Edgar Degas: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 92.16.52.125 (talk) to last version by DARTH SIDIOUS 2 |

Tag: references removed |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

he liked cheese burgers |

|||

Degas was born in [[Paris]], France, the eldest of five children of Célestine Musson De Gas and Augustin De Gas, a [[bank]]er. The family was moderately wealthy. His mother died when Degas was thirteen, after which his father and grandfather were the main influences on his early life. At age eleven, Degas (in adulthood he abandoned the more pretentious spelling of the family name)<ref>The family's ancestral name was Degas. Jean Sutherland Boggs explains that De Gas was the spelling, "with some pretentions, used by the artist's father when he moved to Paris to establish a French branch of his father's Neopolitan bank." While Edgar Degas's brother René adopted the still more aristocratic de Gas, the artist reverted to the original spelling, Degas, by age thirty. Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 98.</ref> began his schooling with enrollment in the [[Lycée Louis-le-Grand]], graduating in 1853 with a ''baccalauréat'' in literature. |

|||

Degas was born in [[Paris]], France, the t age eleven, Degas (in adulthood he abandoned the more pretentious spelling of the family name)<ref>The family's ancestral name was Degas. Jean Sutherland Boggs explains that De Gat'' in literature. |

|||

Degas began to paint early in his life. By eighteen, he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio, and in 1853 he registered as a copyist in the [[Louvre]]. His father, however, expected him to go to [[law school]]. Degas duly registered at the Faculty of Law of the [[University of Paris]] in November 1853, but made little effort at his studies there. In 1855, Degas met [[Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres]], whom he revered, and whose advice he never forgot: "Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist."<ref>Werner 1969, p. 14</ref> In April of that same year, Degas received admission to the [[École des Beaux-Arts]], where he studied drawing with [[Louis Lamothe]], under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Ingres.<ref>Canaday 1969, p. 930-931</ref> In July 1856, Degas traveled to [[Italy]], where he would remain for the next three years. In 1858, while staying with his aunt's family in [[Naples]], he made the first studies for his early masterpiece, ''[[The Bellelli Family]]''. He also drew and painted copies after [[Michelangelo]], [[Raphael]], [[Titian]], and other artists of the [[Renaissance]], often selecting from an altarpiece an individual head which he treated as a portrait.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 154</ref> By 1860 Degas had made more than seven hundred{{Citation needed|date=April 2009}} copies of works including Italian Renaissance and French Classical art. |

Degas began to paint early in his life. By eighteen, he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio, and in 1853 he registered as a copyist in the [[Louvre]]. His father, however, expected him to go to [[law school]]. Degas duly registered at the Faculty of Law of the [[University of Paris]] in November 1853, but made little effort at his studies there. In 1855, Degas met [[Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres]], whom he revered, and whose advice he never forgot: "Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist."<ref>Werner 1969, p. 14</ref> In April of that same year, Degas received admission to the [[École des Beaux-Arts]], where he studied drawing with [[Louis Lamothe]], under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Ingres.<ref>Canaday 1969, p. 930-931</ref> In July 1856, Degas traveled to [[Italy]], where he would remain for the next three years. In 1858, while staying with his aunt's family in [[Naples]], he made the first studies for his early masterpiece, ''[[The Bellelli Family]]''. He also drew and painted copies after [[Michelangelo]], [[Raphael]], [[Titian]], and other artists of the [[Renaissance]], often selecting from an altarpiece an individual head which he treated as a portrait.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 154</ref> By 1860 Degas had made more than seven hundred{{Citation needed|date=April 2009}} copies of works including Italian Renaissance and French Classical art. |

||

Revision as of 20:39, 14 September 2010

Edgar Degas | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait (Degas au porte-fusain), 1855 | |

| Born | Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting, Sculpture, Drawing |

| Notable work | The Bellelli Family (1858-1867) Woman with Chrysanthemums (1865) Chanteuse de Café (c.1878) At the Milliner's (1882) |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Signature | |

| |

Edgar Degas[p] (19 July 1834 – 27 September 1917), born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (French pronunciation: [ilɛʁ ʒɛʁmɛnɛdɡɑʁ dəˈɡɑ]), was a French artist famous for his work in painting, sculpture, printmaking and drawing. He is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism although he rejected the term, and preferred to be called a realist.[1] A superb draughtsman, he is especially identified with the subject of the dance, and over half his works depict dancers. These display his mastery in the depiction of movement, as do his racecourse subjects and female nudes. His portraits are notable for their psychological complexity and depiction of human isolation.[2]

Early in his career, his ambition was to be a history painter, a calling for which he was well prepared by his rigorous academic training and close study of classic art. In his early thirties, he changed course, and by bringing the traditional methods of a history painter to bear on contemporary subject matter, he became a classical painter of modern life.[3]

Early life

he liked cheese burgers

Degas was born in Paris, France, the t age eleven, Degas (in adulthood he abandoned the more pretentious spelling of the family name)Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). In April of that same year, Degas received admission to the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied drawing with Louis Lamothe, under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Ingres.[4] In July 1856, Degas traveled to Italy, where he would remain for the next three years. In 1858, while staying with his aunt's family in Naples, he made the first studies for his early masterpiece, The Bellelli Family. He also drew and painted copies after Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, and other artists of the Renaissance, often selecting from an altarpiece an individual head which he treated as a portrait.[5] By 1860 Degas had made more than seven hundred[citation needed] copies of works including Italian Renaissance and French Classical art.

Artistic career

Upon his return to France in 1859, Degas moved into a Paris studio large enough to permit him to begin painting The Bellelli Family—an imposing canvas he intended for exhibition in the Salon, although it remained unfinished until 1867. He also began work on several history paintings: Alexander and Bucephalus and The Daughter of Jephthah in 1859–60; Sémiramis Building Babylon in 1860; and Young Spartans around 1860.[6] In 1861, Degas visited his childhood friend Paul Valpinçon in Normandy, and made the earliest of his many studies of horses. He exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1865, when the jury accepted his painting Scene of War in the Middle Ages, which attracted little attention.[7] Although he exhibited annually in the Salon during the next five years, he submitted no more history paintings, and his Steeplechase—The Fallen Jockey (Salon of 1866) signaled his growing commitment to contemporary subject matter. The change in his art was influenced primarily by the example of Édouard Manet, whom Degas had met in 1864 (while both were copying the same Velázquez portrait in the Louvre, according to a story that may be apocryphal).[8]

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Degas enlisted in the National Guard, where his defense of Paris left him little time for painting. During rifle training his eyesight was found to be defective, and for the rest of his life his eye problems were a constant worry to him.[9]

After the war, in 1872, Degas began an extended stay in New Orleans, Louisiana, where his brother René and a number of other relatives lived. Staying in a house on Esplanade Avenue, Degas produced a number of works, many depicting family members. One of Degas' New Orleans works, depicting a scene at The Cotton Exchange at New Orleans, garnered favorable attention back in France, and was his only work purchased by a museum (that of Pau) during his lifetime.

Degas returned to Paris in 1873. The following year his father died, and in the subsequent settling of the estate it was discovered that Degas' brother René had amassed enormous business debts. To preserve the family name, Degas was forced to sell his house and a collection of art he had inherited. Dependent for the first time in his life on sales of his artwork for income, he produced much of his greatest work during the decade beginning in 1874.[10] By now thoroughly disenchanted with the Salon, Degas joined forces with a group of young artists who were intent upon organizing an independent exhibiting society. The first of their exhibitions, which were quickly dubbed Impressionist Exhibitions, was in 1874. The Impressionists subsequently held seven additional shows, the last in 1886. Degas took a leading role in organizing the exhibitions, and showed his work in all but one of them, despite his persistent conflicts with others in the group. He had little in common with Monet and the other landscape painters, whom he mocked for painting outdoors. Conservative in his social attitudes, he abhorred the scandal created by the exhibitions, as well as the publicity and advertising that his colleagues sought.[1] He bitterly rejected the label Impressionist that the press had created and popularized, and his insistence on including non-Impressionist artists such as Jean-Louis Forain and Jean-François Raffaëlli in their exhibitions created rancor within the group, contributing to their eventual disbanding in 1886.[11]

As his financial situation improved through sales of his own work, he was able to indulge his passion for collecting works by artists he admired: old masters such as El Greco and such contemporaries as Manet, Pissarro, Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh. Three artists he idolized, Ingres, Delacroix, and Daumier, were especially well represented in his collection.[12]

In the late 1880s, Degas also developed a passion for photography.[13] He photographed many of his friends, often by lamplight, as in his double portrait of Renoir and Mallarmê. Other photographs, depicting dancers and nudes, were used for reference in some of Degas' drawings and paintings.[14]

As the years passed, Degas became isolated, due in part to his belief that a painter could have no personal life.[15] The Dreyfus Affair controversy brought his anti-Semitic leanings to the fore and he broke with all his Jewish friends.[16] His argumentative nature was deplored by Renoir, who said of him: "What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn't stay till the end."[17]

Although he is known to have been working in pastel as late as the end of 1907, and is believed to have continued making sculpture as late as 1910, he apparently ceased working in 1912, when the impending demolition of his longtime residence on the rue Victor Massé forced a wrenching move to quarters on the boulevard de Clichy.[18] He never married and spent the last years of his life, nearly blind, restlessly wandering the streets of Paris[19] before dying in 1917.

Artistic style

Degas is often identified as an Impressionist, an understandable but insufficient description. Impressionism originated in the 1860s and 1870s and grew, in part, from the realism of such painters as Courbet and Corot. The Impressionists painted the realities of the world around them using bright, "dazzling" colors, concentrating primarily on the effects of light, and hoping to infuse their scenes with immediacy.

Technically, Degas differs from the Impressionists in that he "never adopted the Impressionist color fleck",[20] and he continually belittled their practice of painting en plein air.[21] "He was often as anti-impressionist as the critics who reviewed the shows", according to art historian Carol Armstrong; as Degas himself explained, "no art was ever less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and of the study of the great masters; of inspiration, spontaneity, temperament, I know nothing."[22] Nonetheless, he is described more accurately as an Impressionist than as a member of any other movement. His scenes of Parisian life, his off-center compositions, his experiments with color and form, and his friendship with several key Impressionist artists—most notably Mary Cassatt and Édouard Manet—all relate him intimately to the Impressionist movement.[23]

Degas' style reflects his deep respect for the old masters (he was an enthusiastic copyist well into middle age)[24] and his great admiration for Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. He was also a collector of Japanese prints, whose compositional principles influenced his work, as did the vigorous realism of popular illustrators such as Daumier and Gavarni. Although famous for horses and dancers, Degas began with conventional historical paintings such as The Young Spartans, in which his gradual progress toward a less idealized treatment of the figure is already apparent. During his early career, Degas also painted portraits of individuals and groups; an example of the latter is The Bellelli Family (c.1858–67), a brilliantly composed and psychologically poignant portrayal of his aunt, her husband, and their children. In this painting, as in The Young Spartans and many later works, Degas was drawn to the tensions present between men and women. In his early paintings, Degas already evidenced the mature style that he would later develop more fully by cropping subjects awkwardly and by choosing unusual viewpoints.

By the late 1860s, Degas had shifted from his initial forays into history painting to an original observation of contemporary life. Racecourse scenes provided an opportunity to depict horses and their riders in a modern context. He began to paint women at work, milliners and laundresses. Mlle. Fiocre in the Ballet La Source, exhibited in the Salon of 1868, was his first major work to introduce a subject with which he would become especially identified, dancers.[25]

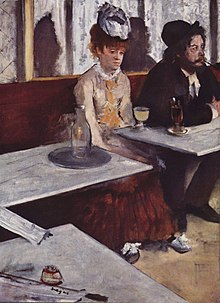

In many subsequent paintings dancers were shown backstage or in rehearsal, emphasizing their status as professionals doing a job. From 1870 Degas increasingly painted ballet subjects, partly because they sold well and provided him with needed income after his brother's debts had left the family bankrupt.[26] Degas began to paint café life as well. He urged other artists to paint "real life" instead of traditional mythological or historical paintings, and the few literary scenes he painted were modern and of highly ambiguous content. For example, Interior (which has also been called The Rape) has presented a conundrum to art historians in search of a literary source; internal evidence suggests that it may be based on a scene from Thérèse Raquin.[27]

As his subject matter changed, so, too, did Degas' technique. The dark palette that bore the influence of Dutch painting gave way to the use of vivid colors and bold brushstrokes. Paintings such as Place de la Concorde read as "snapshots," freezing moments of time to portray them accurately, imparting a sense of movement. The lack of color in the 1874 Ballet Rehearsal on Stage and the 1876 The Ballet Instructor can be said to link with his interest in the new technique of photography. The changes to his palette, brushwork, and sense of composition all evidence the influence that both the Impressionist movement and modern photography, with its spontaneous images and off-kilter angles, had on his work.[23]

Blurring the distinction between portraiture and genre pieces, he painted his bassoonist friend, Désiré Dihau, in The Orchestra of the Opera (1868–69) as one of fourteen musicians in an orchestra pit, viewed as though by a member of the audience. Above the musicians can be seen only the legs and tutus of the dancers onstage, their figures cropped by the edge of the painting. Art historian Charles Stuckey has compared the viewpoint to that of a distracted spectator at a ballet, and says that "it is Degas' fascination with the depiction of movement, including the movement of a spectator's eyes as during a random glance, that is properly speaking 'Impressionist'."[28]

Degas' mature style is distinguished by conspicuously unfinished passages, even in otherwise tightly rendered paintings. He frequently blamed his eye troubles for his inability to finish, an explanation that met with some skepticism from colleagues and collectors who reasoned, as Stuckey explains, that "his pictures could hardly have been executed by anyone with inadequate vision."[29] The artist provided another clue when he described his predilection "to begin a hundred things and not finish one of them,"[30] and was in any case notoriously reluctant to consider a painting complete.

His interest in portraiture led him to study carefully the ways in which a person's social stature or form of employment may be revealed by their physiognomy, posture, dress, and other attributes. In his 1879 Portraits, At the Stock Exchange, he portrayed a group of Jewish businessmen with a hint of anti-Semitism. In 1881 he exhibited two pastels, Criminal Physiognomies, that depicted juvenile gang members recently convicted of murder in the "Abadie Affair". Degas had attended their trial with sketchbook in hand, and his numerous drawings of the defendants reveal his interest in the atavistic features thought by some nineteenth century scientists to be evidence of innate criminality.[31] In his paintings of dancers and laundresses, he reveals their occupations not only by their dress and activities but also by their body type. His ballerinas exhibit an athletic physicality, while his laundresses are heavy and solid.[32]

By the later 1870s Degas had mastered not only the traditional medium of oil on canvas, but pastel as well. The dry medium, which he applied in complex layers and textures, enabled him more easily to reconcile his facility for line with a growing interest in expressive color.

In the mid-1870s he also returned to the medium of etching, which he had neglected for ten years, and began experimenting with less traditional printmaking media—lithographs and experimental monotypes. He was especially fascinated by the effects produced by monotype, and frequently reworked the printed images with pastel.[33]

These changes in media engendered the paintings that Degas would produce in later life. Degas began to draw and paint women drying themselves with towels, combing their hair, and bathing (see: After the Bath). The strokes that model the form are scribbled more freely than before; backgrounds are simplified.

The meticulous naturalism of his youth gave way to an increasing abstraction of form. Except for his characteristically brilliant draftsmanship and obsession with the figure, the pictures created in this late period of his life bear little superficial resemblance to his early paintings. Ironically, it is these paintings, created late in his life, and after the heyday of the Impressionist movement, that most obviously use the coloristic techniques of Impressionism.[34]

For all the stylistic evolution, certain features of Degas's work remained the same throughout his life. He always painted indoors, preferring to work in his studio, either from memory or using models.[35] The figure remained his primary subject; his few landscapes were produced from memory or imagination. It was not unusual for him to repeat a subject many times, varying the composition or treatment. He was a deliberative artist whose works, as Andrew Forge has written, "were prepared, calculated, practiced, developed in stages. They were made up of parts. The adjustment of each part to the whole, their linear arrangement, was the occasion for infinite reflection and experiment."[36] Degas himself explained, "In art, nothing should look like chance, not even movement".[26]

Personality and politics

Degas, who believed that "the artist must live alone, and his private life must remain unknown",[37] lived an outwardly uneventful life. In company he was known for his wit, which could often be cruel. He was characterized as an "old curmudgeon" by the novelist George Moore,[37] and he deliberately cultivated his reputation as a misanthropic bachelor.[17] Profoundly conservative in his political opinions, he opposed all social reforms and found little to admire in such technological advances as the telephone.[37] He fired a model upon learning she was Protestant.[37] Although Degas painted a number of Jewish subjects from 1865 to 1870, his anti-Semitism became apparent by the mid 1870s. His 1879 painting At The Bourse is widely regarded as strongly anti-Semitic, with the facial features of the banker taken directly from the anti-Semitic cartoons rampant in Paris at the time.[38]

The Dreyfus Affair, which divided Paris from the 1890s to the early 1900s, further intensified his anti-Semitism. By the mid 1890s, he had broken off relations with all of his Jewish friends,[16] publicly disavowed his previous friendships with Jewish artists, and refused to use models who he believed might be Jewish. He remained an outspoken anti-Semite and member of the anti-Semitic "Anti-Dreyfusards" until his death.[39]

Reputation

During his life, public reception of Degas' work ranged from admiration to contempt. As a promising artist in the conventional mode, Degas had a number of paintings accepted in the Salon between 1865–1870. These works received praise from Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and the critic, Castagnary.[40] He soon joined forces with the Impressionists, however, and rejected the rigid rules, judgements, and elitism of the Salon—just as the Salon and general public initially rejected the experimentalism of the Impressionists.

Degas's work was controversial, but was generally admired for its draftsmanship. His La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans, or Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, which he displayed at the sixth Impressionist exhibition in 1881, was probably his most controversial piece; some critics decried what they thought its "appalling ugliness" while others saw in it a "blossoming."[41] The suite of nudes Degas exhibited in the eighth Impressionist Exhibition in 1886 produced "the most concentrated body of critical writing on the artist during his lifetime. ... The overall reaction was positive and laudatory."[42]

Recognized as an important artist by the end of his life, Degas is now considered "one of the founders of Impressionism".[43] Though his work crossed many stylistic boundaries, his involvement with the other major figures of Impressionism and their exhibitions, his dynamic paintings and sketches of everyday life and activities, and his bold color experiments, served to finally tie him to the Impressionist movement as one of its greatest early artists.

His paintings, pastels, drawings, and sculpture—most of the latter were not intended for exhibition, and were discovered only after his death—are on prominent display in many museums.

After his death in 1917, more than 150 sculptural works were found in his studio, of which the subjects mainly consisted of race horses and dancers. Degas scholars have agreed that the sculptures were not created as aids to painting. His first and only showing of sculpture during his life took place in 1881 when he exhibited The Little Fourteen Year Old Dancer, only shown again in 1920; the rest of the sculptural works remained private until an exhibition after his death in 1918. Sculpture was not so much in response to his failing eyesight as one more strand to his continuing endeavour to explore different media. Wherever the possibility seemed available, he explored ways of linking graphic art and oil painting, drawing and pastel, sculpture and photography. Degas assigned the same significance to sculpture as to drawing: "Drawing is a way of thinking, modelling another."[26]

Although Degas had no formal pupils, he greatly influenced several important painters, most notably Jean-Louis Forain, Mary Cassatt, and Walter Sickert;[44] his greatest admirer may have been Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.[45]

73 Plaster casts

In 2004, a previously unknown cache of 73 plaster casts created from wax originals sculpted by Edgar Degas was discovered. Art scholars are not in agreement as to what exactly the 73 casts actually are.[46]

After Degas' death, his heirs found in his studio 150 wax sculptures, many in disrepair. They consulted foundry owner Adrien Hébrard, who concluded that 74 of the waxes could be cast in bronze. It is assumed that, except for the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, all Degas bronzes worldwide are cast from surmoulages (i.e., cast from bronze masters). A surmoulage bronze is a bit smaller, and shows less surface detail, than its original bronze mold. The Hébrard Foundry cast the bronzes from 1919–1936, and closed down in 1937, shortly before Hébrard's death.

In 2001, Walter F. Maibaum, an authority on 19th and 20th century European art, was introduced to Leonardo Benatov, owner of the Valsuani Foundry in La Vallée de Chevreuse, France, and possessor of a heretofore unknown plaster cast of the Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. After research and consultation with other experts on Degas, Maibaum was convinced the plaster was an original. In 2004, Mr. Benatov opened a locked stockroom in Valsuani in which 73 additional plasters were stored, all unknown and never listed or catalogued, but consistent with the 73 originals that Degas’ heirs gave to Hébrard Foundry in 1918.

According to Maibaum: “..The moment I gazed upon these remarkable plasters I instantly knew that everything that had been written about Degas’ sculptures in the past had to be reconsidered”. After examining them, Dr. Gregory Hedberg, Director of European Art for Hirschl and Adler Galleries in New York, concluded that the entire group of plasters from the Valsuani Foundry were made during Degas’ lifetime between 1887 and 1912 by the artist’s close friend Albert Bartholomé whom he entrusted with the task.

In 1955, the contents of Bartholomé's widow’s apartment were dispersed and the plasters were brought to Valsuani by the Hébrard caster Palazzolo. It appears, from their condition and provenance, that no bronzes were ever cast from these newly discovered plasters. Plans to cast the newly discovered Degas sculptures, which differ in the rendering of details from the Hébrard casts, have created disagreement among Degas scholars and admirers, some of whom are reserving judgment regarding the authenticity of the plasters.[47]

Gallery

-

The Amateur, 1866, The Metropolitan Museum of Art New York City

-

Horseracing in Longchamps, 1873-1875, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Portrait of Miss Cassatt, Seated, Holding Cards, 1876-1878

-

At the Café-Concert: The Song of the Dog, 1875-1877

-

The Singer with the Glove, 1878, The Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

-

The Millinery Shop, 1885, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

-

Ballet Rehearsal, 1873, The Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts

-

Dancer with a Bouquet of Flowers (Star of the Ballet), 1878

-

Stage Rehearsal, 1878-1879, The Metropolitan Museum of Art New York City

-

Dancers at The Bar, 1888, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

-

Woman in the Bath, 1886, Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Connecticut

-

The Tub, 1886, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

-

The Bath: Woman Supporting her Back, c. 1887, pastel on paper, Honolulu Academy of Arts

-

Kneeling Woman, 1884, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

-

After the Bath, Woman Drying her Nape 1898, Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

-

The Spanish Dance, c. 1885 (bronze cast 1921), bronze, 46.3 x 14.3 cm, Ackland Art Museum

-

Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, cast in 1922 from a mixed-media sculpture modeled ca. 1879–80, Bronze, partly tinted, with cotton skirt and satin hair ribbon, on a wooden base, Metropolitan Museum of Art

See also

References

Notes

- [p] - The name Degas is pronounced as "Deh-Gah".

- ^ a b Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 31

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 11

- ^ Turner 2000, p. 139

- ^ Canaday 1969, p. 930-931

- ^ Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 154

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 43

- ^ Thomson 1988, p. 48

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 23

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p.29

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p.33

- ^ Armstrong 1991, p. 25

- ^ "In the final inventory of his collection, there were twenty paintings and eighty-eight drawings by Ingres, thirteen paintings and almost two hundred drawings by Delacroix. There were hundreds of lithographs by Daumier. His contemporaries were well represented—with the exception of Monet, by whom he had nothing." Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 37

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 26

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 34

- ^ Canaday 1969, p. 929

- ^ a b Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 56

- ^ a b Bade and Degas 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Thomson 1988, p. 211

- ^ Mannering 1994, p. 7

- ^ Hartt 1976, p. 365

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 11

- ^ Armstrong 1991, p. 22

- ^ a b Roskill 1983, p.33

- ^ Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 151

- ^ Dumas 1988, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Growe 1992

- ^ Reff 1976, pp. 200-204

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p.28

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 29

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p.50

- ^ Kendall, et al. 1998, pp. 78–85 (seen at googlebooks here; also see discovermagazine.com

- ^ Muehlig 1979, p. 6

- ^ Thomson 1988, p. 75

- ^ Mannering 1994, pp. 70-77

- ^ Benedek "Style."

- ^ Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Werner 1969, p. 11.

- ^ http://blogs.princeton.edu/wri152-3/f05/eharwood/insider_trading_degas_most_antisemitic_painting.html

- ^ Politics of Vision: Essays on 19th Century Art And Society

- ^ Bowness 1965, pp. 41-42

- ^ Muehlig 1979, p.7

- ^ Thomson 1988, p. 135

- ^ Mannering 1994, p. 6-7

- ^ J. Paul Getty Trust

- ^ Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 48

- ^ The Art Newspaper, Martin Bailey, The silence of the Degas scholars Retrieved April 11, 2010

- ^ Jerusalem Post, Gil Goldfine, The complete sculptures of Edgar Degas Retrieved April 11, 2010

Sources

- Armstrong, Carol (1991). Odd Man Out: Readings of the Work and Reputation of Edgar Degas. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226026957

- Bade, Patrick; Degas, Edgar (1992). Degas. London: Studio Editions. ISBN 1851708456

- Baumann, Felix; Karabelnik, Marianne, et al. (1994). Degas Portraits. London: Merrell Holberton. ISBN 1-85894-014-1

- Benedek, Nelly S. "Chronology of the Artist's Life." Degas. 2004. 21 May 2004.

- Benedek, Nelly S. "Degas's Artistic Style." Degas. 2004. 21 March 2004.

- Bowness, Alan. ed. (1965) "Edgar Degas." The Book of Art Volume 7. New York: Grolier Incorporated :41.

- Brettell, Richard R.; McCullagh, Suzanne Folds (1984). Degas in The Art Institute of Chicago. New York: The Art Institute of Chicago and Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-86559-058-3

- Brown, Marilyn (1994). Degas and the Business of Art: a Cotton Office in New Orleans. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00944-6

- Canaday, John (1969). The Lives of the Painters Volume 3. New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc.

- Dorra, Henri. Art in Perspective New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.:208

- Dumas, Ann (1988). Degas's Mlle. Fiocre in Context. Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum. ISBN 0-87273-116-2

- "Edgar Degas, 1834-1917." The Book of Art Volume III (1976). New York: Grolier Incorporated:4.

- Gordon, Robert; Forge, Andrew (1988). Degas. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1142-6

- Growe, Bernd; Edgar Degas (1992). Edgar Degas, 1834-1917. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. ISBN 3822805602

- Guillaud, Jaqueline; Guillaud, Maurice (editors) (1985). Degas: Form and Space. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-5407-8

- Hartt, Frederick (1976). "Degas" Art Volume 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.: 365.

- "Impressionism." Praeger Encyclopedia of Art Volume 3 (1967). New York: Praeger Publishers: 952.

- J. Paul Getty Trust "Walter Richard Sickert." 2003. 11 May 2004.

- Kendall, Richard; Degas, Edgar; Druick, Douglas W.; Beale, Arthur (1998). Degas and The Little Dancer. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300074972

- Mannering, Douglas (1994). The Life and Works of Degas. Great Britain: Parragon Book Service Limited.

- Muehlig, Linda D. (1979). Degas and the Dance, 5–27 April May 1979. Northampton, Mass.: Smith College Museum of Art.

- Peugeot, Catherine, Sellier, Marie (2001). A Trip to the Orsay Museum. Paris: ADAGP: 39.

- Reff, Theodore (1976). Degas the artist's mind. [New York]: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870991469

- Roskill, Mark W. (1983). "Edgar Degas." Collier's Encyclopedia.

- Thomson, Richard (1988). Degas: The Nudes. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-23509-0

- Tinterow, Gary (1988). Degas. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery of Canada.

- Turner, J. (2000). From Monet to Cézanne: late 19th-century French artists. Grove Art. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22971-2

- Werner, Alfred (1969) Degas Pastels. New York: Watson-Guptill. ISBN 0-8230-1276-X

Further reading

- Capriati, Elio; I Segreti di Degas (2009). Milano: Mjm Editore. ISBN 978-88-95682-68-6

External links

- Edgar Degas at Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Connecticut

- Edgar Degas at Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California

- Edgar Degas - Life and Art

- Degas at the WebMuseum

- PBS on Degas

- Degas, Sickert & Toulouse Lautrec at Tate

- Edgar Degas biography, books & exhibition review by cosmopolis.ch

- Edgar Degas Gallery at MuseumSyndicate

- Degas at Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

- Edgar Degas paintings & interactive timeline

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Edgar Degas. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California.

- [1] The M.T Abraham Center For The Visual Arts

| : Related navpages: |

- 1834 births

- 1917 deaths

- People from Paris

- French painters

- French sculptors

- French printmakers

- French Roman Catholics

- Impressionist painters

- Impressionist sculptors

- Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni

- French military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- Burials at Montmartre Cemetery, Paris

- Alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts