Fortifications of Valletta

| Fortifications of Valletta | |

|---|---|

Is-Swar tal-Belt Valletta | |

| Valletta, Malta | |

Valletta Land Front as seen from Manoel Island | |

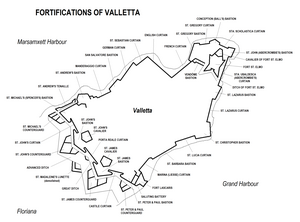

Map of Valletta's fortifications | |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 425: No value was provided for longitude. | |

| Type | City wall |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Malta |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Mostly intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1566–1570s[a] |

| Built by | Order of Saint John British Empire (some modifications) |

| In use | 1571–1970s |

| Materials | Limestone |

| Battles/wars | Capture of Malta (1798) Siege of Malta (1798–1800) World War II |

| Events | Rising of the Priests |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, vi |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Part of | City of Valletta |

| Reference no. | 131 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The fortifications of Valletta (Template:Lang-mt) are a series of defensive walls and other fortifications which surround the capital city of Valletta, Malta. The first fortification to be built was Fort Saint Elmo in 1552, but the fortifications of the city proper began to be built in 1566 when it was founded by Grand Master Jean de Valette. Modifications were made throughout the following centuries, with the last major addition being Fort Lascaris which was completed in 1856. Most of the fortifications remain largely intact today.

The city of Valletta, along with Nicosia in Cyprus, was considered to be a practical example of an ideal city of the Renaissance, and this was due to its fortifications as well as the urban life within the city.[1] The fortifications were well known throughout Europe by the 17th century, and might have influenced the designs of part of the Fortress of Luxembourg.[2] In an 1878 book, Valletta was described as "one of the best fortified [cities] in the world."[3] Today, Valletta's fortifications are regarded as the most important of the fortifications of Malta,[4] and they form part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[5]

History

Background

The construction of a fortified city on the Sciberras Peninsula was first proposed in 1524, when the Order of St. John sent a commission to inspect the Maltese Islands.[6] Back then, the only fortification on the peninsula was a militia watchtower built by the Aragonese in 1488.[7] The tower was strengthened in 1533, but the proposed city was not built since the Order focused on building the fortifications of Birgu, which had become their base.[8]

In 1551, an Ottoman force briefly attacked Malta, and then sacked Gozo and captured Tripoli, and as a result, the Order set up a commission to improve the island's fortifications. In 1552, the Aragonese watchtower was demolished and Fort Saint Elmo was built in its place. The fort played a significant role in the Great Siege of Malta of 1565. It eventually fell after a month of fierce fighting (in which the Ottoman general Dragut was killed). The knights held out in Birgu and Senglea until a relief force arrived, and the siege was lifted.[9]

Construction

After the Order emerged victorious from the siege, it received financial support from Europe, which was used to construct the new capital city on the Sciberras Peninsula. The Italian engineer Francesco Laparelli was sent by the Pope to design the city's fortifications,[10] which were designed along the Italian bastioned system.[11] Laparelli's original design consisted of a bastioned enceinte, with nine cavaliers and a ditch. The city was to be designed along a grid plan, and was to include a naval arsenal and a Manderaggio (a harbour for small ships).[6]

The city's first stone was laid by Grand Master Jean de Valette on 28 March 1566, and the new city was called Valletta in his honour. The city walls were among the first structures to be built within the city, and were largely complete by the 1570s. Some changes were made to the design while the city was being constructed, and only two cavaliers were constructed, while the arsenal and Manderaggio were never built. Fort St. Elmo, which had been severely damaged in the 1565 siege, was also rebuilt and integrated in the city walls.[6]

The city of Valletta officially became the capital city of Malta and the seat of the Order on 18 March 1571, although it was still unfinished.[12] By the end of the 16th century, Valletta was the largest settlement in Malta.[11]

Improvements and modifications

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Valletta's fortifications were strengthened with the construction of various outworks, consisting of four counterguards along the land front, as well as a covertway and a glacis. The northern end of the peninsula, including Fort St. Elmo, was also enclosed in a bastioned enceinte (known as the Carafa Enceinte) in the late 1680s to prevent a landing from the sea.[7]

Despite the modifications, it was realized that the walls of Valletta were not strong enough to withstand a long siege. In 1635, construction of the Floriana Lines commenced, enclosing Valletta's land front. The Floriana Lines were also modified until the 18th century. Later on, the suburb of Floriana developed in the area between the Floriana Lines and the Valletta Land Front, and it is now a town in its own right.[6]

The flanks of the city were further protected in the 17th and 18th century, with the construction of the Santa Margherita Lines, Cottonera Lines and Fort Ricasoli on the Grand Harbour side, and Fort Manoel and Fort Tigné on the Marsamxett side.[13] Further proposals, including construction of fortifications on Corradino and Ta' Xbiex, were also made but were never implemented.[14]

French occupation and British rule

The fortifications of Valletta first saw use during the French invasion of Malta on 9 June 1798. The Order capitulated only three days later on 12 June, and Valletta and its fortifications were handed over to the French. Upon viewing the fortifications, Napoleon reportedly remarked "I am very glad that they opened the gate for us."[15]

A couple of months after the beginning of the French occupation, the Maltese people rebelled against the French and blockaded them in the Harbour area with British, Neapolitan and Portuguese support. The French managed to hold out in Valletta until September 1800, when General Vaubois capitulated to the British, who took control of the islands.[16]

Various modifications were made to Valletta's fortifications during British rule. The most significant of these was the construction of Fort Lascaris between 1854 and 1856. Other alterations included the addition of batteries and concrete gun emplacements, changes to parapets and their embrasures, and the construction of gunpowder magazines. All three original Hospitaller gateways to Valletta were demolished, and two of them were replaced by larger gates.[17]

The British proposed the demolition of the fortifications a number of times in the 19th century. The first proposal was made by Major-General Henry Pigot at the beginning of the century.[18] In 1853, a proposal was made to demolish Saint James Cavalier to make way for a military hospital. In 1855, Sir John Lysaght Pennefather proposed the construction of a citadel on the high ground of the Sciberras peninsula, on the site of the Valletta Land Front and the surrounding area.[19] In 1872, the demolition of the city's outworks was proposed, while the demolition of the entire land front was suggested in 1882.[6] Eventually, the fortifications were left largely intact, and the only part that was demolished was St. Madeleine's Lunette, which was located near the entrance to the city (on the site now occupied by the Triton Fountain).[20]

The fortifications were eventually decommissioned between the late 19th or early 20th centuries. Some parts, such as Fort St. Elmo, Fort Lascaris and the Saluting Battery, remained in use until after World War II, with Fort St. Elmo being decommissioned in 1972.[21] The fortifications were included on the Antiquities List of 1925.[22]

In the 1960s, the 19th century Porta Reale was demolished to make way for a modern City Gate.[23]

Present day

The first plans to restore the fortifications of Valletta, along with those of Birgu, Mdina and the Cittadella, were made in 2006.[24][25] Restoration started in 2010, with the project being described as "the biggest in a century". Squatters were evicted from public lands around the fortifications.[26] The upper part of Fort Saint Elmo has been restored, while its lower parts have been cleaned up.[27] The Chapel of St. Roche on St. Michael's Counterguard, which was bombed in World War II, was rebuilt in 2014 as part of the restoration.[28]

In 2011, the City Gate which had been built in the 1960s was demolished, and a new City Gate was completed in 2014.[29]

Layout

Land front

The Valletta Land Front is the large bastioned enceinte enclosing the landward approach to the city. It consists of the following:[30]

- St. Michael's Bastion, also known as Spencer's Bastion[31] – a demi-bastion on the western extremity of the land front. Two windmills were built on it in 1674, but they were demolished in the 19th century.[32][33] The bastion now forms part of Hastings Gardens.[34]

- St. John's Curtain – the curtain wall linking St. Michael's and St. John's Bastions. It now forms part of Hastings Gardens.[35]

- St. John's Bastion – a large obtuse-angled bastion with a reconstructed echaugette at its salient angle. It now forms part of Hastings Gardens.[36]

- St. John's Cavalier – a pentagonal cavalier overlooking St. John's Bastion. It is now the embassy of the SMOM to Malta.[37]

- Porta Reale Curtain, also known as St. James Curtain – the curtain wall linking St. John's and St. James Bastions. The city's main gate is located within the curtain wall.[38] The gate was rebuilt five times, with the present one being constructed between 2011 and 2014 to a design by Renzo Piano.

- St. James Bastion – a large obtuse-angled bastion with an echaugette at its salient angle. Its thick parapets with embrasures have been dismantled. The bastion is occupied by the Central Bank of Malta and a car park.[39]

- St. James Cavalier – a pentagonal cavalier overlooking St. James Bastion. It is now a cultural centre.[40]

- Castile Curtain – the curtain wall linking St. James and St. Peter & Paul Bastions. Its parapet has been largely dismantled to make way for the road leading from Floriana to Valletta.[41]

- St. Peter and St. Paul Bastion – a two-tiered corner bastion on the eastern extremity of the land front. The upper part is now the Upper Barrakka Gardens, while the lower part contains the Saluting Battery.[42] The 19th-century Fort Lascaris is located below the bastion.

The entire land front is surrounded by a deep ditch.[43] Remains of a flanking battery within the ditch were unearthed in 2012.[44]

The bastions are further protected by the following outworks:

- St. Michael's Counterguard – a three-tiered counterguard built in 1640 near St. Michael's Bastion. Its lower tier contains an echaugette at its salient angle, and a small chapel dedicated to St. Roche.[45] The chapel was destroyed in World War II, but was rebuilt in 2014.[28]

- St. John's Counterguard – a pentagonal counterguard built in 1640 near St. John's Bastion. Its salient angle contains an echaugette, and it also contains a gunpowder magazine. It is currently used as a football ground.[46]

- St. Madeleine's Lunette – a lunette that protected Porta Reale Curtain and the entrance to the city. It was dismantled in the 19th century, and its site is now occupied by the Triton Fountain.[20]

- St. James Counterguard – a pentagonal counterguard built in 1640 near St. James Bastion. Its salient angle contains an echaugette, and it also contains a gunpowder magazine. Its central platform houses the Central Bank of Malta annex.[47]

- St. Peter and St. Paul Counterguard – a two-tiered counterguard built in 1640 near St. Peter and St. Paul Bastion. Its salient angle contains an echaugette, and it also contains a gunpowder magazine and a concrete observation platform.[48]

The outworks were surrounded by an advanced ditch, but only a part of it remains since most of it was filled in with rubble.[20]

Marsamxett enceinte

The enceinte along the side facing Marsamxett Harbour starts from St. Michael's Bastion of the Valletta Land Front, and ends at St. Gregory's Bastion of Fort St. Elmo. It consists of the following:[30]

- St. Andrew Tenaille – a small tenaille beneath St. Michael's Bastion.[49]

- St. Andrew's Bastion – an asymmetrical pentagonal bastion. It is two-tiered, with its lower part originally containing the Marsamxett Gate, which was demolished in the early 20th century.[50] A small faussebraye is located beneath the bastion. Ponsonby's Column was built on the bastion in 1838, but it was destroyed by lightning in 1864.[51]

- Manderaggio Curtain – the curtain wall linking St. Andrew's and San Salvatore Bastions. It was originally divided into two parts, to allow ships to enter the Manderaggio, but the breach was walled up when work on the Manderaggio was abandoned.[52]

- San Salvatore Bastion – a flat-faced artillery platform. Various World War II air raid shelters were dug within the bastion.[53]

- German Curtain – a small curtain wall north of San Salvatore Bastion. Air raid shelters were also dug within its walls. It is sometimes referred to as a bastion.[54]

- St. Sebastian Curtain – a small curtain wall north of the Germain Curtain. Air raid shelters were also dug within its walls. It is sometimes referred to as a bastion.[55]

- English Curtain – a long curtain wall near St. Elmo Bay, overlooked by Auberge de Bavière. It contains the Jews' Sally Port and a number of air raid shelters. A reconstructed echaugette is located between the English and French Curtains.[56]

- French Curtain – a long curtain wall near St. Elmo Bay, linked to Fort Saint Elmo.[57]

Grand Harbour enceinte

The enceinte along the side facing the Grand Harbour starts from St. Peter and St. Paul Bastion of the Valletta Land Front, and ends at St. Ubaldesca Curtain of Fort St. Elmo. It consists of the following:[30]

- Fort Lascaris, also known as Lascaris Battery or Lascaris Bastion – a casemated battery near St. Peter & St. Paul Bastion, built by the British between 1854 and 1856. The Lascaris War Rooms are located nearby.[58]

- Marina Curtain, also known as Liesse Curtain – curtain wall linking St. Peter & St. Paul and St. Barbara Bastions. It originally contained Del Monte Gate, which was demolished and replaced by Victoria Gate in the 19th century.[59]

- St. Barbara Bastion – a flat-faced bastion with a low parapet. An echaugette is located at the bastion's south corner.[60]

- St. Lucia Curtain – curtain wall linking St. Barbara and St. Christopher Bastions.[61]

- St. Christopher Bastion – a two-tiered pentagonal bastion, today breached to make way for the Valletta ring road.[62] The upper part contains the Lower Barrakka Gardens, while the lower part contains the Siege Bell War Memorial and the Monument to the Unknown Soldier. A low battery was built near the bastion in the 1680s, but most of it was dismantled to make way for the ring road.[63]

- St. Lazarus Curtain – curtain wall linking St. Christopher and St. Lazarus Bastions.[64]

- St. Lazarus Bastion – a flat-faced bastion containing several British gun emplacements and a magazine.[65]

Fort Saint Elmo

Fort Saint Elmo is the oldest part of the city walls, and it commands the entrance to both the Grand Harbour and Marsamxett. The fort and the surrounding area consists of the following:[30]

- Upper St. Elmo – the original star fort, consisting of two demi-bastions, two flanks and two faces, a parade ground, barracks and a large cavalier.

- Vendôme Bastion – a bastion built in 1614 linking the French Curtain to Fort St. Elmo, containing an echaugette. After being surrounded by the Carafa Enceinte, it was converted into a magazine, and later an armoury. The bastion is now part of the National War Museum.[66]

- Carafa Enceinte – the bastioned enceinte built around the fort after 1687. It consists of the following bastions:

- St. Gregory Bastion – an asymmetrical bastion with a long left face. It was altered by the British to house QF 6 pounder 10 cwt guns.[67]

- St. Gregory Curtain – a curtain wall linking St. Gregory and Conception Bastions. It contains various British gun emplacements.[68]

- Conception Bastion, also known as Ball's Bastion – a small pentagonal bastion, containing a number of gun emplacements, magazines, and gun crew accommodation. Sir Alexander Ball was buried in the salient of the bastion.[69]

- Sta. Scholastica Curtain – curtain wall linking Conception and St. John Bastions. It contains a gun emplacement for a RML 12.5 inch 38 ton gun, as well as other British modifications.[70]

- St. John Bastion, also known as Abercrombie's Bastion – a large asymmetrical bastion at St. Elmo Point, the tip of the Sciberras Peninsula. The bastion contains several British gun emplacements and magazines.[71]

- St. Ubaldesca Curtain, also known as Abercrombie's Curtain – a long curtain wall linking St. John and St. Lazarus Bastions. It contains a number of British gun emplacements.[72]

Some barrack blocks are located in the area between Upper St. Elmo and the Carafa Enceinte.

References

- ^ Cosmescu, Dragos. "Nicosia". fortified-places.com. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Luxembourg". fortified-places.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- ^ Pembroke Fetridge, William (1874). The American Travellers' Guides: Hand-books for Travellers in Europe and the East, Being a Guide Through Great Britain and Ireland, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Greece, Switzerland, Tyrol, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Russia, Spain, and Portugal. Fetridge & Company. p. 517.

- ^ "Malta restores her historic fortifications". Arx - International Journal of Military Architecture and Fortification. 8: 7. July 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "City of Valletta". UNESCO World Heritage List. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Attard, Sonia. "The Valletta Fortifications". aboutmalta.com. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Fort St. Elmo" (PDF). Heritage Malta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2013.

- ^ Zammit, Vincent (1992). Il-Gran Mastri - Ġabra ta' Tagħrif dwar l-Istorja ta' Malta fi Żmienhom - L-Ewwel Volum 1530-1680 (in Maltese). Valletta: Valletta Publishing & Promotion Co. Ltd. p. 22.

- ^ Jackson, James (7 July 2007). "History's bloodiest siege used human heads as cannonballs". Daily Mail. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Eccardt, Thomas M. (2005). Secrets of the Seven Smallest States of Europe: Andorra, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City. New York City: Hippocrene Books. p. 235. ISBN 9780781810326.

- ^ a b "Valletta - 1566". MilitaryArchitecture.com. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Gaul, Simon (2007). Malta, Gozo & Comino. New Holland Publishers. p. 100. ISBN 9781860113659.

- ^ "Knights' Fortifications around the Harbours of Malta". UNESCO Tentative Lists. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Spiteri, Stephen C. (2014). "Fort Manoel". ARX Occasional Papers. 4. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Valletta - The Fortifications". romeartlover.tripod.com. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "The Conflict for Malta, 1798 – 1802". napoleon-series.org. December 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (18 November 2012). "Let's hide the majestic bastions". Times of Malta. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Regimental Hospitals and Military Hospitals of the Malta Garrison". maltarmc.com. British Army Medical Services And the Malta Garrison 1799 – 1979. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Advanced Ditch - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Gusman, George R. (5 April 2012). "Fort St Elmo". Times of Malta. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Protection of Antiquities Regulations 21st November, 1932 Government Notice 402 of 1932, as Amended by Government Notices 127 of 1935 and 338 of 1939". Malta Environment and Planning Authority. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ^ Attard, Chris (24 August 2008). "The gate triumphant". Times of Malta. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Zammit, Ninu (12 December 2006). "Restoration of forts and fortifications". Times of Malta. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ "A fortune on fortifications". Times of Malta. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ Ameen, Juan (1 February 2010). "Restoration starts on Valletta bastions". Times of Malta. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ "Updated - Upper Fort St Elmo restoration nears completion". Times of Malta. 4 November 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Counterguard Chapel Reconstructed". MilitaryArchitecture.com. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ Calleja, Claudia (6 May 2011). "City Gate bites the dust". Times of Malta. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d Meli, Pavla Antonia (1998). An Introduction to the Hospitaller Military Architecture of Valletta.

- ^ Simpson, Donald H. (1958). "Some public monuments of Valletta 1800–1955" (PDF). Melita Historica. 2 (3): 157.

- ^ "Windmill St Michael's Bastion 1". The Malta Windmill Database. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Windmill St Michael's Bastion 2". The Malta Windmill Database. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Michael Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St John Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St John Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St John Cavalier - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Porta Reale Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St James Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St James Cavalier - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Castile Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "SS Peter and Paul Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Main Ditch - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Flanking battery discovered in Valletta Ditch". MilitaryArchitecture.com. 25 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Michael Counterguard - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St John Counterguard - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St James Counterguard - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "SS Peter and Paul Counterguard - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Andrew Tenaille - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Andrew Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "The lost landmarks of Malta: Ponsonby's Column, Valletta". The Malta Independent. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Manderaggio Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "San Salvatore Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "German Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Sebastian Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "English Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "French Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Lascaris Battery - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Marina Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Barbara Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Lucy Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Christopher Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Grunenburg low battery - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Lazarus Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Lazarus Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Vendôme Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Gregory Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St Gregory Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Conception Bastion - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Sta Scholastica Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "St John Bastion Caraffa - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ "Sta Ubaldesca Curtain - Valletta" (PDF). National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

Notes

- ^ Most of the city walls were built between 1566 and the 1570s. The earliest part, Fort Saint Elmo, had been built in 1552 on the site of a tower built in 1488. Modifications and additions continued throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, with the last major addition being Fort Lascaris in 1856.