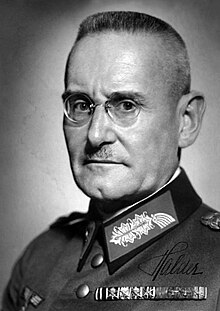

Franz Halder

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

Franz Halder | |

|---|---|

Franz Halder | |

| Born | 30 June 1884 Würzburg, Germany |

| Died | 2 April 1972 (aged 87) Aschau im Chiemgau, Bavaria |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1902–1945 |

| Rank | Generaloberst |

| Battles / wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes |

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German General and the chief of the OKH General Staff from 1938 until September 1942, when he was dismissed after frequent disagreements with Adolf Hitler. His diary during his time as chief of OKH General Staff has been a very good source for authors that have written about such subjects as Adolf Hitler, the Second World War and the NSDAP (The Nazi party). In William Shirer's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Halder's diary is cited hundreds of times.

Early life

Halder was born in Würzburg, the son of General Max Halder. In 1902, he joined the 3rd Royal Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment in Munich. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1904, upon graduation from War School in Munich, then he attended Artillery School (1906–07) and the Bavarian Staff College (War Academy) (1911–1914), both in Munich.

In 1914, Halder became an Ordnance Officer, serving in the Headquarters of the Bavarian 3rd Army Corps. In August, 1915 he was promoted to Hauptmann (Captain) on the General Staff of the 6th Army (at that time commanded by Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria). During 1917 he served as a General Staff officer in the Headquarters of the 2nd Army, before being transferred to the 4th Army.

Interwar era

Between 1919 and 1920 Halder served with the Reichswehr War Ministry Training Branch. Between 1921 and 1923 he was a Tactics Instructor with the Wehrkreis VII in Munich.

In March 1924 Halder was promoted to major and by 1926 he served as the Director of Operations (Oberquartiermeister of Operations: O.Qu.I.) on the General Staff of the Wehrkreis VII in Munich. In February 1929 he was promoted to Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel), and from October 1929 through late 1931 he served on the Training staff in the Reichswehr Ministry.

After being promoted to Oberst (colonel) in December 1931, Halder served as the Chief of Staff, Wehrkreis Kdo VI, in Münster (Westphalia) through early 1934. During the 1930s the German military staff thought that Poland might attack the detached German province of East Prussia. As such, they reviewed plans as to how to defend East Prussia.

After being promoted to Generalmajor, equal to a U.S./British Brigadier general, in October 1934, Halder served as the Commander of the 7th Infantry Division in Munich.

Recognized as a fine staff officer and planner, in August 1936 Halder was promoted to Generalleutnant (rank of a division commander, hence equivalent to a US Army Major General). He then became the director of the Manoeuvres Staff. Shortly thereafter, he became director of the Training Branch (Oberquartiermeister of Training, O.Qu.II), on the General Staff of the Army, in Berlin between October 1937 and February 1938. During this period he directed important training maneuvers, the largest held since the reintroduction of conscription in 1935.

On 1 February 1938 Halder was promoted to General der Artillerie (rank of a corps commander, equivalent to a US Army three-star General). Around this date General Wilhelm Keitel was attempting to reorganize the entire upper leadership of the German Army. Keitel had asked Halder to become Chief of the General Staff (Oberquartiermeister of operations, training & supply; O.Qu.I ) and report to General Walther von Reichenau. However, Halder declined as he felt he could not work with Reichenau very well, due to a personality dispute. As Keitel recognized Halder's superior military planning skills, Keitel met with Hitler and enticed him to appoint General Walther von Brauchitsch as commander-in-chief of the German Army. Halder then accepted becoming Chief of the General Staff of the Army (Oberkommando des Heeres) on 1 September 1938, and succeeded General Ludwig Beck.

A week later, Halder presented plans to Hitler on how to invade Czechoslovakia with a pincer movement by General Gerd von Rundstedt and General Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb. Instead, Hitler directed that Reichenau should make the main thrust into Prague. Neither invasion plan was necessary once Mussolini persuaded Hitler and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain back to the bargaining table in Munich. In the run up to the war, Halder — in an attempt to avoid what they were certain would be a catastrophic war for Germany — was the main actor in a plot with several other generals in the Wehrmacht and Abwehr to remove Hitler from power. A plot was put in place, ready to go at Halder's command, which would be given if Hitler gave the order to proceed with the planned invasion. The plot included a plan to kill Hitler and say "he died trying to escape" (they all agreed he would be too dangerous to keep alive).[1] However, on 29 September Chamberlain capitulated to Hitler’s demands, and the British and French surrendered the largely German populated Czech region of Sudetenland to Germany, with Hitler promising to stop there. (Which promise Hitler broke the following spring.) Halder put an immediate stop to the coup attempt, only hours away from reality, as peace had been preserved – for the moment. Chamberlain's appeasement at Munich meant the end of the plot, which shook Halder took the core and left him weeping according to Halder's former adjutant, Burkhard Mueler-Hildebrand.[2] There would be no war with France and England over the Sudetenland. Hitler's popularity reached an all-time high. A coup then was not possible, nor desirable. The catastrophe Halder and the other generals feared was averted. On 1 October German troops entered the Sudetenland.

World War II

Halder participated in the strategic planning for all operations in the first part of the war. For his role in the planning and preparing of the invasion of Poland he received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 27 October 1939.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, the generally accepted start of World War II. On 19 September, Halder noted in his diary that he had received information from then SS-Gruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich that the SS (Einsatzgruppen) was beginning its campaign to "clean house" in Poland of Jews, intelligentsia, Catholic Clergy, and the aristocracy. This led to future criticism by historians that Halder knew about the killings of Jews much earlier than he later acknowledged during post-World War II interviews, and that he failed to object to such killings. Halder noted in his diary his doubts "about the measures intended by Himmler".[3]

During November 1939, Halder conspired with General Brauchitsch. Halder declared that he would support Brauchitsch if he were to try to curtail Hitler’s plans for further expansion of the war, but Brauchitsch declined (the so-called Zossen Conspiracy). Brauchitsch and Halder had decided to overthrow Hitler after the latter had fixed "X-day" for the invasion of France for 12 November 1939, an invasion that both officers believed to be doomed to failure.[4] During a meeting with Hitler on 5 November, Brauchitsch had attempted to talk Hitler into putting off "X-day" by saying that morale in the German Army was worse than what it was in 1918. This statement enraged Hitler, who then harshly berated Brauchitsch for incompetence.[5] After that meeting, both Halder and Brauchitsch told Carl Friedrich Goerdeler that overthrowing Hitler was simply something that they could not do, and that he should find other officers if that was what he really wanted to do.[6] Equally important, following heavy snowstorms, on 7 November 1939 Hitler put off "X-Day" until further notice, removing the reason that had most motivated Brauchitsch and Halder to consider overthrowing Hitler.[7] On 23 November 1939, Goerdeler met with Halder to ask him to reconsider his attitude.[8] Halder gave Goerdeler the following reasons why he wanted nothing to do with any plot to overthrow Hitler:

- That the men who staged the November Revolution and signed the armistice that took Germany out of a losing war were hated all over the Reich as the "November Criminals".[8] General Erich Ludendorff had launched the Kaiserschlacht in March 1918, which led directly to Germany's defeat in November 1918. This should have hurt Ludendorff's reputation, yet most people in Germany still considered Ludendorff one of Germany's greatest heroes.[8] So even if Hitler were to launch an invasion of France that signally failed, most people would still support him, and unless Hitler was discredited, which seemed unlikely, anyone who acted against him to end the war would be considered a "new November Criminal".[8] Therefore the Army could do nothing.

- That Hitler was a great leader, and there was nobody to replace him.[8]

- That most of the younger officers in the Army were extreme National Socialists who would not join a putsch.[9]

- That Hitler deserved "a last chance to deliver the German people from the slavery of English capitalism".[8]

- Finally, that "one does not rebel when face to face with the enemy".[10]

Despite all of Goerdeler's best efforts, Halder would not change his mind.[10]

While Halder opposed Hitler’s expanded war plans, like all officers he had taken a personal loyalty oath to Hitler. Thus, he felt unable to take direct action against the Führer. At one point, Halder thought the situation to be so desperate that he considered shooting Hitler himself.[11] A colonel close to Halder noted in his diary that "Amid tears, Halder had said for weeks that he had a pistol in his pocket every time he went to Emil [cover name for Hitler] in order to possibly gun him down."[11]

At the end of 1939, Halder oversaw development of the invasion plans of France, the Low Countries, and the Balkans. In late 1939-early 1940, Halder was an opponent of Operation Weserübung, which he believed was doomed to failure, and made certain that the OKH had nothing to do with the planning for Weserübung, which was entirely the work of OKW and the OKM.[12] Halder initially doubted that Germany could successfully invade France. General Erich von Manstein's bold plan for invading France through the Ardennes Forest proved successful, and ultimately led to the fall of France. In early April 1940, Halder had a secret meeting with Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, who asked him to consider a putsch while the Phoney War was still on, hoping that the British and French were still open to a negotiated peace.[13] Halder refused Goerdeler's request.[14] Goerdeler told Halder that too many people had already died in the war, and his refusal to remove Hitler at this point would ensure that the blood of millions would be on his hands.[14] Halder told Goerdeler that his oath to Hitler and his belief in Germany`s inevitable victory in the war precluded his acting against the Nazi regime.[14] Halder told Goerdeler that "The military situation of Germany, particularly on account of the pact of non-aggression with Russia is such that a breach of my oath to the Führer could not possibly be justified", that only if Germany was faced with total defeat would he consider breaking his oath, and that Goerdeler was a fool to believe that World War II could be ended with a compromise peace.[14]

On 19 July 1940, Halder was promoted to Generaloberst. In August, he began working on Operation Barbarossa, the invasion plan for the Soviet Union. Shortly thereafter, to curtail Halder’s military-command power, Hitler limited his involvement in the war by restricting him to developing battle plans for only the Eastern Front[citation needed]. On 17 March 1941, in a secret meeting with Halder and the rest of the most senior generals, Hitler stated that Germany was to disregard all of the rules of war in the East, and the war against the Soviet Union was to be a war of extermination.[15] Halder, who was so vocal in arguing with Hitler about military matters, made no protest.[16] On 30 March 1941, in another secret speech to his leading generals, Hitler described the sort of war he wanted Operation Barbarossa to be (according to the notes taken by Halder), a:

"Struggle between two ideologies. Scathing evaluation of Bolshevism, equals antisocial criminality. Communism immense future danger...This a fight to the finish. If we do not accept this, we shall beat the enemy, but in thirty years we shall again confront the Communist foe. We don't make war to preserve the enemy...Struggle against Russia: Extermination of Bolshevik Commissars and of the Communist intelligentsia...Commissars and GPU personnel are criminals and must be treated as such. The struggle will differ from that in the west. In the east harshness now means mildness for the future."[17]

Though General Halder's notes did not record any mention of Jews, the German historian Andreas Hillgruber argued that, because of Hitler's frequent statements at the same time about the coming war of annihilation against "Judeo-Bolshevism", his generals could not have misunderstood that Hitler's call for the total destruction of the Soviet Union also comprised a call for the total destruction of the Jewish population of the Soviet Union.[17]

In 1941, contrary to his post-war claims, Halder did not oppose the Commissar Order. Rather, he welcomed it, writing that: "Troops must participate in the ideological battle in the Eastern campaign to the end".[18] As part of the planning for Barbarossa, Halder declared in a directive that, in the event of guerrilla attacks, German troops were to impose "collective measures of force" by massacring entire villages.[19] Halder's order was in direct contravention of international agreements banning collective reprisals. In December 1941, Hitler fired von Brauchitsch and assumed the command of OKH himself. Halder was not happy about this, but chose to stay on as the best way of ensuring that Germany won the war.[14] Halder appeared on the 29 June 1942 cover of Time magazine.

During the summer of 1942, Halder told Hitler that he was underestimating the number of Soviet military units. Hitler argued that the Red Army was nearly broken. However, Halder had recently read a book about Stalin's defeat of Anton Denikin between the Don bend and what was then Tsaritsyn during the Russian Civil War. That battle resulted in Tsaritsyn being renamed Stalingrad. Halder was convinced the German Sixth Army was in the same position that Denikin was back then. Furthermore, Hitler did not like Halder’s objections to sending General Manstein’s 11th Army (then finishing the siege of Sevastopol, at the other end of the front) to assist in the attack against Leningrad. Halder also thought that an attack into the Caucasus was ill-advised. Finally, because of Halder’s disagreement with Hitler’s conduct of the war, Hitler concluded that the general no longer possessed an aggressive war mentality. The final straw came after Halder learned of an intelligence report showing Stalin could muster as many as 1.5 million men north of Stalingrad and west of the Volga. He told Hitler that the situation along the Don was a disaster waiting to happen if Stalin turned that force loose on Stalingrad. In response, Hitler gave a speech announcing that he intended to find a replacement for Halder. Halder walked out stating "I am leaving", and was retired into the "Fuhrer Reserve" on 24 September 1942.

On 23 July 1944, following the failed July 20 assassination attempt on Hitler's life by German Army officers, Halder was arrested by the Gestapo. Although he was not involved in the July 20 plot, intense interrogations of the conspirators revealed that Halder had been involved in earlier conspiracies against Hitler. Halder was imprisoned at both the Flossenbürg and Dachau concentration camps. Halder's wife Gertrud chose to, and was allowed to, accompany her husband into imprisonment. On 31 January 1945, Halder was officially dismissed from the army. His service to Germany during Hitler's reign was plagued by complexity and personal misgivings but his professed role in possible intrigue during his tenure as the Chief of Staff make his survival for a remarkable story, especially when one considers the plight of others who fell into disfavor or mistrust with Hitler. As one historian remarked when comparing his fate to that of many of his comrades among the General Staff, Halder was indeed "fortunate."[20] In the last days of April 1945, together with some members of the families of those involved with the July 20 plot and other 'special' prisoners, he was transferred to the South Tyrol, where the entire group of nearly 140 prisoners was liberated from their SS guards by members of the Wehrmacht, and then turned over to US troops on May 4 after the SS guards fled.[21] Halder spent the next two years in an Allied prisoner of war camp.

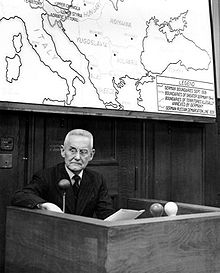

After World War II

During the 1950s, Halder worked as a war historian advisor to the U.S. Army Historical Division, for which he was awarded the Meritorious Civilian Service Award in 1961. During the early 1950s Halder advised on the redevelopment of the post-World War II German army (see: Searle's "Wehrmacht Generals"). He died in 1972 in Aschau im Chiemgau, Bavaria.

Awards

- 1914 Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class

- 1939 Clasps to the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (27 October 1939)

- Prussian Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, Knight's Cross with Swords

- Bavarian Military Merit Order, 4th Class with Crown and Swords

- Saxon Albert Order, Knight 1st Class with Swords

- Austro-Hungarian Military Merit Cross, 3rd Class with War Decoration

- Cross of Honor (Ehrenkreuz für Frontkämpfer)

- U.S. Meritorious Civilian Service Award (1961)[22]

Publications

Halder wrote Hitler als Feldherr in German (1949) which was translated into English as Hitler as War Lord (1950); and The Halder Diaries (1976). The latter diaries were used, before being published, by American historian William Shirer, as a major primary source for his monumental work The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, along with other confidential documents and manuscripts.

In reviewing Halder's personality, the British author Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote: "Halder is a military snob, believing that no amateur can ever understand the mysteries of war." Author Kenneth Macksey wrote: "Quick, shrewd and witty, he was a brilliant specialist in operational and training matters and the son of a distinguished general. He supported Beck's resistance to Hitler, but when it came to a crunch was no real help. Flirt as he did, in September, with those opposed to Hitler, he toed the party line when extreme pressure was exerted for the return of the Sudetenland and its German nationals by the Czechs to Germany." Many see Halder as a soldier of the older Prussian school variety. Like General Field Marshal von Manstein, an officer "bound to duty and oath."

For other insights regarding Halder's capabilities, see: Christian Hartmann and Sergei Slutsch, Franz Halder und die Kriegsvorbereitungen im Frühjahr 1939. Eine Ansprache des Generalstabschefs des Heeres in the journal Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (July 1997); Christian Hartmann, Halder: Generalstabschef Hitlers: 1939–1942, (1991), and Hitler's Generals, edited by Correlli Barnett.

The historians Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies II in The Myth of the Eastern Front (Cambridge University Press, 2008) argue that, after 1945, Halder played a key role in creating a false and mythic view of the Nazi-Soviet war in which the Wehrmacht was largely blameless for both Germany's military defeat and its war crimes.

Searle, Alaric. Wehrmacht Generals, West German Society, and the Debate on Rearmament, 1949–1959, Praeger Pub., 2003.

Notes

- ^ Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death, (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1996), 91.

- ^ Luise Jodl, Jenseits des Endes. Leben und Sterben des Generaloberst Alfred Jodl (Vienna: Molden Verlag, 1976), 30

- ^ Hitler Strikes Poland, pp. 22, 116 and 176

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 pages 470–472

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 471.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 pages 471–472.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 472.

- ^ a b c d e f Wheeler-Bennett page 474.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 474.

- ^ a b Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 474.

- ^ a b Frieser, Karl-Heinz and John T. Greenwood, "The Blitzkrieg Legend", Naval Institute Press, 2005, ISBN 1-59114-294-6

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 494.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 493.

- ^ a b c d e Wheeler-Bennett, page 493. Cite error: The named reference "wheeler493" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 pages 512–513.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967 page 513.

- ^ a b Hillgruber 1989, pp 95–96.

- ^ Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union", page 502

- ^ Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union", page 501

- ^ Barry A. Leach, "Halder: Colonel-General Franz Halder," in Hitler's Generals, ed. Correlli Barnett (New York: Grove Press, 1989), 122.

- ^ Hartmann, Christian: Halder. Generalstabschef Hitlers 1938–1942, Paderborn: Schoeningh 1991, ISBN 3-506-77484-0

- ^ "The Private War Journal of Generaloberst Franz Halder – Summary Guide". Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

References

- Burdick, Charles, Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf. (1988). The Halder War Diary 1939–1942. New York: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-302-2.

- Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union" pages 494–520 from The Nazi Holocaust Part 3 The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder Volume 2 edited by Michael Marrus, Westpoint: Meckler Press, 1989 ISBN 0-88736-255-9

- Halder, Franz, 1884–1972. War Journal of Franz Halder, 8 Volumes. [United States] : A.G. EUCOM, 1947. http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/search/collection/p4013coll8/searchterm/War%20journal%20of%20Franz%20Halder/field/title/mode/all/conn/and

- Taylor, Telford. Sword and Swastika. Chicago: Quadrangle, 1952. Print.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power The German Army In Politics 1918–1945, London: Macmillan, 1967.

External links

- 1884 births

- 1972 deaths

- People from Würzburg

- German diarists

- Military brats

- Wehrmacht generals

- German Resistance members

- German military personnel of World War I

- Military personnel of Bavaria

- People from the Kingdom of Bavaria

- Recipients of the Knight's Cross

- Knights of the House Order of Hohenzollern

- Recipients of the Military Merit Order (Bavaria), 4th class

- Knights 1st class of the Albert Order

- Recipients of the Military Merit Cross (Austria-Hungary)

- Recipients of the Cross of Honor

- Dachau concentration camp survivors

- Flossenbürg concentration camp survivors