Flora of Madagascar

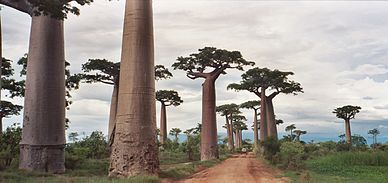

The flora of Madagascar is part of the island's unique wildlife. Madagascar has more than 10,000 plant species, of which more than 90 percent are only found here. The endemics include five unique plant families and such emblematic species as baobab trees or the traveler's palm.

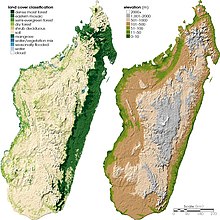

The island has very contrasting vegetation types, with a notable distinction between the west, centre, and east. While the centre is dominated by dry forests and grasslands, the east, receiving most rain from the Indian Ocean, harbours mainly tropical rainforest, and the driest part of the country in the southwest features unique spiny forests.

Human use has changed Madagascar's natural flora dramatically. Rice paddies are a common feature, and other tropical crops such as bananas, yams, cassava, and vanilla are cultivated. Deforestation is a serious problem and has led to the decline of many native vegetation types.

Its high diversity coupled with dramatic decrease of its natural vegetation makes Madagascar one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. A number of areas are protected as nature reserves.

Diversity and endemism

Vascular plants

Madagascar has been described as "one of the most floristically unique places in the world".[1] As of 2016[update], 243 vascular plant families with roughly 11,000 species were known according to the Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Madagascar, of which 83 per cent are only found on the island. This includes five endemic families: Asteropeiaceae, Barbeuiaceae, Physenaceae, Sarcolaenaceae and Sphaerosepalaceae.[2] As many as 96 per cent of Madagascan trees and shrubs were estimated to be endemic.[3]

Ferns and lycophytes have 272 described species in Madagascar. About half of these are endemic; in the scaly tree fern family Cyatheaceae, native to the eastern humid forests, all but three of 47 species are endemic. Six conifers in genus Podocarpus—five endemic—and one cycad, Cycas thouarsii, are native to the island.[2]

In the flowering plants, basal groups and magnoliids account for some 320 Madagascan species, around 94% of which are endemic. The families most rich in species are Annonaceae, Lauraceae, Monimiaceae, and Myristicaceae, containing mainly trees, shrubs, and lianas, and the predominantly herbaceous pepper family (Piperaceae).[2]

Monocots are highly diversified in Madagascar. The most species-rich plant family, orchids (Orchidaceae), fall in this lineage and have over 900 species, of which 85% are endemic. Palms (Arecaceae) have around 200 species in Madagascar (most in the large genus Dypsis), more than three times as many as in continental Africa; all but five are endemic. Other large monocot families include the Pandanaceae with 78 endemic pandan (Pandanus) species, mainly found in humid to wet habitats, and the Asphodelaceae with most species, over 130 endemics, in the succulent genus Aloe. Grasses (Poaceae, 541 species[4]) and sedges (Cyperaceae, 314 species) are diverse, but have lower levels of endemism (40%[4] and 37%, respectively). A national emblem and widely planted, the endemic traveller's tree is the sole Madagascan species in the family Strelitziaceae.[2]

The eudicots account for most of Madagascar's plant diversity. Their most species-rich families on the island are:[2]

- Fabaceae (legumes, 662 species/77% endemic), accounting for many trees in humid and dry forests, including rosewood.

- Rubiaceae (coffee family, 632/92%), with notably over 100 endemic Psychotria and 60 endemic Coffea species.

- Asteraceae (composite family, 533/81%), of which over 100 endemic species in Helichrysum.

- Acanthaceae (acanthus family, 500/94%), with 90 endemic species in Hypoestes.

- Euphorbiaceae (spurge family, 460/94%), notably with the large genera Croton and Euphorbia.

- Malvaceae (mallows, 485/87%), including the large genus Dombeya (177 species, 97% endemic) and seven out of nine baobabs (Adansonia), of which six are endemic.

- Apocynaceae (dogbane family, 363/93%), including the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus).

- Melastomataceae (melastomes, 338/98%), mainly trees and shrubs.

Non-vascular plants and fungi

A checklist from 2012 record 751 moss species and infraspecific taxa, 390 liverworts, and three hornworts for Madagascar. About 34% of the mosses and 19% of the liverworts are endemic. It is unknown how many of those may have gone extinct since their discovery, and a number of species likely remain to be described.[5]

Microscopic organisms such as micro-algae are in general poorly known from Madagascar. A review of freshwater diatoms listed 134 species described, most of them from fossil deposits. It is assumed that Madagascar harbours a rich endemic diatom flora. Diatom deposits from lake sediments have been used to reconstruct paleoclimatic variations on the island.[6]

If fungi are included in the flora, it is assumed that many species remain to be described in Madagascar.[7] A number of edible mushrooms are consumed in the country, especially from the genera Auricularia, Lepiota, the chanterelles (Cantharellus), and the brittlegills (Russula).[7][8] Most of the ectomycorrhizal species are found in plantations of introduced eucalyptus and pine, but also in native tapia woodlands.[7]

The pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, responsible for chytridiomycosis which threatens amphibian populations worldwide, was long considered absent from Madagascar. It was however first recorded in 2010 and confirmed since for various areas and different frog families in the country, alerting scientists about the potential threat to Madagascar's already endangered frog fauna.[9]

Exploration and documentation

Early naturalists

Madagascar and its natural history remained relatively unknown outside the island before the 17th century. Its only overseas connections were occasional Arab, Portuguese, Dutch, and English sailors, who brought home anecdotes and tales about the fabulous nature of Madagascar.[10] With the growing influence of the French in the Indian Ocean, it was mainly French naturalists that documented Madagascar's flora in the following centuries.

Étienne de Flacourt, envoy of France at the military post of Fort Dauphin (Tolagnaro) in the south of Madagascar from 1648 to 1655, wrote the first detailed account of the island, Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar (1658), with a chapter dedicated to the flora. He was the first to mention the endemic pitcher plant Nepenthes madagascariensis and the Madagascar periwinkle.[11][12] About one century later, in 1770, French naturalists and voyagers Philibert Commerson and Pierre Sonnerat visited the country from the Isle de France (now Mauritius).[13] They collected and described a number of plant species, and many of Commerson's specimens were later worked up by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Jean Louis Marie Poiret in France.[14]: 93–95 Sonnerat described, among others, the emblematic traveller's tree, Ravenala madagascariensis.[15] Another contemporary, Louis-Marie Aubert du Petit-Thouars, also visited Madagascar from the Isle de France; he collected on the island for six months and wrote, among others, Histoire des végétaux recueillis dans les îles australes d'Afrique[16] and a work on orchids of Madagascar and the Mascarenes.[14]: 344–345 [17]

Nineteenth century to present

One of the most productive explorers of Malagasy wildlife in the 19th century was Alfred Grandidier. His first visit in 1865 was followed by several other expeditions. He produced an atlas of the island and, in 1885, published his work L'Histoire physique, naturelle et politique de Madagascar, which would comprise 39 volumes.[18] Although his main contributions were in zoology, he was also a prolific plant collector; several plants were named after him, including Grandidier's baobab (Adansonia grandidieri) and the endemic succulent genus Didierea.[14]: 185–187 A contemporary, the British missionary Richard Baron, lived in Madagascar from 1872 to 1907 where he also collected plants and discovered up to 1000 new species;[19] many of his specimens were described by Kew botanist John Gilbert Baker.[20] Baron was the first to catalogue Madagascar's vascular flora in his Compendium des plantes malgaches, including over 4,700 species and varieties known at that time.[19][21]

During the French colonial period, one of the major botanists in Madagascar was Henri Perrier de la Bâthie, who worked in the country from 1896 onwards. He compiled a large herbarium which he later donated to the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Among his publications was notably the first classification of the island's vegetation, La végétation malgache (1921),[22] and Biogéographie des plantes de Madagascar (1936),[23] and he directed the publication of the Catalogue des plantes de Madagascar in 29 volumes.[14]: 338–339 A contemporary and collaborator who equally made large contributions to botany in Madagascar was Henri Humbert, professor in Algiers and later in Paris: He undertook ten expeditions to Madagascar and, in 1936, initiated and edited the monograph series Flore de Madagascar et des Comores.[14]: 214–215 Other important botanists from the colonial era until shortly after Madagascar's independence, describing more than 200 species each, include:[2] Aimée Camus, living in France and specialised on grasses;[2] René Capuron, a major contributor to the woody plant flora; and Jean Bosser, director of the French ORSTOM institute in Antananarivo, working on grasses, sedges, and orchids.[14]: 32–33 Roger Heim was one of the major mycologists working on Madagascar.[24]

Contemporary research

Today, national and international research institutions are documenting the flora of Madagascar. The Botanical and Zoological Garden of Tsimbazaza harbours a botanical garden as well as the country's largest herbarium with over 80,000 specimens.[25] The FO.FI.FA herbarium, with some 60,000 specimens, has primarily woody plants; a number of them and those of the Tsimbazaza herbarium have been digitised and are available online through JSTOR and Tropicos.[25][26] The University of Antananarivo has a research department for Plant Biology and Ecology.[27]

Outside the country, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew are one of the leading institutions in the revision of Madagascar's plant families; Kew also maintains a permanent conservation centre in Madagascar and cooperates with the Silo National des Graines Forestières to build a seed bank of Malagasy Plants in the Millennium Seed Bank project.[28] The National Museum of Natural History in Paris has traditionally been one of the centres for research on the flora of Madagascar. It holds a herbarium with roughly 700,000 Malagasy plant specimens as well as a seedbank and a living collection, and continues to edit the Flore de Madagascar et des Comores series begun by Humbert in 1936.[24] Missouri Botanical Garden maintains the Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Madagascar,[2] a major online resource on the Malagasy flora, and is also present with a dependency in Madagascar.[29]

Vegetation types

Land cover in Madagascar, as of 2007[update][30]

Madagascar features very contrasting and some unique vegetation types, determined mainly by topography, climate, and geology. A mountain range on the east, rising to 2,876 m (9,436 ft) at its highest point, captures most rainfall brought in by trade winds from the Indian Ocean. Consequently, the eastern belt harbours most of the humid forests, while precipitation decreases to the west. The rain shadow region in the southwest has a sub-arid climate. Temperatures are highest on the west coast, with annual means of up to 30 °C (86 °F), while the high massifs have a cool climate, with a 5 °C (41 °F) annual mean locally. Geology features mainly igneous and metamorphic basement rocks, with some lava and quartzite in the central and eastern plateaus, while the western part has belts of sandstone, limestone (including the tsingy formations), and unconsolidated sand.[30]

The marked east–central–west distinction of the Madagascan flora was already described by Richard Baron in 1889.[20] Authors of the 20th century, including Henri Perrier de la Bâthie and Henri Humbert, built up on this and proposed several similar classification systems, based on floristic and structural criteria.[31] A recent classification is the Atlas of the Vegetation of Madagascar (2007), which resulted from the CEPF Madagascar Vegetation Mapping Project[32] and distinguishes 15 vegetation types (including two degraded types) based on satellite imagery and ground surveys; these are defined mainly bases on vegetation structure and can have different species composition in different parts of the island.[30] They partly correspond to the terrestrial ecoregions identified by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in Madagascar.[33]

- Humid forest

This tropical rainforest covers around 8 percent of the island, but used to encompass more than twice as much. It ranges from sea level to 2,750 m (9,020 ft) elevation and is mainly found on the eastern plateaus, on basement rocks with lateritic soils. Annual rainfall is 1,500–2,400 mm (59–94 in), the dry season short or absent. The predominantly evergreen forest, up to 35 m high (115 ft), is composed of diverse tree and understory species from various families such as Burseraceae, Ebenaceae, Fabaceae, and Myristaceae; bamboos and lianas are frequent.[30] The WWF classifies the eastern belt, below 800 m (2,600 ft) elevation, in the Madagascar lowland forests[34] and the montane forests of the central highlands in the Madagascar subhumid forests.[35]

Degraded humid forest—savoka in Malagasy—covers ca. 10 percent of the land. It spans various states of degradation and is composed of forest remnants and planted or otherwise introduced species. It is primarily the result of slash-and-burn cultivation in primary forest. Some forest fragments still harbour a considerable amount of biodiversity.[30]

- Littoral forest

Found in several isolated areas along the eastern coast, this forest type covers less than 1 percent of the land area, on mainly sandy sediments. Climate is humid, with 1,300–3,200 mm (4.3–10.5 ft) annual rainfall. Littoral forest covers sandy soil forest, marsh forest, and grasslands. Its flora includes various tree families, lianas, and epiphytic orchids and ferns; in the marsh forests, pandans (Pandanus) and the traveler's tree (Ravenala madagascariensis) are common.[30] They are part of the WWF's Madagascar lowland forests ecoregion.[34]

- Wooded grassland–bushland mosaic

This diverse mixture of different vegetation types covers roughly 23 percent of the surface. It ranges from sea level to 2,700 m (8,900 ft) elevation and is mainly found on the western and central plateaus and their escarpments, but also in areas of cleared vegetation in the south and east. Substrates are basement rock, sandstone, and lava; climate ranges from sub-humid to sub-arid. The flora has been strongly modified through human-induced fires and grazing, and includes exotic species such as plantations of pine, eucalypt, and cypress. At higher altitudes on thin soil, there is an indigenous, sclerophyllous vegetation that includes Asteraceae, Ericaceae, Lauraceae, and Podocarpaceae shrubs, among others.[30] These forests and thickets on the high massifs are singled out by the WWF as Madagascar ericoid thickets,[36] while most of the remainder falls in the Madagascar subhumid forests ecoregion.[35]

- Plateau grassland–wooded grassland mosaic

This most widespread type covers about 42 percent of the island in the west and the central plateaus, ranging from sea level to 2,700 m (8,900 ft). Geological substrate is variable but mainly igneous and metamorphic in the central highlands. Climate is variable likewise, ranging from sub-humid to sub-arid, with rainfall between 300 and 3,300 mm (0.98 and 10.83 ft) per year. It is supposed to be of human origin in most parts, created and maintained through fire and grazing. Grasses, mainly Loudetia simplex and the endemic Aristida rufescens, are dominating the grassland parts, while wooded parts feature native and introduced trees.[30] Most of this vegetation type falls in the Madagascar subhumid forests ecoregion.[35]

- Tapia forest

This evergreen forest type, dominated by its namesake tapia (Uapaca bojeri), is found on the western and central plateaus, at altitudes of 500–1,800 m (1,600–5,900 ft). It covers less than 1 percent of the surface. The broad regional climate is sub-humid to sub-arid, but tapia forest is mainly found in drier microclimates. Trees other than tapia include Asteropeiaceae, Sarcolaenaceae, and others, with a herbaceous understory. Tapia forest is subject to human pressure, but relatively well adapted to fire.[30] The WWF includes tapia forests in the Madagascar subhumid forests.[35]

- Western humid forest

Confined to a very small plateau region in the south west, on the eastern slope of the Analavelona massif, on lavas and sand, at 700–1,300 m (2,300–4,300 ft) elevation. This isolated humid forest is maintained through condensating moisture from ascending air. The forest is unprotected but the local population considers it sacred.[30] The WWF includes it in the Madagascar subhumid forests.[35]

- Western dry forest

Accounting for roughly 5 percent of the surface, Western dry forest is found in the west, from the northern tip of the island to the Mangoky river in the south. It ranges from sea level to 1,600 m (5,200 ft) in elevation. Climate is sub-humid to dry, with 600–1,500 mm (24–59 in) annual rainfall and a dry season of around six months. Geology is varied and can include limestone forming the eroded tsingy outcrops. Vegetation is diverse; it ranges from forest to bushland and includes trees of the Burseraceae, Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and baobab species.[30] The WWF classifies the northern part of this vegetation as Madagascar dry deciduous forest[37] and the southern part, including the northernmost range of Didiereaceae, as Madagascar succulent woodlands.[38]

- Western sub-humid forest

This forest occurs inland in the south west and covers less than 1 percent surface, mainly on sandstone, at 70–100 m (230–330 ft) elevation. Climate is sub-humid to sub-arid, with 600–1,200 mm (24–47 in) annual rainfall. The vegetation, up to 20 m tall (66 ft) with a closed canopy, includes diverse trees with many endemics such as baobabs (Adansonia), Givotia madagascariensis, or the palm Ravenea madagascariensis. Cutting, clearing and invasive species such as opuntias and agaves threaten this vegetation type.[30] It is part of the WWF's Madagascar subhumid forests.[35]

- South western dry spiny forest-thicket

This vegetation type unique to Madagascar covers ca. 3 percent of its area. It is confined to the sub-arid region in the southwest, at an elevation of up to 300 m (980 ft), on limestone and sandstone bedrocks. Mean annual rainfall is about 540 mm (21 in), and the rain season very short. It is a dense thicket composed of plants adapted to dry conditions, notably through succulent stems or leaves transformed into spines. The characteristic plants are the endemic Didiereaceae family, baobabs, and Euphorbia species.[30] The WWF classifies it as Madagascar spiny thickets.[39]

Degraded spiny forest accounts for ca. 1 percent of the surface and is the result of cutting, clearing, and encroachment. Introduced species associated to disturbed areas, such as agaves and opuntias, are found with remnants of the native flora.[30]

- South western coastal bushland

Located in the same larger southwest region as the spiny forest, this formation is only found along the coast, at an elevation of 0–50 m (160 ft). Climate is sub-arid, with only 370–380 mm (15–15 in) of rainfall per year, concentrated in one month or less. The substrate is mainly unconsolidated sediment. This vegetation type is an open bushland without closed canopy. It is dominated by several tree and shrubs, including Euphorbia species.[30] It is part of the WWF's Madagascar spiny thickets.[39]

- Wetlands

Wetlands cover roughly 1 percent of the island, not counting running water. Marshes, swamp forests and lakes are found in all regions, along with rivers and streams. Typical species of wet habitats are several endemic Cyperus sedges, ferns, pandans (Pandanus), and the traveller's tree (Ravenala madagascariensis). Two species of water lilies, Nymphaea lotus and N. nouchali, are found in the west and east, respectively. Lagoons are mainly found on the east coast, but also occur in the west; they have a specialised halophyte flora. Peat bogs are restricted to highlands above 2,000 m (6,600 ft) elevation; their distinct vegetation includes, among others, Sphagnum moss and sundew species (Drosera). Many wetlands have been converted into rice paddies and are otherwise threatened by destruction and pollution.[30]

- Mangroves

Mangrove forests occur on the western, Mozambique channel coast, from the very north to just south of the Mangoky river delta. Eleven mangrove tree species are known from Madagascar, of which the most frequent belong to the families Acanthaceae, Lecythidaceae, Lythraceae, Combretaceae, and Rhizophoraceae. Mangrove forests are threatened by encroachment and cutting.[30] The WWF lists them as Madagascar mangroves ecoregion.[40]

- Cultivation

Cultivation accounts for at least 3.9 percent of the surface, but its real extent is difficult to estimate. It includes especially rice fields, and there are plantations of sisal as well as pine and eucalyptus. Other important crops are cassava, sweet potatoes, sugar cane, coffee, and vanilla.[30]

Origins and evolution

Nepenthes madagascariensis, endemic to eastern Madagascar, is pictured.

Madagascar's high species richness and endemicity are attributed to its long isolation as a continental island: Once part of the Gondwana supercontinent, Madagascar separated from continental Africa around 150–160, and from the Indian subcontinent 84–91 million years ago (mya).[41] The Madagascan flora was therefore long seen as relict of an old Gondwanan vegetation, separated by vicariance through the continental break-up, although the possibility of some across-ocean dispersal was also admitted.[42] Molecular clock analyses shifted support to immigration via dispersal for most plant and other organismal lineages, given their divergences estimated after Gondwana break-up;[43][44] the only endemic plant lineage on Madagascar sufficiently old to be a possible Gondwana relict appears to be Takhtajania perrieri (Winteraceae).[44] Most plant groups have African affinities, consistent with the relatively small distance to the continent, and strong similarities also exist with the Indian Ocean islands of the Comoros, Mascarenes, and Seychelles. There are however also links to other, more distant floras, such as those of India and Malesia.[44]

After its separation from Africa, still connected with India, Madagascar moved polewards, to a position south of 30° latitude. It moved northwards again and crossed the subtropical ridge between the end of the Cretaceous (66 mya) and the start of the Oligocene (23 mya). This passage likely induced a dry, desert-like climate on the now–separate island, of which the sub-arid spiny forest–thicket in the southwest may be a remnant. Humid forests could only establish once Madagascar was north of the subtropical ridge by the Oligocene. Also, India, still close to the east, moved north towards Eurasia and cleared the eastern seaway in the Middle to Late Eocene, allowing more oceanic precipitation brought in by trade winds. The origin of the Indian Ocean monsoon system after around 8 mya is believed to have further favoured the expansion of humid and sub-humid forests in the Late Miocene.[41]

Several hypotheses exist as to how plants and other organisms have diversified into so many species in Madagascar. They mainly assume either that species diverged in parapatry by gradually adapting to different environmental conditions on the island, for example dry versus humid, or lowland versus montane habitats, or that barriers such as large rivers, mountain ranges, or open land between forest fragments, favoured allopatric speciation.[45]

Human impact

Madagascar was colonised rather recently compared to other landmasses, with first evidence for human presence dating to 2,300[46] or perhaps 4,000 years before present.[47] It is assumed that humans first stayed near the coast and penetrated into the interior only several centuries later. The settlers had a profound impact on the long-isolated environment of Madagascar, although the precise historical timing and scale are not fully understood. The first Europeans arrived in the 16th century, starting an age of overseas exchange. Population growth and transformation of the landscape was particularly rapid since the mid-twentieth century.[46]

Uses of native plants

The native flora of Madagascar is used for a variety of purposes. The English missionary Richard Baron (see also Exploration and documentation: Nineteenth century to present) already described more than one hundred native plants used locally and commercially. These include many timber trees such as native ebony (Diospyros) and rosewood (Dalbergia) species, the raffia palm Raphia farinifera used for fibre, dyeing plants, as well as medicinal and edible plants.[48]

The traveller's tree (Ravenala madagascariensis) has various uses in the east of Madagascar, chiefly as building material.[49] Madagascar's national instrument valiha is made from bamboo and lent its name to the endemic genus Valiha.[50] Yams (Dioscorea) in Madagascar include introduced, widely cultivated species as well as some 30 endemics, all edible.[51] Edible mushrooms, including endemic species, are collected and sold locally (see above, Diversity and endemism: Fungi).

Many native plant species are used as herbal remedies for a variety of afflictions. An ethnobotanical study in the southwestern littoral forest, for instance, found 152 native plants used locally as medicine,[52] and countrywide, over 230 plant species have been used as traditional malaria treatments.[53] The diverse flora of Madagascar holds potential for natural product research and drug production on an industrial scale; the Madagascar periwinkle, source af alkaloids used in the treatment of different cancers, is a famous example.[54]

Agriculture

One of the most characteristic features of agriculture in Madagascar is the widespread cultivation of rice. The cereal is a staple ingredient of Malagasy cuisine and has also been an important crop for export since pre-colonial times.[55] It was likely introduced with early Austronesian settlers,[56] with archaeobotanical evidence existing for the 11th century.[57] Both indica and japonica varieties were introduced early on.[57] Rice was first cultivated in mud flats and marshes near the coast. It reached the highlands much later, and its widespread cultivation in terraced fields was notably promoted with the expansion of the Imerina kingdom in the 19th century.[55] Conversion for rice cultivation has been of the causes for the loss of natural wetlands in Madagascar.[30]

Other major crops, such as greater yam, coconut, taro and turmeric are also believed to have been brought in by early settlers from Asia.[56] Other crops have a likely African origin, such as cowpea, bambara groundnut, oil palm, and tamarind.[56][58] Some crops like teff, sorghum, common millet and plantain may have been present before colonisation, but it is possible that humans brought in new cultivars.[58] Arab traders presumaby brought in fruits such as mango, pomegranate, and grapes. Further crops from farther away were introduced with later European traders and colonists, for example litchi and avocado.[58] Europeans also promoted the cultivation of export crops like cloves, coconut, coffee and vanilla in plantations.[59]: 107 Madagascar remains today the primary vanilla-producing country worldwide.[60]

Forestry in Madagascar involves many exotic species such as eucalypts, pines and acacias.[58] The traditional slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy), practised for centuries, with a growing population today accelerates the loss of primary forests (see below, Threats and conservation).

Introduced plants

More than 1,300 exotic plants have been reported for Madagascar, with the legumes (Fabaceae) as most frequent family. This represents around 10 percent relative to the native flora, a ratio lower than in many islands and closer to what is known for continental floras. Many exotic plant species have been introduced for agriculture or have other uses. Around 600 species have also naturalised and some are considered invasive.[58] A notorious example is the South American water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), which widely spread through subtropical and tropical regions and is considered a serious plant pest in wetlands of Madagascar.[61] In general, invasive plants mostly spread in already disturbed, secondary vegetation, and the remaining primary forests of the east of Madagascar appear little affected.[62]

A prickly pear cactus, Opuntia monacantha, was introduced to southwest Madagascar in the late 18th century by the French colonialists, who used it as natural fence to protect military forts and gardens. The cactus quickly spread and found use as cattle feed by Antandroy pastoralists. In the early 20th century, cochineals were introduced as biological control for the plant that had become a nuisance; they rapidly eradicated most of the cacti. This was probably associated with famine among the Antandroy people, although some authors challenged the causal link between famine and cactus eradication. Today, several Opuntia species are again present mainly in the south of Madagascar, spreading into native vegetation in some areas.[63]

The prickly pears illustrate the dilemma of introduced plants in Madagascar: While many authors see them as a threat to the native flora,[30][62] it has also been argued that they have not yet been directly linked to an extinction of a native species, and that many may actually provide economic or ecological benefits.[58] A number of plants with an origin in Madagascar have become invasive in other regions, such as the traveller's tree in Réunion, or the flamboyant tree (Delonix regia) in various tropical countries.[62]

Threats and conservation

Habitat destruction threatens many of Madagascar's endemic species and has driven others to extinction. In 2003 Ravalomanana announced the Durban Vision, an initiative to more than triple the island's protected natural areas to over 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) or 10 percent of Madagascar's land surface. As of 2011, areas protected by the state included five Strict Nature Reserves (Réserves Naturelles Intégrales), 21 Wildlife Reserves (Réserves Spéciales) and 21 National Parks (Parcs Nationaux).[64] In 2007 six of the national parks were declared a joint World Heritage Site under the name Rainforests of the Atsinanana. These parks are Marojejy, Masoala, Ranomafana, Zahamena, Andohahela and Andringitra.[65] Local timber merchants are harvesting scarce species of rosewood trees from protected rainforests within Marojejy National Park and exporting the wood to China for the production of luxury furniture and musical instruments.[66] To raise public awareness of Madagascar's environmental challenges, the Wildlife Conservation Society opened an exhibit entitled "Madagascar!" in June 2008 at the Bronx Zoo in New York.[67]

The island has been classified by Conservation International as a biodiversity hotspot.[68]

References

- ^ Gautier, L.; Goodman, S.M. (2003). "Introduction to the Flora of Madagascar". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 229–250. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Madagascar". Saint Louis, Antananarivo: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2009–2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Schatz, G.E. (2000). "Endemism in the Malagasy tree flora". In Lourenço, W.R.; Goodman, S.M. (eds.). Diversité et endémisme à Madagascar/Diversity and endemism in Madagascar. Biogéographie de Madagascar. Vol. 2. Bondy: ORSTOM Editions. pp. 1–9. ISBN 2-903700-04-4. (English/French)

- ^ a b Vorontsova, M.S.; Besnard, G.; Forest, F.; Malakasi, P.; Moat, J.; Clayton, W.D.; Ficinski, P.; Savva, G.M.; Nanjarisoa, O.P.; Razanatsoa, J.; Randriatsara, F.O.; Kimeu, J.M.; Luke, W.R.Q.; Kayombo, C.; Linder, H.P. (2016). "Madagascar's grasses and grasslands: anthropogenic or natural?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1823): 20152262. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2262. ISSN 0962-8452.

- ^ Lovanomenjanahary, M.; Andriamiarisoa, R.L.; Bardat, J.; Chuah-Petiot, M.; Hedderson, T.A.J.; Reeb, C.; Strasberg, D.; Wilding, N.; Ah-Peng, C. (2012). "Checklist of the Bryophytes of Madagascar". Cryptogamie, Bryologie. 33 (3): 199–255. doi:10.7872/cryb.v33.iss3.2012.199. ISSN 1290-0796.

- ^ Spaulding, S.A.; Kociolek, J.P. (2003). "Bacillariophyceae, Freshwater Diatoms". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 276–282. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ a b c Buyck, Bart (2008). "The Edible Mushrooms of Madagascar: An Evolving Enigma". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 509–520. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9029-4. ISSN 0013-0001.

- ^ Bourriquet, G. (1970). "Les principaux champignons de Madagascar" (PDF). Terre Malgache (in French). 7: 10–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-02.

- ^ Bletz, M.C.; Rosa, G.M.; Andreone, F.; Courtois, E.A.; Schmeller, D.S.; Rabibisoa, N.H.C.; Rabemananjara, F.C.E.; Raharivololoniaina, L.; Vences, M.; Weldon, C.; Edmonds, D.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Harris, R.N.; Fisher, M.C.; Crottini, A. (2015). "Widespread presence of the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in wild amphibian communities in Madagascar". Scientific Reports. 5: 8633. doi:10.1038/srep08633. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4341422. PMID 25719857.

- ^ Andriamialiasoa, F.; Langrand, O. (2003). "The History of Zoological Exploration of Madagascar". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ Kay, J. (2004). "Etienne de Flacourt, L'Histoire de le Grand [sic] Île de Madagascar (1658)". Curtis's Botanical Magazine. 21 (4): 251–257. doi:10.1111/j.1355-4905.2004.00448.x. ISSN 1355-4905.

- ^ de Flacourt, E. (1661). Histoire de la grande isle Madagascar (2nd ed.). Paris: G. Clousier. (in French)

- ^ Morel, J.-P. (2002). "Philibert Commerson à Madagascar et à Bourbon" (PDF) (in French). Jean-Paul Morel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Dorr, L.J. (1997). Plant Collectors in Madagascar and the Comoro Islands. Richmond, Surrey: Kew Publishing. ISBN 978-1900347181.

- ^ "Tropicos – Ravenala madagascariensis Sonn". Saint Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Du Petit Thouars, A.A. (1806). Histoire des végétaux recueillis dans les îles australes d'Afrique (in French). Paris: Tourneisen fils.

- ^ Du Petit Thouars, A.A. (1822). Histoire particulière des plantes Orchidées recueillies sur les trois îles australes d'Afrique, de France, de Bourbon et de Madagascar (in French). Paris: self-published. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.492.

- ^ Grandidier, A. (1885). Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1599. (in French)

- ^ a b Dorr, L.J. (1987). "Rev. Richard Baron's Compendium des Plantes Malgaches". Taxon. 36 (1): 39–46. doi:10.2307/1221349. ISSN 0040-0262.

- ^ a b Baron, R. (1889). "The Flora of Madagascar". Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Botany. 25 (171): 246–294. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1889.tb00798.x. ISSN 0368-2927.

- ^ Baron, R. (1900–1906). Compendium des Plantes Malgaches. Revue de Madagascar (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Perrier de la Bâthie, H.P. (1921). La végétation malgache (in French). Marseille: Musée colonial.

- ^ Perrier de la Bâthie, H.P. (1936). Biogéographie des plantes de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Société d'éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales.

- ^ a b "Le Muséum à Madagascar" (PDF) (in French). Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Herbier du Parc Botanique et Zoologique de Tsimbazaza, Global Plants on JSTOR". New York: ITHAKA. 2000–2016. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Herbier du FO.FI.FA, Global Plants on JSTOR". New York: ITHAKA. 2000–2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Université d'Antananarivo – Départements & Laboratoires" (in French). Université d'Antananarivo. 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Madagascar – Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew". Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Madagascar". St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Moat, J.; Smith, P. (2007). Atlas of the Vegetation of Madagascar/Atlas de la Végétation de Madagascar. Richmond, Surrey: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. (English/French)

- ^ Lowry II, P.P.; Schatz, G.E.; Phillipson, P.B. (1997). "The classification of natural and anthropogenic vegetation in Madagascar". In Goodman, S.M.; Patterson, B. (eds.). Natural change and human impact in Madagascar. Washington, London: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-683-2.

- ^ "The CEPF Madagascar Vegetation Mapping Project: Project Aims". Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al., eds. (2004). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ a b Crowley, H. (2004). "29 – Madagascar Humid Forests". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Crowley, H. (2004). "30 – Madagascar Subhumid Forests". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 271–273. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ Crowley, H. (2004). "84 – Madagascar Ericoid Thickets". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ Crowley, H. (2004). "33 – Madagascar Dry Deciduous Forests". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 276–278. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ Crowley, H. (2004). "114 – Madagascar Succulent Woodlands". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 417–418. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ a b Crowley, H. (2004). "113 – Madagascar Spiny Thickets". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 415–417. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ Tognetti, S. (2004). "119 – Madagascar Mangroves". In Burgess, N.; D'Amico Hales, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. (eds.). Terrestrial Ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: A Conservation Assessment (PDF). World Wildlife Fund Ecoregion Assessments (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Island Press. pp. 425–426. ISBN 978-1559633642. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-01.

- ^ a b Wells, N.A. (2003). "Some Hypotheses on the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Paleoenvironmental History of Madagascar". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 16–34. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ Leroy, J.F. (1978). "Composition, origin, and affinities of the Madagascan vascular flora". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 65 (2): 535–589. doi:10.2307/2398861. ISSN 0026-6493.

- ^ Yoder, A.; Nowak, M.D. (2006). "Has vicariance or dispersal been the predominant biogeographic force in Madagascar? Only time will tell". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 37: 405–431. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110239. ISSN 1545-2069. JSTOR 30033838.

- ^ a b c Buerki, Sven; Devey, Dion S.; Callmander, Martin W.; Phillipson, Peter B.; Forest, Félix (2013). "Spatio-temporal history of the endemic genera of Madagascar" (PDF). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 171 (2): 304–329. doi:10.1111/boj.12008. ISSN 0024-4074.

- ^ Vences, M.; Wollenberg, K.C.; Vieites, D.R.; Lees, D.C. (2009). "Madagascar as a model region of species diversification" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 24 (8): 456–465. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.011. PMID 19500874. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Burney, D.; Pigott Burney, L.; Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Goodman, S.M.; Wright, H.T.; Jull, A.J.T. (2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 15288523.

- ^ Gommery, D.; Ramanivosoa, B.; Faure, M.; Guérin, C.; Kerloc’h, P.; Sénégas, F.; Randrianantenaina, H. (2011). "Les plus anciennes traces d'activités anthropiques de Madagascar sur des ossements d'hippopotames subfossiles d'Anjohibe (Province de Mahajanga)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 10 (4): 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.01.006. ISSN 1631-0683.

- ^ Anonymous (1890). "Economic Plants of Madagascar". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). 1890 (45): 200–215. doi:10.2307/4118422. ISSN 0366-4457.

- ^ Rakotoarivelo, N.; Razanatsima, A.; Rakotoarivony, F.; et al. (2014). "Ethnobotanical and economic value of Ravenala madagascariensis Sonn. in Eastern Madagascar". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 10 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-10-57. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 4106185. PMID 25027625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Dransfield, S. (2003). "Poaceae, Bambuseae, Bamboos". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 467–471. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ Jeannoda, V.H.; Razanamparany, J.L.; Rajaonah, M.T.; et al. (2007). "Les ignames (Dioscorea spp. de Madagascar : espèces endémiques et formes introduites ; diversité, perception, valeur nutritionelle et systèmes de gestion durable". Revue d'Ecologie (La Terre et La Vie) (in French and with English abstract). 62 (2–3): 191–207. ISSN 2429-6422.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Razafindraibe, M.; Kuhlman, A.R.; Rabarison, H.; et al. (2013). "Medicinal plants used by women from Agnalazaha littoral forest (Southeastern Madagascar)". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 9 (1): 73. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-73. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 3827988. PMID 24188563.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- ^ Rasoanaivo, P.; Petitjean, A.; Ratsimamanga-Urverg, S.; Rakoto-Ratsimamanga, A. (1992). "Medicinal plants used to treat malaria in Madagascar". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 37 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(92)90070-8. ISSN 0378-8741.

- ^ Rasonaivo, P. (1990). "Rain Forests of Madagascar: Sources of Industrial and Medicinal Plants". Ambio. 19 (8): 421–424. ISSN 0044-7447. JSTOR 4313756.

- ^ a b Campbell, G. (1993). "The Structure of Trade in Madagascar, 1750–1810". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 26 (1): 111–148. doi:10.2307/219188. JSTOR 219188.

- ^ a b c Beaujard, P. (2011). "The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants: linguistic and ethnological evidence" (PDF). Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 46 (2): 169–189. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2011.580142. ISSN 0067-270X.

- ^ a b Crowther, A.; Lucas, L.; Helm, R.; et al. (2016). "Ancient crops provide first archaeological signature of the westward Austronesian expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (24): 6635–6640. doi:10.1073/pnas.1522714113. ISSN 0027-8424.

- ^ a b c d e f Kull, C.A.; Tassin, J.; Moreau, S.; et al. (2012). "The introduced flora of Madagascar" (PDF). Biological Invasions. 14 (4): 875–888. doi:10.1007/s10530-011-0124-6. ISSN 1573-1464.

- ^ Campbell, G. (2005). An economic history of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83935-1.

- ^ "FAOSTAT crop data by country, 2014". Food and Agriculture Organization. 2014. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- ^ Binggeli, P. (2003). "Pontederiaceae, Eichhornia crassipes, Water Hyacinth, Jacinthe d'Eau, Tetezanalika, Tsikafokafona". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 476–478. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ a b c Binggeli, P. (2003). "Introduced and invasive plants". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar (PDF). Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 257–268. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ Binggeli, P. (2003). "Cactaceae, Opuntia spp., Prickly Pear, Raiketa, Rakaita, Raketa". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 335–339. ISBN 978-0226303079.

- ^ Madagascar National Parks (2011). "The Conservation". parcs-madagascar.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rainforests of the Atsinanana". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bearak, Barry (24 May 2010). "Shaky Rule in Madagascar Threatens Trees". New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Luna, Kenny. "Madagascar! to Open at Bronx Zoo in Green, Refurbished Lion House". Treehugger. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Conservation International (2007). "Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands". Biodiversity Hotspots. Conservation International. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)