Religious cosmology

Religious cosmology is an explanation of the origin, evolution, and eventual fate of the universe from a religious perspective. This may include beliefs on origin in the form of a creation myth, subsequent evolution, current organizational form and nature, and eventual fate or destiny. There are various traditions in religion or religious mythology asserting how and why everything is the way it is and the significance of it all. Religious cosmologies describe the spatial lay-out of the universe in terms of the world in which people typically dwell as well as other dimensions, such as the seven dimensions of religion; these are ritual, experiential and emotional, narrative and mythical, doctrinal, ethical, social, and material.[1]

Religious mythologies may include descriptions of an act or process of creation by a creator deity or a larger pantheon of deities, explanations of the transformation of chaos into order, or the assertion that existence is a matter of endless cyclical transformations. Religious cosmology differs from a strictly scientific cosmology informed by contemporary astronomy, physics, and similar fields, and may differ in conceptualizations of the world's physical structure and place in the universe, its creation, and forecasts or predictions on its future.

The scope of religious cosmology is more inclusive than a strictly scientific cosmology (physical cosmology and quantum cosmology) in that religious cosmology is not limited to experiential observation, testing of hypotheses, and proposals of theories; for example, religious cosmology may explain why everything is the way it is or seems to be the way it is and prescribing what humans should do in context. Variations in religious cosmology include Zoroastrian cosmology, those such as from India Buddhism, Hindu, and Jain; the religious beliefs of China, Chinese Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, Japan's Shintoisim and the beliefs of the Abrahamic faiths, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Religious cosmologies have often developed into the formal logics of metaphysical systems, such as Platonism, Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Taoism, Kabbalah, Wuxing or the great chain of being.

Zoroastrian

[edit]In Zoroastrian cosmology, universe is the manifestation of a cosmic conflict between Existence and non-existence, Good and evil and light and darkness which spans over a period of 12000 years. It is subdivided into four equal periods of 3000 years each. The first period is known as Infinite Time. During this period the good and the evil remained in perfect balance in their respective spheres. For 3000 years Ahura Mazda dwelt in the region of light, while his opponent Ahirman or Angra Mainyu, the evil spirit, remained confined to the region of darkness. A great Void separated them both. At the end of the first period, Ahirman crossed the void and attacked Ahura Mazda. Knowing that the battle would continue forever, Ahura Mazda recited Ahuna Vairya, the most sacred hymn of Avesta and repelled him back. Having lost the battle, Angra Mainyu withdrew hastily into his dark world and remained there for another 3000 years. During this interlude, Ahura Mazda brings forth the entire creation. He creates the six Amesha Spentas or the Holy Immortals and several angel spirits or Yazatas. He brought forth the primeval Ox and the primeval man (Gayomart). Then he creates the material creation such as water, air, earth and the metals.[2]

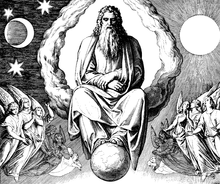

Biblical cosmology and Abrahamic faiths

[edit]The universe of the ancient Israelites was made up of a flat disc-shaped Earth floating on water, heaven above, underworld below.[3] Humans inhabited Earth during life and the underworld after death, and the underworld was morally neutral;[4] only in Hellenistic times (after c.330 BC) did Jews begin to adopt the Greek idea that it would be a place of punishment for misdeeds, and that the righteous would enjoy an afterlife in heaven.[5] In this period too the older three-level cosmology was widely replaced by the Greek concept of a spherical Earth suspended in space at the centre of a number of concentric heavens.[3] The belief that God created matter from nothing is called creatio ex nihilo (as opposed to creatio ex materia). It is the accepted orthodoxy of most denominations of Judaism and Christianity. Most denominations of Christianity and Judaism believe that a single, uncreated God was responsible for the creation of the cosmos.

In his 2023 apostolic exhortation, Laudate Deum, Pope Francis outlines several ways in which the human relationship with the created cosmos might be understood:

- the world that surrounds us can be treated as "an object of exploitation, unbridled use and unlimited ambition" or "a mere 'setting' in which we can develop our lives";

- the human being is extraneous, a foreign element capable only of harming the environment;

- human beings "are part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it". This is the interpretation he supports.[6]

Islam teaches that God created the universe, including Earth's physical environment and human beings. The highest goal is to visualize the cosmos as a book of symbols for meditation and contemplation for spiritual upliftment or as a prison from which the human soul must escape to attain true freedom in the spiritual journey to God.[8]

Indian

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]In Buddhism, like other Indian religions, there is no ultimate beginning nor final end to the universe. It considers all existence as eternal, and believes there is no creator god.[9][10] Buddhism views the universe as impermanent and always in flux. This cosmology is the foundation of its Samsara theory, that evolved over time the mechanistic details on how the wheel of mundane existence works over the endless cycles of rebirth and redeath.[11] In early Buddhist traditions, Saṃsāra cosmology consisted of five realms through which wheel of existence recycled.[12] This included hells (niraya), hungry ghosts (pretas), animals (tiryak), humans (manushya), and gods (devas, heavenly).[12][11][13] In latter traditions, this list grew to a list of six realms of rebirth, adding demi-gods (asuras).[12][14] The "hungry ghost, heavenly, hellish realms" respectively formulate the ritual, literary and moral spheres of many contemporary Buddhist traditions.[12][11]

According to Akira Sadakata, the Buddhist cosmology is far more complex and uses extraordinarily larger numbers than those found in Vedic and post-Vedic Hindu traditions.[15] It also shares many ideas and concepts, such as those about Mount Meru.[16][17] The Buddhist thought holds that the six cosmological realms are interconnected, and everyone cycles life after life, through these realms, because of a combination of ignorance, desires and purposeful karma, or ethical and unethical actions.[12][11]

Hindu

[edit]The Hindu cosmology, like the Buddhist and Jain cosmology, considers all existence as cyclic.[18][19] With its ancient roots, Hindu texts propose and discuss numerous cosmological theories. Hindu culture accepts this diversity in cosmological ideas and has lacked a single mandatory view point even in its oldest known Vedic scriptures, the Rigveda.[20] Alternate theories include a universe cyclically created and destroyed by god, or goddess, or no creator at all, or a golden egg or womb (Hiranyagarbha), or self-created multitude of universes with enormous lengths and time scales.[20][21][22] The Vedic literature includes a number of cosmology speculations, one of which questions the origin of the cosmos and is called the Nasadiya sukta:

Neither being (sat) nor non-being was as yet. What was concealed?

And where? And in whose protection?…Who really knows?

Who can declare it? Whence was it born, and whence came this creation?

The devas (gods) were born later than this world's creation,

so who knows from where it came into existence? None can know from where

creation has arisen, and whether he has or has not produced it.

He who surveys it in the highest heavens,

He alone knows or perhaps He does not know."

Time is conceptualized as a cyclic Yuga with trillions of years.[26] In some models, Mount Meru plays a central role.[27][28]

Beyond its creation, Hindu cosmology posits divergent theories on the structure of the universe, from being 3 lokas to 12 lokas (worlds) which play a part in its theories about rebirth, samsara and karma.[29][30][31]

The complex cosmological speculations found in Hinduism and other Indian religions, states Bolton, is not unique and are also found in Greek, Roman, Irish and Babylonian mythologies, where each age becomes more sinful and of suffering.[32][33]

Jain

[edit]Jain cosmology considers the loka, or universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, having no beginning or an end.[34] Jain texts describe the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is narrow at the top, broad at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom.[35]

Mahāpurāṇa of Ācārya Jinasena is famous for this quote:

Some foolish men declare that a creator made the world. The doctrine that the world was created is ill advised and should be rejected. If God created the world, where was he before the creation? If you say he was transcendent then and needed no support, where is he now? How could God have made this world without any raw material? If you say that he made this first, and then the world, you are faced with an endless regression.

Chinese

[edit]There is a "primordial universe" Wuji (philosophy), and Hongjun Laozu, water or qi.[36][37] It transformed into Taiji then multiplied into everything known as the Wuxing.[38][39] The Pangu legend tells a formless chaos coalesced into a cosmic egg. Pangu emerged (or woke up) and separated Yin from Yang with a swing of his giant axe, creating the Earth (murky Yin) and the Sky (clear Yang). To keep them separated, Pangu stood between them and pushed up the Sky. After Pangu died, he became everything.

Gnosticism

[edit]Gnostic teachings were contemporary with those of Neoplatonism. Gnosticism is an imprecise label, covering monistic as well as dualistic conceptions. Usually the higher worlds of Light, called the Pleroma or "fullness", are radically distinct from the lower world of Matter. The emanation of the Pleroma and its godheads (called Aeons) is described in detail in the various Gnostic tracts, as is the pre-creation crisis (a cosmic equivalent to the "fall" in Christian thought) from which the material world comes about, and the way that the divine spark can attain salvation.[40]

Serer religion

[edit]Serer religion posits that, Roog, the creator deity, is the point of departure and conclusion.[41] As farming people, trees play an important role in Serer religious cosmology and creation mythology. The Serer high priests and priestesses (the Saltigues) chart the star Sirius, known as "Yoonir" in the Serer language and some of the Cangin languages. This star enables them to give accurate information as to when Serer farmers should start planting seeds among other things relevant to Serer lives and Serer country. "Yoonir" is the symbol of the universe in Serer cosmology and creation mythology.[42][41]

A similar set of beliefs related also to Sirius has been observed among Dogon people of Mali.[43]

See also

[edit]- Axis mundi

- Baháʼí cosmology

- Big Bang § Pre–Big Bang cosmology

- Cosmology of The Urantia Book

- Chinese creation myth

- Dogon people § Dogon astronomical beliefs

- Greek mythology § Origins of the world and the gods

- History of the center of the Universe

- Japanese creation myth

- Mandaean cosmology

- Raëlian beliefs and practices § Structure of the Universe

- Somnium Scipionis – Sixth book of Cicero's "De re publica"

- Worship of heavenly bodies

- Zoroastrian cosmology

References

[edit]- ^ Tucker, Mary Evelyn (1998). "Religious Dimensions of Confucianism: Cosmology and Cultivation". Philosophy East and West. 48 (1): 5–45. doi:10.2307/1399924. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 1399924.

- ^ "The Bundahishn ("Creation"), or Knowledge from the Zand".

- ^ a b Aune 2003, p. 119

- ^ Wright 2002, pp. 117, 124–125

- ^ Lee 2010, pp. 77–78

- ^ Pope Francis (2023), Laudate Deum, paragraphs 25-26, accessed 7 June 2024

- ^ Zakariya al-Qazwini. ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt (The Wonders of Creation). Original published in 1553 AD

- ^ "Cosmology". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012.

- ^ Blackburn, Anne M.; Samuels, Jeffrey (2003). Approaching the Dhamma: Buddhist Texts and Practices in South and Southeast Asia. Pariyatti. pp. 128–146. ISBN 978-1-928706-19-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2nd ed.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–38, ISBN 978-0-521-67674-8

- ^ a b c d Kevin Trainor (2004). Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-19-517398-7.

- ^ a b c d e Jeff Wilson (2010). Saṃsāra and Rebirth, in Buddhism. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780195393521-0141. ISBN 978-0-19-539352-1.

- ^ Robert DeCaroli (2004). Haunting the Buddha: Indian Popular Religions and the Formation of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 94–103. ISBN 978-0-19-803765-1.

- ^ Akira Sadakata (1997). Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins. Kōsei Publishing 佼成出版社, Tokyo. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-4-333-01682-2.

- ^ Akira Sadakata (1997). Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins. 佼成出版社. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-4-333-01682-2.

- ^ Akira Sadakata (1997). Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins. 佼成出版社. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-4-333-01682-2.

- ^ Randy Kloetzli (1983). Buddhist Cosmology: From Single World System to Pure Land: Science and Theology in the Images of Motion and Light. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 13, 23–31. ISBN 978-0-89581-955-0.

- ^ George Michell; Philip H. Davies (1989). The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu. Penguin. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-14-008144-2.

- ^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2012). Hindu World. Routledge. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-134-60875-1.

- ^ a b James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ^ Randall L. Nadeau (2014). Asian Religions: A Cultural Perspective. Wiley. pp. 133–137. ISBN 978-1-118-47195-1.

- ^ Charles Lanman, To the unknown god, Book X, Hymn 121, Rigveda, The Sacred Books of the East Volume IX: India and Brahmanism, Editor: Max Muller, Oxford, pages 46–50

- ^ Kenneth Kramer (January 1986). World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions. Paulist Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-8091-2781-8.

- ^ David Christian (1 September 2011). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-520-95067-2.

- ^ Robert N. Bellah (2011). Religion in Human Evolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 510–511. ISBN 978-0-674-06309-9.

- ^ Graham Chapman; Thackwray Driver (2002). Timescales and Environmental Change. Routledge. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-134-78754-8.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 123–125, 130–132. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

- ^ John E. Mitchiner (2000). Traditions Of The Seven Rsis. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 141–144. ISBN 978-81-208-1324-3.

- ^ Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. SUNY Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7914-0799-8.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ John A. Grimes (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7914-3067-5.

- ^ Robert Bolton (2001). The Order of the Ages: World History in the Light of a Universal Cosmogony. Sophia Perennis. pp. 64–78. ISBN 978-0-900588-31-0.

- ^ Donald Alexander Mackenzie (1915). Mythology of the Babylonian People. Bracken Books. pp. 310–314. ISBN 978-0-09-185145-3.

- ^ "This universe is not created nor sustained by anyone; It is self sustaining, without any base or support" "Nishpaadito Na Kenaapi Na Dhritah Kenachichch Sah Swayamsiddho Niradhaaro Gagane Kimtvavasthitah" [Yogaśāstra of Ācārya Hemacandra 4.106] Tr by Dr. A. S. Gopani

- ^ See Hemacandras description of universe in Yogaśāstra "…Think of this loka as similar to man standing akimbo…"4.103-6

- ^ 《太一生水》之混沌神話

- ^ 道教五方三界諸天「氣數」說探源

- ^ 太一與三一

- ^ 太極初探

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 396. ISBN 1-4381-3026-0.

- ^ a b Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji Madiya, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition (Louvain, Belgium). ISBN 0-660-15965-1. pp 5, 27, 115

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, "La civilisation sereer : Pangool", vol. 2, Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal, (1990) pp 20–21, 149–155, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Guinness World Records, Sigui : "Longest religious ceremony."[1] (retrieved March 13, 2020)

Bibliography

[edit]- Aune, David E. (2003). "Cosmology". Westminster Dictionary of the New Testament and Early Christian Literature. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

- Bernstein, Alan E. (1996). The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian Worlds. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8131-7.

- Berlin, Adele (2011). "Cosmology and creation". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973004-9.

- Lee, Sang Meyng (2010). The Cosmic Drama of Salvation. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-150316-0.

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534849-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Religious cosmologies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Religious cosmologies at Wikimedia Commons