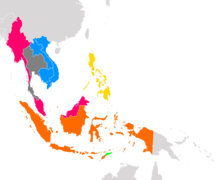

European colonisation of Southeast Asia

Legend:

France

Netherlands

Portugal

Spain

United Kingdom

European colonisation of Southeast Asia began as western influence started to enter the area around the 16th century, when the Dutch and Portuguese were attracted by the lucrative spice trade. The Portuguese arrived in Malacca, Maluku and Timor, and the Spanish established themselves beginning from their conquest of Manila which expand into a larger territory of Spanish East Indies. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries the Dutch arrived in Batavia and established the Dutch East Indies, and the British established themselves in the Strait Settlements and further to British Malaya and Borneo as well in Burma. In the 19th century, the French joined their European counterparts in establishing French Indochina. By the turn of the century, all Southeast Asian nations were colonised except for Thailand.

European colonisation can be split into two distinct phases: the early phase before the Industrial Revolution, and the phase marked by the Industrial Revolution. The primary motivation for the first phase was the accumulation of wealth, but in the second phase, there was a change in the role of the Europeans in Southeast Asia, and capitalistic concerns were no longer the only source of motivation.

Early phase

In the period between the 15th to late 17th centuries, advances in cartography, shipbuilding and navigational skills gave rise to what is now called the Age of Exploration. During this time, the Europeans made many sea voyages around the world in search of new trading routes and opportunities. An early European to visit Southeast Asia was Niccolò de' Conti, who travelled there in the early 15th century.

The early Europeans were drawn to Southeast Asia by the spice trade. There was a great demand for oriental spices at the time in European markers. The spices from Southeast Asia included pepper, cloves, nutmeg, mace and cinnamon. The spice trade was extremely lucrative and the early Europeans were highly motivated to secure a direct trade route in spices between Europe and Asia.

The spice trade was made possible by the maritime trade route. In 1498, the Portuguese navigator, Vasco da Gama, sailed round the Cape of Good Hope and opened up a sea route from Europe to India. Bringing home samples of exotic oriental products, da Gama greatly increased European interest in the new trade route and the new trade route quickly facilitated the expansion of trade. Eventually, the Dutch wrestled control of it from the Portuguese in the 17th century, and in the 18th century, the British gained control of it from the Dutch. Nevertheless, the spice route greatly increased trading activities, deepened the economic relations between Europe and Southeast Asia and as a result, more European merchants found their way to Southeast Asia.

Portugal was the first European power to establish a bridgehead on the lucrative maritime Southeast Asia trade route, with the conquest of the Sultanate of Malacca in 1511. The Netherlands and Spain followed and soon superseded Portugal as the main European powers in the region. In 1599, Spain began to colonise the Philippines. In 1619, acting through the Dutch East India Company, the Dutch took the city of Sunda Kelapa, renamed it Batavia (now Jakarta) as a base for trading and expansion into the other parts of Java and the surrounding territory. In 1641, the Dutch took Malacca from the Portuguese.[note 1] Economic opportunities attracted Overseas Chinese to the region in great numbers. In 1775, the Lanfang Republic, possibly the first republic in the region, was established in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, as a tributary state of the Qing Empire; the republic lasted until 1884, when it fell under Dutch occupation as Qing influence waned.[note 2]

Spread of Christianity

During the 16th century, the Europeans viewed Muslim control of the eastern and southern parts of Europe with concern, as both a religious threat as well as an obstacle to trade. To counter this Muslim threat, the Europeans aimed to spread Christianity across the known world. At the same time, they also searched for profitable trading opportunities. This explained why the Portuguese and Spanish came to Southeast Asia and how they managed to establish their trading ports in strategic locations. By the time the British and the Dutch came to Southeast Asia, trade had become the dominant motive, and religion was less important.

Industrialised phase

The 17th century saw the formation of powerful trading companies such as the British East India Company and its Dutch counterpart VOC (initials for its Dutch name, Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie). This was because the ships needed for the maritime spice trade were too expensive for individual merchants to acquire, and the sea route presented numerous challenges which delayed the recovery of initial financial costs. Sea voyages were dangerous and, before the advent of steam engines, depended on the wind which meant that the journeys were long and unpredictable.

The British East India Company led by Josiah Child, had little interest or impact in the region, and were effectively expelled following the Siam–England war (1687). Britain, in the guise of the British East India Company, turned their attention to the Bay of Bengal following the Peace with France and Spain (1783). During the conflicts, Britain had struggled for naval superiority with the French, and the need of good harbours became evident. Penang Island had been brought to the attention of the Government of India by Francis Light. In 1786 a settlement was formed under the administration of Sir John Macpherson, which formally began British expansion into the Malay States of Southeast Asia.[1][note 3]

In the latter half of the 18th century, however, Europe experienced a massive advancements in science, industry and technology, and this created a tremendous gap in the power relations between the Europeans and people in other parts of the world, including Southeast Asia. This period also saw the initial stages of growing industrialisation that would increase European demand for raw materials. Southeast Asia happened to be rich in the resources needed.

The last quarter of the 19th century was a period when the European economies experienced the full effects of the Industrial Revolution. During this time, there was extensive use of machines to manufacture goods which increased production. This led to a growing accumulation of surplus goods. The manufacturers were thus compelled to find overseas markets to sell their products and increase their profits. One solution was to develop markets in new territories such as Southeast Asia that could use their manufactured goods. This led to the next phase of establishing colonial territories that could be retained as monopoly markets by the Europeans.

However, industrialisation took place against increasing competition among the European powers. This was encouraged by changes in the continental balance of power. The Napoleonic Wars unseated French power. The commercial and naval powers of Britain, which were unrivalled for a time, started to erode later on. Competition among European powers led to the practice of carving up the world into spheres of influence. There was also the need to fill ‘vacuums’ of territories that would otherwise fall under the influence of another competing European power.

The British temporarily possessed Dutch territories during the Napoleonic Wars; and Spanish areas in the Seven Years' War. In 1819, Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a key trading post for Britain in their rivalry with the Dutch. However, their rivalry cooled in 1824 when an Anglo-Dutch treaty demarcated their respective interests in Southeast Asia. British rule in Burma began with the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826).

Early United States entry into what was then called the East Indies (usually in reference to the Malay Archipelago) was low key. In 1795, a secret voyage for pepper set sail from Salem, Massachusetts on an 18-month voyage that returned with a bulk cargo of pepper, the first to be so imported into the country, which sold at the extraordinary profit of seven hundred per cent.[2] In 1831, the merchantman Friendship of Salem returned to report the ship had been plundered, and the first officer and two crewmen murdered in Sumatra. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 obligated the Dutch to ensure the safety of shipping and overland trade in and around Aceh, who accordingly sent the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army on the punitive expedition of 1831. President Andrew Jackson also ordered America's first Sumatran punitive expedition of 1832, which was followed by a punitive expedition in 1838. The Friendship incident thus afforded the Dutch a reason to take over Ache; and Jackson, to dispatch diplomatist Edmund Roberts,[3] who in 1833 secured the Roberts Treaty with Siam. In 1856 negotiations for amendment of this treaty, Townsend Harris stated the position of the United States:

The United States does not hold any possessions in the East, nor does it desire any. The form of government forbids the holding of colonies. The United States therefore cannot be an object of jealousy to any Eastern Power. Peaceful commercial relations, which give as well as receive benefits, is what the President wishes to establish with Siam, and such is the object of my mission.[4]

From the end of the 1850s onwards, while the attention of the United States shifted to maintaining their union, the pace of European colonisation shifted to a significantly higher gear.

This phenomenon, denoted New Imperialism, saw the conquest of nearly all Southeast Asian territories by the colonial powers. The Dutch East India Company and British East India Company were dissolved by their respective governments, who took over the direct administration of the colonies. Only Thailand was spared the experience of foreign rule, though Thailand, too, was greatly affected by the power politics of the Western powers. The Monthon reforms of the late 19th century continuing up till around 1910, imposed a Westernised form of government on the country's partially independent cities called Mueang, such that the country could be said to have successfully colonised itself.[5] Western powers did, however, continue to interfere in both internal and external affairs.[6][7]

By 1913, the British had occupied Burma, Malaya and the northern Borneo territories, the French controlled Indochina, the Dutch ruled the Netherlands East Indies while Portugal managed to hold on to Portuguese Timor. In the Philippines, the 1872 Cavite Mutiny was a precursor to the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898). When the Spanish–American War began in Cuba in 1898, Filipino revolutionaries declared Philippine independence and established the First Philippine Republic the following year. In the Treaty of Paris of 1898 that ended the war with Spain, the United States gained the Philippines and other territories; in refusing to recognise the nascent republic, America effectively reversed her position of 1856. This led directly to the Philippine–American War, in which the First Republic was defeated; wars followed with the Republic of Zamboanga, the Republic of Negros and the Republic of Katagalugan, all of which were also defeated.

The Long Depression also intensified the competition among the European powers. This period of prolonged economic recession saw severe price deflation as well as factors unfavourable to trade. The European governments responded to this crisis by promoting home industries and minimising trade with other European countries. However, as domestic markets and export opportunities quickly became saturated, finding new markets for manufactured goods became more urgent. New colonies overseas, not exposed to the same economic conditions, provided the perfect solution.

During the mid-19th century, the Europeans had certain goals which they regarded as important in the humanitarian sense. One of these goals was expressed in the slogan, ‘The White Man's Burden’ (taken from a line in a poem by Rudyard Kipling), which was the mission to ‘civilise’ (uplift, advance) the ‘less fortunate’ and ‘less gifted’ people of Southeast Asia. Towards this end, they implemented policies providing educational and healthcare services. However, this humanitarian concern was influenced by political concerns, and sometimes arose more out of cultural arrogance than genuine sympathy.

Sometimes, the acquisition of colonies was an attempt to revive declining political and economic status rather than a show of power. France was preoccupied with expanding her colonial empire to recover from her humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. Britain, having lost her dominance in the world economy to newly industrialised countries such as Germany (Prussia united all the German states to form Germany in 1871 after the victory in the Franco-Prussian war) and the United States, saw empire-building as a necessary recourse. It was generally assumed that the establishment of colonies to protect existing trade links would prevent further decline of the European powers.

Role of the Europeans

In the early phase, European control in Southeast Asia was largely confined to the establishment of trading posts. These trading posts were used to store the oriental products obtained from the local traders before they were exported to the European markets. Such trading posts had to be located along major shipping routes and their establishments had to be approved by the local ruler so that peace would prevail for trade to take place. Malacca, Penang, Batavia and Singapore were all early trading posts.

The role of the Europeans changed, however, in the industrialised phase as their control expanded beyond their trading posts. As the trading posts grew due to an increase in the volume of trade, demand for food supplies and timber (to build and repair ships) also increased. To ensure a reliable supply of food and timber, the Europeans were forced to deal with the local communities nearby. These marked the beginnings of territorial control. A good example is the case of Batavia. There, the Dutch extended control over parts of western Java and later to central Java and the east where rice was grown and timber found.

To ensure that trade flourish, the Europeans had to maintain political stability. Sometimes, they interfered with the internal affairs of the natives to maintain peace. The Europeans also tried to impose their culture on their colonies.

Impact

Colonial rule had had a profound effect on Southeast Asia. While the colonial powers profited much from the region's vast resources and large market, colonial rule did develop the region to a varying extent. Commercial agriculture, mining and an export based economy developed rapidly during this period. The introduction Christianity bought by the colonist also have profound effect in the societal change.

Increased labour demand resulted in mass immigration, especially from British India and China, which brought about massive demographic change. The institutions for a modern nation state like a state bureaucracy, courts of law, print media and to a smaller extent, modern education, sowed the seeds of the fledgling nationalist movements in the colonial territories. In the inter-war years, these nationalist movements grew and often clashed with the colonial authorities when they demanded self-determination.

The expansion of European dominance through colonialism was considered extraordinary as it affected the entirety of Southeast Asia significantly. Later on, more common features would emerge, such as the rise of nationalist movements, the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia, and later the Cold War that engulfed many parts of the region. Taken altogether, it can be said that a common core of historical experiences existed, and that this core defined the region, thus justifying the use of the term ‘Southeast Asia’ to describe the region as a single entity.

List of European colonies

- British Burma (1824–1948, merged with India by the British from 1886 to 1937)

- French Indochina (1887–1953, now the countries of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos), including:

- French Laos (1893-1953)

- French Cambodia (1863-1953)

- Annam (now Vietnam) (1883-1953)

- Portuguese Malacca (1511–1641)

- Dutch Malacca (1641–1824)

- British Malaya, included:

- Straits Settlements (1826–1946)

- Singapore – British colony (1819–1959)

- Federated Malay States (1895–1946)

- Unfederated Malay States (1885-1946)

- Federation of Malaya (under British rule, 1948–1963)

- British Borneo (now part of Malaysia), including:

- Labuan (1848–1946)

- North Borneo (1882–1941)

- Crown Colony of North Borneo (1946–1963)

- Crown Colony of Sarawak (1946–1963)

- British Brunei (1888–1984) (British protectorate)

- Spanish Philippines (1565–1898, 2nd longest European occupation in Asia, 333 years),

- British Manila (1762-1764 , Shortly British occupation in Philippines, 2 years)

- Insular Government of the Philippine Islands and Commonwealth of the Philippines, United States colony (1898–1946)

- Portuguese Timor (1702–1975, now East Timor)

- Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) – Dutch colony from 1602–1949 (included Netherlands New Guinea until 1962)

Notes

- ^ For fifty or sixty years, the Portuguese enjoyed the exclusive trade to China and Japan. In 1717, and again in 1732, the Chinese government offered to make Macao the emporium for all foreign trade, and to receive all duties on imports; but, by a strange infatuation, the Portuguese government refused, and its decline is dated from that period. (Roberts, 2007 PDF image 173 p. 166)

- ^ Other experiments in republicanism in adjacent regions were the Japanese Republic of Ezo (1869) and the Republic of Taiwan (1895).

- ^ Company agent John_Crawfurd used the census taken in 1824 for a statistical analysis of the relative economic prowess of the peoples there, giving special attention to the Chinese: The Chinese amount to 8595, and are landowners, field-labourers, mechanics of almost every description, shopkeepers, and general merchants. They are all from the two provinces of Canton and Fo-kien, and three-fourths of them from the latter. About five-sixths of the whole number are unmarried men, in the prime of life : so that, in fact, the Chinese population, in point of effective labour, may be estimated as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and, as will afterwards be shown, to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000! (Crawfurd image 48. p.30)

References

- ^ Crawfurd, John (August 2006) [First published 1830]. "Chapter I — Description of the Settlement.". Journal of an Embassy from the Governor–general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Vol. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. image 52, p. 34. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Trow, Charles Edward. "Introduction". The old shipmasters of Salem. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. xx–xxiii. OCLC 4669778.

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (Digitized 12 October 2007). "Introduction". Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: In the U.S. Sloop-of-War Peacock During the Years 1832–34. Harper & Brothers. OCLC 12212199. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "1b. Harris Treaty of 1856" (exhibition). Royal Gifts from Thailand. National Museum of Natural History. 14 March 2013 [speech delivered 1856]. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

Credits

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Murdoch, John B. (1974). "The 1901–1902 Holy Man's Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.62.1e (digital). Siam Heritage Trust: 38. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ de Mendonha e Cunha, Helder (1971). "The 1820 Land Concession to the Portuguese" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 059.2g (digital). Siam Society. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Oblas, Peter B. (1965). "A Very Small Part of World Affairs" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.53.1e (digital). Siam Society. Retrieved 7 September 2013.