Gunpowder weapons in the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty continued to improve on gunpowder weapons from the Yuan and Song dynasties. During the early Ming period larger and more cannons were used in warfare. In the early 16th century Turkish and Portuguese breech-loading swivel guns and matchlock firearms were incorporated into the Ming arsenal. In the 17th century Dutch culverin were incorporated as well and became known as hongyipao.[1][2] At the very end of the Ming dynasty, around 1642, Chinese combined European cannon designs with indigenous casting methods to create composite metal cannons that exemplified the best attributes of both iron and bronze cannons.[1][3][4] While firearms never completely displaced the bow and arrow, by the end of the 16th century more firearms than bows were being ordered for production by the government, and no crossbows were mentioned at all.[5][6]

Early Ming period

Number of gunners

The Ming dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang, who declared his reign to be the era of Hongwu, or "Great Martiality," made prolific use of gunpowder weapons for his time. Early Ming military codes stipulated that ideally 10 percent of all soldiers should be gunners. By 1380, twelve years after the Ming dynasty's founding, the Ming army boasted around 130,000 gunners out of its 1.3 to 1.8 million strong army. Under Zhu Yuanzhang's successors, the percentage of gunners climbed higher and by the 1440s it reached 20 percent. In 1466 the ideal composition was 30 percent.[7]

Ammunition

Gunpowder corning had been developed by 1370 to increase the explosive power of land mines.[8] It's argued that corned gunpowder may have been used for guns as well according to one record of a fire-tube shooting a projectile 457 meters, which was probably only possible at the time with the usage of corned powder.[9] Around the same time Ming guns transitioned from stone shots to iron ammunition, which has greater density than stone.[10] They also made use of shells since at least 1412.[11]

Guns

The Hongwu Emperor created a Bureau of Armaments (軍器局) which was tasked with producing every three years 3,000 handheld bronze guns, 3,000 signal cannons, and ammunition as well as accoutrements such as ramrods. His Armory Bureau (兵仗局) was responsible for producing types of guns known as "great generals," "secondary generals," "tertiary generals," and "gate-seizing generals." Other firearms such as "miraculous [fire] lances," "miraculous guns," and "horse-beheading guns" were also produced. It is unclear what proportion or how many of each type were actually manufactured.[12]

Most early Ming guns weighed only two to three kilograms while guns considered "large" at the time weighed around only 75 kilograms. During Siege of Suzhou in 1366 the Ming army fielded "large" cannons weighing up to 80 kilograms, which were about a meter in length, and had a muzzle diameter of about 21 centimeters.[13] A gun known as the "Great Bowl-Mouth Tube" (大碗口筒) dated to 1372 weighs only 15.75 kilograms and was 36.5 centimeters long, its muzzle 11 centimeters in diameter. Other excavated guns of this type range from 8.35 to 26.5 kilograms. They were usually mounted on ships or gates as defensive weapons. Accuracy was low and they were limited to a range of only 50 paces or so.[14]

In China cannons had played a significant role in siege battles since the mid 14th century. For example in 1358 during the Siege of Shaoxing the Ming army attacked the city and the defenders "used ... fire tubes to attack the enemy's advance guard".[13] The siege was won by the defenders, whose "fire tubes went off all at once, and the [attacker's] great army could not stand against them and had to withdraw."[15] In 1363 Chen Youliang failed to take Nanchang due to the defenders' use of cannons and was forced to set up a blockade in an attempt to starve them out.[16] Cannons were also used on the frontier as garrison artillery from 1412 onwards.[17]

Cannons were less useful for the besieging army. In the Siege of Suzhou of 1366, the Ming army fielded 2,400 large and small cannons in addition to 480 trebuchets, but neither were able to breach the city walls despite "the noise of the guns and the paos went day and night and didn't stop."[18] Chinese city walls tend to be much thicker than other parts of the world, and Suzhou was no different. Contemporary documents show that the wall had a width of 11 meters at the base, a height of 7 meters, and a length of 17 kilometers all around.[13] The city defenses were eventually overcome through a breach in the gates made by traditional manual mining and battering. This was only possible because the defenders were already starving by mid-autumn of 1367 and unable to put up a proper resistance, succumbing to the onslaught of a frontal assault.[19]

In 1388 cannons were used against war elephants successfully during the Ming–Mong Mao War and again in 1421 during the Lam Sơn uprising.[20][21] In 1414 the Ming army clashed with an Oirat force near the Tula River and frightened them so much with their guns that the Oirats fled without their spare horses, only to be ambushed by concealed Chinese guns. According to a Chinese observer the Oirats avoided battle several days later, "fearing that the guns had arrived again."[22]

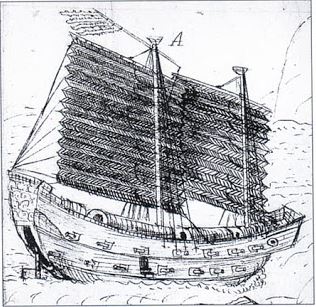

Cannons were less decisive in naval battles. In the Battle of Lake Poyang on 29 August 1363 Zhu Yuanzhang's fleet arrived armed with "fire bombs, fire guns, fire arrows, fire seeds [probably grenades], large and small fire lances, large and small 'commander' fire-tubes, large and small iron bombs, rockets."[23] His fleet engaged Chen's under orders to "get close to the enemy's ships and first set off gunpowder weapons (發火器), then bows and crossbows, and finally attack their ships with short range weapons."[24] However it was fire bombs hurled using ship mounted trebuchets that succeeded in "burning twenty or more enemy vessels and killing or drowning many enemy troops."[25] Zhu eventually came out victorious by ramming and burning the enemy fleet with fire ships. While guns were used during the battle, ultimately they were not pivotal to success, and the battle was won using incendiary weapons.[26]

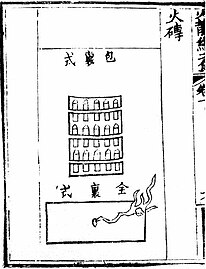

Early Ming cannons coalesced into a few typical designs. There was the crouching tiger cannon, a small cannon fitted with a metal collar and two legs for support.[17] There was a middling cannon known as the "awe-inspiring long range cannon" which added a sight and weighed around 85 kilograms.[27] Larger cannons such as the great general and great divine cannons were also developed and at least 300 of them were being made in 1465.[17] The muzzle loading wrought iron "great general cannon" (大將軍炮) weighed up to 360 kilograms and could fire a 4.8 kilogram lead ball. Its heavier variant, the "great divine cannon" (大神銃), could weigh up to 600 kilograms and was capable of firing several iron balls and upward of a hundred iron shots at once. These were the last indigenous Chinese cannon designs prior to the incorporation of European models in the 16th century.[28]

-

A depiction of the "crouching tiger cannon" from the Huolongjing

-

Two "awe-inspiring long range cannons" (威遠砲), from the Huolongjing.

-

A 'seven star cannon' (qi xing chong) from the Huolongjing. It was a seven barreled organ gun with two auxiliary guns by its side on a two-wheeled carriage.

-

An illustration of a bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" from the Huolongjing.

-

Drawing of a "great general cannon", from Wubei Yaolue.

-

A "barbarian attacking cannon" as depicted in the Huolongjing. Chains are attached to the cannon to adjust recoil.

-

A "great divine cannon" from the Dengtan Bijiu.

Stagnation theories

While China was the birthplace of gunpowder the guns there remained relatively small and light, weighing less than 80 kilograms or less for the large ones, and only a couple kilograms at most for the small ones during the early Ming era. Guns themselves had proliferated throughout China and become a common sight during sieges, so the question has arisen then why larger wall breaking guns were not first developed in China.

Nomad theory

Asianist Kenneth Chase argues that gun development stagnated during the Ming dynasty due to the type of enemy faced by the Chinese: horse nomads. Chase argues that guns were not particularly useful against these opponents.[29] Guns were supposedly problematic to deploy against nomads because of their size and slow speed, drawing out supply chains, and creating logistical challenges. Theoretically, the more mobile nomads took the initiative in sallying, retreating, and engaging at will. Chinese armies therefore relied less heavily on guns in warfare than Europeans, who fought large infantry battles and sieges which favored guns, or so Chase argues.

However, the Chase hypothesis has been criticized by Tonio Andrade.[29] According to Andrade, the Chinese themselves considered guns to be highly valuable against nomads. During the Ming-Mongol wars of the 1300s and early 1400s, guns were utilized, notably in defending against a Mongol invasion in 1449, and guns were in high demand along the northern borders where gun emplacements were common.[29] Several sources make it clear that Chinese military leaders found guns to be highly effective against nomads throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. The military scholar Weng Wanda goes as far as to claim that only with firearms could one hope to succeed against the fast moving Mongols, and purchased special guns for both the Great Wall defenses and offensive troops who fought in the steppes. Andrade also points out that Chase downplays the amount of warfare going on outside of the northern frontier, specifically southern China where huge infantry battles and sieges such as in Europe were the norm. In 1368 the Ming army invaded Sichuan, Mongolia, and Yunnan. Although little mention of firearm is used in accounts of the Mongolia campaign, Ming cannons readily routed the war elephants of Yunnan,[30] and in the case of Sichuan, both sides employed equally potent firearms. When the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang died, the civil war which ensued had Chinese armies fighting one another, again with equally powerful firearms. After the usurper Yongle's victory, the Ming embarked upon yet another five expeditions into Mongolia alongside an invasion of Dai Viet, many of their troops wielding firearms. In 1414 the Ming army clashed with an Oirat force near the Tula River and frightened them so much with their guns that the Oirats fled without their spare horses, only to be ambushed by concealed Chinese guns. According to a Chinese observer the Oirats avoided battle several days later, "fearing that the guns had arrived again."[22] In Vietnam, as with Yunnan, the war elephants fared poorly and were defeated with a combination of arrows and firearms. Chinese firearms were used in defensive fortifications to some effect, but were ineffective at targeting individual targets such as Vietnamese guerillas presented themselves.[21]

Economic theory

The nomad theory has also been criticized by Stephen Morillo for its reliance on a simple cause and effect analysis.[31] Alternatively Morillo suggests that the major difference between Chinese and European weapon development was economic. Within Morillo's framework, European weapons were more competitive due to private manufacturing whereas Chinese weapons were manufactured according to government specifications. Although generally true, Peter Lorge points out that gun specifications were widespread in China, and ironically the true gun was first developed during the Song dynasty, when guns were the exclusive enterprise of the government, suggesting that the economics of production were less influential on gun development than assumed. In contrast, less innovation occurred during the Ming dynasty when most of production was shifted to the domain of private artisans.[31] Andrade concludes that although the Chase hypothesis of nomad caused stagnation should not be discarded outright, it does not offer a full explanation for the stagnation of firearm development in China.[32]

Chinese wall theory

According to Tonio Andrade, Chinese firearm development was not hindered by metallurgy, which was sophisticated in China, and the Ming dynasty did construct large guns in the 1370s, but never followed up afterwards. Nor was it the lack of warfare, which other historians have suggested to be the case, but does not stand up to scrutiny as walls were a constant factor of war which stood in the way of many Chinese armies since time immemorial into the twentieth century. The answer Andrade provides is simply that Chinese walls were much less vulnerable to bombardment.[33] Andrade argues that traditional Chinese walls were built differently from medieval European walls in ways which made them more resistant to cannon fire.

Chinese walls were bigger than medieval European walls. In the mid-twentieth century a European expert in fortification commented on their immensity: "in China … the principal towns are surrounded to the present day by walls so substantial, lofty, and formidable that the medieval fortifications of Europe are puny in comparison."[33] Chinese walls were thick. Ming prefectural and provincial capital walls were ten to twenty meters thick at the base and five to ten meters at the top.

In Europe the height of wall construction was reached under the Roman Empire, whose walls often reached ten meters in height, the same as many Chinese city walls, but were only 1.5 to 2.5 meters thick. Rome's Servian Walls reached 3.6 and 4 meters in thickness and 6 to 10 meters in height. Other fortifications also reached these specifications across the empire, but all these paled in comparison to contemporary Chinese walls, which could reach a thickness of 20 meters at the base in extreme cases. Even the walls of Constantinople which have been described as "the most famous and complicated system of defence in the civilized world,"[34] could not match up to a major Chinese city wall.[35] Had both the outer and inner walls of Constantinople been combined, they would have only reached roughly a bit more than a third the width of a major wall in China.[35] According to Philo the width of a wall had to be 4.5 meters thick to be able to withstand artillery.[36] European walls of the 1200s and 1300s could reach the Roman equivalents but rarely exceeded them in length, width, and height, remaining around two meters thick. It is apt to note that when referring to a very thick wall in medieval Europe, what is usually meant is a wall of 2.5 meters in width, which would have been considered thin in a Chinese context.[37] There are some exceptions such as the Hillfort of Otzenhausen, a Celtic ringfort with a thickness of forty meters in some parts, but Celtic fort-building practices died out in the early medieval period.[38] Andrade goes on to note that the walls of the marketplace of Chang'an were thicker than the walls of major European capitals.[37]

Aside from their immense size, Chinese walls were also structurally different from the ones built in medieval Europe. Whereas European walls were mostly constructed of stone interspersed with gravel or rubble filling and bonded by limestone mortar, Chinese walls had tamped earthen cores which absorbed the energy of artillery shots.[39] Walls were constructed using wooden frameworks which were filled with layers of earth tamped down to a highly compact state, and once that was completed the frameworks were removed for use in the next wall section. Starting from the Song dynasty these walls were improved with an outer layer of bricks or stone to prevent corrosion, and during the Ming, earthworks were interspersed with stone and rubble.[39] Most Chinese walls were also sloped, which better deflected projectile energy, rather than vertical.[40]

The Chinese Wall Theory essentially rests on a cost benefit hypothesis, where the Ming recognized the highly resistant nature of their walls to structural damage, and could not imagine any affordable development of the guns available to them at the time to be capable of breaching said walls. Even as late as the 1490s a Florentine diplomat considered the French claim that "their artillery is capable of creating a breach in a wall of eight feet in thickness"[41] to be ridiculous and the French "braggarts by nature."[41] In fact twentieth century explosive shells had some difficulty creating a breach in tamped earthen walls.[42]

We fought our way to Nanking and joined in the attack on the enemy capital in December. It was our unit which stormed the Chunghua Gate. We attacked continuously for about a week, battering the brick and earth walls with artillery, but they never collapsed. The night of December 11, men in my unit breached the wall. The morning came with most of our unit still behind us, but we were beyond the wall. Behind the gate great heaps of sandbags were piled up. We 'cleared them away, removed the lock, and opened the gates, with a great creaking noise. We'd done it! We'd opened the fortress! All the enemy ran away, so we didn't take any fire. The residents too were gone. When we passed beyond the fortress wall we thought we had occupied this city.[43]

— Nohara Teishin

Andrade goes on to question whether or not Europeans would have developed large artillery pieces in the first place had they faced the more formidable Chinese style walls, coming to the conclusion that such exorbitant investments in weapons unable to serve their primary purpose would not have been ideal.[44]

Middle Ming period

Folangji

The middle Ming period saw the arrival of European guns in China. As early as 1518 Portuguese breech-loading swivel gun known as folangji could be purchased in the Ming dynasty.[45] In 1523 a test batch of 32 were produced for the court and in 1528 4,000 were produced for border fortifications.[46] Views diverge on whether the origin of the cannon is Portuguese or Turkish. There was a confusion whether folangji was supposed to be the name of a people (the Portuguese) or name of a weapon. In fact the word folangji represent 2 different words with different etymology. The term folangji as a weapon is related to the prangi carried in Ottoman galleys and farangi used by Babur. The word folangji as an ethnonim (Frankish or Portuguese) is unrelated.[47]: 143 The Ottoman prangi guns may have reached Indian ocean before either Ottoman or Portuguese ships did.[47]: 242 In the History of the reign of Wan Li (萬厲野獲編), by Shen Defu, it is said that "After the reign of Hong Zhi (1445-1505), China started having Fu-Lang-Ji cannons, the country of which was called in the old times Sam Fu Qi". In volume 30 about "The Red-Haired Foreigners" he wrote "After the reign of Zhengtong (1436-1449) China got hold of Fu-Lang-Ji cannons, the most important magic instrument of foreign people". He mentioned the cannons some 60 or 70 years prior to the first reference about Portuguese. It was impossible for the Chinese to get hold of the Portuguese cannons prior to their arrival.[48] Pelliot viewed that the folangji gun reached China before Portuguese did.[49] Needham noted that breech-loading guns were already familiar in Southern China in 1510, as a rebellion in Huang Kuan was destroyed by more than 100 folangji.[50]: 372

Fa Gong

The Fa Gong was a super heavy artillery piece that entered the Ming arsenal in the mid 16th century. Probably derived from falconets of European design, the Fa Gong was a bronze muzzle loading cannon that could weigh from 630 to 3,000 kilograms. The largest ones however were only used for coastal defense.[51] Both the Jixiao xinshu and Chouhai tubian record the Fa Gong as a cannon that ships should carry, with the caveat that improper use risked damage to one's own ship. However, accompanying illustrations typically depict soldiers with hand-held weapons only; the illustrations show no cannon onboard ships.[52]

Matchlocks

Arquebuses may have been introduced to China in 1523,[53] and by 1548, arquebuses were being used in small numbers by Ming forces. They were primarily used against wokou pirates and their success led to the manufacture of more matchlocks. Thousands of matchlock firearms were being ordered for production a few years later. For example, in 1558, the Central Military Weapon Bureau gave an order for the production of 10,000 matchlocks.[54]

In 1560, Qi Jiguang, who was originally ambivalent towards matchlocks but turned to it after suffering defeats at the hands of the wokou, described the matchlock in the following fashion:

It is unlike any other of the many types of fire weapons. In strength it can pierce armor. In accuracy it can strike the center of targets, even to the point of hitting the eye of a coin [i.e., shooting right through a coin], and not just for exceptional shooters.… The arquebus [鳥銃] is such a powerful weapon and is so accurate that even bow and arrow cannot match it, and … nothing is so strong as to be able to defend against it.[55]

— Jixiao Xinshu

In Zhao Shizhen's book of 1598 AD, the Shenqipu, there were illustrations of Ottoman Turkish musketmen with detailed illustrations of their muskets, alongside European musketeers with detailed illustrations of their muskets.[56] There was also illustration and description of how the Chinese had adopted the Ottoman kneeling position in firing while using European-made muskets,[57] though Zhao Shizhen described the Turkish muskets as being superior to the European muskets.[58] The Wubei Zhi (1621) later described Turkish muskets that used a rack-and-pinion mechanism, which was not known to have been used in any European or Chinese firearms at the time.[59]

Volley fire

Qi Jiguang applied the concept of volley fire to matchlock firearms and deployed teams of 10 musketeers. The optimal musketry formation that Qi proposed was a 12 man musket team similar to the melee mandarin duck formation. However, instead of fighting in a hand to hand formation, they operated on the principle of volley fire, which Qi pioneered prior to the publication of the first edition of the Jixiao Xinshu.[55] The teams could be arranged in a single line, two layers deep with five musketeers each, or five layers deep with two muskets per layer. Once the enemy was within range, each layer would fire in succession, and afterwards a unit armed with traditional close combat weapons would move forward ahead of the musketeers. The troops would then enter into melee combat with the enemy together. Alternatively, the musketeers could be placed behind wooden stockades or other fortifications, firing and reloading continuously by turns.[60]

In 1571 Qi prescribed an ideal infantry regiment of 1,080 musketeers out of 2,700 men, or 40 percent of the infantry force. However it is not known how well this was actually implemented, and there is evidence that Qi was met with stiff resistance to the incorporation of newer gunpowder weapons in northern China while he was stationed there.[61] He writes that "in the north soldiers are stupid and impatient, to the point that they cannot see the strength of the musket, and they insist on holding tight to their fast lances (a type of fire lance), and although when comparing and vying on the practice field the musket can hit the bullseye ten times better than the fast-lance and five times better than the bow and arrow, they refuse to be convinced."[61]

The musket was originally considered a powerful weapon, and in attacking the enemy is one that has been much relied upon. But how is it that so many officers and soldiers don't think it can be relied upon heavily? The answer lies in the fact that in drills and on the battlefield, when all the men fire at once, the smoke and fire settle over the field like miasmal clouds, and not a single eye can see, and not a single hand can signal. Not all [soldiers] hold their guns level, or they don't hold them to the side of their cheek, or they don't use the sights, or they let their hands droop and support it to hold it up, and one hand holds the gun and one hand uses the fuse to touch off the fire, thus failing to use the matchlock grip— what of them? It's just a case of being out of practice and uncourageous, hurrying but not being able to take out the fire fuse and place it in the matchlock grip, trying for speed and convenience. In this way, there is absolutely no way to be accurate, and so how could one value muskets? Especially given that the name of the weapon is "bird-gun," which comes from the way that it can hit a flying bird, hitting accurately many times. But in this way, fighting forth, the power doesn't go the way one intends, and one doesn't know which way it goes— so how can one hit the enemy, to say nothing of being able to hit a bird?[62]

-

A Ming matchlock firearm from the Shenqipu, 1598.

-

A Ming matchlock from the Wubei Zhi, 1628.

-

Illustration of a 1639 Ming musketry volley formation.

-

The Fa Gong, a super heavy muzzle loading bronze cannon that could weigh from 630 to 3,000 kilograms, from the Chouhai Tubian, 1565.

-

A typical folangji swivel gun from the Lianbing Zaji, 1571.

-

The "invincible divine flying cannon" is a breech loading naval gun. From the Jixiao Xinshu, 1584.

Late Ming period

Some early Ming cannon designs continued to see service well into the late Ming era. For example the crouching tiger cannon was still being used during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98).[17]

Lord Ye's divine gun

In the latter half of the 16th century Ye Mengxiong developed a breech loading cannon with a range of 800 paces known as "Lord Ye's divine gun". This new variant lengthened the chamber to around two meters and weighed around 150 kilograms.[17][63]

In 1592 it made up a part of the Ming artillery train during a campaign against a Mongol rebellion in Ningxia.[17]

Breech loading matchlock

Zhao Shizhen developed breech loading matchlocks in the late 16th century. These used pre-loaded tube shaped chambers that could be loaded into the breech of the gun barrel. Gas leaking limited the effectiveness of these weapons and could even pose a danger to the user due to the close proximity of the matchlock mechanism. To prevent gas leaks Zhao designed interchangeable gun barrels, but these were very long and unwieldy.[64]

Rain cover

Zhao Shizhen also developed a rain cover for the matchlock. The bronze rain cover was connected to a weighted pendulum that always pointed downwards even if the gun's orientation changed. This addition was cost prohibitive and could not be produced in large amounts.[65]

Bayonet

In the early 17th century He Rubin added a plug bayonet to the breech loading matchlock.[66]

-

A matchlock with a rain cover from the Shenqipu, 1598.

-

A man loading a matchlock with a rain cover.

-

A breech loading matchlock from the Shenqipu, 1598.

-

A breech loading matchlock with interchangeable barrels from the Shenqipu, 1598.

-

A barrel holder which doubles as a shield from the Shenqipu, 1598.

-

A breech loading matchlock with a plug bayonet from the Binglu, 1606.

Hongyipao

Chinese began producing hongyipao, "red barbarian cannons", in 1620. These were European style muzzle-loading culverins.[67] The hongyipao played a pivotal role in the Ming defense against the Jurchens at the Battle of Ningyuan, but the technological advantage didn't last long. Kong Youde defected to the Later Jin (1616–1636) in 1631, taking with him knowledge of the hongyipao.[1]

Flintlocks

Around 1635 the Chinese acquired flintlock firearms or at least had some detailed knowledge of their existence. The new mechanism didn't catch on however and the Chinese never incorporated it into their arsenal.[68]

Composite metal cannons

Chinese gunsmiths continued to modify "red barbarian" cannons after they entered the Ming arsenal, and eventually improved upon them by applying native casting techniques to their design. In 1642 Ming foundries merged their own casting technology with European cannon designs to create a distinctive cannon known as the "Dingliao grand general." Through combining the advanced cast-iron technique of southern China and the iron-bronze composite barrels invented in northern China, the Dingliao grand general cannons exemplified the best of both iron and bronze cannon designs. Unlike traditional iron and bronze cannons, the Dingliao grand general'rs inner barrel was made of iron, while the exterior of brass.[1][4] Scholar Huang Yi-long describes the process:

They ingeniously took advantage of the fact that the melting temperature of copper (which is around 1000C) was lower than the casting temperature of iron (1150 to 1200C), so that just a bit after the iron core had cooled, they could then, using a clay or wax casting mold, add molten bronze to the iron core. In this way, the shrinkage that attended the cooling of the external brass would [reinforce the iron, which would] enable the tube to be able to resist intense firing pressure.[1]

The resulting bronze-iron composite cannons were superior to iron or bronze cannons in many respects. They were lighter, stronger, longer lasting, and able to withstand more intensive explosive pressure. Chinese artisans also experimented with other variants such as cannons featuring wrought iron cores with cast iron exteriors. While inferior to their bronze-iron counterparts, these were considerably cheaper and more durable than standard iron cannons. Both types met with success and were considered "among the best in the world"[69] during the 17th century.

Soon after the Ming started producing the composite metal Dingliao grand generals in 1642, Beijing was captured by the Manchu Qing dynasty and along with it all of northern China. The Manchu elite did not concern themselves directly with guns and their production, preferring instead to delegate the task to Chinese craftsmen, who produced for the Qing a similar composite metal cannon known as the "Shenwei grand general." However, after the Qing gained hegemony over East Asia in the mid-1700s, the practice of casting composite metal cannons fell into disuse until the dynasty faced external threats once again in the Opium War of 1840, at which point smoothbore cannons were already starting to become obsolete as a result of rifled barrels.[4]

The concept of composite metal cannons is not exclusive to China. Although the southern Chinese started making cannons with iron cores and bronze outer shells as early as the 1530s, they were followed soon after by the Gujarats, who experimented with it in 1545, the English at least by 1580, and Hollanders in 1629. However the effort required to produce these weapons prevented them from mass production.The Europeans essentially treated them as experimental products, resulting in very few surviving pieces today.[70][71] Of the currently known extant composite metal cannons, there are 2 English, 2 Dutch, 12 Gujarati, and 48 from the Ming-Qing period.[4]

Bastion fort

In 1632, Sun Yuanhua advocated for the construction of angled bastion forts in his Xifashenji so that their cannons could better support each other. The officials Han Yun and Han Lin noted that cannons on square forts could not support each side as well as bastion forts. Their efforts to construct bastion forts and their results were inconclusive. Ma Weicheng built two bastion forts in his home county, which helped fend off a Qing incursion in 1638. By 1641, there were ten bastion forts in the county. Before bastion forts could be spread any further, the Ming dynasty fell in 1644, and they were largely forgotten as the Qing dynasty was on the offensive most of the time and had no use for them.[72]

Other gunpowder weapons

Rockets

The basic rocket weapon, otherwise known as the fire arrow in Chinese, was a tube of gunpowder and a fuse attached to an arrow. Variants of the basic variety included:

- "Sail-nailing arrow", a naval weapon used to set fire to the sails of enemy ships. It included a poisonous smoke and barbed arrowhead to prevent enemies from putting out the fire.[73]

- "Flying saber, spear, sword, and swallowtail arrows", which had specialized arrowheads and larger rocket tubes to punch through armour.[74]

Rocket launchers

Rocket launchers included:

- "Fire basket", a handheld bamboo basket holding 20 fire arrows.[75]

- "Long serpent enemy breaker", a handheld rocket pod with 32 fire arrows.[76]

- "Convocation of eagles chasing hare", a double ended handheld rocket pod containing 30 fire arrows on each side for a total of 60 fire arrows.[77]

- "Nest of bees", a hexagonal, wagon mounted, 32 shot fire arrow launcher.[78]

- "Charging leopard pack", an octagonal rocket pod carrying 40 fire arrows.[79]

- "Hundred tiger rush", a box shaped rocket launcher carrying 100 fire arrows.[80]

- "Divine fire arrow screen", a stationary rocket launcher with a pressure plate trigger. It carries 100 fire arrows.[81]

-

An illustration of fire arrow launchers as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. The launcher is constructed using basketry.

-

A "long serpent enemy breaking" fire arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. It carries 32 medium small poisoned rockets and comes with a sling to carry on the back.

-

The 'convocation of eagles chasing hare' rocket launcher from the Wubei Zhi. A double-ended rocket pod that carries 30 small poisoned rockets on each end for a total of 60 rockets. It carries a sling for transport.

-

A "nest of bees" (yi wo feng 一窩蜂) arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. So called because of its hexagonal honeycomb shape.

-

A "charging leopard pack" arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi.

-

The 'divine fire arrow screen' from the Huolongjing. A stationary arrow launcher that carries one hundred fire arrows.

Rocket carts

- "Fire arrow cart", a rocket cart with no specifications given.

- "Wheelbarrow fire engine", a rocket cart constructed by joining together four 'long serpent' rocket launchers, two square 'hundred tigers' rocket-arrow launchers, two multiple-bullet emitters, and two spears for close quarter combat.

- "Assault-barrow rocket launcher", multiple assault-barrow rocket-launchers side by side.

- "Modified martial steel cart", two connected wheelbarrows, each equipped with two small cannons, 27 rockets, and a shield.

- "Hidden barbarian charging wheel cart", a wheelbarrow equipped with 40 rockets, eight spears, and two shields.

Bombs

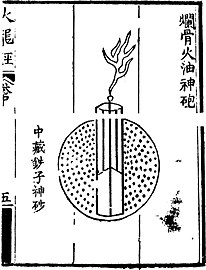

The Huolongjing describes several different types of bombs. The "divine bone dissolving fire oil bomb" was made of a cast iron casing filled with tung oil, sal ammoniac, feces, scallion juice, and iron pellets or porcelain shards. Another was called the "magic fire meteor going against the wind bomb", which was made using a wooden core filled with blinding gunpowder. It's not certain what the point of the wooden core was, but the bomb could be made very small or so large that it needed to be transported by animals. A type of weak casing bomb called the "bee swarm bomb" was made using bamboo and paper for the case, and filled with gunpowder and iron caltrops. The explosion was fairly weak and it was intended for setting the sails of ships on fire or causing havoc in enemy camps. Cases could also be made of wood for bombs such as the "match for ten thousand enemies", which was given a double wooden casing so that it did not explode, but rather spun around emitting fire.[82]

-

A 'watermelon bomb' (xi gua pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. It contains 'fire rats,' mini rockets with hooks.

-

A 'fire brick' (huo zhuan) as depicted in the Huolongjing. It contains mini-rockets bearing sharp little spikes.

-

Depiction of a' wind-and-dust bomb' (feng chen pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

An illustration of a fragmentation bomb known as the 'divine bone dissolving fire oil bomb' (lan gu huo you shen pao) from the Huolongjing. The black dots represent iron pellets.

-

A 'rumbling thunder bomb' (hong lei pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. The text describes ingredients including mini-rockets and caltrops with poisons.

-

'Dropping from heaven' (tian zhui pao) bombs as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

'Bee swarm bombs' (qun feng pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Paper casing filled with gunpowder and shrapnel.

-

A 'divine fire meteor which goes against the wind' (zuan feng shen huo liu xing pao) bomb as depicted in the Huolongjing.

-

A 'flying-sand divine bomb releasing ten thousand fires' (wan huo fei sha shen pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. A weak casing device possibly used in naval combat.

Mines

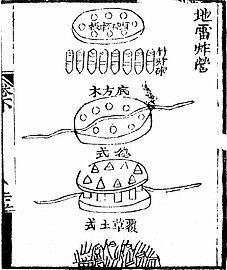

Land mines may have been used since the Song dynasty in 1277 against the Mongols, however they were not described in detail until the Huolongjing was written in the latter half of the 14th century. The Huolongjing describes several types of mines, one of which was called the "invincible ground thunder mine" which was made of cast iron and buried where the enemies were expected to arrive. The trigger mechanism is not described, only that the mines were exploded at a given signal. The "ground thunder explosive camp" was a large group of mines made of bamboo tubes filled with oil, gunpowder, and lead or iron pellets. The fuse was attached to the bottom of the tube which was ignited when disturbed. The "self tripped trespass land mine" operated in a similar fashion, except the container was made of iron, rock, porcelain or earthenware. The fuses were connected together through a series of fire ducts so that they all exploded at once. A "stone cut explosive land mine" was used for defending cities. Its fuse was slotted through a section of bamboo.[83]

The Binglu describes a type of mine called the "supreme pole combination mine" which mounted a battery of little guns which set off automatically, although the trigger mechanism is not described. According to the Huolongjing, the explosive mine was set off using a steel whee mechanism:

The explosive mine is made of cast iron about the size of a rice-bowl, hollow inside with (black) powder rammed into it. A small bamboo tube is inserted and through this passes the fuse, while outside (the mine) a long fuse is led through fire-ducts. Pick a place where the enemy will have to pass through, dig pits and bury several dozen such mines in the ground. All the mines are connected by fuses through the gunpowder fire-ducts, and all originate from a steel wheel (gang lun). This must be well concealed from the enemy. On triggering the firing device the mines will explode, sending pieces of iron flying in all directions and shooting up flames towards the sky.[84]

However the "steel wheel" mechanism was not described in detail until the Binglu was published in 1606. It consisted of two steel wheels placed on flints with a cord and weight attached to them. The weight was held in place by a pin, which when removed by stepping on a plate attached to it, would release the weight, causing the wheels to produce sparks by rubbing against the flints, and thus setting off the fuse. The Wubei Zhi also describes a trigger using slow burning incandescent material. The incandescent material was made of sandal-wood powder, iron rust, 'white' charcoal powder, willow charcoal powder, and dried powdered flesh of red dates. This was used for the "underground sky soaring thunder", which consisted of mines attached to a bowl of weapons above ground. When enemies pulled on the weapons, the mines would explode.[85]

For naval mines, the Huolongjing describes the use of slowly burning joss sticks that were disguised and timed to explode against enemy ships nearby:

The sea–mine called the 'submarine dragon–king' is made of wrought iron, and carried on a (submerged) wooden board, [appropriately weighted with stones]. The (mine) is enclosed in an ox-bladder. Its subtlety lies in the fact that a thin incense(–stick) is arranged (to float) above the mine in a container. The (burning) of this joss stick determines the time at which the fuse is ignited, but without air its glowing would of course go out, so the container is connected with the mine by a (long) piece of goat's intestine (through which passes the fuse). At the upper end the (joss stick in the container) is kept floating by (an arrangement of) goose and wild–duck feathers, so that it moves up and down with the ripples of the water. On a dark (night) the mine is sent downstream (towards the enemy's ships), and when the joss stick has burnt down to the fuse, there is a great explosion.[86]

-

'Explosive bombs' (zha pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

A 'ground thunder explosive camp' (di lei zha ying) from the Huolongjing. The mine is composed of eight explosive charges held erect by two disc shaped frames.

-

Land mine system known as the 'divine ground damaging explosive ambush device' (di sha shen ji pao shi - mai fu shen ji) from the Huolongjing

-

Naval mine system known as the 'marine dragon-king' (shui di long wang pao) from the Huolongjing.

-

'Supreme pole combination land mine' from the Binglu

-

Steel wheel igniter from the Binglu

-

'Underground sky soaring thunder' from the Wubei Zhi

-

Steel wheel trigger mechanism from the Wubei Zhi

-

'Fire seed storage' (incandescent material) trigger mechanism from the Wubei Zhi

-

'Chaotic river dragon' from the Tiangong Kaiwu

No Alternative

A weapon called the "No Alternative" was used during the Battle of Lake Poyang. The No Alternative was "made from a circular reed mat about five inches around and seven feet long that was pasted over with red paper and bound together with silk and hemp— stuffed inside it was gunpowder twisted in with bullets and all kinds of [subsidiary] gunpowder weapons."[23] It was hung from a pole on the foremast, and when an enemy ship came into close range, the fuse was lit, and the weapon would supposedly fall onto the enemy ship, at which point things inside shot out "and burned everything to bits, with no hope of salvation."[23]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Andrade 2016, p. 201.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 334. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ a b c d "The Rise and Fall of Distinctive Composite-Metal Cannons Cast During the Ming-Qing Period". Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Lorge 2005, p. 134.

- ^ Swope 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 55.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 105.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 264. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 55-56.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 66.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 59-60.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e f Turnbull 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 70-72.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 158.

- ^ a b Chase 2003, p. 48-49. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChase2003 (help)

- ^ a b Chase 2003, p. 45. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChase2003 (help)

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 62.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Wei Yuan Pao (威遠砲), retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Da Jiang Jun Pao (大將軍砲), retrieved 30 October 2016

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 43. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChase2003 (help)

- ^ a b Lorge 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 112.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 92.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 97.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 363.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 98.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 339.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 99.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 100.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 101.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Cook 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Andrade 103.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 137.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 142.

- ^ a b Chase, Kenneth (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521822749.

- ^ de Abreu, António Graça (1991). "The Chinese, Gunpowder and the Portuguese". Review Of Culture. 2: 32–40.

- ^ Pelliot, Paul (1948). "Le Ḫōj̆a et le Sayyid Ḥusain de l'Histoire des Ming". T'oung Pao. 38: 81–292 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Fa Gong (發熕), retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Papelitzky 2017, p. 131.

- ^ Xiaodong, Yin (2008). "WESTERN CANNONS IN CHINA IN THE 16TH—17TH CENTURIES". Icon. 14: 41–61. JSTOR 23787161.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 171.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 172.

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 447–454. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, pp. 449–452. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 444. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 446. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 174.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 178-179.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 178-9.

- ^ Ye Meng Xiong's cannons, retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Breech-loading arquebuses of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Weatherproofed arquebuses of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Breech-loading arquebuses of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 11 February 2018

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 197.

- ^ 刘旭 (2004). 中国古代火药火器史 History of gunpowder and firearm in ancient China. 大象出版社. p. 84. ISBN 7534730287.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 202.

- ^ http://nautarch.tamu.edu/Theses/pdf-files/Hoskins-MA2004.pdf

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Distinctive Composite-Metal Cannons Cast During the Ming-Qing Period". Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 214.

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Unique weapon of the Ming Dynasty — Yi Wo Feng (一窩蜂), retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Rocket weaponry of the Ming Dynasty, retrieved 25 March 2018

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 178-187. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 196. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 197-199. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 199-203. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 203-205. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNeedham1986 (help)

References

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-60391-9

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 0-304-35270-5

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2 ed.). West Point, New York: Thomas Publications. ISBN 1-57747-079-6.

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0.

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-5259-9

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82274-2.

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0

- Cook, Haruko Taya (2000), Japan At War: An Oral History, Phoenix Press

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel.

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79158-8.

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen.

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 0-904040-13-5.

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43519-6

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing.

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on March 25, 2004.

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650-1830, UCL Press Limited

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd..

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 8791114128

- Lorge, Peter A. (2005), War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900-1795, Routledge

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29: 594–605

- May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reaktion Books

- McLahlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press.

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge At The University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. 5 pt. 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08573-X

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Ghengis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, vol. 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33733-0

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press.

- Papelitzky, Elke (2017), "Naval warfare of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644): A comparison between Chinese military texts and archaeological sources", in Rebecca O'Sullivan; Christina Marini; Julia Binnberg (eds.), Archaeological Approaches to Breaking Boundaries: Interaction, Integration & Division. Proceedings of the Graduate Archaeology at Oxford Conferences 2015–2016, Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, pp. 129–135.

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 0-87923-773-2

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen.

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-449-9

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea Ad 612-1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-478-7

- Turnbull, Stephen (2008), The Samurai Invasion of Korea 1592-98, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32736-X

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 0-06-093564-2

- Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997), Castles, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3

- Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975), Napoleon's Artillery, France: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0-85045-247-3

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Williams, Anthony G. (2000), Rapid Fire, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-84037-435-7