Flemish people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 7 million (2011 estimate) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 6,450,765[1] | |

| Indeterminable[a] (352,630 Belgians)[2] | |

| 187,750[3] | |

| 13,840–176,615[b][4] | |

| 55,200[3] | |

| 15,130[3] | |

| 6,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Dutch (Flemish Dutch) | |

| Religion | |

| Traditionally: Roman Catholic majority Protestant minorities[a] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Walloons and other Germanic peoples (primarily the Dutch, Afrikaners and Frisians) | |

^a U.S. population census does not differentiate between Belgians and Flemish, therefore the number of the latter is unknown. Flemish people might also indiscriminately identify as Dutch, due to their close association, shared history, language and cultural heritage. There were as many as 4.27 million Dutch Americans, unknown percentage of which might be Flemings. ^b In 2011, 13,840 respondents stated Flemish ethnic origin. Another 176,615 reported Belgian. See List of Canadians by ethnicity | |

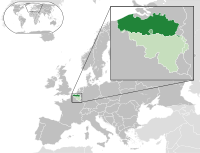

The Flemish or Flemings (Template:Lang-nl; Dutch pronunciation: [vlaːmɪŋɛn] ) are a Germanic ethnic group native to Flanders, in modern Belgium, who speak Dutch, especially any of its dialects spoken in historical Flanders, Brabant and Loon, known collectively as Flemish Dutch.[5] They are one of two principal ethnic groups in Belgium, the other being the French-speaking Walloons. Flemish people make up the majority of the Belgian population (about 60%). Historically, all inhabitants of the medieval County of Flanders were referred to as "Flemings", irrespective of the language spoken.[6] The contemporary region of Flanders comprises a part of this historical county, as well as parts of the medieval duchy of Brabant and the medieval county of Loon.

History

The sense of "Flemish" identity increased significantly after the Belgian Revolution. Prior to this, the term "Flemings" in the Dutch language was in first place used for the inhabitants of the former County of Flanders. Flemish however had been used since the 14th century to refer to the language and dialects of both the peoples of Flanders and the Duchy of Brabant.[7] The modern Belgian province of Limburg was not part of the treaty, and only came to be considered "Flemish" in the 19th century.[citation needed]

In 1830 the southern provinces of the United Netherlands proclaimed their independence. French-dialect speaking population, as well as the administration and elites, feared the loss of their status and autonomy under Dutch rule while the rapid industrialization in the south highlighted economic differences between the two. Under French rule (1794–1815), French was enforced as the only official language in public life, resulting in a Frenchification of the elites and, to a lesser extent, the middle classes. The Dutch King allowed the use of both Dutch and French dialects as administrative languages in the Flemish provinces. He also enacted laws to reestablish Dutch in schools.[8] The language policy was not the only cause of the secession; the Roman Catholic majority viewed the sovereign, the Protestant William I, with suspicion and were heavily stirred by the Roman Catholic Church which suspected William of wanting to enforce Protestantism. Lastly, Belgian liberals were dissatisfied with William for his allegedly despotic behaviour.[citation needed]

Following the revolt, the language reforms of 1823 were the first Dutch laws to be abolished and the subsequent years would see a number of laws restricting the use of the Dutch language.[9] This policy led to the gradual emergence of the Flemish Movement, that was built on earlier anti-French feelings of injustice, as expressed in writings (for example by the late 18th-century writer, Jan Verlooy) which criticized the Southern Francophile elites. The efforts of this movement during the following 150 years, have to no small extent facilitated the creation of the de jure social, political and linguistic equality of Dutch from the end of the 19th century.[citation needed]

After the Hundred Years War many Flemings migrated to the Azores. By 1490 there were 2,000 Flemings living in the Azores. Willem van der Haegen was the original sea captain who brought settlers from Flanders to the Azores. Today many Azoreans trace their genealogy from present day Flanders. Many of their customs and traditions are distinctively Flemish in nature such as Windmills used for grain, São Jorge cheese and several religious events such as the imperios and the feast of the Cult of the Holy Spirit.

Identity and culture

Within Belgium, Flemings form a clearly distinguishable group set apart by their language and customs. However, when compared to the Netherlands most of these cultural and linguistic differences quickly fade, as the Flemish share the same language, similar or identical customs and (though chiefly with the southern part of today's Netherlands) traditional religion with the Dutch.[10] However, the popular perception of being a single polity varies greatly, depending on subject matter, locality and personal background. Generally, Flemings will seldom identify themselves as being Dutch and vice versa, especially on a national level.[11]

This is partly caused by the popular stereotypes in the Netherlands as well as Flanders which are mostly based on the 'cultural extremes' of both Northern and Southern culture.[12] But also in great part because of the history of emancipation of their culture in Belgium, which has left many Flemings with a high degree of national consciousness, which can be very marked among some Dutch-speaking Belgians.[13] Alongside this overarching political and social affiliation, there also exists a strong tendency towards regionalism, in which individuals greatly identify themselves culturally through their native province, city, region or dialect they speak.

Language

Flemings speak Dutch (specifically its southern variant, which is sometimes colloquially called 'Flemish'). It is the majority language in Belgium, being spoken natively by three-fifths of the population. Its various dialects contain a number of lexical and a few grammatical features which distinguish them from the standard language.[14] As in the Netherlands, the pronunciation of Standard Dutch is affected by the native dialect of the speaker. At the same time East Flemish forms a continuum with both Brabantic and West Flemish. Standard Dutch is primarily based on the Hollandic dialect (spoken in the northwestern Netherlands) and to a lesser extent on Brabantic, which is the most dominant Dutch dialect of the Southern Netherlands and Flanders.

Religion

Approximately 75% of the Flemish people are by baptism assumed Roman Catholic, though a still diminishing minority of less than 8% attends Mass on a regular basis and nearly half of the inhabitants of Flanders are agnostic or atheist. A 2006 inquiry in Flanders, showed 55% chose to call themselves religious, 36% believe that God created the universe.[15]

National symbols

The official flag and coat of arms of the Flemish Community represents a black lion with red claws and tongue on a yellow field (or a lion rampant sable armed and langued gules).[16] A flag with a completely black lion had been in wide use before 1991 when the current version was officially adopted by the Flemish Community. That older flag was at times recognized by government sources (alongside the version with red claws and tongue).[17][18] Today, only the flag bearing a lion with red claws and tongue is recognized by Belgian law, while the flag with the all black lion is mostly used by Flemish separatist movements. The Flemish authorities also use two logos of a highly stylized black lion which show the claws and tongue in either red or black.[19] The first documented use[20] of the Flemish lion was on the seal of Philip d'Alsace, count of Flanders of 1162. As of that date the use of the Flemish coat of arms (or a lion rampant sable) remained in use throughout the reigns of the d'Alsace, Flanders (2nd) and Dampierre dynasties of counts. The motto "Vlaanderen de Leeuw" (Flanders the lion) was allegedly present on the arms of Pieter de Coninck at the Battle of the Golden Spurs on July 11, 1302.[21][22][23] After the acquisition of Flanders by the Burgundian dukes the lion was only used in escutcheons. It was only after the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands that the coat of arms (surmounted by a chief bearing the Royal Arms of the Netherlands) once again became the official symbol of the new province East Flanders.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Mainly in the Reformed tradition, although also a scarce population of Lutherans.

- ^ "Structuur van de bevolking – België / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest / Vlaams Gewest / Waals Gewest / De 25 bevolkingsrijke gemeenten (2000–2006)" [Structure of the population - Belgium / Brussels-Capital Region / Flemish Region / Walloon Region / The 25 populated municipalities (2000-2006)] (in Dutch). Belgian Federal Government Service (ministry) of Economy – Directorate-general Statistics Belgium. 2007. Retrieved May 23, 2007.— Note: 59% of the Belgians can be considered Flemish, i.e., Dutch-speaking: Native speakers of Dutch living in Wallonia and of French in Flanders are relatively small minorities which furthermore largely balance one another, hence counting all inhabitants of each unilingual area to the area's language can cause only insignificant inaccuracies (99% can speak the language). Dutch: Flanders' 6.079 million inhabitants and about 15% of Brussels' 1.019 million are 6.23 million or 59.3% of the 10.511 million inhabitants of Belgium (2006); German: 70,400 in the German-speaking Community (which has language facilities for its less than 5% French-speakers), and an estimated 20,000–25,000 speakers of German in the Walloon Region outside the geographical boundaries of their official Community, or 0.9%; French: in the latter area as well as mainly in the rest of Wallonia (3.414 - 0.093 = 3.321 million) and 85% of the Brussels inhabitants (0.866 million) thus 4.187 million or 39.8%; together indeed 100%[dead link]

- ^ Results American Fact Finder (US Census Bureau)

- ^ a b c d "Vlamingen in de Wereld". Vlamingen in de Wereld, a foundation offering services for Flemish expatriates, with cooperation of the Flemish government. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 2011 Canadian Census

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 769. ISBN 0313309841. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ La Flandre Wallonne aux 16e et 17e siшcle suivie... de notes historiques ... - Lebon - Google Livres. Books.google.fr. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ^ Lode Wils. De lange weg van de naties in de Lage Landen, p.46. ISBN 90-5350-144-4

- ^ E.H. Kossmann, De lage landen 1780/1980. Deel 1 1780-1914, 1986, Amsterdam, p. 128

- ^ Jacques Logie, De la régionalisation à l'indépendance, 1830, Duculot, 1980, Paris-Gembloux, p. 21

- ^ National minorities in Europe, W. Braumüller, 2003, page 20.

- ^ Nederlandse en Vlaamse identiteit, Civis Mundi 2006 by S.W Couwenberg. ISBN 90-5573-688-0. Page 62. Quote: "Er valt heel wat te lachen om de wederwaardigheden van Vlamingen in Nederland en Nederlanders in Vlaanderen. Ze relativeren de verschillen en beklemtonen ze tegelijkertijd. Die verschillen zijn er onmiskenbaar: in taal, klank, kleur, stijl, gedrag, in politiek, maatschappelijke organisatie, maar het zijn stuk voor stuk varianten binnen één taal-en cultuurgemeenschap." The opposite opinion is stated by L. Beheydt (2002): "Al bij al lijkt een grondiger analyse van de taalsituatie en de taalattitude in Nederland en Vlaanderen weinig aanwijzingen te bieden voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit. Dat er ook op andere gebieden weinig aanleiding is voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit is al door Geert Hofstede geconstateerd in zijn vermaarde boek Allemaal andersdenkenden (1991)." L. Beheydt, "Delen Vlaanderen en Nederland een culturele identiteit?", in P. Gillaerts, H. van Belle, L. Ravier (eds.), Vlaamse identiteit: mythe én werkelijkheid (Leuven 2002), 22-40, esp. 38. Template:Nl icon

- ^ Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: Accounting for the past, 1650-2000; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ^ Languages in contact and conflict ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. 1995. ISBN 978-1-85359-278-2. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ G. Janssens and A. Marynissen, Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (Leuven/Voorburg 2005), 155 ff.

- ^ Inquiry by 'Vepec', 'Vereniging voor Promotie en Communicatie' (Organisation for Promotion and Communication), published in Knack magazine 22 November 2006 p.14 [The Dutch language term 'gelovig' is in the text translated as 'religious'; more precisely it is a very common word for believing in particular in any kind of God in a monotheistic sense, and/or in some afterlife.

- ^ Template:Nl icon Flemish Authorities - coat of arms De officiële voorstelling van het wapen van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, in zwart - wit en in kleur, werd vastgesteld bij de ministeriële besluiten van 2 januari 1991 (BS 2 maart 1991), en zoals afgebeeld op de bijlagen bij deze besluiten. - flag

- ^ Samples of the black lion without red tongue and claws for the province of East and West Flanders before the regionalization of Belgian provinces:Prof. Dr. J. Verschueren; Dr. W. Pée & Dr. A. Seeldraeyers (1 December 1997). Verschuerens Modern Woordenboek (6th revised ed.). N.V. Brepols, Turnhout. volume M–Z, plate "Wapenschilden" left of p. 1997.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) This dictionary/encyclopaedia was put on the list of school books allowed to be used in the official secondary institutions of education on March 8, 1933 by the Belgian government. - ^ Armorial des provinces et des communes de Belgique, Max Servais: pages 217-219, explaining the 1816 origin of the Flags of the provinces of East and West Flanders and their post 1830 modifications

- ^ Flemish authorities show a logo of a highly stylized black lion either with red claws and tongue (sample: 'error' page by ministry of the Flemish Community) or a completely black version.

- ^ Armorial des provinces et des communes de Belgique, Max Servais

- ^ "Flanders (Belgium)". Flags of the World web site. 2006-12-02. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Velde, François R. (2000-04-01). "War-Cries". Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Olivier, M. (1995-06-13). "Voorstel van decreet houdende instelling van de Orde van de Vlaamse Leeuw (Vlaamse Raad, stuk 36, buitengewone zitting 1995 – Nr. 1)" (PDF) (in Dutch). Flemish Parliament. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)