German phosgene attack of 19 December 1915

| First German Phosgene Attack | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Local operations December 1915 – June 1916 Western Front, World War I | |||||||

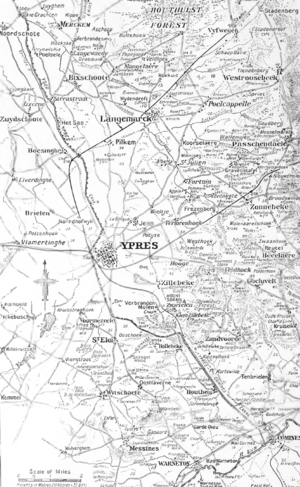

Map of the Ypres district | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Elements of 2 corps specialist Pioneer regiment | 2 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown |

1,069 (gas only) | ||||||

The First German Phosgene Attack took place on 19 December 1915 near Ypres in Belgian Flanders. German gas attacks had begun on 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres using chlorine gas. After an initial surprise, which led to the loss of much of the Ypres salient, the effectiveness of gas as a weapon diminished as both sides produced anti-gas helmets which absorbed chlorine. In December 1915 the German 4th Army conducted an attack at Ypres using a new gas, which was a mixture of chlorine and phosgene, a much more lethal substance. The British took a prisoner who disclosed the intended gas attack and also gleaned information from other sources which led to the divisions of VI Corps being alerted from 15 December.

The gas discharge was accompanied by German raiding patrols, most of which were engaged by small-arms fire while attempting to cross no-man's land. The British anti-gas precautions were successful and prevented a panic or a collapse of the defence, even though British anti-gas helmets had not been treated to repel phosgene. Only the 49th Division had a large number of gas casualties, caused by soldiers in reserve lines not being warned of the gas in time to put on their anti-gas helmets. A careful study by British medical authorities, arrived at a figure of 1,069 gas casualties, of whom 120 men died. After the operation, German opinion concluded that a breakthrough could not be achieved solely by the use of gas.

Background

Gas attacks

During the evening of 22 April 1915, German pioneers released chlorine gas from cylinders placed in trenches at the Ypres salient. The gas drifted into the positions of the French 87th Territorial and the 45th Algerian divisions which occupied the north side of the salient and caused many of the troops to run back from the cloud. A gap had been made in the Allied line, which if exploited by the Germans, could have eliminated the salient and possibly led to the capture of Ypres. The German attack has been intended as a strategic diversion rather than a breakthrough attempt and insufficient forces were available to follow up the success. As soon as German troops tried to advance into areas not affected by the gas, Allied small-arms and artillery fire dominated the area and halted the German advance.[1]

The surprise gained against the French was increased by the lack of protection against gas and because the psychological effect of the unpredictable nature of the substance. Bullets and shells followed a consistent path but gas varied in speed, intensity and extent. A soldier could evade bullets and shells by taking cover but gas followed him, seeped into trenches and dug-outs and had a slow choking effect. A British soldier wrote,

I don't know how long this asphyxiating horror went on. While it lasted it was practically impossible to breathe. Men were going down all about and struggling for air as if they were drowning, at the bottom of our so-called trench. (Lieutenant V. F. S. Hawkins)[2]

The gas was quickly identified as chlorine by an experimental laboratory established at General Headquarters on 27 April by professors Watson, Haldane and Baker. In the first week of May, Watson and Major Cluny McPherson of the Newfoundland Medical Corps sent an anti-gas helmet to the War Office for approval. The helmet was a flannel bag, soaked in glycerine, hyposulphite and sodium bicarbonate and known as a Smoke helmet and by 6 July all of the British troops in France had received one. In November an improved "P" helmet was introduced.[3][4]

In late October 1915, Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) accepted a proposal from the 4th Army for another gas attack east of Ypres and a specialist gas Pioneer regiment was alerted. A mixture of chlorine and phosgene, which was far more lethal, was to be used for the first time.[Note 1] The XXVII Reserve Corps commander General von Schubert objected to the plan since if successful, an attack would move the front line into even more marshy ground just before winter. Schubert preferred to make an attack near Wieltje, with Ypres as the ultimate objective but the resources for such an ambitious attack did not exist. By mid-November, the 4th Army commander [Generaloberst] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg had decided to have the gas cylinders placed along the front of the XXVI Reserve Corps and on the right flank of XXVII Corps.[6]

Prelude

German preparations and plan of attack

Gas cylinders were placed along the front of the XXVI Reserve Corps and on the right flank of the XXVII Reserve Corps. In the XXVI Reserve Corps area, it was found to be impossible to place gas cylinders in a continuous line, due to the irregular nature of the trench lines.[6] A conventional artillery bombardment would be fired but no general attack was to follow. The gas discharge on the front from Boesinghe to Pilckem and Verlorenhoek was to be accompanied by patrols, to observe the effect of the gas and to snatch prisoners and equipment.[7]

British defensive preparations

Anti-gas procedures

Standing orders had been enforced after the gas attacks earlier in 1915. The state of the wind was monitored by an officer in each corps in the area and during conditions favourable for a gas release a "Gas Alert" was issued. A sentry was posted near every alarm horn or gong, at every dug-out big enough for ten men, each group of smaller dug-outs and at all signal offices. Gas helmets and alarms were tested every twelve hours and all soldiers wore the helmet outside the greatcoat or rolled up on their heads, with the top greatcoat button undone to tuck the helmet in. Special lubricants were provided for the working parts of weapons in forward positions.[8]

December 1915

A German Non-commissioned officer of the XXVI Reserve Corps, which held the German line between the Ypres–Roulers and Ypres–Staden railway lines, was captured near Ypres on the night of 4/5 December. The prisoner said that gas cylinders had been dug into the corps front and that a gas attack had recently been postponed. Information had been gleaned from another source that a gas attack was to be made on the Flanders front after 10 December, when the weather was favourable. It had also been discovered that the 26th Reserve Division ?26th? had arrived from the Eastern Front and was at Courtrai. The Allied front line opposite the XXVI Reserve Corps was held by the 6th Division (Major-General C. Ross), the 49th Division (Major-General E. M. Perceval) of VI Corps (Lieutenant-General J. L. Keir) and part of the right flank of the French 87th Territorial Division.[9]

A special warning was issued along with the routine precautions and from 15 December, when the wind was relatively favourable for a gas discharge, the "Gas Alert" was in force. A bombardment by 4.5-inch howitzers of the German line opposite VI Corps was fired, to try to destroy any gas cylinders in the area. The precautionary bombardment was limited by the chronic ammunition shortage, which had led to the twelve howitzers in each division being rationed to 250 shells for the week ending 20 December and 200 for the next week, about three shells per howitzer per day. The bombardment caused damage to the parapets of the German trenches but did not affect the gas cylinders. The firing had not finished when the gas attack began.[10]

Battle

19 December

At 5:00 a.m. an unusual parachute flare was seen to rise from the German lines and at 5:15 a.m. red rockets, which were so unusual that British sentries alerted the officers and men, rose all along the XXVI Reserve Corps front. Soon afterwards, a hissing was heard and a smell noticed. On the left flank in the 49th Division area, which had the 146th and 147th brigades in the line, no man's land was only 20 wide in places and small-arms fire was received from the German trenches before the gas discharge. On the 6th Division front to the right, which had the 18th, 71st and 16th brigades in line, the trenches were about 300 yards (270 m) apart. Slow rifle fire began simultaneously with the discharge and increased after fifteen minutes. Sentries gave the gas warning by sounding the gongs and klaxons, the parapet was manned and rifle and machine-gun fire was opened by some battalions and others waited on events. The divisional artilleries began a shrapnel barrage on their night bombardment lines and no German infantry attack followed, although troops were seen on the parapets of German trenches and many troops were discovered to occupy the German trenches, judged by the volume of rifle-fire directed at a British aircraft which flew low overhead.[11]

Small numbers of German troops were seen to advance from the German line, in one place about twelve men moved forward in single file and at another place about 30 soldiers attacked. A party managed to reach the British parapet before being overwhelmed but the rest were shot down in no man's land. In the 71st Brigade sector north-west of Wieltje a German shrapnel bombardment was taken to mean that no infantry attack was imminent and the defenders went under cover. Lacrymatory and high explosive shells were fired at the right flank of the 49th Division and further back, on roads leading out of Ypres and the British artillery lines but no systematic wire-cutting was observed. Vlamertinghe was bombarded by super-heavy 17-inch howitzers and Elverdinghe by 13-inch howitzers. The British defence scheme was implemented by moving forward the reserves of the 6th and 49th divisions and the 14th Division (Major-General V. A. Couper) in corps reserve, was ordered to stand to.[12]

The German gas discharge on the front from Boesinghe to Pilckem and Verlorenhoek was followed by twenty patrols, which were to observe the effect of the gas and to snatch prisoners and equipment. Only two patrols were able to reach the British line according to German sources and several parties had many losses to British return-fire.[7] The gas formed a white cloud about 50 feet (15 m) high and lasted for thirty minutes before a freshening north-easterly wind blew it away. The effect was felt over a large area because the cloud spread outwards from the 3 miles (4,800 m) width of the attack front to about 8 miles (13 km) wide. The gas cloud moved for about 10 miles (16 km), almost as far as Bailleul. Around 6:15 a.m., green rockets were fired from the German front line and the British lines were bombarded by gas shells, which moved quietly through the air and only exploded with a "dull splash". In the 49th Division area, some troops in support trenches were asleep and were gassed before they could be woken but most were able to don their helmets in time.[13][14]

20–21 December

At 8:00 a.m. on the morning of 20 December, a German observation balloon was sent up and an aeroplane flew low along the front line, followed at 9:00 a.m. by another six German aircraft, which flew as far as Vlamertinghe and Elverdinghe. After the gas shelling, the German artillery returned to high explosive fire until 9:30 a.m. and then diminished the size of the bombardment. At 2:15 a.m. the bombardment increased in intensity and continued periodically until the evening of 21 December.[14]

Aftermath

Analysis

| Month | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| December | 5,675 | ||

| January | 9,974 | ||

| February | 12,182 | ||

| March | 17,814 | ||

| April | 19,886 | ||

| May | 22,418 | ||

| June | 37,121 | ||

| Grand total |

125,141 | ||

The Official Historians of the Reichsarchiv wrote that at zero hour, some of the gas had not been released and gaps appeared in the cloud. Patrols found that the British had not retired from the front line and were engaged with small-arms fire, which caused casualties. Despite the favourable conditions the gas had not had a great effect and it was concluded that a breakthrough could not be obtained just by a gas attack.[16][7] Earlier cloud gas attacks in April and May 1915 had been made against unprotected troops but by December, British troops had been equipped with efficient respirators and anti-gas organization and training had been introduced. The first cotton waste respirators had been replaced by a helmet made of flannelette soaked in an absorbent solution. The "P" helmet, soaked in sodium phenate which absorbed chlorine and phosgene, was in use on 19 December.[17][Note 2]

German gas attacks were made at night or in the early morning, when the wind was favourable and night made it difficult for the defenders to see the gas cloud. Phosgene made the gas cloud more poisonous and the Germans tried to increase the concentration of the gas by discharging it quickly, though this shortened the time of the gas attack. The slow dispersal of cloud gas from depressions and trenches made it difficult for the defenders to measure the duration of the gas discharge. British studies concluded that the Germans tried to surprise the troops with a lethal amount of gas before they could get their helmets on. Soldiers wearing their helmets were safe but one breath of concentrated gas would cause coughing and gasping, which made it very difficult to adjust the helmet. Troops slow in putting their helmets on could be killed by the poison. On 19 December, some troops well behind the front line were affected and helmets were worn at Vlamertinghe, about 8,000 yards (7,300 m) behind the front line.[19] The gas was found to be a mixture of about 80% chlorine and 20% phosgene.[20] The British concluded that the speed of the gas cloud reduced casualties, even though the gas helmets in use had not been treated specifically to resist phosgene.[14]

Casualties

A careful study was made by the British of gas casualties which were calculated at 1,069 of which 120 were fatal, 75% of the casualties being suffered by the 49th Division. Food exposed to the gas was tainted and soldiers who ate it vomited. Some men exposed to the gas, suddenly died about twelve hours later while exerting themselves, despite showing few signs of illness beforehand.[21]

Subsequent operations

The next substantial German gas attack took place from 27–29 April 1916, near the German-held village of Hulluch, a mile north of Loos. The gas cloud and artillery bombardment were followed by raiding parties, which made temporary lodgements in the British lines. Two days later another gas attack was launched, which blew back over the German lines and caused a large number of German casualties, which were increased by British troops firing at German soldiers as they fled in the open. The German gas was a mixture of chlorine and phosgene, which was of sufficient concentration to penetrate the British PH gas helmets. The 16th Division was unjustly blamed for poor gas discipline and it was put out that the gas helmets of the division were of inferior manufacture, to allay doubts as to the effectiveness of the helmet.[22] Production of the Small Box Respirator, which had worked well during the attack, was accelerated.[23]

Notes

- ^ On a lethality index, chlorine was measured at 7,500 and phosgene at 450, in which the smaller number represents the deadlier gas.[5]

- ^ The "PH" helmet, which was impregnated with hexamethylene tetramine along with sodium phenate, was in use soon after and by April 1916 the "Large Box" respirator had been issued to machine-gunners, signallers and some artillerymen.[18]

Footnotes

- ^ Palazzo 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Palazzo 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Palazzo 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 217.

- ^ Palazzo 2000, p. 82.

- ^ a b Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 347.

- ^ a b c Edmonds 1932, p. 162.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, p. 158.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, p. 159.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Magnus 1920, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Edmonds 1932, p. 161.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, p. 243.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 347–348.

- ^ MacPherson et al. 1923, pp. 277–278.

- ^ MacPherson et al. 1923, p. 277.

- ^ MacPherson et al. 1923, p. 278.

- ^ Fries & West 1921, p. 162.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Edmonds 1932, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Fries & West 1921, pp. 198–200.

References

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1927). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (IWM & Battery Press 1995 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-218-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Edmonds, J. E. (1932). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (IWM & Battery Press 1993 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Fries, A. A.; West, C. J. (1921). Chemical Warfare (PDF). New York: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 570125. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - MacPherson, W. G.; Herringham, W. P.; Elliott, T. R.; Balfour, A. (1923). Medical Services: Diseases of the War: Including the Medical Aspects of Aviation and Gas Warfare and Gas Poisoning in Tanks and Mines (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. London: HMSO. OCLC 769752656. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Magnus, L. (1920). The West Riding Territorials in the Great War (N & M Press 2004 ed.). London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. ISBN 1-84574-077-7. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Palazzo, A. (2000). Seeking Victory on the Western Front: The British Army and Chemical Warfare in World War I (Bison Books 2003 ed.). London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8774-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Marden, T. O. (1920). A Short History of the 6th Division August 1914 – March 1919 (BiblioBazaar 2008 ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 1-43753-311-6. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

External links

- Chemical warfare

- Environmental issues with war

- Military equipment of World War I

- War crimes

- World War I crimes

- Conflicts in 1915

- 1915 in France

- Battles of the Western Front (World War I)

- Battles of World War I involving France

- Battles of World War I involving Germany

- Battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom