François Caron

François Caron | |

|---|---|

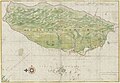

A map of Japan in François Caron's "A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam". | |

| 1st Director-General of the French East India Company | |

| In office 1667–1673 | |

| 8th Governor of Formosa | |

| In office 1644–1646 | |

| Preceded by | Maximiliaan le Maire |

| Succeeded by | Pieter Anthoniszoon Overtwater |

| 12th Opperhoofd in Japan | |

| In office 2 February 1639 – 13 February 1641 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolaes Couckebacker |

| Succeeded by | Maximiliaan le Maire |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1600 Brussels |

| Died | 5 April 1673 (aged 72–73) at sea, near Portugal |

| Nationality | Dutch, French |

| Spouse | Constantia Boudaen |

François Caron (French pronunciation: [fʁɑ̃swa kaʁɔ̃]; 1600 – 5 April 1673) was a French Huguenot refugee to the Netherlands who served the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) for 30 years, rising from cook's mate to the director-general at Batavia (Jakarta), only one grade below governor-general.[1] He retired from the VOC in 1651, and was later recruited to become director-general of the newly formed French East Indies Company in 1665 until his death in 1673.[2]

Caron is sometimes considered the first Frenchman to set foot in Japan,[3] although he was actually born in Brussels to a family of Huguenot refugees.[4] He only became a naturalized citizen of France when he was persuaded by Colbert to become head of the French East Indies Company, in his 60s.[5] Thus the native-born French Dominican missionary Guillaume Courtet may have the stronger claim. Regardless, the first known instance of any Franco-Japanese relations precedes them both, being the visit of Hasekura Tsunenaga to France in 1615.

Japan

[edit]

Caron began as a cook's mate[6] on board the Dutch ship Schiedam bound for Japan, where he arrived at Hirado in 1619. He transferred off the ship (either legitimately or via desertion) and began working in Hirado, becoming a full factory assistant in 1626. He quickly developed an aptitude for the Japanese language, and became involved with a local woman (the daughter of Eguchi Jūzaemon) with whom he had six children.[6] In 1627 he served as interpreter on a VOC mission to the shogunal capital of Edo, the first of many diplomatic trips he would make.[6]

On 9 April 1633, Caron was promoted to senior merchant, making him the second ranking Company official in Japan. In 1636, the new VOC Director-General Philip Lucasz, wishing to learn about the territories he was charged with overseeing, sent a list of 31 questions about Japan which Caron was charged with answering. Caron's answers formed the outline for his work Beschrijvinghe van het machtigh coninckrijcke Jappan ("Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan"), published as an appendix to a corporate history in 1645 and as an independent book in 1661. This was one of the first reports to introduce Japan in any detail to a European audience and was widely read, receiving translations into German, French, and English.[7]

Caron was a gifted diplomat and was important to Dutch efforts to ingratiate themselves with the Shogunate at whose mercy their trade operated. In 1636, on another mission to Edo, Caron presented a magnificent copper lantern (which was installed and still stands at Nikkō Tōshō-gū shrine) as a gift to secure the release of the hostage Pieter Nuyts, who as VOC ambassador to Japan had instigated a diplomatic incident so severe it forced the shutdown of Hirado for several years.[7][8]

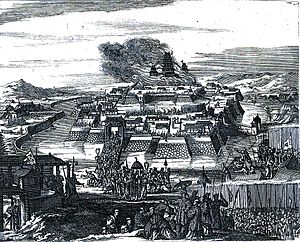

On 3 February 1639, Caron succeeded Nicolaes Couckebacker as the VOC opperhoofd (chief factor or merchant) in Japan. At this time, the shogunate was implementing severe isolationist policies, including the expulsion of nearly all foreigners and the criminalization of Christian proselytizing. The Portuguese trading out of Nagasaki were completely expelled, and the VOC warehouses at Hirado were destroyed, ostensibly because one was engraved with the Christian date of its erection ("AD 1638"). The Dutch, now the only Europeans allowed to trade on Japanese soil, were forced to relocate to the small artificial island of Dejima, although Caron ended his term as opperhoofd shortly before the move took place in the summer of 1641.[9]

Return to the Netherlands

[edit]

In 1641, Caron's Japan contract with the company expired, and he went to Batavia awaiting a transfer to Europe, accompanied by his family.[10] At that time, he was nominated member of the Council of the East Indies, the governing body of the VOC in Asia, next to the governor-general. On 13 December 1641 Caron sailed back to Europe as commander of the merchant fleet.

New assignments in Asia

[edit]Although he was rewarded handsomely for his services with a capital of 1,500 guilders, he again left for Asia in 1643 aboard the Olifant. He arrived in Batavia to find that his Japanese consort had died. As they were never legally married, Caron submitted a formal petition to legitimize his children by her, which was accepted. Meanwhile, during his brief return to Europe, he had become engaged to Constantia Boudaen, who arrived in 1645 and bore him a further seven children.[10]

In September 1643, he headed an army of 1,700 men against the Portuguese in Ceylon. In 1644, Caron was then named governor of Formosa (Taiwan); and was the chief VOC official on the island until 1646.[11] During this period, Caron's achievements included restructuring the production of rice, sulfur, sugar and indigo, and moderating the trade with Chinese pirates.

He had to return to Batavia in 1646. In 1647, he was appointed director-general, second in command after the governor-general. In 1651, Caron was recalled to the Netherlands, together with Cornelis van der Lijn, due to allegations of private trade, but he successfully defended his case, and was able to resign with honor from the company.

Appointment with the French East Indies Company

[edit]The arenas of French rivalry with England and Holland expanded to Asia in 1664 when the French Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert persuaded Louis XIV to grant a patent to a newly contrived French East Indies Company. Somehow Colbert managed to entice Caron into accepting a leadership role in this nascent enterprise. He became the company's Director General in 1665.[12] This action was perceived as treason by the Dutch, and Caron was banned eternally from the Provinces.

Japan and China

[edit]Caron advocated for establishing trade with both Japan and China, laying out a system of purchasing silks and other trade good from China, then selling them in Japan for silver at "60 or 70 percent profit". This silver could then be immediately used to purchase more goods from China to sell in a "wheel of commerce," self-sustaining after only an initial outlay of silver from France itself. In Caron's view, "this is the only trade that can enrich the French Company".[13] An official letter from Louis XIV to the Emperor of Japan was drawn up and instructions prepared for its delivery and subsequent trade negotiations, but it seems that this plan was not carried to fruition and the letter was never conveyed to Japan.[14] It is unlikely that this effort would have succeeded, as Japan was deeply committed to its Sakoku policy of isolation at that time.

Madagascar

[edit]In 1665, François Caron sailed to Madagascar. The Company failed to found a colony on Madagascar but established ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon (now Réunion) and Isle de France (now Mauritius). In the late 17th century, the French established trading posts along the east coast.

India

[edit]Caron succeeded in founding French outposts at Surat (1668) and at Masulipatam (1669) in India;[15] and Louis XIV acknowledged those successes by awarding him the Order of St. Michael.[2] He was "Commissaire" at Surat between 1668 and 1672. The French East India Company formally set up a trading centre at Pondicherry in 1673. This outpost eventually became the chief French settlement in India.

In 1672, he helped lead French forces in Ceylon, where the strategic bay at Trincomalee was captured and St. Thomé (also known as Meilâpûr) on the Coromandel coast was also taken;[15] however, the consequences of his military success was short-lived. The French were driven out these modest conquests while Caron was en route to Europe in 1673.[2]

He died as his ship sank off Lisbon on 5 April 1673, while he was returning to Europe.

Honors

[edit]- Order of St. Michael, 1672

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Asia Society. (1874). Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Frazer, Robert Watson. (1896). British India, p. 42.

- ^ References [1]:

- "Si on peut dire de lui qu'il était français, il est probablement le seul français qui ait visité le Japon sous l'ancien régime." Diderot ; le XVIIIe siecle en europe et au Japon, Colloque franco-japonais ... - Page 222 by Hisayasu Nakagawa - 1988

- "En 1635 ce fut le tour de François Caron, sur lequel nous voudrions nous arrêter un moment, ... comme le premier Français venu au Japon et à Edo." Histoire de Tokyo - Page 67 by Noël Nouët - Tokyo (Japan) - 1961 - 261 pages

- "A titre de premier représentant de notre langue au Japon, cet homme méritait ici une petite place" (Bulletin de la Maison franco-japonaise by Maison franco-japonaise (Tokyo, Japan) - Japan - 1927 Page 127) - ^ "Colbert avait alors sous la main François Caron, qui, né en Hollande de parents français, avait été embarqué pour le Japon dès l'âge le plus tendre". Societe de la Revue des Mondes, François Buloz, Page 140 [2]

"Francois Caron was born in 1600 of Huguenot parents, who were then settled in Brussels, but who shortly after his birth moved to the United Provinces." A True Description of the Mighty Kingdoms of Japan and Siam (1986)[3] - ^ Yavari, Neguin et al. (2004). Views From The Edge: Essays In Honor Of Richard W. Bulliet, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Otterspeer, Willem. (2003). Leiden Oriental Connections, 1850–1940, p. 355.

- ^ a b Maes, Ben (2014). "François Caron and his Beschryvinghe van Iappan – His Perception of the Japanese". MaRBLe Research Papers. 6: 117–132. doi:10.26481/marble.2014.v6.221.

- ^ Mochizuki, Mia M. (2009), "Deciphering The Dutch In Deshima", Boundaries and their Meanings in the History of the Netherlands, Brill, pp. 63–94, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176379.i-258.23, ISBN 9789047429814

- ^ Summary of Francois Caron's diary Archived 4 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Historiographical Institute at the University of Tokyo. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b Leup, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543–1900). p. 8, pp. 62-63

- ^ Campbell, William. (1903). Formosa Under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records, p. 75.

- ^ Ames, Glenn J. (1996). Colbert, Mercantilism, and the French Quest for Asian Trade. Northern Illinois University Press. p. 30.

- ^ Chardin, John (1927) [1st pub. 1720]. Travels In Persia. London: Argonaut Press. p. 19.

- ^ Hildreth, Richard (1905). Japan As It Was and Is (2nd ed.). Boston: Phillip, Sampson and Company. p. 204.

- ^ a b Pope, George Uglow. (1880). A Text-book of Indian History, p. 266.

Further reading

[edit]- Ames, Glenn J. (1996). Colbert, Mercantilism, and the French Quest for Asian Trade. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-207-9.

- Campbell, William. (1903). Formosa Under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd.

- Danvers, Frederick Charles. (1888). Report to the Secretary of State for India in Council on the Records of the Records of the India Office: Records Relating to Agencies, Factories and Settlements not Now Under the Administration of the Government of India. London: Printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO), by Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Frazer, Robert Watson. (1896). British India. London: G.P. Putnam & Sons.

- Leup, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543-1900). London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5

- Otterspeer, Willem. (1989). Leiden Oriental Connections, 1850-1940. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-09022-4 (paper)

- Pope, George Uglow. (1880). A Text-book of Indian History. London: W. H. Allen.

- Proust, Jacques (2003). "Un déscendant de huguenots français au japon au debut XVIIe siècle" (PDF). Académie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier.

- Jozef Rogala. (2001). A Collector's Guide to Books on Japan in English: A Select List of Over 2500 Titles with Subject Index. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-873410-91-2 (paper)

- Yavari, Neguin, Lawrence G. Potter and Jean-Marc Ran Oppenheim (2004). Views From The Edge: Essays In Honor Of Richard W. Bulliet. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13472-9 (cloth)

- Mémoires de François Martin, Fondateur de Pondichéry (1665-1694), publiées par Alfred Martineau, Bibliothèque d'Histoire Coloniale, Paris, 1934