Drug discovery

In the fields of medicine, biotechnology and pharmacology, drug discovery is the process by which new candidate medications are discovered. Historically, drugs were discovered through identifying the active ingredient from traditional remedies or by serendipitous discovery. Later chemical libraries of synthetic small molecules, natural products or extracts were screened in intact cells or whole organisms to identify substances that have a desirable therapeutic effect in a process known as classical pharmacology. Since sequencing of the human genome which allowed rapid cloning and synthesis of large quantities of purified proteins, it has become common practice to use high throughput screening of large compounds libraries against isolated biological targets which are hypothesized to be disease modifying in a process known as reverse pharmacology. Hits from these screens are then tested in cells and then in animals for efficacy.

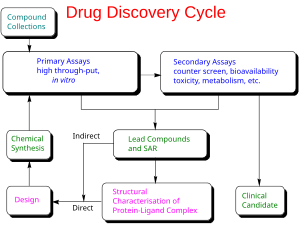

Modern drug discovery involves the identification of screening hits, medicinal chemistry and optimization of those hits to increase the affinity, selectivity (to reduce the potential of side effects), efficacy/potency, metabolic stability (to increase the half-life), and oral bioavailability. Once a compound that fulfills all of these requirements has been identified, it will begin the process of drug development prior to clinical trials. One or more of these steps may, but not necessarily, involve computer-aided drug design. Modern drug discovery is thus usually a capital-intensive process that involves large investments by pharmaceutical industry corporations as well as national governments (who provide grants and loan guarantees). Despite advances in technology and understanding of biological systems, drug discovery is still a lengthy, "expensive, difficult, and inefficient process" with low rate of new therapeutic discovery.[1] In 2010, the research and development cost of each new molecular entity (NME) was approximately US$1.8 billion.[2] Drug discovery is done by pharmaceutical companies, with research assistance from universities. The "final product" of drug discovery is a patent on the potential drug. The drug requires very expensive Phase I, II and III clinical trials, and most of them fail. Small companies have a critical role, often then selling the rights to larger companies that have the resources to run the clinical trials.

Discovering drugs that may be a commercial success, or a public health success, involves a complex interaction between investors, industry, academia, patent laws, regulatory exclusivity, marketing and the need to balance secrecy with communication.[3] Meanwhile, for disorders whose rarity means that no large commercial success or public health effect can be expected, the orphan drug funding process ensures that people who experience those disorders can have some hope of pharmacotherapeutic advances.

Historical background

The idea that the effect of a drug in the human body is mediated by specific interactions of the drug molecule with biological macromolecules, (proteins or nucleic acids in most cases) led scientists to the conclusion that individual chemicals are required for the biological activity of the drug. This made for the beginning of the modern era in pharmacology, as pure chemicals, instead of crude extracts, became the standard drugs. Examples of drug compounds isolated from crude preparations are morphine, the active agent in opium, and digoxin, a heart stimulant originating from Digitalis lanata. Organic chemistry also led to the synthesis of many of the natural products isolated from biological sources.

Historically substances, whether crude extracts or purified chemicals were screened for biological activity without knowledge of the biological target. Only after an active substance was identified was an effort made to identify the target. This approach is known as classical pharmacology, forward pharmacology,[4] or phenotypic drug discovery.[5]

Later, small molecules were synthesized to specifically target a known physiological/pathological pathway, rather than adopt the mass screening of banks of stored compounds. This led to great success, such as the work of Gertrude Elion and George H. Hitchings on purine metabolism,[6][7] the work of James Black[8] on beta blockers and cimetidine, and the discovery of statins by Akira Endo.[9] Another champion of the approach of developing chemical analogues of known active substances was Sir David Jack at Allen and Hanbury's, later Glaxo, who pioneered the first inhaled selective beta2-adrenergic agonist for asthma, the first inhaled steroid for asthma, ranitidine as a successor to cimetidine, and supported the development of the triptans.[10]

Gertrude Elion, working mostly with a group of fewer than 50 people on purine analogues, contributed to the discovery of the first anti-viral; the first immunosuppressant (azathioprine) that allowed human organ transplantation; the first drug to induce remission of childhood leukaemia; pivotal anti-cancer treatments; an anti-malarial; an anti-bacterial; and a treatment for gout.

Cloning of human proteins made possible the screening of large libraries of compounds against specific targets thought to be linked to specific diseases. This approach is known as reverse pharmacology and is the most frequently used approach today.[11]

Drug targets

The definition of "target" itself is something argued within the pharmaceutical industry. Generally, the "target" is the naturally existing cellular or molecular structure involved in the pathology of interest that the drug-in-development is meant to act on. However, the distinction between a "new" and "established" target can be made without a full understanding of just what a "target" is. This distinction is typically made by pharmaceutical companies engaged in discovery and development of therapeutics. In an estimate from 2011, 435 human genome products were identified as therapeutic drug targets of FDA-approved drugs.[12]

"Established targets" are those for which there is a good scientific understanding, supported by a lengthy publication history, of both how the target functions in normal physiology and how it is involved in human pathology. This does not imply that the mechanism of action of drugs that are thought to act through a particular established target is fully understood. Rather, "established" relates directly to the amount of background information available on a target, in particular functional information. The more such information is available, the less investment is (generally) required to develop a therapeutic directed against the target. The process of gathering such functional information is called "target validation" in pharmaceutical industry parlance. Established targets also include those that the pharmaceutical industry has had experience mounting drug discovery campaigns against in the past; such a history provides information on the chemical feasibility of developing a small molecular therapeutic against the target and can provide licensing opportunities and freedom-to-operate indicators with respect to small-molecule therapeutic candidates.

In general, "new targets" are all those targets that are not "established targets" but which have been or are the subject of drug discovery campaigns. These typically include newly discovered proteins, or proteins whose function has now become clear as a result of basic scientific research.

The majority of targets currently selected for drug discovery efforts are proteins. Two classes predominate: G-protein-coupled receptors (or GPCRs) and protein kinases.

Screening and design

The process of finding a new drug against a chosen target for a particular disease usually involves high-throughput screening (HTS), wherein large libraries of chemicals are tested for their ability to modify the target. For example, if the target is a novel GPCR, compounds will be screened for their ability to inhibit or stimulate that receptor (see antagonist and agonist): if the target is a protein kinase, the chemicals will be tested for their ability to inhibit that kinase.

Another important function of HTS is to show how selective the compounds are for the chosen target. The ideal is to find a molecule which will interfere with only the chosen target, but not other, related targets. To this end, other screening runs will be made to see whether the "hits" against the chosen target will interfere with other related targets - this is the process of cross-screening. Cross-screening is important, because the more unrelated targets a compound hits, the more likely that off-target toxicity will occur with that compound once it reaches the clinic.

It is very unlikely that a perfect drug candidate will emerge from these early screening runs. It is more often observed that several compounds are found to have some degree of activity, and if these compounds share common chemical features, one or more pharmacophores can then be developed. At this point, medicinal chemists will attempt to use structure-activity relationships (SAR) to improve certain features of the lead compound:

- increase activity against the chosen target

- reduce activity against unrelated targets

- improve the druglikeness or ADME properties of the molecule.

This process will require several iterative screening runs, during which, it is hoped, the properties of the new molecular entities will improve, and allow the favoured compounds to go forward to in vitro and in vivo testing for activity in the disease model of choice.

Amongst the physico-chemical properties associated with drug absorption include ionization (pKa), and solubility; permeability can be determined by PAMPA and Caco-2. PAMPA is attractive as an early screen due to the low consumption of drug and the low cost compared to tests such as Caco-2, gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and Blood–brain barrier (BBB) with which there is a high correlation.

A range of parameters can be used to assess the quality of a compound, or a series of compounds, as proposed in the Lipinski's Rule of Five. Such parameters include calculated properties such as cLogP to estimate lipophilicity, molecular weight, polar surface area and measured properties, such as potency, in-vitro measurement of enzymatic clearance etc. Some descriptors such as ligand efficiency[13] (LE) and lipophilic efficiency[14][15] (LiPE) combine such parameters to assess druglikeness.

While HTS is a commonly used method for novel drug discovery, it is not the only method. It is often possible to start from a molecule which already has some of the desired properties. Such a molecule might be extracted from a natural product or even be a drug on the market which could be improved upon (so-called "me too" drugs). Other methods, such as virtual high throughput screening, where screening is done using computer-generated models and attempting to "dock" virtual libraries to a target, are also often used.

Another important method for drug discovery is de novo drug design, in which a prediction is made of the sorts of chemicals that might (e.g.) fit into an active site of the target enzyme. For example, virtual screening and computer-aided drug design are often used to identify new chemical moieties that may interact with a target protein.[16][17] Molecular modelling[18] and molecular dynamics simulations can be used as a guide to improve the potency and properties of new drug leads.[19][20]

There is also a paradigm shift in the drug discovery community to shift away from HTS, which is expensive and may only cover limited chemical space, to the screening of smaller libraries (maximum a few thousand compounds). These include fragment-based lead discovery (FBDD)[21][22][23][24] and protein-directed dynamic combinatorial chemistry.[25][26][27][28][29] The ligands in these approaches are usually much smaller, and they bind to the target protein with weaker binding affinity than those hits that are identified from HTS. Further modified through organic synthesis into lead compounds are often required. Such modifications are often guided by protein X-ray crystallography of the protein-fragment complex.[30][31][32] The advantages of these approaches are that they allow more efficient screening and the compound library, although small, typically covers a large chemical space when compared to HTS.

Once a lead compound series has been established with sufficient target potency and selectivity and favourable drug-like properties, one or two compounds will then be proposed for drug development. The best of these is generally called the lead compound, while the other will be designated as the "backup".

Nature as source of drugs

Traditionally many drugs and other chemicals with biological activity have been discovered by studying allelopathy - chemicals that organisms create that affect the activity of other organisms in the fight for survival.[33]

Despite the rise of combinatorial chemistry as an integral part of lead discovery process, natural products still play a major role as starting material for drug discovery.[34] A 2007 report[35] found that of the 974 small molecule new chemical entities developed between 1981 and 2006, 63% were natural derived or semisynthetic derivatives of natural products. For certain therapy areas, such as antimicrobials, antineoplastics, antihypertensive and anti-inflammatory drugs, the numbers were higher. In many cases, these products have been used traditionally for many years.

Natural products may be useful as a source of novel chemical structures for modern techniques of development of antibacterial therapies.[36]

Despite the implied potential, only a fraction of Earth’s living species has been tested for bioactivity.

Plant-derived

Prior to Paracelsus, the vast majority of traditionally used crude drugs in Western medicine were plant-derived extracts. This has resulted in a pool of information about the potential of plant species as an important source of starting material for drug discovery. A different set of metabolites is sometimes produced in the different anatomical parts of the plant (e.g. root, leaves and flower), and botanical knowledge is crucial also for the correct identification of bioactive plant materials.

Microbial metabolites

Microbes compete for living space and nutrients. To survive in these conditions, many microbes have developed abilities to prevent competing species from proliferating. Microbes are the main source of antimicrobial drugs. Streptomyces species have been a valuable source of antibiotics. The classical example of an antibiotic discovered as a defense mechanism against another microbe is the discovery of penicillin in bacterial cultures contaminated by Penicillium fungi in 1928.

Marine invertebrates

Marine environments are potential sources for new bioactive agents.[37] Arabinose nucleosides discovered from marine invertebrates in 1950s, demonstrating for the first time that sugar moieties other than ribose and deoxyribose can yield bioactive nucleoside structures. However, it was 2004 when the first marine-derived drug was approved. The cone snail toxin ziconotide, also known as Prialt, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat severe neuropathic pain. Several other marine-derived agents are now in clinical trials for indications such as cancer, anti-inflammatory use and pain. One class of these agents are bryostatin-like compounds, under investigation as anti-cancer therapy.

Chemical diversity of natural products

As above mentioned, combinatorial chemistry was a key technology enabling the efficient generation of large screening libraries for the needs of high-throughput screening. However, now, after two decades of combinatorial chemistry, it has been pointed out that despite the increased efficiency in chemical synthesis, no increase in lead or drug candidates has been reached.[35] This has led to analysis of chemical characteristics of combinatorial chemistry products, compared to existing drugs or natural products. The chemoinformatics concept chemical diversity, depicted as distribution of compounds in the chemical space based on their physicochemical characteristics, is often used to describe the difference between the combinatorial chemistry libraries and natural products. The synthetic, combinatorial library compounds seem to cover only a limited and quite uniform chemical space, whereas existing drugs and particularly natural products, exhibit much greater chemical diversity, distributing more evenly to the chemical space.[34] The most prominent differences between natural products and compounds in combinatorial chemistry libraries is the number of chiral centers (much higher in natural compounds), structure rigidity (higher in natural compounds) and number of aromatic moieties (higher in combinatorial chemistry libraries). Other chemical differences between these two groups include the nature of heteroatoms (O and N enriched in natural products, and S and halogen atoms more often present in synthetic compounds), as well as level of non-aromatic unsaturation (higher in natural products). As both structure rigidity and chirality are both well-established factors in medicinal chemistry known to enhance compounds specificity and efficacy as a drug, it has been suggested that natural products compare favourable to today's combinatorial chemistry libraries as potential lead molecules.

Natural product drug discovery

Screening

Two main approaches exist for the finding of new bioactive chemical entities from natural sources.

The first is sometimes referred to as random collection and screening of material, but in fact the collection is often far from random in that biological (often botanical) knowledge is used about which families show promise, based on a number of factors, including past screening. This approach is based on the fact that only a small part of earth’s biodiversity has ever been tested for pharmaceutical activity. It is also based on the fact that organisms living in a species-rich environment need to evolve defensive and competitive mechanisms to survive, mechanisms which might usefully be exploited in the development of drugs that can cure diseases affecting humans. A collection of plant, animal and microbial samples from rich ecosystems can potentially give rise to novel biological activities worth exploiting in the drug development process. One example of a successful use of this strategy is the screening for antitumour agents by the National Cancer Institute, started in the 1960s. Paclitaxel was identified from Pacific yew tree Taxus brevifolia. Paclitaxel showed anti-tumour activity by a previously undescribed mechanism (stabilization of microtubules) and is now approved for clinical use for the treatment of lung, breast and ovarian cancer, as well as for Kaposi's sarcoma. Early in the 21st century, Cabazitaxel (made by Sanofi, a French firm), another relative of taxol has been shown effective against prostate cancer, also because it works by preventing the formation of microtubules, which pull the chromosomes apart in dividing cells (such as cancer cells). Still another examples are: 1. Camptotheca (Camptothecin · Topotecan · Irinotecan · Rubitecan · Belotecan); 2. Podophyllum (Etoposide · Teniposide); 3a. Anthracyclines (Aclarubicin · Daunorubicin · Doxorubicin · Epirubicin · Idarubicin · Amrubicin · Pirarubicin · Valrubicin · Zorubicin); 3b. Anthracenediones (Mitoxantrone · Pixantrone).

Nor do all drugs developed in this manner come from plants. Professor Louise Rollins-Smith of Vanderbilt University's Medical Center, for example, has developed from the skin of frogs a compound which blocks AIDS. Professor Rollins-Smith is aware of declining amphibian populations and has said: "We need to protect these species long enough for us to understand their medicinal cabinet."

The second main approach involves Ethnobotany, the study of the general use of plants in society, and ethnopharmacology, an area inside ethnobotany, which is focused specifically on medicinal uses.

Both of these two main approaches can be used in selecting starting materials for future drugs. Artemisinin, an antimalarial agent from sweet wormtree Artemisia annua, used in Chinese medicine since 200BC is one drug used as part of combination therapy for multiresistant Plasmodium falciparum.

Structural elucidation

The elucidation of the chemical structure is critical to avoid the re-discovery of a chemical agent that is already known for its structure and chemical activity. Mass spectrometry is a method in which individual compounds are identified based on their mass/charge ratio, after ionization. Chemical compounds exist in nature as mixtures, so the combination of liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is often used to separate the individual chemicals. Databases of mass spectras for known compounds are available, and can be used to assign a structure to an unknown mass spectrum. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is the primary technique for determining chemical structures of natural products. NMR yields information about individual hydrogen and carbon atoms in the structure, allowing detailed reconstruction of the molecule’s architecture.

See also

References

- ^ Anson D, Ma J, He JQ (1 May 2009). "Identifying Cardiotoxic Compounds". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. TechNote. Vol. 29, no. 9. Mary Ann Liebert. pp. 34–35. ISSN 1935-472X. OCLC 77706455. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, Schacht AL (March 2010). "How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry's grand challenge". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 9 (3): 203–14. doi:10.1038/nrd3078. PMID 20168317.

- ^ Warren J (April 2011). "Drug discovery: lessons from evolution". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 71 (4): 497–503. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03854.x. PMC 3080636. PMID 21395642.

- ^ Takenaka T (September 2001). "Classical vs reverse pharmacology in drug discovery". BJU International. 88 Suppl 2: 7–10, discussion 49–50. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2001.00112.x. PMID 11589663.

- ^ Lee JA, Uhlik MT, Moxham CM, Tomandl D, Sall DJ (May 2012). "Modern phenotypic drug discovery is a viable, neoclassic pharma strategy". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 55 (10): 4527–38. doi:10.1021/jm201649s. PMID 22409666.

- ^ Elion GB (1993). "The quest for a cure". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 33: 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000245. PMID 8494337.

- ^ Elion GB. "The purine path to chemotherapy. Nobel Lecture 1988".

- ^ Black J. "Drugs from emasculated hormones: the principles of synoptic antagonism. Nobel Lecture 1988". Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Endo A. "The discovery of the statins and their development". Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Watts G (2012). "Obituary: Sir David Jack" (PDF). The Lancet. 379 (9811): 116. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60053-1.

- ^ Swinney DC, Anthony J (July 2011). "How were new medicines discovered?". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 10 (7): 507–19. doi:10.1038/nrd3480. PMID 21701501.

- ^ Rask-Andersen M, Almén MS, Schiöth HB (August 2011). "Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 10 (8): 579–90. doi:10.1038/nrd3478. PMID 21804595.

- ^ Hopkins AL, Groom CR, Alex A (May 2004). "Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection". Drug Discovery Today. 9 (10): 430–1. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. PMID 15109945.

- ^ Ryckmans T, Edwards MP, Horne VA, Correia AM, Owen DR, Thompson LR, Tran I, Tutt MF, Young T (August 2009). "Rapid assessment of a novel series of selective CB(2) agonists using parallel synthesis protocols: A Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) analysis". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 19 (15): 4406–9. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.062. PMID 19500981.

- ^ Leeson PD, Springthorpe B (November 2007). "The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 6 (11): 881–90. doi:10.1038/nrd2445. PMID 17971784.

- ^ Rester U (July 2008). "From virtuality to reality - Virtual screening in lead discovery and lead optimization: a medicinal chemistry perspective". Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development. 11 (4): 559–68. PMID 18600572.

- ^ Rollinger JM, Stuppner H, Langer T (2008). "Virtual screening for the discovery of bioactive natural products". Progress in Drug Research. Progress in Drug Research. 65 (211): 211, 213–49. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8117-2_6. ISBN 978-3-7643-8098-4. PMID 18084917.

- ^ Barcellos GB, Pauli I, Caceres RA, Timmers LF, Dias R, de Azevedo WF (December 2008). "Molecular modeling as a tool for drug discovery". Current Drug Targets. 9 (12): 1084–91. doi:10.2174/138945008786949388. PMID 19128219.

- ^ Durrant JD, McCammon JA (Oct 2011). "Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery". BMC Biology. 9: 71. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-9-71. PMC 3203851. PMID 22035460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Borhani DW, Shaw DE (January 2012). "The future of molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 26 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1007/s10822-011-9517-y. PMC 3268975. PMID 22183577.

- ^ Erlanson DA, McDowell RS, O'Brien T (July 2004). "Fragment-based drug discovery". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (14): 3463–82. doi:10.1021/jm040031v. PMID 15214773.

- ^ Folkers G, Jahnke W, Erlanson DA, Mannhold R, Kubinyi H (2006). Fragment-based Approaches in Drug Discovery (Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-31291-9.

- ^ Erlanson DA (June 2011). "Introduction to fragment-based drug discovery". Topics in Current Chemistry. 317: 1–32. doi:10.1007/128_2011_180. PMID 21695633.

- ^ Zartler, Edward; Shapiro, Michael (2008). Fragment-based drug discovery a practical approach. Wiley.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Greaney MF, Bhat VT (2010). "Chapter 2: Protein-directed dynamic combinatorial chemistry". In Miller BL (ed.). Dynamic combinatorial chemistry: in drug discovery, bioinorganic chemistry, and materials sciences. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 43–82.

- ^ Huang R, Leung IK (Jul 2016). "Protein-directed dynamic combinatorial chemistry: a guide to protein ligand and inhibitor discovery". Molecules. 21 (7): 910. doi:10.3390/molecules21070910. PMID 27438816.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mondal M, Hirsch AK (April 2015). "Dynamic combinatorial chemistry: a tool to facilitate the identification of inhibitors for protein targets". Chemical Society Reviews. 44 (8): 2455–88. doi:10.1039/c4cs00493k. PMID 25706945.

- ^ Herrmann A (March 2014). "Dynamic combinatorial/covalent chemistry: a tool to read, generate and modulate the bioactivity of compounds and compound mixtures". Chemical Society Reviews. 43 (6): 1899–933. doi:10.1039/c3cs60336a. PMID 24296754.

- ^ Jahnke W, Erlanson DA, eds. (2006). "Chapter 16: Dynamic combinatorial diversity in drug discovery". Fragment-based approaches in drug discovery. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 341–364.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Caliandro R, Belviso DB, Aresta BM, de Candia M, Altomare CD (June 2013). "Protein crystallography and fragment-based drug design". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 5 (10): 1121–40. doi:10.4155/fmc.13.84. PMID 23795969.

- ^ Chilingaryan Z, Yin Z, Oakley AJ (Oct 2012). "Fragment-based screening by protein crystallography: successes and pitfalls". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (10): 12857–79. doi:10.3390/ijms131012857. PMC 3497300. PMID 23202926.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Valade A, Urban D, Beau JM (Jan–Feb 2007). "Two galactosyltransferases' selection of different binders from the same uridine-based dynamic combinatorial library". Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry. 9 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1021/cc060033w. PMID 17206823.

- ^ Roger, Manuel Joaquín Reigosa; Reigosa, Manuel J.; Pedrol, Nuria; González, Luís (2006), Allelopathy: a physiological process with ecological implications, Springer, p. 1, ISBN 1-4020-4279-5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Feher M, Schmidt JM (2003). "Property distributions: differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry". Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 43 (1): 218–27. doi:10.1021/ci0200467. PMID 12546556.

- ^ a b Newman DJ, Cragg GM (March 2007). "Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years". Journal of Natural Products. 70 (3): 461–77. doi:10.1021/np068054v. PMID 17309302.

- ^ von Nussbaum F, Brands M, Hinzen B, Weigand S, Häbich D (August 2006). "Antibacterial natural products in medicinal chemistry--exodus or revival?". Angewandte Chemie. 45 (31): 5072–129. doi:10.1002/anie.200600350. PMID 16881035.

The handling of natural products is cumbersome, requiring nonstandardized workflows and extended timelines. Revisiting natural products with modern chemistry and target-finding tools from biology (reversed genomics) is one option for their revival.

- ^ John Faulkner D, Newman DJ, Cragg GM (February 2004). "Investigations of the marine flora and fauna of the Islands of Palau". Natural Product Reports. 21 (1): 50–76. doi:10.1039/b300664f. PMID 15039835.

Further reading

- Gad SC (2005). Drug Discovery Handbook. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience/J. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-21384-5.

- Madsen U, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Liljefors T (2002). Textbook of Drug Design and Discovery. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-28288-8.

- Rasmussen, Nicolas (2014). Gene Jockeys: Life Science and the rise of Biotech Enterprise. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-42141-340-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)