Glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate between glacial periods. The last glacial period ended about 15,000 years ago.[1] The Holocene epoch is the current interglacial. A time when there are no glaciers on Earth is considered a greenhouse climate state.[2][3][4]

Quaternary ice age

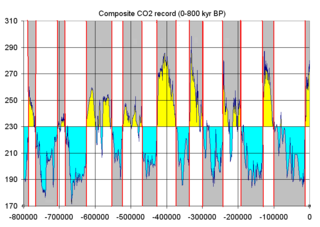

Within the Quaternary glaciation (1.8 Ma to present), there have been a number of glacials and interglacials.

Last glacial period

The last glacial period was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age, occurring in the Pleistocene epoch, which began about 110,000 years ago and ended about 15,000 years ago.[1] The glaciations that occurred during this glacial period covered many areas of the Northern Hemisphere and have different names, depending on their geographic distributions: Wisconsin (in North America), Devensian (in Great Britain), Midlandian (in Ireland), Würm (in the Alps), Weichsel (in northern central Europe), Dali (in East China), Beiye (in North China), Taibai (in Shaanxi) Luojishan (in Southwest Sichuan), Zagunao (in Northwest Sichuan), Tianchi (in Tianshan Mountains) Qomolangma (in Himalaya), and Llanquihue (in Chile). The glacial advance reached its maximum extent about 18,000 BP. In Europe, the ice sheet reached northern Germany.

Next glacial period

Since orbital variations are predictable,[5] computer models that relate orbital variations to climate can predict future climate possibilities. Two caveats are necessary: that anthropogenic effects (human-assisted global warming) are likely to exert a larger influence over the short term; and that the mechanism by which orbital forcing influences climate is not well understood. Work by Berger and Loutre suggests that the current warm climate may last another 50,000 years.[6]

See also

- Climate

- Cyclostratigraphy

- Geologic time scale

- Glacial history of Minnesota

- Glacier

- Greenhouse and Icehouse Earth

- Ice age

- Interglacial and Interstadial periods

- Last Glacial Maximum

- last glacial period

- Milankovitch cycles

- Precession (astronomy)

- Quaternary glaciation

- Snowball Earth

- Timeline of glaciation

- Yarkovsky effect

- YORP effect

References

- ^ a b J. Severinghaus; E. Brook (1999). "Abrupt Climate Change at the End of the Last Glacial Period Inferred from Trapped Air in Polar Ice". Science. 286 (5441): 930–4. doi:10.1126/science.286.5441.930. PMID 10542141.

- ^ Bralower, T.J.; Premoli Silva, I.; Malone, M.J. (2006). [Abstract Summary Leg 198 Synthesis : A Remarkable 120-m.y. Record of Climate and Oceanography from Shatsky Rise, Northwest Pacific Ocean]. Proceedings of the Ocean drilling program. p. 47. doi:10.2973/odp.proc.ir.198.2002. ISSN 1096-2158. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Christopher M. Fedo; Grant M. Young; H. Wayne Nesbitt (1997). "Paleoclimatic control on the composition of the Paleoproterozoic Serpent Formation, Huronian Supergroup, Canada: a greenhouse to icehouse transition". Precambrian Research. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/S0301-9268(97)00049-1.

- ^ Miriam E. Katz; Kenneth G. Miller; James D. Wright; Bridget S. Wade; James V. Browning; Benjamin S. Cramer; Yair Rosenthal (2008). "Stepwise transition from the Eocene greenhouse to the Oligocene icehouse". Nature Geoscience. Nature. doi:10.1038/ngeo179.

- ^ F. Varadi; B. Runnegar; M. Ghil (2003). "Successive Refinements in Long-Term Integrations of Planetary Orbits" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 592: 620–630. Bibcode:2003ApJ...592..620V. doi:10.1086/375560.

- ^ Berger A, Loutre MF (2002). "Climate: An exceptionally long interglacial ahead?". Science. 297 (5585): 1287–8. doi:10.1126/science.1076120. PMID 12193773.