Geometry

| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

Geometry (from the Template:Lang-grc; geo- "earth", -metron "measurement") is a branch of mathematics concerned with questions of shape, size, relative position of figures, and the properties of space. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is called a geometer. Geometry arose independently in a number of early cultures as a body of practical knowledge concerning lengths, areas, and volumes, with elements of formal mathematical science emerging in the West as early as Thales (6th century BC). By the 3rd century BC, geometry was put into an axiomatic form by Euclid, whose treatment—Euclidean geometry—set a standard for many centuries to follow.[1] Archimedes developed ingenious techniques for calculating areas and volumes, in many ways anticipating modern integral calculus. The field of astronomy, especially as it relates to mapping the positions of stars and planets on the celestial sphere and describing the relationship between movements of celestial bodies, served as an important source of geometric problems during the next one and a half millennia. In the classical world, both geometry and astronomy were considered to be part of the Quadrivium, a subset of the seven liberal arts considered essential for a free citizen to master.

The introduction of coordinates by René Descartes and the concurrent developments of algebra marked a new stage for geometry, since geometric figures such as plane curves could now be represented analytically in the form of functions and equations. This played a key role in the emergence of infinitesimal calculus in the 17th century. Furthermore, the theory of perspective showed that there is more to geometry than just the metric properties of figures: perspective is the origin of projective geometry. The subject of geometry was further enriched by the study of the intrinsic structure of geometric objects that originated with Euler and Gauss and led to the creation of topology and differential geometry.

In Euclid's time, there was no clear distinction between physical and geometrical space. Since the 19th-century discovery of non-Euclidean geometry, the concept of space has undergone a radical transformation and raised the question of which geometrical space best fits physical space. With the rise of formal mathematics in the 20th century, 'space' (whether 'point', 'line', or 'plane') lost its intuitive contents, so today one has to distinguish between physical space, geometrical spaces (in which 'space', 'point' etc. still have their intuitive meanings) and abstract spaces. Contemporary geometry considers manifolds, spaces that are considerably more abstract than the familiar Euclidean space, which they only approximately resemble at small scales. These spaces may be endowed with additional structure which allow one to speak about length. Modern geometry has many ties to physics as is exemplified by the links between pseudo-Riemannian geometry and general relativity. One of the youngest physical theories, string theory, is also very geometric in flavour.

While the visual nature of geometry makes it initially more accessible than other mathematical areas such as algebra or number theory, geometric language is also used in contexts far removed from its traditional, Euclidean provenance (for example, in fractal geometry and algebraic geometry).[2]

Overview

Because the recorded development of geometry spans more than two millennia, perceptions of what constitutes geometry have evolved throughout the ages:

Practical geometry

Geometry originated as a practical science concerned with surveys, measurements, areas, and volumes. Among other highlights, notable accomplishments include formulas for lengths, areas and volumes, such as the Pythagorean theorem, circumference and area of a circle, area of a triangle, volume of a cylinder, sphere, and a pyramid. A method of computing certain inaccessible distances or heights based on similarity of geometric figures is attributed to Thales. The development of astronomy led to the emergence of trigonometry and spherical trigonometry, together with the attendant computational techniques.

Axiomatic geometry

Euclid took a more abstract approach in his Elements, one of the most influential books ever written. Euclid introduced certain axioms, or postulates, expressing primary or self-evident properties of points, lines, and planes. He proceeded to rigorously deduce other properties by mathematical reasoning. The characteristic feature of Euclid's approach to geometry was its rigor, and it has come to be known as axiomatic or synthetic geometry. At the start of the 19th century, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky (1792–1856), János Bolyai (1802–1860) and Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) and others led to a revival of interest in this discipline, and in the 20th century, David Hilbert (1862–1943) employed axiomatic reasoning in an attempt to provide a modern foundation of geometry.

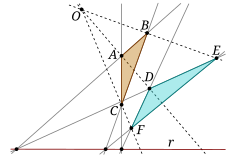

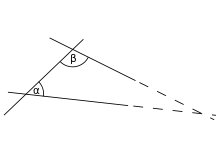

Geometric constructions

Classical geometers paid special attention to constructing geometric objects that had been described in some other way. Classically, the only instruments allowed in geometric constructions are the compass and straightedge. Also, every construction had to be complete in a finite number of steps. However, some problems turned out to be difficult or impossible to solve by these means alone, and ingenious constructions using parabolas and other curves, as well as mechanical devices, were found.

Numbers in geometry

In ancient Greece the Pythagoreans considered the role of numbers in geometry. However, the discovery of incommensurable lengths, which contradicted their philosophical views, made them abandon abstract numbers in favor of concrete geometric quantities, such as length and area of figures. Numbers were reintroduced into geometry in the form of coordinates by Descartes, who realized that the study of geometric shapes can be facilitated by their algebraic representation, and for whom the Cartesian plane is named. Analytic geometry applies methods of algebra to geometric questions, typically by relating geometric curves to algebraic equations. These ideas played a key role in the development of calculus in the 17th century and led to the discovery of many new properties of plane curves. Modern algebraic geometry considers similar questions on a vastly more abstract level.

Geometry of position

Even in ancient times, geometers considered questions of relative position or spatial relationship of geometric figures and shapes. Some examples are given by inscribed and circumscribed circles of polygons, lines intersecting and tangent to conic sections, the Pappus and Menelaus configurations of points and lines. In the Middle Ages, new and more complicated questions of this type were considered: What is the maximum number of spheres simultaneously touching a given sphere of the same radius (kissing number problem)? What is the densest packing of spheres of equal size in space (Kepler conjecture)? Most of these questions involved 'rigid' geometrical shapes, such as lines or spheres. Projective, convex, and discrete geometry are three sub-disciplines within present day geometry that deal with these types of questions.

Leonhard Euler, in studying problems like the Seven Bridges of Königsberg, considered the most fundamental properties of geometric figures based solely on shape, independent of their metric properties. Euler called this new branch of geometry geometria situs (geometry of place), but it is now known as topology. Topology grew out of geometry, but turned into a large independent discipline. It does not differentiate between objects that can be continuously deformed into each other. The objects may nevertheless retain some geometry, as in the case of hyperbolic knots.

Geometry beyond Euclid

In the nearly two thousand years since Euclid, while the range of geometrical questions asked and answered inevitably expanded, the basic understanding of space remained essentially the same. Immanuel Kant argued that there is only one, absolute, geometry, which is known to be true a priori by an inner faculty of mind: Euclidean geometry was synthetic a priori.[3] This dominant view was overturned by the revolutionary discovery of non-Euclidean geometry in the works of Bolyai, Lobachevsky, and Gauss (who never published his theory). They demonstrated that ordinary Euclidean space is only one possibility for development of geometry. A broad vision of the subject of geometry was then expressed by Riemann in his 1867 inauguration lecture Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen (On the hypotheses on which geometry is based),[4] published only after his death. Riemann's new idea of space proved crucial in Einstein's general relativity theory, and Riemannian geometry, that considers very general spaces in which the notion of length is defined, is a mainstay of modern geometry.

Dimension

Where the traditional geometry allowed dimensions 1 (a line), 2 (a plane) and 3 (our ambient world conceived of as three-dimensional space), mathematicians have used higher dimensions for nearly two centuries. Dimension has gone through stages of being any natural number n, possibly infinite with the introduction of Hilbert space, and any positive real number in fractal geometry. Dimension theory is a technical area, initially within general topology, that discusses definitions; in common with most mathematical ideas, dimension is now defined rather than an intuition. Connected topological manifolds have a well-defined dimension; this is a theorem (invariance of domain) rather than anything a priori.

The issue of dimension still matters to geometry, in the absence of complete answers to classic questions. Dimensions 3 of space and 4 of space-time are special cases in geometric topology. Dimension 10 or 11 is a key number in string theory. Research may bring a satisfactory geometric reason for the significance of 10 and 11 dimensions.

Symmetry

The theme of symmetry in geometry is nearly as old as the science of geometry itself. Symmetric shapes such as the circle, regular polygons and platonic solids held deep significance for many ancient philosophers and were investigated in detail before the time of Euclid. Symmetric patterns occur in nature and were artistically rendered in a multitude of forms, including the graphics of M. C. Escher. Nonetheless, it was not until the second half of 19th century that the unifying role of symmetry in foundations of geometry was recognized. Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed that, in a very precise sense, symmetry, expressed via the notion of a transformation group, determines what geometry is. Symmetry in classical Euclidean geometry is represented by congruences and rigid motions, whereas in projective geometry an analogous role is played by collineations, geometric transformations that take straight lines into straight lines. However it was in the new geometries of Bolyai and Lobachevsky, Riemann, Clifford and Klein, and Sophus Lie that Klein's idea to 'define a geometry via its symmetry group' proved most influential. Both discrete and continuous symmetries play prominent roles in geometry, the former in topology and geometric group theory, the latter in Lie theory and Riemannian geometry.

A different type of symmetry is the principle of duality in projective geometry (see Duality (projective geometry)) among other fields. This meta-phenomenon can roughly be described as follows: in any theorem, exchange point with plane, join with meet, lies in with contains, and you will get an equally true theorem. A similar and closely related form of duality exists between a vector space and its dual space.

History

The earliest recorded beginnings of geometry can be traced to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt in the 2nd millennium BC.[5][6] Early geometry was a collection of empirically discovered principles concerning lengths, angles, areas, and volumes, which were developed to meet some practical need in surveying, construction, astronomy, and various crafts. The earliest known texts on geometry are the Egyptian Rhind Papyrus (2000–1800 BC) and Moscow Papyrus (c. 1890 BC), the Babylonian clay tablets such as Plimpton 322 (1900 BC). For example, the Moscow Papyrus gives a formula for calculating the volume of a truncated pyramid, or frustum.[7] Later clay tablets (350–50 BC) demonstrate that Babylonian astronomers implemented trapezoid procedures for computing Jupiter's position and motion within time-velocity space. These geometric procedures anticipated the Oxford Calculators, including the mean speed theorem, by 14 centuries.[8] South of Egypt the ancient Nubians established a system of geometry including early versions of sun clocks.[9][10]

In the 7th century BC, the Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of pyramids and the distance of ships from the shore. He is credited with the first use of deductive reasoning applied to geometry, by deriving four corollaries to Thales' Theorem.[11] Pythagoras established the Pythagorean School, which is credited with the first proof of the Pythagorean theorem,[12] though the statement of the theorem has a long history[13][14] Eudoxus (408–c. 355 BC) developed the method of exhaustion, which allowed the calculation of areas and volumes of curvilinear figures,[15] as well as a theory of ratios that avoided the problem of incommensurable magnitudes, which enabled subsequent geometers to make significant advances. Around 300 BC, geometry was revolutionized by Euclid, whose Elements, widely considered the most successful and influential textbook of all time,[16] introduced mathematical rigor through the axiomatic method and is the earliest example of the format still used in mathematics today, that of definition, axiom, theorem, and proof. Although most of the contents of the Elements were already known, Euclid arranged them into a single, coherent logical framework.[17] The Elements was known to all educated people in the West until the middle of the 20th century and its contents are still taught in geometry classes today.[18] Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) of Syracuse used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, and gave remarkably accurate approximations of Pi.[19] He also studied the spiral bearing his name and obtained formulas for the volumes of surfaces of revolution.

Indian mathematicians also made many important contributions in geometry. The Satapatha Brahmana (3rd century BC) contains rules for ritual geometric constructions that are similar to the Sulba Sutras.[20] According to (Hayashi 2005, p. 363), the Śulba Sūtras contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians. They contain lists of Pythagorean triples,[21] which are particular cases of Diophantine equations.[22] In the Bakhshali manuscript, there is a handful of geometric problems (including problems about volumes of irregular solids). The Bakhshali manuscript also "employs a decimal place value system with a dot for zero."[23] Aryabhata's Aryabhatiya (499) includes the computation of areas and volumes. Brahmagupta wrote his astronomical work Brāhma Sphuṭa Siddhānta in 628. Chapter 12, containing 66 Sanskrit verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain).[24] In the latter section, he stated his famous theorem on the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral. Chapter 12 also included a formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a generalization of Heron's formula), as well as a complete description of rational triangles (i.e. triangles with rational sides and rational areas).[24]

In the Middle Ages, mathematics in medieval Islam contributed to the development of geometry, especially algebraic geometry[25] and geometric algebra.[26] Al-Mahani (b. 853) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra.[27] Thābit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin) (836–901) dealt with arithmetic operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities, and contributed to the development of analytic geometry.[28] Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) found geometric solutions to cubic equations.[29] The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Omar Khayyam and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi on quadrilaterals, including the Lambert quadrilateral and Saccheri quadrilateral, were early results in hyperbolic geometry, and along with their alternative postulates, such as Playfair's axiom, these works had a considerable influence on the development of non-Euclidean geometry among later European geometers, including Witelo (c. 1230–c. 1314), Gersonides (1288–1344), Alfonso, John Wallis, and Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri.[30]

In the early 17th century, there were two important developments in geometry. The first was the creation of analytic geometry, or geometry with coordinates and equations, by René Descartes (1596–1650) and Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665). This was a necessary precursor to the development of calculus and a precise quantitative science of physics. The second geometric development of this period was the systematic study of projective geometry by Girard Desargues (1591–1661). Projective geometry is a geometry without measurement or parallel lines, just the study of how points are related to each other.

Two developments in geometry in the 19th century changed the way it had been studied previously. These were the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, János Bolyai and Carl Friedrich Gauss and of the formulation of symmetry as the central consideration in the Erlangen Programme of Felix Klein (which generalized the Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries). Two of the master geometers of the time were Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866), working primarily with tools from mathematical analysis, and introducing the Riemann surface, and Henri Poincaré, the founder of algebraic topology and the geometric theory of dynamical systems. As a consequence of these major changes in the conception of geometry, the concept of "space" became something rich and varied, and the natural background for theories as different as complex analysis and classical mechanics.

Contemporary geometry

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry has become closely connected with computational geometry, computer graphics, convex geometry, incidence geometry, finite geometry, discrete geometry, and some areas of combinatorics. Attention was given to further work on Euclidean geometry and the Euclidean groups by crystallography and the work of H. S. M. Coxeter, and can be seen in theories of Coxeter groups and polytopes. Geometric group theory is an expanding area of the theory of more general discrete groups, drawing on geometric models and algebraic techniques.

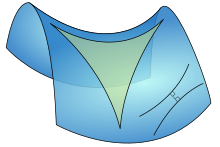

Differential geometry

Differential geometry has been of increasing importance to mathematical physics due to Einstein's general relativity postulation that the universe is curved. Contemporary differential geometry is intrinsic, meaning that the spaces it considers are smooth manifolds whose geometric structure is governed by a Riemannian metric, which determines how distances are measured near each point, and not a priori parts of some ambient flat Euclidean space.

Topology and geometry

The field of topology, which saw massive development in the 20th century, is in a technical sense a type of transformation geometry, in which transformations are homeomorphisms. This has often been expressed in the form of the dictum 'topology is rubber-sheet geometry'. Contemporary geometric topology and differential topology, and particular subfields such as Morse theory, would be counted by most mathematicians as part of geometry. Algebraic topology and general topology have gone their own ways.

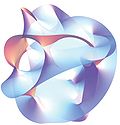

Algebraic geometry

The field of algebraic geometry is the modern incarnation of the Cartesian geometry of co-ordinates. From late 1950s through mid-1970s it had undergone major foundational development, largely due to work of Jean-Pierre Serre and Alexander Grothendieck. This led to the introduction of schemes and greater emphasis on topological methods, including various cohomology theories. One of seven Millennium Prize problems, the Hodge conjecture, is a question in algebraic geometry.

The study of low-dimensional algebraic varieties, algebraic curves, algebraic surfaces and algebraic varieties of dimension 3 ("algebraic threefolds"), has been far advanced. Gröbner basis theory and real algebraic geometry are among more applied subfields of modern algebraic geometry. Arithmetic geometry is an active field combining algebraic geometry and number theory. Other directions of research involve moduli spaces and complex geometry. Algebro-geometric methods are commonly applied in string and brane theory.

See also

Lists

- List of geometers

- List of formulas in elementary geometry

- List of geometry topics

- List of important publications in geometry

- List of mathematics articles

Related topics

- Descriptive geometry

- Finite geometry

- Flatland, a book written by Edwin Abbott Abbott about two- and three-dimensional space, to understand the concept of four dimensions

- Interactive geometry software

Other fields

Notes

- ^ Martin J. Turner,Jonathan M. Blackledge,Patrick R. Andrews (1998). Fractal geometry in digital imaging. Academic Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-12-703970-8

- ^ It is quite common in algebraic geometry to speak about geometry of algebraic varieties over finite fields, possibly singular. From a naïve perspective, these objects are just finite sets of points, but by invoking powerful geometric imagery and using well developed geometric techniques, it is possible to find structure and establish properties that make them somewhat analogous to the ordinary spheres or cones.

- ^ Kline (1972) "Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times", Oxford University Press, p. 1032. Kant did not reject the logical (analytic a priori) possibility of non-Euclidean geometry, see Jeremy Gray, "Ideas of Space Euclidean, Non-Euclidean, and Relativistic", Oxford, 1989; p. 85. Some have implied that, in light of this, Kant had in fact predicted the development of non-Euclidean geometry, cf. Leonard Nelson, "Philosophy and Axiomatics," Socratic Method and Critical Philosophy, Dover, 1965, p. 164.

- ^ "Ueber die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen".

- ^ J. Friberg, "Methods and traditions of Babylonian mathematics. Plimpton 322, Pythagorean triples, and the Babylonian triangle parameter equations", Historia Mathematica, 8, 1981, pp. 277—318.

- ^ Neugebauer, Otto (1969) [1957]. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity (2 ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2. Chap. IV "Egyptian Mathematics and Astronomy", pp. 71–96.

- ^ (Boyer 1991, "Egypt" p. 19) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ Ossendrijver, Mathieu (29 January 2016). "Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter's position from the area under a time-velocity graph". Science. 351 (6272): 482–484. doi:10.1126/science.aad8085. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. Vol. 84, 1998 Gnomons at Meroë and Early Trigonometry. pg. 171

- ^ Slayman, Andrew (27 May 1998). "Neolithic Skywatchers". Archaeology Magazine Archive.

- ^ (Boyer 1991, "Ionia and the Pythagoreans" p. 43) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ Eves, Howard, An Introduction to the History of Mathematics, Saunders, 1990, ISBN 0-03-029558-0.

- ^ Kurt Von Fritz (1945). "The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum". The Annals of Mathematics.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ James R. Choike (1980). "The Pentagram and the Discovery of an Irrational Number". The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ (Boyer 1991, "The Age of Plato and Aristotle" p. 92) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ (Boyer 1991, "Euclid of Alexandria" p. 119) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ (Boyer 1991, "Euclid of Alexandria" p. 104) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoyer1991 (help)

- ^ Howard Eves, An Introduction to the History of Mathematics, Saunders, 1990, ISBN 0-03-029558-0 p. 141: "No work, except The Bible, has been more widely used...."

- ^ O'Connor, J.J. and Robertson, E.F. (February 1996). "A history of calculus". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ (Staal 1999)[full citation needed]

- ^ Pythagorean triples are triples of integers with the property: . Thus, , , etc.

- ^ (Cooke 2005, p. 198): "The arithmetic content of the Śulva Sūtras consists of rules for finding Pythagorean triples such as (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (8, 15, 17), and (12, 35, 37). It is not certain what practical use these arithmetic rules had. The best conjecture is that they were part of religious ritual. A Hindu home was required to have three fires burning at three different altars. The three altars were to be of different shapes, but all three were to have the same area. These conditions led to certain "Diophantine" problems, a particular case of which is the generation of Pythagorean triples, so as to make one square integer equal to the sum of two others."

- ^ (Hayashi 2005, p. 371)

- ^ a b (Hayashi 2003, pp. 121–122)

- ^ R. Rashed (1994), The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra, p. 35 London

- ^ Boyer (1991). "The Arabic Hegemony". A History of Mathematics. pp. 241–242.

Omar Khayyam (ca. 1050–1123), the "tent-maker," wrote an Algebra that went beyond that of al-Khwarizmi to include equations of third degree. Like his Arab predecessors, Omar Khayyam provided for quadratic equations both arithmetic and geometric solutions; for general cubic equations, he believed (mistakenly, as the 16th century later showed), arithmetic solutions were impossible; hence he gave only geometric solutions. The scheme of using intersecting conics to solve cubics had been used earlier by Menaechmus, Archimedes, and Alhazan, but Omar Khayyam took the praiseworthy step of generalizing the method to cover all third-degree equations (having positive roots). .. For equations of higher degree than three, Omar Khayyam evidently did not envision similar geometric methods, for space does not contain more than three dimensions, ... One of the most fruitful contributions of Arabic eclecticism was the tendency to close the gap between numerical and geometric algebra. The decisive step in this direction came much later with Descartes, but Omar Khayyam was moving in this direction when he wrote, "Whoever thinks algebra is a trick in obtaining unknowns has thought it in vain. No attention should be paid to the fact that algebra and geometry are different in appearance. Algebras are geometric facts which are proved."

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Al-Mahani", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Al-Sabi Thabit ibn Qurra al-Harrani", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Omar Khayyam", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 2, p. 447–494 [470], Routledge, London and New York:

"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam, and al-Tusi, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the 19th century. In essence, their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered, assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries. Their other proposals showed that various geometric statements were equivalent to the Euclidean postulate V. It is extremely important that these scholars established the mutual connection between this postulate and the sum of the angles of a triangle and a quadrangle. By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts. The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines – made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the 13th century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir) – was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources. The proofs put forward in the 14th century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration. Above, we have demonstrated that Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid had stimulated both J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines."

Sources

- Boyer, C. B. (1991) [1989]. A History of Mathematics (Second edition, revised by Uta C. Merzbach ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nikolai I. Lobachevsky, Pangeometry, translator and editor: A. Papadopoulos, Heritage of European Mathematics Series, Vol. 4, European Mathematical Society, 2010.

Further reading

- Jay Kappraff, A Participatory Approach to Modern Geometry, 2014, World Scientific Publishing, ISBN 978-981-4556-70-5.

- Leonard Mlodinow, Euclid's Window – The Story of Geometry from Parallel Lines to Hyperspace, UK edn. Allen Lane, 1992.

External links

- A geometry course from Wikiversity

- Unusual Geometry Problems

- The Math Forum — Geometry

- Nature Precedings — Pegs and Ropes Geometry at Stonehenge

- The Mathematical Atlas — Geometric Areas of Mathematics

- "4000 Years of Geometry", lecture by Robin Wilson given at Gresham College, 3 October 2007 (available for MP3 and MP4 download as well as a text file)

- Finitism in Geometry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Geometry Junkyard

- Interactive geometry reference with hundreds of applets

- Dynamic Geometry Sketches (with some Student Explorations)

- Geometry classes at Khan Academy