1970 Ancash earthquake

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

| |

| UTC time | 1970-05-31 20:23:29 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 796163 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 31 May 1970 |

| Local time | 15:23:29 |

| Duration | ~ 45 seconds[1][2] |

| Magnitude | 7.9 Mw[3][4] |

| Depth | 45 km (28 mi)[3] |

| Epicenter | 9°24′S 78°54′W / 9.4°S 78.9°W[4] |

| Type | Normal |

| Areas affected | Peru |

| Max. intensity | MMI VIII (Severe)[1] |

| Peak acceleration | 0.1 g at Lima[2] |

| Tsunami | .38 m (1 ft 3 in)[5] |

| Casualties | 66,794–70,000 dead[5] 50,000 injured[5] |

The 1970 Ancash earthquake (also known as the Great Peruvian earthquake) occurred on 31 May off the coast of Peru in the Pacific Ocean at 15:23:29 local time. Combined with a resultant landslide, it is the most catastrophic natural disaster in the history of Peru. Due to the large amounts of snow and ice included in the landslide that caused an estimated 66,000-70,000 casualties, it is also considered to be the world's deadliest avalanche.

Earthquake

[edit]

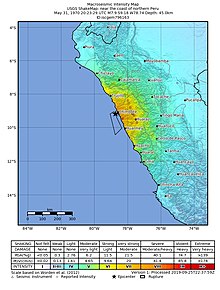

The undersea earthquake struck on a Sunday afternoon and lasted about 45 seconds. The shock affected the Peruvian regions of Ancash and La Libertad. The epicenter was located 35 km (22 mi) off the coast of Casma and Chimbote in the Pacific Ocean, where the Nazca plate is being subducted beneath the South American plate. It had a moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe). The focal mechanism and hypocentral depth of the earthquake show that the earthquake was a result of normal faulting within the subducting slab.[6]

Damage

[edit]The earthquake affected an area of about 83,000 km2, an area larger than Belgium and the Netherlands combined, in the north-central coast and the Sierra (highlands) of the Ancash Region and southern La Libertad Region. Reports of damage and casualties came from Tumbes to Pisco and Iquitos in the east. Damage and panic scenes were reported in some parts of Ecuador. Tremors were also felt in western and central Brazil.

It was a system-wide disaster, affecting such a widespread area that the regional infrastructure of communications, commerce, and transportation was destroyed. Economic losses surpassed half a billion US dollars. Cities, towns, villages—and homes, industries, public buildings, schools, electrical generation and distribution systems, water, sanitary and communications facilities—were seriously damaged or were destroyed.

The coastal towns and cities of Chimbote (the largest city in Ancash), Casma, Supe and Huarmey were hit hard; but the Andean valley known as the Callejón de Huaylas suffered the most intense and sweeping damage, with the regional capital, Huaraz, and Caraz and Aija being partially destroyed. Trujillo, the country's third-largest city, and Huarmey suffered minor damage.

In Chimbote, Carhuaz and Recuay, between 80% and 90% buildings were destroyed, affecting about three million people.

The Pan-American highway was also damaged, which made the arrival of humanitarian aid difficult. The Cañón del Pato hydroelectricity generator was damaged by the Santa River and the railway connecting Chimbote with the Santa Valley was left unusable on 60% of its route.

The Peruvian government has forbidden excavation in the area where the town of Yungay is buried, declaring it a national cemetery. The children who survived in the local stadium were resettled around the world. In 2000, the tragedy inspired the government to declare 31 May as Natural Disaster Education and Reflection Day, during which many schools practice an earthquake drill to commemorate the disaster.

Landslide

[edit]The northern wall of Mount Huascarán was destabilized, causing a rock, ice and snow avalanche and burying the towns of Yungay and Ranrahirca. The avalanche started as a sliding mass of glacial ice and rock about 910 metres (2,990 ft) wide and 1.6 km (1 mile) long. It advanced about 18 kilometres (11 mi) to the village of Yungay at an average speed of 280 to 335 km per hour.[7] The fast-moving mass picked up glacial deposits and by the time it reached Yungay, it is estimated to have consisted of about 80 million m3 of water, mud, rocks and snow.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Plafker, Ericksen & Fernández Concha 1971, p. 545

- ^ a b Cluff, L.S. (1971), "Peru earthquake of May 31, 1970; Engineering geology observations" (PDF), Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 61 (3): 514, Bibcode:1971BuSSA..61..511C, doi:10.1785/BSSA0610030511, S2CID 132218116

- ^ a b ISC (2014), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009), Version 1.05, International Seismological Centre

- ^ a b Utsu, T. R. (2002), "A List of Deadly Earthquakes in the World: 1500–2000", International Handbook of Earthquake & Engineering Seismology, Part A, Volume 81A (First ed.), Academic Press, p. 708, ISBN 978-0124406520

- ^ a b c PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, September 4, 2009

- ^ Dewey, J.W.; Spence, W. (1979). Wyss, M. (ed.). "Seismic gaps and source zones of recent large earthquakes in coastal Peru". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 117 (6): 1148–1171. Bibcode:1979PApGe.117.1148D. doi:10.1007/BF00876212. S2CID 140643448.

- ^ Plafker, Ericksen & Fernández Concha 1971, p. 543

Sources

- Plafker, G.; Ericksen, G.E.; Fernández Concha, J. (1971), "Geological aspects of the May 31, 1970, Perú earthquake" (PDF), Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 61 (3): 543–578, Bibcode:1971BuSSA..61..543P, doi:10.1785/BSSA0610030543, S2CID 130140366

External links

[edit]- IRIS SeismoArchive for 1970 Peru earthquake – IRIS Consortium

- Yungay 1970–2009: remembering the tragedy of The Earthquake – Peruvian Times

- "In pictures: Peru's most catastrophic natural disaster" BBC News website (accessed and dated 31 May 2020)

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- Documentary Footage by Texan Relief Workers in Peru, Ancash Earthquake of 1970 on Texas Archive of the Moving Image