imperial China, 1840-1900. Sinica Leidensia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004117761.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Zhang, Weibin (2006). Hong Kong: The Pearl Made of British Mastery and Chinese Docile-diligence. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 9781594546006.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)