Donskoy Monastery

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

| |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Orthodox |

| Established | 1591 |

| Disestablished | 1918 |

| Reestablished | 1992 |

| Diocese | Moscow |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Feodor I of Russia |

| Site | |

| Location | Moscow, Russia |

| Coordinates | 55°42′52″N 37°36′7.5″E / 55.71444°N 37.602083°E |

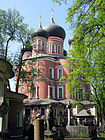

Donskoy Monastery (Russian: Донско́й монасты́рь) is a major monastery in Moscow, founded in 1591[1] in commemoration of Moscow's deliverance from the threat of an invasion by the Crimean Khan Kazy-Girey. Commanding a highway to the Crimea, the monastery was intended to defend southern approaches to the Moscow Kremlin.

History

[edit]Muscovite period

[edit]

The monastery was built on the spot where Boris Godunov's mobile fortress and Sergii Radonezhsky's field church with Theophan the Greek's icon Our Lady of the Don had been located. Legend has it that Dmitry Donskoy had taken this icon with him to the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. The Tatars left without a fight and were defeated during their retreat.

Initially, the cloister was rather poor and numbered only a few monks. As of 1629, the Donskoy Monastery possessed 20 wastelands and 16 peasant households (20 peasants altogether). In 1612, it was taken for one day by the Polish-Lithuanian commander Jan Karol Chodkiewicz. In 1618, the Battle of Donskoy Monastery took place between Russian Cavalry and Ukrainian Cossacks of Petro Konashevych, which ended in Cossack victory.

In the mid-17th century the monastery was attached to the Andreyevsky Monastery. In 1678, however, its independence was reinstated and the cloister received rich donations, including more than 1,400 peasant households. In 1683, the Donskoy Monastery was elevated to the archmandrite level and given 20 desyatinas of the nearby pasturelands. Vidogoshchsky, Zhizdrinsky, Sharovkin, and Zheleznoborovsky monasteries were attached to the Donskoy Monastery[2] between 1683 and 1685.

Imperial period

[edit]Since 1711, the Great Cathedral's vault was used for burials of Georgian tsarevichs of the Bagrationi family and Mingrelian dukes of the Dadiani family.

In 1724, the monks and the property of the Andreyevsky Monastery were transferred to the Donskoy Monastery. By 1739, it had already possessed 880 households with 6,716 peasants, 14 windmills, and a few fisheries. In 1747, the authorities wanted to transfer the Slavic Greek Latin Academy to the Donskoy Monastery, but the cloister confined itself to paying salaries to the academic staff from its own treasury.

Archbishop Ambrose (Zertis-Kamensky) was killed within the monastery walls during the Plague Riot in 1771. In 1812, the French army ransacked the Donskoy Monastery,[3] the most valuable things having been moved to Vologda prior to that. There had been 48 monks and 2 novices in the monastery by 1917.

Soviet period and beyond

[edit]

After the October Revolution, the Donskoy Monastery was closed. In 1922–1925, Patriarch Tikhon was detained in this cloister after his arrest. He chose to remain in this monastery after his release. Saint Tikhon's relics were discovered following his canonization in 1989. They are exhibited for veneration in the Great Cathedral in summer and in the Old Cathedral in winter.

The Soviet authorities moved remnants of many monasteries and cathedrals they had destroyed or used for other purposes to the Donskoy Monastery. The items came from various places in the Soviet capital: the dynamited Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the Church of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker in Stolpy, the Church of the Assumption on Pokrovka Street, the Sukharev Tower, and others.

In 1924, some of the facilities of the Donskoy Monastery were occupied by a penal colony for children. A more notorious use was the unmarked burial of those shot and cremated by the secret police between 1934 and the 1950s. Only after 1985 were such unmarked burials remains finally marked.[4]

After the collapse of communism and the establishment of the Russian Federation, the Monastery was returned to the Russian Orthodox Church in 1992. Over the next ten years full lists were finally compiled of those buried in the monastery graveyard and other locations in and around the Russian capital.[5]

Architecture

[edit]When the monastery was established, Boris Godunov personally laid the foundation stone of its cathedral, consecrated in 1593 to the holy image of Our Lady of the Don. This diminutive structure, quite typical for Godunov's reign, has a single dome crowning three tiers of zakomara. In the 1670s, they added two symmetrical annexes, and a refectory leading to a tented belltower. Its iconostasis, executed in 1662, formerly adorned one of Moscow churches demolished by the Communists. From 1930 to 1946, the cathedral was closed for services and housed a factory.

The New (or the Great) Cathedral, also dedicated to the Virgin of the Don, was started in 1684 as a votive church of Tsarevna Sophia Alekseyevna. After she fell into disgrace, its construction was funded by private donations. The masons and artisans were invited from Ukraine, which explains some of the cathedral's unusual features. For the first time in Moscow, the five domes were arranged according to the four corners of the Earth (as was the Ukrainian custom). The Old Believers felt offended by this and called the cathedral "Antichrist's Altar". Eight tiers of its ornate baroque iconostasis were carved by Kremlin masters in 1688–1698. The iconostasis' central piece is a copy of the Virgin of the Don, as painted in the mid-16th century. The cathedral frescoes are the first in Moscow to be painted by a foreigner. They were executed by Antonio Claudio in 1782–1785.

After the monastery lost its defensive importance, its walls were reshaped in the red-and-white Muscovite baroque style, reminiscent of the Novodevichy Convent. Eight square and four circular towers with red-blood crowns were put up in 1686–1711. The Holy Gates of the monastery (1693) are topped with the Tikhvin church (1713–1714), noted for its wrought iron grille. A lofty belfry was erected over the western gates from 1730–1753 after designs sometimes attributed to Pietro Antonio Trezzini.

Necropolis

[edit]

Several families of high aristocracy chose the Donskoy monastery as location of their burial vaults. The Alexander Svirsky Church, for instance, was constructed in 1796–1798 as a sepulchre of Princes Zubov. Princes Galitzine were buried in the Archangel Church (1714–1809), whereas the Church of St. John Chrysostom (1881–1891) marks the Pervushin family vault.

The old necropolis in the south-eastern part of the monastery is remarkable for its ornate tombs, executed by some of the best Russian sculptors. They mark the graves of the poets Mikhail Kheraskov and Alexander Sumarokov, the philosophers Pyotr Chaadaev and Ivan Ilyin, the historians Mikhail Shcherbatov and Vasily Klyuchevsky, the critic Vladimir Odoyevsky, the architect Osip Bove, the painter Vasily Perov, the courtier Alexander Dmitriev-Mamonov, the notorious murderer Daria Saltykova, and the aviator Nikolay Zhukovsky. Tikhon of Moscow is interred underneath the old katholikon. Some of the tombs were transferred by Soviet authorities to the Shchusev Museum of Architecture, where no one can see them now.

Since no Communists were buried in the old necropolis inside the monastery, the relatives of some notable Russian Whites decided to move their remains from foreign cemeteries to the Donskoy Monastery. Among the notable people reburied in this way are Ivan Shmelyov (2000), Vladimir Kappel (2007), Anton Denikin (2005), and Ivan Ilyin (2005). Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn also asked to be buried there, rather than at the Novodevichy Cemetery, with its Communist associations.

A large new necropolis was inaugurated in 2010 just outside the monastery walls. It contains three mass graves of the cremated ashes of executed political prisoners from Joseph Stalin's Great Purge. See New Donskoy Cemetery for details.

References

[edit]- ^ "Донской-Богородицкий монастырь". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron (in Russian). Vol. 11 (Домиции — Евреинова). 1893.

- ^ "Donskoy Monastery ➔ Orthodox Monastery in Moscow ✮ Russia 2019". www.moscovery.com. September 23, 2016. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Донской монастырь (in Russian). XPOHOC. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ "MOSCOW Donskoe graveyard [C]* Burials & Cremations". mapofmemory.org. August 19, 2014.

- ^ Lists of those shot in Moscow 1937-1952: The Donskoe cemetery [crematorium], edited and compiled by Seleznyov, Yeremina, and Roginsky, Memorial: Moscow, 2005 (596 pp).

External links

[edit] Media related to Donskoy Monastery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Donskoy Monastery at Wikimedia Commons- Official website (in Russian)

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1591

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1714

- Monasteries in Moscow

- Eastern Orthodox cemeteries in Russia

- Russian Orthodox monasteries in Russia

- Baroque architecture in Russia

- 1591 establishments in Russia

- Religious organizations established in the 1590s

- Christian monasteries established in the 16th century

- Burial sites of the House of Mukhrani

- Burial sites of Russian noble families

- Burial sites of the Gediminids

- Cultural heritage monuments of federal significance in Moscow