Dragon King

| Dragon King | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

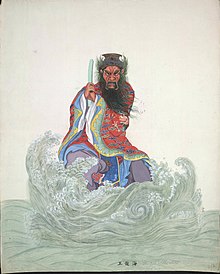

The Dragon King of the Four Seas, painted in the first half of the 19th century. | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍王 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙王 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Dragon King Dragon Prince | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍神 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Dragon God | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Long vương | ||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 龍王 | ||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

The Dragon King, also known as the Dragon God, is a Chinese water and weather god. He is regarded as the dispenser of rain as well as the zoomorphic representation of the yang masculine power of generation.[1] He is the collective personification of the ancient concept of the lóng in Chinese culture. He can take a variety of forms, the most important ones being the cosmological Sìhǎi Lóngwáng (四海龍王 "Dragon Kings of the Four Seas")[2] who, with the addition of the Yellow Dragon (黃龍 Huánglóng) of Xuanyuan, represent the watery and chthonic forces presided over by the Five Forms of the Highest Deity (五方上帝 Wǔfāng Shàngdì), or their zoomorphic incarnation. One of his epithets is Dragon King of Wells and Springs.[3] The dragon king is the king of the dragons and he also controls all of the creatures in the sea. The dragon king gets his orders from the Jade Emperor.

Besides being a water deity, the Dragon God frequently also serves as a territorial tutelary deity, similarly to Tudigong and Houtu.[4]

Yellow Dragon

The Yellow Dragon (黃龍 Huánglóng) does not have a precise body of water of which he is the patron. However, as the zoomorphic incarnation of the Yellow Emperor, he represents the source of the myriad things.[5]

Dragon Kings of the Four Seas

Each one of the four Dragon Kings of the Four Seas (四海龍王 Sìhǎi Lóngwáng) is associated to a colour and a body of water corresponding to one of the four cardinal directions and natural boundaries of China:[1] the East Sea (corresponding to the East China Sea), the South Sea (corresponding to the South China Sea), the West Sea (Qinghai Lake), and the North Sea (Lake Baikal). They appear in the classical novels like The Investiture of the Gods and Journey to the West. Each of them has a proper name, and they share the surname Ao (敖, meaning "playing" or "proud").

Azure Dragon

The Azure Dragon or Blue-Green Dragon (青龍 Qīnglóng), or Green Dragon (蒼龍 Cānglóng), is the Dragon God of the east, and of the essence of spring.[1] His proper name is Ao Guang (敖廣), and he is the patron of the East China Sea.

Red Dragon

The Red Dragon (赤龍 Chìlóng or 朱龍 Zhūlóng, literally "Cinnabar Dragon", "Vermilion Dragon") is the Dragon God of the south and of the essence of summer.[1] He is the patron of the South China Sea and his proper name is Ao Qin (敖欽).

White Dragon

The White Dragon (白龍 Báilóng) is the Dragon God of the west and the essence of autumn.[1] His proper names are Ao Run (敖閏), Ao Jun (敖君) or Ao Ji (敖吉). He is the patron of Qinghai Lake.

Black Dragon

The Black Dragon (黑龍 Hēilóng), also called "Dark Dragon" or "Mysterious Dragon" (玄龍 Xuánlóng), is the Dragon God of the north and the essence of winter.[1] His proper names are Ao Shun (敖順) or Ao Ming (敖明), and his body of water is Lake Baikal.

Worship of the Dragon God

Worship of the Dragon God is celebrated throughout China with sacrifices and processions during the fifth and sixth moons, and especially on the date of his birthday the thirteenth day of the sixth moon.[1] A folk religious movement of associations of good-doing in modern Hebei is primarily devoted to a generic Dragon God whose icon is a tablet with his name inscribed, for which it has been named the "movement of the Dragon Tablet".[6]

Artistic depictions

- Longwang in art

-

The Dragon King part of a statue representing "Takenouchi no Sukune Meeting the Dragon King of the Sea", dated 1875–1879, Japan.

-

Dragon King sculpture with residual traces of pigment, dated 11th–12th century, Japan.

-

The Dragon Kings of the Four Seas at the Great Temple of Mazu in Tainan.

-

The four Dragon Kings at the Temple of Mazu in Anping, Tainan.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Tom (1989), p. 55.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 20: "[...] Dragon Kings of the Four Seas, Five Lakes, Eight Rivers and Nine Streams (in sum, the lord of all the waters) [...]".

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 21.

- ^ Nikaido (2015), p. 54.

- ^ Fowler (2005), pp. 200–201.

- ^ Zhiya Hua. Dragon's Name: A Folk Religion in a Village in South-Central Hebei Province. Shanghai People's Publishing House, 2013. ISBN 7208113297

Sources

- Fowler, Jeanine D. (2005). An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1845190866.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nikaido, Yoshihiro (2015). Asian Folk Religion and Cultural Interaction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3847004859.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Overmyer, Daniel L. (2009). Local Religion in North China in the Twentieth Century the Structure and Organization of Community Rituals and Beliefs (PDF). Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789047429364.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824812859.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

![]() Media related to Dragon King at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dragon King at Wikimedia Commons