Clan of Ostoja

The Clan of Ostoja (old Polish: Ostoya) was a powerful group of knights and lords in late-medieval Europe. The clan encompassed families in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (including present-day Belarus and Ukraine), Hungary and Upper Hungary (now Slovakia), Transylvania, and Prussia. The clan crest is the Ostoja coat of arms,[1][2] and the battle cry is Ostoja ("Mainstay") or Hostoja ("Prevail"). The clan, of Alan origin, adopted the Royal-Sarmatian tamga draco (dragon) emblem.

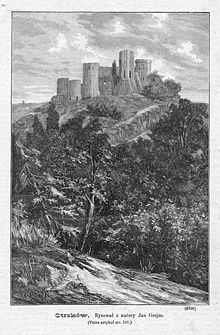

During the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the clan adopted several Lithuanian families, generally of Ruthenian princely origin, and transformed into a clan of landlords, senators and nobility.[3] Members of the clan worked together closely, often living close to each other. They held high positions, and held a great amount of land and properties in the Commonwealth and in Upper Hungary (today mostly present-day Slovakia) in medieval times, including many great gothic castles.[4] Members of clan Ostoja ruled several feudal lordships in Upper Hungary between 1390 and 1434 and Transylvania in 1395-1401 and again in 1410–1414, during the time of Duke Stibor of Stiboricz.[5][6][7]

A line of the clan which included relatives of Stibor of Stiboricz who followed him to Hungary was included in Hungarian aristocracy as Imperial Barons (Reichfreiherr) of the Hungarian kingdom in 1389. Stibor of Stiboricz and his son, Stibor of Beckov, were both members of the Order of the Dragon.[8] At the same time in Poland between 1390 and 1460, several members of clan Ostoja ruled Voivodeships and cities as castellans, voivods and senators on behalf of the king, and the clan was therefore in control of Pomerania, Kuyavia, and partly Greater Poland, which were a considerable part of the Kingdom of Poland at that time.[4]

The clan was involved in every war Poland participated in, and after the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth clan members can be seen in every independence movement and uprising, fighting against foreign forces. The clan put high value on education and were, in general, good administrators of their properties as well as the properties of the king (starostwa). They also included inventors, poets, scientists, and great diplomats.

Background

[edit]Polish clans and surnames

[edit]Polish clans, while having members related by male-line genealogy, also had many genealogically unrelated families, either because of families' formal adoption into various clans, or because of misattributions petrified in heraldic literature. The genealogically unrelated families were brought together in the Polish heraldic tradition through use of the same coat of arms and the same clan (coat-of-arms) appellation (name).

In contrast to other European countries, medieval Polish clans were unusually powerful compared to the Polish monarch. Though each clan was found in a certain territory, each clan also had family members in many other areas of Poland as they moved during medieval times also to settle down on the property(pl:posag) of their wife's or because they were assigned to settle down and serve the Crown, holding office and in some cases, were granted land in the area. Clan members supported each other in court sessions and in the battles, sharing same battle cry and later sharing same coat of arms. The powerful member was usually also the head of the clan, helping and caring for other clan members, calling for them when need for battle.[9][page needed]

Polish family names were appended with –cki or –ski in reference to the name of their properties; for example, if a person named Chelmski acquired the town of Poniec, he would change his surname to Poniecki.[10] Furthermore, Jerzykowski (de Jerzykowo) that owned property of Baranowo changed his surname to Baranowski (de Baranowo) and Baranowski that owned property of Chrzastowo change the surname to Chrzastowski (de Chrzastowo). The medieval Ostoja Clan seems to have been situated in more than 163 original nests and divergent locations, reflected in various surnames.[11] A clan became partly a name for the family members with different surnames.

Clan members could help both military and in the court, supporting each other in many different way.[12][13]

Chronology

[edit]Legendary origin

[edit]According to one legend,[14][15] the coat of arms was given in 1058 to a brave feudal knight, (Colonel) Ostoja, by Bolesław II the Generous. However, there may be another, older origin: Ostoja family members often used the name of Stibor (Scibor, Czcibor), on the basis of a family origin from Czcibor, victorious in the Battle of Cedynia brother of Mieszko I of Poland[16] – .

Piekosinski[3] indicates that the early crest of Ostoja was almost identical with the Piast dynasty crest. It has two "moons" and a cross, and the crest of the Piast dynasty was very similar, lacking the "moon" on top.

Another legend tells however that the Ostoja coat of arms origin from another brave Knight, Jan z Jani of Ostoja, first Polish voivode/duke of Pomerania and Gdańsk. Chased by a group Teutonic Knights, he had succeeded in crossing a river on horse despite being clad in full armor, and then raised his voice so the Lord would hear him and said "Ostałem" which means "I still stay" from which comes the name of Ostoja.[17] However, this legend is undermined by the term "Ostoja" being known far before the time of Jan z Jani.

Origin

[edit]

The Ostoja coat of arms evolved from Sarmatian tamga emblems.[18] The dragon in the Ostoja coat of arms relates to the Sarmatian dragon that had been used by Royal Sarmatians who, according to Strabo and Ptolemy, had lived in the area between Bessarabia and the lower Danube Valley and were descendants of the Royal Scythians.[19] This dragon was adopted by Roman legions and was used by Sarmatian cataphracts (armored heavy cavalry). The term draconarius was applied to the soldier who carried the draco standard.[19][20][21]

Early history

[edit]

The earliest historical records that mention the Clan use the name Stibor, which derives from Czcibor (Scibor, Czcibor, Cibor, Czesbor, Cidebur)[22] which comes from czcic (to honor) and borzyc (battle), thus denoting a person who “Battles for Honor” or who is the “Defender of Honor”.

An early Clan location is a village Sciborzyce, located in Lesser Poland that before 1252 was a property of Mikołaj of Ostoja. There are also notes about villages of Sciborowice and Stiborio (or Sthibor) around the same area in 1176 and 1178. Mikołaj of Ostoja ended building of the Roman church in Wysocice; on the walls of the church he cut an early sign of the Stibor family before it became a coat of arms that is called Ostoja. This sign is identical with the first known seal of Ostoja dated to 1381. Mikołaj's sons, Strachota and Stibor Sciborzyce to the church of Wysocice in 1252 and moved from Lesser Poland. Strachota moved to Mazovia and Stibor to Kujawy where in 1311 a note was found about a village called Sciborze, which become the nest of the kujawian line of Stibors that later become famous in Slovakia and Hungary.[23]

By 1025, when Mieszko II Lambert was crowned, the Kingdom of Poland had borders that resemble modern-day Poland. Many landlords (comes, comites) were against centralized power in the kingdom. Rivalry arose between the Lords of Greater Poland, whose capital was Poznań, and those of Lesser Poland, whose main city was Kraków.[24][25] The Stibors are thought to have been a mainstay of the Piast dynasty, Poland's first ruling dynasty. The Piasts[16] were able to expand Poland during the 10th and the beginning of the 11th century. Clan members were appointed commanding officers of the army units that protected and administered these new counties. The expansion of Poland and of Clan properties seem to have gone hand in hand; for example, when Kuyavia and Greater Poland (Wielkopolska) were incorporated, the Clan expanded into the same area. Records refer to Stibor as Comes of Poniec in 1099, and also refer to another Stibor as Comes of Jebleczna.[26] However, Poniec property belonged to the Crown in 11-12th century and information about Stibor of Poniec year 1099 seems not correct.

According to Tadeusz Manteuffel and Andrew Gorecki[27] the Clan consisted of people related by blood and descending from a common ancestor in early medieval time. Before the time of Mieszko I of Poland that united different tribes, the tribes were ruled by the Clan. During the time of Bolesław I Chrobry (967 – 17 June 1025) and Bolesław III Wrymouth clans included free mercenaries from different part of Europe but especially from Normandy to defend their properties and country. The original nests of the Ostoja family were situated in Lesser Poland and the Clan expanded north to Kujawy and Pomerania during the formation of the Polish state. It is possible that part of the families in the Clan of Ostoja also originated from free mercenaries, but most, Ostoja families originated from Royal Sarmatians, the Draconarius.

Before 1226 the Ostoja Battle Cry transformed to a coat of arms when the concept of heraldry came into prominent use in Poland. Knights began to have their shields and other equipment decorated with marks of identification. These marks and colors evolved into a way to identify the bearer as a member of a certain family or Clan. The dragon in Ostoja has been used and identified by the majority of Ostoja families since the 2nd century.

Late medieval period

[edit]

Because of several conflicts, the seniority principle was broken and the country divided into several principalities for over 200 years[28] until Wladyslaw I the Elbow-high[29] (Lokietek) was crowned King of Poland in 1320. Instead of duchies in the hands of the Piast dynasty, those duchies turned into several Voivodeship where the Voivode (Duke, Herzog, Count Palatine, Overlord) was appointed by the King and given to loyal landlords.[30][31] The last King of Poland from the Piast dynasty was the son of Wladyslaw I, Casimir III the Great, who died in 1370.

The Clan of Ostoja continued, during that time, to expand their land and was granted several high offices. Kraków replaced Poznań, the capital of Greater Poland, as the capital of Poland in 1039. The Clan expanded their land possessions mostly in the voivodeship of Kraków, Częstochowa and Sandomierz in the Lesser Poland region of Poland. Documents [32][33] tells about:

- Mikołaj of Ostoja - owner of village Sciborzyce, ended building of Roman church in Wysocice in 1232. His sign cut into the walls of the church is the oldest known sign of the family of Stibors of Ostoja that also became the Coat of Arms of the Clan of Ostoja.

- Piotr of Ostoja was Lord of the regality (starosta) of Sandomierz in 1259, and Miroslaw of Ostoja was Castellan of Sandomierz in 1270.

- Jan from Bobin was Treasurer and Chamberlain of Kraków in 1270 and Mikołaj of Ostoja was Chamberlain of Kraków in 1286.

- Comes Marcin of Ostoja in 1304 and in the family property of Chelm and Wola just outside Kraków city, furthermore there are notes about Comes Dobieslaw, Comes Sanzimir and Comes Imram, who were all great Lords belonging to the Ostoja family.

- Mikołaj of Ostoja hold high office as Standard-bearer of Inowrocław 1311 and of Wyszogród 1315, Jędrzej of Ostoja was Castellan of Poznań 1343.

- Moscic Stiboricz of Ostoja was Duke of Gniewkowo in 1353 and Lord of regality Starosta of Brzesko County 1368. He was from the line of Ostoja family that later became famous in Slovakia and Hungary, owner of family nest Ściborze in Kujawy and also father to future great Lord Stibor of Stiboricz.

- In 1257 the Clan of Ostoja founded the Roman church of St. Martin in Kraków together with the Gryf Clan family (see Gryf coat of arms).

Mongol and Tatar states in Europe were common at that time. In 1259, Poland faced a second Tatar raid that was supported by Russian and Lithuanian forces. The defense of the town and castle of Sandomierz was in the command by Lord castellan Piotr of Krepy from Ostoja. As the defense did not receive help from outside, the situation was hopeless for the defending side and finally Piotr and his brother Zbigniew were killed. The legend says that their blood then run down to the Vistula river and turned it red. A legend of the third Tatar raid tells how Lady Halina of Krepy, daughter of Lord Piotr of Sandomierz Castle[34] used a secret tunnel from the castle and duped the Tatars by telling them that she could lead them back through the secret tunnel right to the heart of the Castle.[35] The Tatar side verified that she had come through the secret tunnel, but she guided them deep inside the tunnel which was an extensive maze, and then released a white pigeon that she had with her to use as a prearranged signal. When the pigeon found its way out, the Polish closed the tunnel, trapping the Tatars.[36]

Empire of Ostoja 1370–1460

[edit] As Poland was under pressure from the west from the rising power of the Teutonic Knights, Poland turned east to ally with Lithuania. In 1386 Ladislaus II Jogaila (Wladyslaw II Jagiello) was crowned as King of Poland and his brother Vytautas (Witold) become Grand Duke of Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1410 Poland and Lithuania broke Teutonic domination in Prussia at the Battle of Grunwald and Tannenberg. The Union of Horodlo of 1413 declared the intent that the two nations cooperate. 47 Lithuanian families were adopted into 47 Polish clans, sharing the same coat of arms. This expansion eventually led to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was for a time the biggest confederated country in Europe. The Clan of Ostoja did not participate in the Union of Horodlo.[12]

As Poland was under pressure from the west from the rising power of the Teutonic Knights, Poland turned east to ally with Lithuania. In 1386 Ladislaus II Jogaila (Wladyslaw II Jagiello) was crowned as King of Poland and his brother Vytautas (Witold) become Grand Duke of Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1410 Poland and Lithuania broke Teutonic domination in Prussia at the Battle of Grunwald and Tannenberg. The Union of Horodlo of 1413 declared the intent that the two nations cooperate. 47 Lithuanian families were adopted into 47 Polish clans, sharing the same coat of arms. This expansion eventually led to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was for a time the biggest confederated country in Europe. The Clan of Ostoja did not participate in the Union of Horodlo.[12]

The Ostoja expansion went in parallel with the expansion of Poland and Lithuania. Some families were adopted into the clan in 1450.[37] In Pomerania, the powerful knight family of Janie owned several big land estates in the area and Jan z Jani became the first Voivode of Pomerania in 1454.[38]

Jan Długosz (1415–1480) was known as a Polish chronicle and was best known for Annales seu cronici incliti regni Poloniae (The Annals of Jan Długosz), covering events in southeastern Europe, but also in Western Europe, from 965 to 1480. In this work, he described Ostojas as brave and talkative.[39]

Between 1400 and 1450, many Ostojas attended the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, where Clan solidarity was very important.[40]

Around 1400 the Ostoja families owned over 250[41][42] properties in Poland, mainly in the area of Greater Poland and Kujawy, Kraków County, Częstochowa County and Sandomierz County with Kraków being the political center of Poland. As two families moved to Lithuania, one to Prussia and few more Lithuanian families was adopted including Russian Prince families like Palecki and Boratynski,[43] the Clan of Ostoja was standing on good economic and military ground. This together with high education and loyalty towards the Clan members made it possible to raise in power.

Poland

[edit]The list of offices that members of the Ostoja family held in the late medieval era[4] shows the power the Ostojas held, ruling a considerable part of Poland on the behalf of the King.

From the original nests and properties, members of the Clan of Ostoja created names of different branches of the Clan. All those properties and nests can be found within borders of Poland of today. The expansion of the Clan went both east, south and north, in the beginning of the 15th century Ostoja families also owned land in Pomerania, Prussia, Lithuania (including what is now Belarus), Ukraine, Moravia, Croatia, Transylvania, Upper Hungary and Germany. However, the biggest land area that the Clan owned was to be found in Upper Hungary (today mostly present-day Slovakia).[44]

The political and economical power of the Ostojas in Poland reached its peak at this time. As Jan z Jani lead Prussian confederation together with Mikołaj Szarlejski followed by excellent diplomatic work of Stibor de Poniec, the Clan was ruling in Pomerania, Kujavia and partly Greater Poland. Adding the power entrusted by the King to Piotr Chelmski, Jan Chelmski, Piotr of Gaj or Mikołaj Błociszewski, the Clan of Ostoja was among those that hold prime position in Poland at the time.[45][46][47]

Upper Hungary and Hungary

[edit]

The connection between Poland and Hungary is dated to the 12th century, when the Piast and Árpád dynasty were cooperating.[12] From that time royal families of both countries were family related through several marriages between ruling houses. It was therefore easy to find Hungarian nobles in Poland and Polish nobles in Hungary and Slovakia. Abel Biel was the first of the Ostojas to serve on the Hungarian Court, and was also the first to receive land in Upper Hungary.[48]

Most of the Ostoja families supported the House of Anjou on Polish throne and when Luis I the Great entered the Polish throne in 1370 after Casimir III the Great, it made it possible for the Clan of Ostoja to expand south.[49] Hungary at that time was a modern and expansive kingdom, after Italy it was the first European country where the renaissance appeared. When Luis the Great died without a male heir some anarchy broke out in both the Kingdom of Poland and the Hungarian Empire. The Ostoja families continued to support the House of Anjou on both the Polish and Hungarian thrones. This did however not happen since Poland chose to ally with Lithuania and elected Ladislaus Jogaila to the Polish throne.[12]

Stibor of Stiboricz and Sigismund von Luxemburg

[edit]

Stibor of Stiboricz (1347–1414) of the Clan of Ostoja, son of Moscic Stiboricz (Duke of Gniewkowo), held the position of Lord of regality (Starosta) of Brzesc as he also served Louis I of Hungary but when the King died, he lost the position as Starost of Brzesk because of his support the House of Anjou and left Poland for Hungary.[50] Although Stibor received office of Lord of the regality (Starost) of Kuyavia in 1383, he turned to help his friend Sigismund von Luxemburg (later Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor) on Hungarian throne 1386 and become his most loyal ally.[51]

Sigismund was the Prince of Brandenburg before rising to the Hungarian throne. He later became Holy Roman Emperor, King of Germany, Bohemia, Hungary (including present-day Slovakia, Balkan states, Romanian and Bulgarian lands), Italian republics and Prince of Luxembourg. At the age of 13, he was sent to Kraków in order to study Polish language and customs. He married Mary, daughter of Louis the Great and became one of the most powerful Emperors in Europe.[52]

In Poland, as Stibor of Stiboricz recognized the competitors of Jogaila on Polish throne, he immediately entered Poland with an army of 12,000 men, commanded by Sigismund von Luxemburg, to assure that younger sister of Mary, Queen of Hungary, would mary Ladislaus Jogaila and end the battle for Polish Crown. 1384 Jadwiga was Crowned as Queen of Poland and in 1386 Jogaila married her and became King of Poland.[44]

Sigismund recognized Stibor of Stiboricz as his most loyal friend and adviser. In 1387 he granted Stibor the position as Master of Hungarian Court and also the Governor of Galicia (Eastern Europe). The King gave also Stibor the exclusive right to receive high offices in the Empire. In 1395, Stibor became Duke of Transylvania, a nomination that made him lord of a big part of the Romania of today.[53]

In 1396 Sigismund led the combined armies of Christendom against the Ottoman Empire. The Christians were defeated at the Battle of Nicopolis. Stibor of Stiboricz, one of the generals and commanders of the army, rescued Sigismund, who was in great danger while retreating from the battlefield.[44]

In May 1410, King Sigismund entrusted Stibor and the Palatine Nicholas II Garay to mediate between the Teutonic Knights and King Władysław II of Poland, but when negotiations failed, war broke out. The Battle of Grunwald took place, with almost all of the Ostojas leaving Hungary to join Polish forces. At the end of 1411, Stibor, his brothers and other members of the Clan of Ostoja was in charge of leading troops to fight against the Venetian Republic in Friuli. In 1412 Stibor was meeting with Zawisza Czarny (The Black Knight) in his Castle of Stará Ľubovňa in Slovakia, preparing the negotiation between Sigismund and Polish King Vladislav Jogaila, which ended with the Treaty of Lubowla.[54]

Stibor proved to be a great diplomat who combined loyalty to King Sigismund with his diplomatic work on behalf of Poland. In 1397 Sigismund chose Stibor as his representative in negotiations with the Polish King Jogaila, who appointed Mikołaj Bydgoski to represent Polish Crown. Thus the two brothers, Stibor and Mikołaj, met as leaders of their respective diplomatic delegations. Later on, around 1409, King Jogaila appointed his most trusted diplomat Mikołaj Błociszewski of the Clan of Ostoja to lead the negotiations.

In the end, it was the Clan of Ostoja that was the leading force in breaking down Teutonic side, they did it not only by using fine art of sword but also with outstanding diplomatic skills.[55][56]

Land and nominations

[edit]In 1388 King Sigismund granted Stibor the Beckov and Uhrovec castles in Upper Hungary. In 1389 Stibor also became the Ispán of the Pozsony County, including the Bratislava Castle, where he appointed a castellan to administer the property. He also was granted the town Nové Mesto nad Váhom.[56][57]

In 1392 Stibor became the Ispán of the Trencsén and Nyitra counties, where he appointed clan members as castellans of the county. Furthermore, Stibor was granted the possession of Csejte and Holics (Čachtice and Holíč in present-day Slovakia). In 1394 he received Berencs, Detrekő, Éleskő, Jókő and Korlátkő castles, which are respectively modern Branč, Plaveč, Ostrý Kameň Castle, Dobrá Voda castle and Korlátka, also in Upper Hungary. In 1395 he became the Voivode of Transylvania and in 1403 he was entrusted to govern the possessions of the Archdiocese of Esztergom and the Diocese of Eger.[56][57]

Stibor was one of the founding members of the very exclusive Order of the Dragon in 1408, which consisted of European royals and powerful princes as well as some of most distinguished Hungarian Lords. In 1409, Stibor was reappointed Voivode of Transylvania, and was recognized as Duke of Transylvania.[58][59][60][61][62]

Altogether, Stibor of Stiboricz was – together with his son - Ispán of several counties, Prince of Galizia, Duke of Transylvania, owner of over 300 villages, towns which in total was about half of western Slovakia of today.[63] He was owner of 31 castles and in control of a further five[64] in Upper Hungary, many of which could be found along all the 409 km-long Vah river. Because of that, Stibor stiled himself “Lord of whole Vah”. He was governor of Archdiocese of Esztergom, Diocese of Eger, Master of Hungarian Court, closest friend and adviser to the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. Adding the land, Castles and nominations that was granted to the Clan, close family of Stibor and the fact that Stibor of Stiboricz gave all important offices in his power almost only to family and Clan members, the Clan of Ostoja was in a strong position at the time.

Close family of Stibor of Stiboricz[54][65][66][67]

The castles that the clan received in Upper Hungary were of great importance as they controlled the borders, Vah river and important roads. They were all built to give good defense against an enemy. Inside the strongholds, the clan had own army unites, their upkeep was paid from the income Ostojas gained from their land that they owned or controlled. They could also afford to hire mercenaries when necessary and they were in close cooperation with each other, often visiting and helping to maintain the power they have been given. All of them were in possession of land that was much bigger than any of the clan members had in Poland.

Although Sigismund's most loyal Stibors were not to help him anymore, the presence of the Clan in Upper Hungary was still significant. The testament told that the fortune of the Stibors was to be passed to the closest family which included children and grandchildren of Stibor of Stiboricz's brothers, all except the Beckov Castle with belongings that were supposed to be given to Katarina, daughter to Stibor Stiboric of Beckov.[68] This testament was approved by the emperor Sigismund and his wife, the queen. The testament of his son, Stibor of Beckov, was in line with his father's, but with one important difference. It was written 4 August 1431 and the difference in the testament from his father's wish told that in case Stibor of Beckov did not have a son, all the properties that he personally owned would pass to his daughter Katarina. This however was under the condition that she would marry Przemyslaus II, Duke of Cieszyn of the Piast dynasty. In case of his death, Katarina was to marry his brother. If the marriage of Kararina and Duke Przemyslaus II did not result in any heir, all the properties would go back to the close family of Scibor of Beckov, as in the testament of his father. By this marriage, the Stibors of Ostoja would have dynastic claims in case of extinction of the Piast Dynasty in the future.[69]

Fighting many wars with Ottoman Empire could not stop the Turkish side to grow and take more land in east, west and south. Sigismund found himself in a difficult position. He already took a loan from Polish king when signing the Treaty of Lubovla but the royal coffers were empty since he used every penny in the war against rebellious Venice. Since he could not pay back the loan given by Polish king, he lost 16 towns in Spiš area to Polish side.[70]

Emperor Sigismund saw his enemies expanding in almost every direction. The Ottoman Empire in the east, Italian republics in south, the Hussite threat in north. However, the pact with Albert II of Germany that was supposed to marry Elizabeth of Luxembourg, the daughter and heiress of Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, and the pact with the Clan of Ostoja was protecting north side of the Kingdom. And through marriage between Katarina of Beckov and the Duke Przemyslaw of the Piast dynasty, the Kingdom could count on more support in the battle against Hussite side. It was all set to form powerful coalition. As Albert II would be the successor on the Hungarian throne and the Clan of Ostoja would hold the position in Upper Hungary and south of Poland together with the Piast dynasty, the focus could then be to stop Ottoman Empire to expand more in west direction.[71]

Stibor of Beckov

[edit]

His son Stibor of Beckov (also known as Stibor II), continued his father's work and succeeded in extending land holdings further. He was also appointed Lord of Árva County including Orava (castle) and was also a member of the Order of the Dragon. The son of Stibor's brother Andrzej, also known as Stibor, was the Bishop of Eger in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Eger. When Sigismund took the nomination from him, he moved back to Poland but never accepted Sigismund's decision, ultimately calling himself Bishop of Eger to the end of his life. Although he was granted several nominations in Poland and held several properties, they could never match the properties that he was in charge of in Hungary.[66]

In 1407 Stefan of the Wawrzyniec line of Ostoja moved to Upper Hungary where Stibor gave him the position of Castellan of Košecy. In 1415 he was in charge of the whole Trencsén on the behalf of Stibor. He expanded his properties with Ladce, Horné and Dolné Kočkovce, Nosice and Milochov which he left to his six sons.

Stibor of Stiboricz died in 1414 and was supposedly laid to rest in his own chapel inside St. Catherine's Church in Kraków. This was also supposedly the resting place for his son. It was also written that both father and son were buried in the chapel until 1903 when a grave of red marble stone was found in Buda. This was of Stibor Stiboric of Beckov, dated to 1431. In recent times, a grave was found in Székesfehérvár which had been broken into pieces as a result of Turkish destruction. However, it has now been established that this was the grave of Stibor of Stiboricz. It was made of the same stone, red marmor and when the piece of coat of arms was finally found and there was no doubt. Stibor was granted a place beside other members of the Hungarian royalty.[72]

Since Stibor of Beckov (died 1434) did not have any heirs who could inherit existing properties, the testament told that it would be passed onto the closest family, including Beckov Castle that was made as power center of the clan in Upper Hungary. This Castle was made to be one of the most significant residences of that time, including great paintings, sculptures and chapel that was formed by artist from many different countries.[73] Several testaments have been approved by the Emperor Sigismund and also his wife. The main issue in those was that all the properties of the Stibors in the kingdom of Hungary would be divided by closest family in case of lack of hair in the line. In that way, the land would stay in family hands.[74]

Unfortunately, Stibor de Beckov died suddenly in battle against Hussite forces soon after the agreement between Emperor Sigismund, Albert II of Germany and the Piast dynasty had been made. Just a few weeks later, a peace agreement with the Hussites was signed. It was now up to Katarina to marry Duke Przemyslaw II in accordance with her father's wish. However, this was not to happen as Katarina later married Lord Pál Bánffy of Alsolindva. Soon after, Stibor the Bishop of Eger lost his office and the Wawrzyniec lost all their offices and properties including the Castle of Košecy (which had previously been granted by Stibor of Stiboricz). All this was a result of their support for the Hussites. According to the testament, all lands possessed by the Ostoja clan in Upper Hungary was to be passed to the closest family of Stibor.

Mikołaj Szarlejski

[edit]When all hereditary lines mentioned with the testament became extinct, Mikołaj Szarlejski inherited all the land holdings and properties. He was the son of Mikołaj Bydgoski, Lord castellan of Bydgoszcz and brother of Stibor of Stiboricz. Szarlejski was, at the time of the death of Stibor of Beckov, the Commander of the Polish forces in Prussia as well as Voivode of Brzesc-Kujawy. Besides this, he was also lord of several regalities and ultimately one of the most powerful and influential lords within Poland. However, Szarlejski supported the Hussites and was undertaking several hostile raids on Hungarian properties and strongholds which was not in accordance with the policy of the family. Since the land of Ostoja in Slovakia was the primary defense against the Hussites, it would now be in hands of the enemy. In this situation and because Katarina did not marry her Prince of Piast, Emperor Sigismund gave orders to the Hungarian Court to cancel the testament of Stibor of Beckov. The testament was cancelled on 28 March 1435.[75]

Mindful of Stibor's past loyalty and friendship, Sigismund did not leave Katarina of Beckov without financial support. She received one-fourth of the value of all properties in cash. Also on the day of his death, Sigismund gave Beckov Castle and belongings to Pál Bánffy. This was under the condition that he marry Katarina which was also fulfilled. Although Katarina received only 25% of the total property value, this some was considered significant but did not stay in the Ostoja family.[76]

In 1440 Władysław III of the Jagiellon dynasty assumed the Hungarian throne and for 4 years he was king of both Poland and Hungary. However, he died in the Battle of Varna and his brother Casimir IV Jagiellon became King of Poland in 1447. Casimir married Elisabeth of Austria (1436–1505), daughter of the late King of Hungary Albert II of Germany and Elizabeth of Luxembourg (daughter of Sigismund, the Emperor and King of Hungary). The Jagiellon House challenged the House of Habsburg in Bohemia and Slovakia.

Following the death of Albert II of Germany in 1439 when defending Hungary against Turks, Mikołaj Szarlejski recognized opportunity to regain the land of his family and the Clan in Slovakia. Szarlejski tried to convince Hungarian Royal Council that family properties have been taken in violation of the law. However, Hungarian Lords and Royal Council in Hungary had no intention to give back all of the north defence to their enemy. Then in 1439 Szarlejski decided to raise army against Hungary. With help of the Hussite side, he succeeded to siege several strongholds in the Vah area. Supported by Jan de Jani of Ostoja, the Voivode of Pomerania and Gdańsk and several other powerful Lords from the Clan of Ostoja and with support of many friends, the war against Hungarian Empire and Germany was in the beginning successful. Unfortunately, Szarlejski although being in charge of Polish forces in Prussia, did not have any significant commanding talent[77] and ironically, both Stibor of Stiboricz and his son Stibor Stiboric of Beckov made great improvements in the fortification of their Castles which made siege of many of them almost impossible. Beckov Castle would later hold siege from Turkish side about 100 years later. As result of that and because the enemy was too strong, military action failed.[78]

The line of Stibor of Stiboricz was extinct, other lines of Stibor's family that derived from Stibor of Stiboricz brothers and that was called Stiborici in Hungaria (the Barons of Hungarian Kingdom)[79] was also extinct. Szarlejski had no heir of his own and his large properties in Poland was past to the Kościelecki family of Ogończyk Clan[80] as the daughter of Stibor Jedrzny married Jan Kościelecki, close friend and ally of Szarlejski. Economic power of Jan de Jani was broken because of all wars with Teutonic knights that he had to pay for himself and all the lines of the Moscic of Stiboricz (Stibor of Stiboricz's father) was extinct. However, other lines of the Clan that still was considered as close family to the Stibors was in position to be the successors of the land in Slovakia in case of death of Szarlejski.

Stibor of Poniec

[edit]

The great diplomatic work achieved by Stibor and Mikołaj was to be continued by Stibor of Poniec some 50 years later. He raised funds in Gdańsk (Danzig) for a campaign against the Teutonic Knights who held Malbork (Marieburg). The Teutonic Knights had financial difficulties at this time and were in great debt to the bulk of their main defensive force which consisted of Czech/Moravian mercenaries. Using the money from Gdańsk, Stibor de Poniec was able to persuade the mercenaries to leave the stronghold and he took control of Malbork without battle; King Casimir IV Jagiellon entered the castle in 1457.[81] This led to the Second Treaty of Thorn, sealed in 1466 by Sibor of Poniec. Furthermore, he negotiated on behalf of the Polish king with Denmark which had supported the Teutonic Knights, and succeeded in ending a Danish blockade on Polish commerce in the Baltic Sea.[55] Other members of the Clan of Ostoja were also recognized as formidable knights in the conflict against the Teutonic Order.

Stefan of Liesková (Leski) of Wawrzyniec line of Ostoja

[edit]Stefan of Liesková (Leski) of the Wawrzyniec line of the Clan had six sons. All their properties in Hungary were confiscated in 1462 by Matthias Corvinus of Hungary because of their support for the Hussites. Košeca together with all other properties were given instead to the Mad’ar (Magyar) family that were fighting against the Hussites at the time. In 1467, Wawrzyniec and his Hussite allies successfully repossessed Košeca Castle but shortly after lost control again to the Hungarians. The Mad’ar family became extinct in 1491 and Košeca Castle with other properties were given to the Zápolya family in 1496. At that time the Jagiellon dynasty were kings of both Poland–Lithuania and Hungary. The Wawrzyniec line protested against the Zápolya family being in possession of their properties, however, the Zápolya family were too powerful and also hereditary-linked with the Jagiellons since Barbara Zapolya became Queen of Poland in 1512 and Jan Zapolya (János Szapolyai) became King of Hungary in 1526.[82]

Also in Poland, the Wawrzyniec line of Ostoja together with other members of the Clan, claimed the property of Szarlejski that passed to Kościelecki as well as Janski (de Jani) family claimed compensation from the King but also here the resistance was great big and finally they gave up plans to reclaim these properties.

Aftermath

[edit]Ostoja landholdings were extensive and were a source of power. The Stibors in Slovakia were one of the most powerful families in Europe. Comparing with the Habsburg dynasty, the Clan had good chance to challenge if they would stay united and with the Stibors as leading force in Upper Hungary. However, it was necessary for the Stibors to be related with ruling dynasties or those that have been ruling to be able to claim power in the future. Marriage with prime families of central Europe was not enough. The family needed to be connected with royal blood. Instead of challenging Habsburgs, Stibor of Beckov and the Clan of Ostoja made agreement of cooperation which would benefit both sides. Both sides had equal forces and before Albert II of Germany become king of Hungary, Stibor of Stiboricz successfully challenge Austria, burning down the country to the ground except for Vienna that he left alone.[54]

Lack of heirs that could continue politics of the Clan successfully was also part of the reason of economical problems. While in most countries properties was past to younger lines in the family, in Poland women have same rights to inherit the properties as males. Since all main lines of the Clan suddenly faced lack of males at same time, it were the daughters that inherited the properties and brought them into other families through marriage. As did Katarina when she married Pal Banffy. The Banffy family inherited all the founds given to Katarina by the Emperor Sigismund when giving her 1/4 of all property value in cash. The Beckov castle was in the hands of the Banffy until also this family became extinct and Beckov returned to the Hungarian Crown.[83]

Finally, it was coordinated politics of the Clan of Ostoja that made it powerful. It was also Szarlejski's own politics that in the end ruined family power in Slovakia. Although the Clan supported Poland against Teutonic Knights, they did not support the Jagiellon dynasty in the beginning as the kings of Poland. Clan members staying and living in Poland was however granted power by Jagiellon kings in return for their support. In many cases, the Clan was forced to raise funds from their own treasury in order to defend Polish borders.[84] In the end, it was during the reign of the Jagiellon dynasty, the Clan of Ostoja lost its power and all doubts that the Clan had against those kings from the beginning, become very true. Also in Hungarian history, Jagiellon dynasty have been described as weak and incompetent, which was the result of the politics of the Lords of Lesser Poland as they were responsible of electing kings who would sign documents in favor of their financial ambitions rather than choosing strong kings with benefit for the kingdom.[85]

As the main properties in both Slovakia and Poland were finally lost, the economic power was broken and the Clan of Ostoja was outside the politics of Poland for next 100 years,[86] concentrating mostly in increasing their land properties, holding offices on local level.

Commonwealth era

[edit]

In the late medieval period, the Clan set out rebuilding the power base that had been weakened through attrition of its senior lines. In 1450, the Clan adopted families of powerful knights, leading provincial nobility, and several princes.

The Union of Horodło of 1413 initiated a significant drive toward unification of Polish and Lithuanian nobility and clergy. 47 prominent Catholic Lithuanian (including Ruthenian) families were symbolically adopted into 47 Polish clans. Subsequently, several other families from the east joined the Clan structure in the next adoption wave in 1450. These Lithuanian (including Ruthenian) nobility were granted the same rights as their Polish equivalents. Piekosinski provides a list of adopted families as well as families that received nobility.[87] It appears that no more than 20 families in total joined the Clan of Ostoja in 1450.[88]

At the end of 15th and beginning of the 16th century the Commonwealth was the biggest and one of the most powerful countries in Europe. In 1569, the Union of Lublin created a real union of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, replacing the personal union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It encompassed territories from Poland, Lithuania (including what is now Belarus), Prussia, what is now Latvia, Ukraine, Podolia, part of Spisz and part of Russia including Smolensk.

The Union of Lublin marked the end of a 150 years period of Commonwealth expansion and consolidation. The skills needed to expand and secure national borders were different from what was required when the expansion was completed. The new nation needed new kind of administration, and as new goals become paramount the age of brave knights passed. Clan organization lost importance, and interfamilial cooperation lessened.

Throughout the Commonwealth, the administrative structure was generally similar, albeit with some important differences. In Poland, the use of titles by the nobility was formally discontinued by the constitution of 1638, the nobility being equal according to the law, which was confirmed in 1641 and 1673.[89] However, in actual practice families with close descent from the major dynastic origins such as the Ostoja families of Stibor line or some to the Clan adopted families, who had held important positions in Poland during medieval times and thus held titles such as comes or dux (duke, voivode, count palatine) never accepted the equality system and they continued to utilize their titles, particularly when traveling abroad or on diplomatic missions.

The titles were in the 13th century used during the lifetime but it was common to pas it to next generation although according to the law, all nobility had equal rights and hold equal rank. Looking for influential families in Poland, one must look for the senatorial position and not the titles that have been given to Poles during the partition time of the Commonwealth. Those families were never equal to simple noblemen or knights but more equal to English peers, with the difference that the title was inherited by all members of the family, not only the oldest son like it is in England. All of those old and powerful medieval families that played central role in building Polish Empire was part of hereditary High Nobility.[90] Knights that became part of the Clan of Ostoja in medieval times were never equal to the mighty Lords of Ostoja but were in the 14th and 15th century given rights equal to medieval German Baron that origin from knights and in time also become in function more like German Freiherr.[91]

Magnates of the Commonwealth were the wealthiest dynastic families with particularly large landholdings.[92]

Magnates of the Commonwealth are often called the aristocracy of the Commonwealth but the definition of what constitutes aristocracy differs from the rest of Europe in that the Magnate families were much more powerful, often comparable to Princes. A good example is the extinct family of Pac[93] that ruled the Duchy of Lithuania in the 17th century. The Pac family had not descended from a Prince, and therefore did not use any title at all. During the partition of the Commonwealth the Pac family received the title of Count. However, when looking at the size of the Pac properties and their position in the Commonwealth, a simple Count title seems not adequate to their power and property size that was far beyond imagination of most of the European Lords.[94]

Partly in Poland but certainly in Grand Dutchy of Lithuania and Ukraine, almost all important positions was in the hands of the Magnates and it was passed through generations. The only question was which of those about 20 great Magnate families would rule most Voivodeship, Counties and Provinces. The list of those Magnates during the days of the Commonwealth include following families:[94][95]

Princely Houses: Radziwill, Sapieha, Wisniowiecki, Lubomirski, Czartoryski, Ostrogski, Sanguszko. Other Magnat families: Chodkiewicz, Pac, Tyszkiewicz, Zamoyski, Hlebowicz (without any hereditary title), Mniszech, Potocki.

Those families had most significant impact on the politics of the Commonwealth. They chose the candidate for the King and they made sure that the candidate was chosen to serve their interest. The nobility voted for the candidate that Magnates and other aristocracy told them to vote on. The Magnates became the true power in the Commonwealth and the King was, with some few exceptions, only a Marionette of the Magnates in their political game.

Furthermore, there were then some 50-60 influential and very wealthy families and with great family history, sometimes with Prince titles. However, those families did not have same impact on the politics of the Commonwealth, still being considered as Magnats of the Commonwealth. Among them there are most magnificent families like Lanckoronski, Tarnowski, Tęczyński, Prince Holszanski, Rzewuski, Gonzaga-Myszkowski or Prince Czertwertynski.[94]

The next 300-400 families (of in total tens of thousands of noble families[96]) counting in power and land possession in the Commonwetlh could more likely be equal to the European aristocracy when referring to counts and barons. Those families should also be included as aristocrats but most publications[97] refer only to titled nobility as the aristocracy which is not in accordance with Polish rank system during the time of the Commonwealth. There were many wealthy and influential families that hold several offices in the family like Voivode, Castellan, Bishop or Hetman which gave them a place in the Senat of the Commonwealth. This group hold many great families like Sieniawski, Arciszewski, Ossolinski, Koniecpolski, Prince Giedrojc and finally also many families included in the Clan of Ostoja.[98]

According to the Etymological Dictionary of the Polish Language, "a proper magnate should be able to trace noble ancestors back for many generations and own at least 20 villages or estates. He should also hold a major office in the Commonwealth". By this definition, the number of magnates in the Clan of Ostoja is high.

Aristocratic titles given to noble families in the time of partition of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by Russian, Prussian and Austrian emperors as well as by the Holy Vatican City State cannot be compared with the titles from medieval times. Those are, except single cases, foreign titles. The constitution of 1921 (§96) in March, removed all the titles in Poland including the nobility itself. However, the constitution of 1935, did not confirm paragraph 96 in the constitution of 1921. Therefore, families that received or bought titles from foreign Emperors could still legally use them. As the titles were not legally forbidden, the peerage of old families in Poland was also taken into consideration. However, usually when referring to titles in Poland, this is understood to mean the titles given during the partition.[99]

In this way, families included in the Clan of Ostoja and having origin from medieval time, are all considered as High Nobility.

16th century

[edit]

Polish Ostoja families almost totally disappeared from political life in the 16th century. Nevertheless, the late 16th century features some notable Clan members. Kacper Karliński, Lord castellan of Olsztyn, is known for his legendary defence of the town in 1587. Maciej Kawęczyński reformed the printing system in Lithuania. Mikołaj Kreza was Rittmeister of the Crown. Michał Maleczkowski was Magnus procurator (Latin for "ruler") of Lesser Poland 1576–1577. Gabriel Słoński (1520–1598) was architect and Burgrave of Kraków.[100]

17th century

[edit]

The 17th century provided much more activity from the Clan. First half of the century was the Golden Age of the Commonwealth. In Lithuania families were fighting for supremacy in the Grand Duchy which led to many confrontations. The leading families were those of Prince Radziwiłł, Prince Sapieha and Pac.[101] In Volyn, Podole and Ukraine the Wisniowiecki family reached the supremacy of the area. The estimated number of people working for Wisniowiecki on his estates was almost 300,000[102] at that time.

In Lithuania, the Sluszka and Unichowski families of the Clan of Ostoja raised in great power. Krzysztof Słuszka became Voivode of Livonia and Aleksander Słuszka Castellan of Samogitia and later Voivide of Minsk, then Voivode of Novogrod and ended as Voivode of Trakai in 1647. Samuel Unichowski of Ostoja followed up 40 years later and also became the Voivode of Trakai. Lady Elżbieta Słuszka (1619–1671) was the richest and most powerful Lady of the Commonwealth.[103] She was the Crown Court Marshall and after the death of her first husband inherited the Kazanowski Palace in Warsaw. Josef Bogusław Sluszka (1652–1701) was Hetman and Castellan of Trakai and Vilnius. Dominik Michał Słuszka (1655–1713) was the Voivode of Polotsk and finally Aleksander Jozef Unichowski became the Castellan of Samogitia.[4]

Other families in Lithuania that were part of the Clan of Ostoja became very wealthy. Prince Boratynski's family joined the Clan[104] already in 1450 and was often holding high military rank. Prince Palecki's family also joined at the same time. The Danielewicz family was included in the Pac family by adoption of Michał Danielewicz, son of Katarzyna Pac (daughter of Voivode of Trakai) and inherited part of their great land possessions including Bohdanow and the town of Kretinga.[105]

In Poland, the Szyszkowski family of Ostoja became very powerful. Piotr Szyszkowski was the Catellan of Wojno 1643, Marcin Szyszkowski was the Bishop of Kraków and Prince of Siewierz and Mikołaj Szyszkowski became the Prince-bishop of Warmia in 1633.[4] Both Prince Mikołaj and Prince Marcin had great impact on the politics of the Commonwealth. Following information is mainly taken from Polish Wikipedia.

Salomon Rysiński (1565–1625) was famous writer at the time, Krzysztof Boguszewski was one of the most famous painters and artists of Greater Poland and Stanisław Bzowski (1567–1637) was member of Dominican Order, friend of reforms, appointed by Vatikan City to write down its history.

Wojciech Gajewski was the Castellan of Rogozin 1631–1641, Łukasz Gajewski became Castellan of Santok in 1661, Michał Scibor-Rylski the Castellan of Gostyn in 1685, Mikołaj Scibor Marchocki, the Castellan of Malogoski (Żarnòw) 1697 and Jan Stachurski was leading the army against the Cossack uprising as major general in 1664.

The most famous Clan members in that century were Kazimierz Siemienowicz, General of artillery, military engineer, artillery specialist and the pioneer of rocketry, whose publication was for 200 years used as the main artillery manual in Europe,[106] and Michał Sędziwój (Michael Sendivogius, Sędzimir) (1566–1636), from the Sędzimir branch of the Clan, was a famous European alchemist, philosopher and medical doctor. A pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemical compounds. He discovered that air is not a single substance and contains a life-giving substance-later called oxygen-170 years before Scheele and Priestley. He correctly identified this 'food of life' with the gas (also oxygen) given off by heating nitre (saltpetre). This substance, the 'central nitre', had a central position in Sędziwój's schema of the universe.[107] Sędziwój was famous in Europe, and was widely sought after as he declared that he could make gold from quicksilver, which would have been a useful talent. During a demonstration on how to make the gold, in presence of the Emperor Rudolph II, Sędziwój was captured and robbed by a German alchemist named Muhlenfels who had conspired with the German prince, Brodowski, to steal Sędziwój's secret.

18th century

[edit]

The 18th century Commonwealth suffered from a series of incompetent kings of foreign origin whose main interest was fighting personal wars against other countries.[12] Persistent wars and general turmoil bankrupted the national finances, and many power-hungry Magnates cooperated with foreign forces. The last king, Poniatowski, was paid by Catherine II of Russia and was obliged to report to Russian ambassador Otto Magnus von Stackelberg.[12] He was furthermore richly paid to facilitate the constitution of May 3, 1791 but because of his character or rather lack of it, he did not fulfill his promise.[109] On the other hand, Poniatowski did care about cultural life in Poland, supported necessary education of young patriots and also did not go against members of the Bar confederation.

Most families that signed Poniatowski's election, including many Ostoja families, were signing for the Czartoryski family who wanted to make necessary changes in the Commonwealth.[110] However, to support those changes Czartoryski asked for help from Russia, an offer that Russia could not resist.

At the beginning of the period, the Ostoja families in Lithuania and Poland avoided engagement in this political chaos. The king was appointing those that supported his own ambitions, which was the beginning of some new great fortunes. This political disaster ended in Partitions of Poland, 1772 when Prussia, Austria and Russia decided to divide defenseless Commonwealth between them. Poniatowski's reign until 1795 became the darkest chapter in Polish history.[109] The Constitution of May 3, 1791 came far too late. This was the first time that the Commonwealth included Ruthenians and not just Poland and Lithuania. New Commonwealth was to be formed of three nations. Also this intention came far too late. However, the Constitution of May 3 united families that wanted to make necessary changes and that would serve the nation. In this movement we suddenly see lot of activity from the Ostoja families.[111] Almost all of them supported the movement and in many cases all members of the family joined, women and men. In the first half of the century, the Ostoja families hold many offices and was still prospecting. In the second half of the century, they clearly turned into military commanders and supporters of the resistance, leading Confederations and armies against foreign forces and specially against Russia.

Ignacy Ścibor Marchocki of Ostoja (1755–1827) created famous "Kingdom of Mińkowce".[112] Marchocki proclaimed his estates an independent state and installed on its borders pillars with the name plates, identifying that this is "The border of Minkowce state". The "Kingdom" hold one town, 18 villages and 4 Castles (one for each season) with some 4200 souls living in the "Kingdom". Marchocki liberated peasants from serfdom, granted them self-government, established jury (court with jury and court of appeal), built school, pharmacy, orphanage, churches and monuments, cloth and carriage factories, factory of anis apple oil production, with brickyard, varnish and paint plants, with mulberry trees gardens. Its own paper was manufactured there and lime – calcined. He opened his own printing house, where different decrees (like "agreement between the Lord and the peasants"), directions, resolutions and even sermons, later delivered by him in Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. The government of the Kingdom that included Jews, serfs, town citizens, peasants and foreigners.[112] He also employed two doctors within the property. The central body of the State was the County Court as well as Court of Appeal. The main thing in the State was to give all citizens equal legal rights.

All of this was of course reported to Russian Administration that in the beginning was stunned, thinking that it was an act of madness. However, the "Kingdom" was working excellent and the Lord of the Kingdom was getting richer and more famous, buying even more properties and land to expand the "Kingdom" including 40.000 ha land around Odessa. Life inside his estate was considered as heaven comparing to normal life peasants outside the border pillars which would more correctly be referred as hell. Peasants was at that time normally property of the estate that could be sold any time. In the "Kingdom" people was living in wealth and prosperity and Marchocki himself was the most successful administrator of his goods in Russian Empire.[113] This eccentric man was summertime wearing a Roman Toga during official meetings on the property that looked like picture taken from paradise.

In the end, this started to worry Russian administration that gave order to burn down all the printing so this madness would not spread to other provinces. This could cause a revolution because suddenly it was clear that making democracy inside a property was making owners rich and people happy. Soon, every citizen of not noble origin in the area wanted to live in the "Kingdom of Mińkowce". It was a plague that started to spread all over the countryside and infect entire system. To stop this revolution, the Tsar ordered Marchocki captured and imprisoned.[112][113] Following information and source is taken from Polish Wikipedia.

Lady Krystyna Ścibor-Bogusławska (d. 1783) - was Lady of regality of Wągłczew by nomination received by the King Poniatowski and Aleksander Scibor Marchocki became the Castellan of Malogoski after Mikołaj. Franciszek Gajewski became the Castellan of Konarsk-Kuyavia and Florian Hrebnicki the Uniat Archbishop of Polotsk. Antoni Gajewski (d. 1775) was Castellan of Naklo, Lord of the regality of Łęczyca and of Kościany. His relative Rafał Tadeusz Gajewski (1714–76) became the Castellan of Rogozin. Józef Jakliński was then the Castellan of Kamensk/Spicymir 1759–1775.

At the end of the century, Józef Siemoński, the General adj. of King Poniatowski became supreme commander of Sandomierz uprising initiated by Kościuszko and Karol Podgorski escaped the Russian side by joining the Prussian army where he became General Major. Also in other parts of the Commonwealth the resistance against Poniatowski and Russia formed Confederations. Michał Władysław Lniski was vice Voivode and Marshal of the Confederation of Bar in Pomerania and Franciszek Ksawery Ścibor-Bogusławski was Rittmeister of same Confederation. Then Wojciech Marchocki was the Castellan of Sanok County and Józef Andrzej Mikorski the Castellan of Rawa County from 1791.

The Ostaszewski and the Blociszewski of Ostoja families hold many family members that were fighting against forces behind the partition of the Commonwealth. Of them, Tadeusz Błociszewski was General Major and Michał Ostaszewski (1720–1816) was one of main initiators of the Confederation of Bar in Subcarpathian Voivodeship. Tomasz Ostaszewski was helping the Confederation in his position as the Bishop of Plock. Finally, Antoni Baranowski of Ostoja was awarded and appointed as General Major of Royal Army by Tadeusz Kościuszko. Baranowski participated as the head of the division in the Battle of Maciejowice. Subsequently, remained off-duty, in 1812 he organized levée en masse in Lublin and Siedlce.

National resurgence

[edit]

19th century

[edit]It was the time of the boom for the nationalism and it was also the century of Adam Mickiewicz, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Frédéric Chopin and many others. By the 19th century the Commonwealth had ceased to exist, its territory having been partitioned between and occupied by Prussia, Russia and Austria. The local nobility rallied to fight this occupation and actively participated in the Napoleonic Wars. In addition to larger conflicts there were also over a hundred smaller military actions; Ostoja families participated in many of these, often serving as leaders.[114] rising up against the ruling authorities.[115]

Many Ostoja families were wealthy aristocrats[104] owning palaces, manor houses and large properties in Poland, Lithuania and throughout Europe. However, some Ostoja families, who participated these nationalistic uprisings and other military actions, were punished by having their properties confiscated. For example, according to Norman Davis, the consequences of the January Uprising in 1863 in the Russian part of the former Commonwealth included deportation of 80,000 people to Siberia and other working camps. Confiscated Ostoja properties were given over to those who were loyal to Russia, Austria or Prussia. In such way, several families gained in power during the partition, receiving high offices, nominations and lot of land. They were also given noble titles of Baron or Count or even Prince for their support and service. But Ostojas were not only good at fighting the enemy. Families kept part of their properties, manor houses and palaces outside the conflict and war to be able to support refugees, wounded and those in need. They acted both openly against foreign forces and in conspiracy using same successful tactics as families did in the time of Stibor of Stiboricz. Following information is taken from articles in Polish Wikipedia.

Adam Ostaszewki of Ostoja (1860–1934) was a pioneer of Polish aviation construction. He held a doctorate in philosophy and law. He was furthermore a writer, poet and translator of poetry from all over the world as he knew some 20 languages. He worked with astronomy, made sculptures, painted and was also interested in several different fields including optics, physics, electricity and magnetism, history, archaeology, chemistry, botany, and zoology. This remarkable man was often called "Leonardo from Wzdow".[116]

Kacper Kotkowski (1814–1875) was Catholic priest, head and commissar of the Sandomierz uprising[117] while Stanisław Błociszewski received the Order of Virtuti Militari for his patriotic fight as an officer against Russian forces.[118] Jan Czeczot was famous poet and ethnographer in Belarus. In Russia, Andrzej Miklaszewski was Actual State Councillor (e.g., Marshall and General - Table of Ranks) and in his position being able to help many families, saving them from exile in Siberia.[citation needed] In the meantime, Jan Kazimierz Ordyniec was owner and publisher of "Dziennik Warszawski" was heating up the resistance with articles. In the end, he was forced to emigrate and joined famous society at Hôtel Lambert in Paris.[119]

Spirydion Ostaszewski (1797–1875) was writing down Polish legends which was important for the cause and fight for the liberty of Poland. He participated in November Uprising 1830-1831 and helped many families returning from Siberia to settle down in west part of Ukraine. In the meantime, Teofil Wojciech Ostaszewski initiated first program against Serfdom. He was also the Marshal of Brzostowo County. Łukasz Solecki was Bishop of Przemyśl and professor of the Lviv University, Jan Aleksander Karłowicz became well known ethnographer, linguist, documenting the folklore while Mieczysław Karłowicz was composer of several symphonies and poems. Zygmunt Czechowicz was one of the initiators of the uprising in what is now Belarus.

Ladies Emma and Maria A. from Ostaszewski branch of Ostoja (1831–1912 and 1851–1918) were both devoted social activists and patriots. They raised funds for helping wounded and poor during the time of uprisings. Lady Karolina Wojnarowska (1814–1858) born Rylska was author writing under the pseudonym Karol Nowowiejski.

20th century to 1945

[edit]Several Ostoja families still owned castles and manor houses between the world wars.

From the end of the 18th century to the end of World War II, many Clan members served as military officers.[120] In the Second World War, some served in the Polish Army (Armia Krajowa), some of them left Russian Camps and Siberia to join the Anders Army, and others joined the British Royal Air Force.

Hipotit Brodowicz and Adam Mokrzecki reached the rank of General Major in the army, the later widely decorated for commanding troops in Polish–Soviet War between 1919 and 1921. Stefan Mokrzecki was also a general in the Polish army. Witold Ścibor-Rylski (1871–1926) was officer that emigrated to the US in 1898 but came back to Poland in 1914 to help the Country in World War I holding the rank of Colonel. He was serving Poland through the Polish-Soviet War and left for United States after the campaign. His service for Poland was widely recognized and he also finally received the rank of General from President August Zaleski.

Włodzimierz Zagórski (1882–1927) was a general in the Polish army. During the years of 1914–1916 he was a chief of staff of Polish Legions. Since November 1918 in Polish Armed Forces. As former intelligence officer, he accused Józef Piłsudski for being spy in favour of Austria. Outside the military service, Władysław Chotkowski (1843–1926) was a professor and head of Jagiellonian University and another Adam Ostaszewski was President of Plock until 1934.

Adam Hrebnicki-Doktorowicz (1857–1941) was a professor in agriculture development, founder of Institute in Ukraine and Karzimierz Zagórski (1883–1944) was widely recognized adventurer-pioneer, photographer.

Bronisław Bohatyrewicz (1870–1940) was a general in the Polish army, died in Katyn, general Kazimierz Suchcicki also died in Katyn 1940. General Zbigniew Ścibor Rylski (born 1917) succeeded to survive World War II and his wife, Zofia Rylska was during the war a master spy under the cover name of Marle Springer. Her information led to localization and destruction of the German battleship Tirpitz.

Stanislaw Danielewicz worked on breaking Enigma machine ciphers.

Karola Uniechowska(1904–1955) was voluntary medical doctor during World War II, she also participated in the Battle of Monte Cassino while Zofia Uniechowska (1909–1993) - achieved Order of Virtuti Militari for conspiracy against Nazi government in Poland. Stefan Ścibor-Bogusławski (1897–1978) was richly awarded colonel, also for his decisive actions in the Battle of Monte Cassino.

Stanisław Chrostowski (1897–1947) was a professor and artist.

Maxim Rylski (1895–1969) became a famous poet in Ukraine. There is a park and institution named after him in Kyiv, there are also three statues of him in this town in memory for his great contribution to the people of Ukraine.

Another Hrebnicki, Stanisław Doktorowicz-Hrebnicki (1888–1974), was a decorated professor in geology.

Wacław Krzywiec (1908–1956) was a famous warship komandor with the destroyer ORP Błyskawica. He was falsely accused by the communist regime in Poland after World War II, and was sent to prison after a famous trial, dying shortly after release.

The Słoński brothers served in the RAF as pilots and officers, all three dying in the course of duty.

Zbigniew Rylski, a major in the Polish army, was widely decorated for many important sabotage actions during World War II.

Zygmund Ignacy Rylski (1898–1945), legendary Major Hańcza, later advanced to the rank of colonel. He was one of the most devoted and widely decorated officers during World War II.

Lady Izabela Zielińska, born in Ostaszewska in 1910, had experience of 101 years of past changes and many wars. Being a musician, she was decorated with the medal of Gloria Artis in 2011. Marcelina Antonina Scibor-Kotkowska of Ostoja was the mother of Witold Gombrowicz.

Late 20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

After World War II, many Ostoja were treated as enemies of the state, and many chose exile, emigrating internationally. Some stayed in Poland, or returned from France, England, Scotland or where they had been placed on military service during WW II. With the exception of the Ostaszewski Palace in Kraków, communist governments in Poland, Lithuania (including what is now Belarus) and Ukraine confiscated all Ostoja property. After the fall of communism, none of these properties have been returned and no compensation has been given. Most of the old family properties were burned down by fighting armies during WW I, WW II and during Polish-Soviet War of 1919–1921. The existing Ostoya Palace around Rzeszow taken care by Rylski branch of Ostoja is an exception.

Antoni Uniechowski (1903–1976) was a widely recognized painter in Poland, known for his drawings. Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski (1928–1983) was a poet, writer and film director and Tadeusz Sędzimir (1894–1989) was worldwide known inventor. His name has been given to revolutionary methods of processing steel and metals used in every industrialized nation of the world. In 1990 Poland's large steel plant in Kraków (formerly the Lenin Steelworks) was renamed to Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks.

Joseph Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski (1922–1994) was famous artist that worked with photography, film-making, theater, design, fabric design, murals, kinetic and static sculpture, stained glass, vitreous enamel murals, op-collages, computer graphics and also laser art. He was a pioneer regarding laser kinetics and "sound and image".

Tadeusz Ostaszewski (1918–2003) was professor of fine arts in University of Kraków, Adam Kozłowiecki (1911–2007) was Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Lusaka in Zambia, Andrzej Zagórski (1926–2007) was devoted officer of Armia Krajowa that wrote over 250 publications about Polish underground resistance and Kazimierz Tumiłowicz (1932–2008) was creator of Siberian association of remembrance and social worker in Greater Poland. Andrzej Ostoja-Owsiany (1931–2008) was Senator in Poland after the fall of the communism. Błażej Ostoja Lniski is professor in fine arts at Warsaw Art Academy and Martin Ostoja Starzewski is professor in Mechanical Science & Engineering at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

In 2014, the Ostoja Clan Association was officially registered in Court with residence at Ostoya Palace in Jasionka, Rzeszów.

Notable members

[edit]

Notable members[121][122][123] of the Clan of Ostoja. Criteria used: published in Polish, German, Hungarian, Slovakian, Lithuanian Encyclopedia as well as in Ukraine and Belarus, listed in publications, articles and documentary films.

- Hanek Chełmski (c. 1390–1443) - comes, landlord and trusted man of King Jogaila

- Stibor of Stiboricz (1348–1414) - Lord of Upper Hungary, Voivode of Transylvania, Pressburg, Lord on 31 castles, one of richest and most powerful magnates in Europe

- Mikołaj Błociszewski - Castellan of Sanok 1403, Lord of Poznan 1417, one of the most trusted Lords of King Jogaila

- Jan de Jani - Voivode of Pomerania and Gdańsk 1454, Lord of regality of Tczew, Starogard Gdański, Nowe County and Kiszewskie

- Michael Sendivogius (1566–1636) - alchemist, philosopher, medical doctor

- Marcin Szyszkowski (1554–1630) - Bishop of Kraków, Prince of Siewierz

- Mikołaj Szyszkowski (1590–1643) - Prince-bishop of Warmia from 1633

- Krzysztof Boguszewski (d. 1635) - painter, artist of Greater Poland

- Aleksander Słuszka (1580–1647) - Castellan of Samogitia, Voivode of Minsk (d. 1638), Novogrod (d. 1642), Trakai (d. 1647)

- Paweł Ostoja Danielewicz, Judge of Vilnius 1648, Marshal of the Lithuanian Court of Justice, Lord of regality of Intursk

- Wincenty Danilewicz (born 1787 Minsk – died 23 March 1878 Jędrzejów), Chevau-léger in the Napoleonic campaign - awarded the French Order of Legion of Honour and Saint Helena Medal, chief archivist of heraldry administration of Congress Poland in Warsaw

- Kazimierz Siemienowicz (1600–1651) - General of Artillery

- Krystyna Ścibor-Bogusławska (-1783) - lady of regality of Wągłczew, nomination received by the King Poniatowski

- Antoni Baranowski (general) (1760–1821) – Major General

- Ignacy Ścibor Marchocki (1755–1827) - "Kingdom of Mińkowce"

- Jan Czeczot (1796–1847) - poet, ethnographer

- Mieczysław Karłowicz (1876–1909) – composer

- Stefan Mokrzecki (1862–1932) - general in the Russian and later Polish army

- Włodzimierz Zagórski (general) (1882–1927) - general

- Bronisław Bohatyrewicz (1870–1940) - general in the Polish army, murdered in Katyn

- Casimir Zagourski (1883–1944) - adventurer-pioneer

- Stanisław Ostoja-Chrostowski - painter and professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts

- Grażyna Chrostowska (1921-1942) - second lieutenant in Polish Army, intelligence service; poet

- Antoni Uniechowski (1903–1976)- painter

- Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski (1928–1983) - poet, writer and film director

- Tadeusz Sędzimir (1894–1989) - globally known inventor

- Joseph Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski (1922–1994) - artist

- Adam Kozłowiecki (1911–2007) - Cardinal and Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lusaka, Zambia

- Zbigniew Ścibor Rylski (1917–2018) - General, officer of Warsaw Uprising 1944

- Maria Szyszkowska (born 1937) - philosophy professor, senator

- Maja Ostaszewska (born 1972) - theater and film actress; Best Actress Award at the Polish Film Festival held in Gdynia in 1998

See also

[edit]- Ostoja coat of arms

- Stibor of Stiboricz

- Treaty of Lubowla

- Nobility in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Rulers of Transylvania

- List of castles in Slovakia

- Second Peace of Thorn

- Beckov Castle

- Malbork Castle

- Szlachta

- Union of Horodło

- Magnate

- Union of Lublin

- Sejm of the Republic of Poland

- Offices in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Polish Hussars

- Polish heraldry

- Polish clans

- Battle of Lwów (1918)

- November Uprising

- January Uprising

- Kościuszko Uprising

References

[edit]- ^ Prof. Józef Szymański, Herbarz rycerstwa polskiego z XVI wieku, Warsaw 2001, ISBN 83-7181-217-5

- ^ Klejnoty by Długosz, Armorial Gelre, Armorial Lyncenich, Codex Bergshammar, Armorial de Bellenville, Chronicle of Council of Constance, Toison d’Or

- ^ a b Franciszek Ksawery Piekosinski, Heraldyka polska wieków średnich (Polish Heraldry of the Middle Ages), Kraków, 1899

- ^ a b c d e Kaspar Niesiecki, Herbarz Polski, print Jan Bobrowicz, Leipzig 1839-1846

- ^ László: A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig - Életrajzi Lexikon (The High Officers of the Hungarian State from Saint Stephen to the Present Days - A Biographical Encyclopedia); Magyar Könyvklub, 2000, Budapest; ISBN 963-547-085-1

- ^ Bran Castle Museum official site, section about Dracula[1]

- ^ Dvořáková, Daniela, Rytier a jeho kráľ. Stibor zo Stiboríc a Žigmund Lucemburský. Budmerice, Vydavateľstvo Rak 2003, ISBN 978-80-85501-25-4

- ^ Magyar Arisztokracia-http://ferenczygen.tripod.com/

- ^ K. Tymieniecki, Procesy twórcze formowania się społeczeństwa polskiego w wiekach średnich (The Evolution of Polish Society in the Middle Ages), Warsaw, 1921.

- ^ http://www.poniec.pl – “Jak Chelmscy stali sie Ponieckimi”

- ^ IH PANhttp://www.slownik.ihpan.edu.pl/search.php?id=3775

- ^ a b c d e f Norman Davies. God's Playground. A History of Poland. Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795, Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present (1981 in English: Oxford: Oxford University Press.) Boże igrzysko. Historia Polski, t. I, Wydawnictwo ZNAK, Kraków 1987, ISBN 83-7006-052-8

- ^ Ignacy Krasicki - Satyry (Dziela, r.1802-1804), Ksiazka i Wiedza, Warsaw 1988

- ^ Piotr Nalecz-Malachowski, Zbior nazwisk szlachty, Lublin 1805, reprint Biblioteka narodowa w Warszawie 1985, (nr. sygn. List of ruleBN80204)

- ^ M. Cetwiński i M. Derwich, Herby, legendy, dawne mity, Wrocław 1987

- ^ a b K. Jasiński: Rodowód pierwszych Piastów, Poznań: 2004, pp. 185-187. ISBN 83-7063-409-5.

- ^ Legend about Jan z Jani - http://www.gniew.pl/index.php?strona=98&breakup=14

- ^ Helmut Nickel, Tamga and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols, The Metropolitan Art Museum 1973

- ^ a b Richard Brzezinski and Mariusz Mielczarek, The Sarmatians 600 BC-AD 450 (Men-At-Arms nr. 373), Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84176-485-6

- ^ Helmut Nickel, The Dawn of Chivalry, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Helmut Nickel, Tamga and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.

- ^ Karol Olejnik: Cedynia, Niemcza, Głogów, Krzyszków. Kraków: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1988. ISBN 83-03-02038-2.

- ^ http://www.artteka.pl/www/terra/pl/wysocice/wysocice.html Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine the Roman church in Wysocice

- ^ Norman Davies, Boże igrzysko, t. I, Wydawnictwo ZNAK, Kraków 1987, ISBN 83-7006-052-8, p. 128

- ^ Zygmunt Boras, Książęta piastowscy Wielkopolski, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań 1983, ISBN 83-210-0381-8

- ^ Bartosz Parpocki, Herby Rycerstwa Polskiego, Kraków 1584, Kazimierz Jozef Turowski edition, Kraków 1858, Nakladem Wydawnictwa Bibliteki Polskiej

- ^ Manteuffel, Tadeusz (1982). The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963-1194. Detroit, MICHIGAN: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1682-4. OCLC 7730959

- ^ Manteuffel, Tadeusz (1982). The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963-1194. Wayne State University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8143-1682-5

- ^ Oswald Balzer O., Genealogia Piastów, 2. wyd., Kraków 2005, ISBN 83-918497-0-8.

- ^ Oswald Balzer O., Genealogia Piastów, 2nd ed., Kraków 2005, ISBN 83-918497-0-8.

- ^ K. Tymieniecki, Procesy tworcze formowania sie spoleczenstwa polskiego w wiekach srednich, Warsaw 1921

- ^ Papricki, Bartosz (1858). Herby rycerstwa polskiego. Wydawnictwa Biblioteki Polskiej. p. 367.

- ^ Kaspar Niesiecki, Herbarz Polski, print Jan Bobrowicz, Leipzig 1839-1846

- ^ Minakowski (Boniecki), ISBN 83-918058-3-2

- ^ Andrzej Sarwa, Opowieść o Halinie, córce Piotra z Krępy, Armoryka edition

- ^ sandomierz.pl, oficialny servis miasta Sandomierza, historia, Sandomierskie legendy