History of Albany, New York (1664–1784)

| History of Albany, New York |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Albany, New York from 1664 to 1784 begins with the English takeover of New Netherland and ends with the ratification of the Treaty of Paris by the Congress of the Confederation in 1784, ending the Revolutionary War.

When New Netherland was captured by the English in 1664, the name Beverwijck was changed to Albany, in honor of the Duke of Albany (later James II of England and James VII of Scotland).[1][Note 1] Duke of Albany was a Scottish title given since 1398, generally to a younger son of the King of Scots.[2] The name is ultimately derived from Alba, the Gaelic name for Scotland.[3]

The Dutch briefly regained Albany in August 1673 and renamed the city Willemstadt; the English took permanent possession with the Treaty of Westminster (1674).[4] On November 1, 1683, the Province of New York was split into counties, with Albany County being the largest. At that time the county included all of present New York State north of Dutchess and Ulster Counties in addition to present-day Bennington County, Vermont, theoretically stretching west to the Pacific Ocean;[5][6] the city of Albany became the county seat.[7]

Albany was formally chartered as a municipality by provincial Governor Thomas Dongan on July 22, 1686. The Dongan Charter was virtually identical in content to the charter awarded to the city of New York three months earlier.[8] Dongan created Albany as a strip of land 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and 16 miles (26 km) long.[9] Over the years Albany would lose much of the land to the west and annex land to the north and south. At this point, Albany had a population of about 500 people.[10]

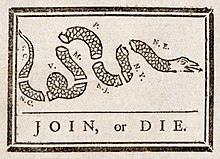

In 1754, representatives of seven British North American colonies met in the Stadt Huys, Albany's city hall, for the Albany Congress; Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania presented the Albany Plan of Union there, which was the first formal proposal to unite the colonies.[11] Although it was never adopted by Parliament, it was an important precursor to the United States Constitution.[12][Note 2] The same year, the French and Indian War, the fourth in a series of wars dating back to 1689, began; it ended in 1763 with French defeat, resolving a situation that had been a constant threat to Albany and held back its growth.[13]

In 1775, with the colonies in the midst of the Revolutionary War, the Stadt Huys became home to the Albany Committee of Correspondence (the political arm of the local revolutionary movement), which took over operation of Albany's government and eventually expanded its power to control all of Albany County. Tories and prisoners of war were often jailed in the Stadt Huys alongside common criminals.[14] In 1776, Albany native Philip Livingston signed the Declaration of Independence at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.[15]

During and after the Revolutionary War, Albany County saw a great increase in real estate transactions. After Horatio Gates' win over John Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777, the upper Hudson Valley was generally at peace as the war raged on elsewhere. Prosperity was soon seen all over Upstate New York. Migrants from Vermont and Connecticut began flowing in, noting the advantages of living on the Hudson and trading at Albany, while being only a few days' sail from New York City.[16] Albany reported a population of 3,498 in the first national census in 1790, an increase of almost 700% since its chartering.[10] In 1797, the state capital of New York was moved permanently to Albany. From statehood to this date, the Legislature had frequently moved the state capital between Albany, Kingston, Poughkeepsie, and the city of New York.[17] Albany is the second oldest state capital in the United States.[18]

1664–1744

In the period leading up to the Second Anglo-Dutch War, King Charles II of England granted the land from Maine to Delaware, which included all of New Netherland, to his brother James, Duke of York. In April 1664 four ships with a combined 450-men fighting force set sail for New Amsterdam. Fort Orange was surrendered to the English 16 days after New Amsterdam (the city of New York).[19] Surrender terms at New Amsterdam were quite generous.[20] Fort Orange was renamed Fort Albany, and the village of Beverswyck was renamed Albany, in honor of the Duke of York and Albany,[21] who later became King James II of England and James VII of Scotland. Captain John Manning was given command of Fort Albany.[19]

The Dutch briefly regained Albany in 1673, during which time the town was referred to as Willemstadt, but the Dutch again lost control in November 1674.[specify][21] Fort Albany was renamed Fort Nassau during this time. It was called Fort Nassau instead of Fort Orange to avoid confusion with New York City's renaming as New Orange.[22] After the English recapture of Willemstadt, all names were returned to their previous English names, but most Dutch political appointees from that period were retained. In 1676, Governor Edmund Andros of the Dominion of New England (of which the Province of New York was a part) had Fort Frederick built at the top of Yonkers Street, today the corner of State and Lodge streets, to replace Fort Albany, which was located by the Hudson River.[23]

Albany was formally chartered as a municipality by Governor Thomas Dongan on July 22, 1686. At this time Albany had a population of only 500. The "Dongan Charter" was virtually identical in content to the charter awarded to the city of New York three months earlier.[8] Pieter Schuyler was appointed first mayor of Albany the day the charter was signed.[24] As part of the Dongan Charter the city's boundaries were fixed with Patroon Street (today Clinton Avenue) as the northern limit and the "northern tip of Martin Gerritsen's Island" as the southern limit, both lines extending 16 miles (26 km) to the northwest. Albany was given the right to purchase 500 acres (2.0 km2) in "Schaahtecogue" (today Schaghticoke),[25][26] and 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) at "Tionnondoroge" (today Fort Hunter).[25][27]

In 1689 Albany became a center of resistance to Jacob Leisler who, during confusion over the Glorious Revolution, led Leisler's Rebellion and took de facto control over the colony. Leisler appointed a new mayor of Albany, but the replacement was not recognized by Schuyler or the other city fathers.[28] Three sloops sailed from the city of New York to Albany under the command of Jacob Milborne. Milborne attempted to enter Fort Albany and arrest Mayor Schuyler but was forced to return to New York after a group of Mohawks threatened to intervene on Schuyler's behalf.[29][clarification needed]

On February 8, 1690 the nearby settlement of Corlear (today Schenectady) was attacked by the French and their native allies. Over 60 people were killed, with more taken prisoner. Simon Schermerhorn rode all night to Albany to warn of the French incursion.[30] This incident (referred to as the Schenectady Massacre) is commemorated each year with a horse-ride by the mayor of Schenectady to Albany's city hall in addition to other local celebrations.[31]

In 1694 Johannes Abeel succeeded Schuyler to become the second mayor of Albany.[32] His term lasted only one year and in 1695 Evert Bancker was appointed Albany's third mayor.[why?][33]

Due to increased pirate activity in the Hudson River, one of the City Fathers, Robert Livingston, partnered with New York Governor Bellomont to destroy the pirate's bases in the West Indies. Captain William Kidd was hired to lead the expedition.[34]

In 1696, after only a year in office, Mayor Evert Bancker was replaced with Dirck Wesselse Ten Broeck who was then replaced two years later with Hendrick Hansen.[35] Hansen also served only one year and was replaced in 1699 by Pieter Van Brugh. Van Brugh and the succeeding three mayors (Jan Jansen Bleecker, Johannes Bleecker, Jr., Albert Janse Ryckman) each served only one year. Johannes Schuyler was appointed mayor in 1703 and was succeeded by David Schuyler in 1706. David Schuyler served only one year before he too was replaced. Evert Bancker, Albany's third mayor, was returned to office by the governor of New York in 1707 but then replaced in 1709 by Albany's second mayor, Johannes Abeel. Robert Livingston, Jr was appointed mayor in 1710 and became the first mayor since Pieter Schuyler to serve more than three years.[36] A census taken in 1710 showed the population had more than doubled since Albany became a city in 1686. The city had a population of 1,136; 113 of these were slaves.[37]

Queen Anne gave the Anglican community in Albany the right to build a church. After many years of conflict in which the city council was dominated by those of the Dutch Reformed faith who attempted to stop construction the church, Saint Peters was eventually built in 1717. It was the first Anglican church in New York west of the Hudson River. It is currently located in the middle of State Street at the intersection of Chapel Street.[38]

Robert Livingston was replaced as mayor by Myndert Schuyler in 1719, but Schuyler was replaced with former mayor Pieter Van Brugh the next year. The first recorded instance of a person from Ireland living in Albany occurred in 1720; 100 years later the Irish would become one of the most important immigrant groups in Albany history. In 1722 Albany was home to negotiations between the Iroquois and the provinces of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia resulting in the Treaty of Albany which limited the Iroquois to west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[39] Myndert Schuyler was returned to the office of mayor in 1723. In 1725 Schuyler was again replaced, this time with Johannes Cuyler, who was replaced a year later with Rutger Bleecker. In 1729 Bleecker was replaced with Johannes De Peyster, the only mayor to serve three non-consecutive terms. Johannes Hansen served for one year during 1731 after which De Peyster was returned to office by the governor. Also in 1731 Albany received from England its first primitive fire engine "to spout water" upon fires from a safer distance than using buckets carried up ladders.[40]

In 1733 De Peyster again was replaced, this time by Edward Holland. Holland, despite his last name, is the first mayor of Albany to be of any religion other than that of Dutch Reformed. He was of Anglican faith.[41] John Schuyler, Jr. was appointed mayor in 1740. He was of Dutch Reformed faith and served for one year before being replaced by De Peyster. De Peyster served his third and final time from 1741-1742. Cornelis Cuyler was appointed mayor in 1742.

1744−American Revolution

France and Britain declared war in 1744 and almost immediately forces were assembled in Albany for an invasion north to French Canada. French Canadian and natives attacked settlements north of Albany in 1745 and forced refugees to flee to Albany.[42] In response, Colonel William Johnson assembled representatives from the Iroquois Confederacy in Albany in 1746 and successfully convinced them to declare war against the French.[42] Also in 1746 Dirck Ten Broeck was appointed mayor by the governor. In 1748 peace came between France and Britain (and therefore between Canada and New York) through the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and Jacob Ten Eyck was appointed mayor.[43]

In 1750 Robert Sanders took the oath of office as mayor of Albany. In 1751 an auction was held to sell the rights to operate two ferries, one from Greenbush (today Rensselaer) to Albany, and another from Albany to Greenbush.[44] Also in 1751, a conference was held in Albany consisting of representatives from the Iroquois Nation, New York Governor George Clinton, the Indian commissioners from South Carolina, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and the Catawba tribe.[why?][44]

Since Massachusetts claimed a boundary extending "from sea to sea", which would include the city and much of the surrounding Albany County, disputes occurred between the sheriffs from Albany and the sheriffs from Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1751, after some Massachusetts officers were arrested and brought to Albany, the sheriff of Albany County was arrested and taken to Springfield.[specify][45]

Fear of imminent war with France led the British Lords of Trade in 1753 to send letters to the colonies of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, suggesting they meet in Albany to discuss their common defense. The next year all except Virginia and New Jersey attend, but Rhode Island and Connecticut attend in their stead.[45] Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania presented what is now known as the Albany Plan of Union. The meeting, which took place at the corner of Broadway and Hudson Avenue, became known as the Albany Congress. Although it was never adopted by Parliament, it was an important precursor to the United States Constitution. One month later, fears of a war with France came true and new stockades are erected at Albany.[46] Johannes Hansen is appointed mayor.

During the French and Indian War, Albany was the target of several French plans to cut the British colonies in half. Albany was also the point in which British and colonial troops were assembled, and where several invasions of French Canada, and specifically Montreal, were planned. By 1756, 10,000 soldiers were drilling in Albany in preparation of attacks on Canada or for defense of the route to Albany.[clarification needed][47] Sybrant Van Schaick was appointed mayor in 1756 and a smallpox epidemic occurred.[48] Refugees and soldiers continued to pour into the city as fighting along the routes to and from Canada escalated. Due to the large population of British soldiers, British tastes are introduced to Albany, and the first theatrical performance in the city occurred in the winter of 1757 by the British officers stationed there.[49]

General James Abercrombie's troops were stationed across the river from Albany in Greenbush, next to Fort Crailo. Dr. Shackburg of the British army composes "Yankee Doodle Dandy" as a mock of the various colonial militias that came to Albany.[50] In 1758 General Lord George Augustus Howe was killed at the Battle of Ticonderoga and was subsequently buried in Albany, today under the front vestibule of Saint Peter's Church on State Street. He is the only British Lord buried in the United States.[51][52] The Schuyler Mansion was built in 1761 by Colonel John Bradstreet for General Philip Schuyler, famous visitors in later years include George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Aaron Burr.[53]

Volkert Douw was appointed mayor in 1761. In 1763 a second fire engine was purchased. Prior to 1766 Albany had no permanent docks, so in that year the Common Council had three stone docks built. Each were 80 feet (24 m) long and between 30 feet (9.1 m) and 40 feet (12 m) wide.[54] In 1770 Abraham Cuyler was appointed mayor, being the last mayor to be appointed under a British Royal Commission.[55] Also in that year, a fourth dock was built along the river and the sloop Olive Branch became the first Albany ship to set sail for the West Indies.[56] Additionally, the city sold its remaining land in Schaghticoke. The Gazette became the first newspaper in Albany, first published in 1771 by Alexander and James Robertson.[57]

American Revolution

By 1774 events in other colonies regarding disputes with the British Parliament over taxation brought Albany into the wider issue of a colonial union for the first time since the Albany Congress. John Barclay became chairman of the newly formed Committee of Superintendence and Correspondence.[58] The committee selected Colonel Philip Schuyler, Abraham Yates Jr, Colonel Abraham Ten Broeck, Colonel Peter Livingston, and Walter Livingston as delegates from Albany (city and county) to the provincial congress in New York[specify] that would select the colony's delegates for the Philadelphia meeting of the Continental Congress. Of them, only Schuyler was selected to represent the colony at Philadelphia.[59] In 1775 the Continental Congress sent a committee to Albany to make a treaty with the Iroquois ensuring either their cooperation or their neutrality. It ended with no decision, but ultimately was a failure.

The last Dutch-born minister of the Dutch Reformed Protestant Church in Albany, Eilardus Westerlo, began preaching in English in 1782.

Despite the war, the mayor and several others celebrated the King's birthday in 1776, but were disrupted by a mob. Later that month the sign from the King's Arms Tavern at the corner of Green and Beaver is carried to State Street and burned.[60] Philip Livingston, born in Albany, signed the Declaration of Independence in July 1776 and on July 9 the New York Provincial Congress met at White Plains, officially changing the name from "Province of New York" to the "State of New York".[60] On July 19, the Declaration of Independence was read out loud in front of City Hall to a mass gathering. Due to the war, this was the first year city elections were not held.[61] City elections were not held in 1777 either.

The British copied French plans from the French and Indian War and sent General Burgoyne to Quebec in order to march on Albany and meet up with forces coming east from Niagara Falls and north from New York City, thereby cutting the New England states off from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Southern states.[62] The attacks from the west and south never actually got close to Albany, and Burgoyne's main thrust from the north was defeated at the Battle of Saratoga by General Gates. On October 17, 1777 Burgoyne surrendered his army to Gates, ending the immediate threat to Albany for the remainder of the war. Burgoyne was then sent to Albany where he lived at the Schuyler Mansion as a prisoner under house arrest.[63] To help protect Albany from further encroachment by British forces based in Manhattan, West Point was built along the Hudson between New York and Albany in 1778.

In 1778 the New York Legislature meeting in Poughkeepsie passed the "Act to remove all doubts concerning the corporation of the city of Albany", allowing the citizens to restructure the government. The legislature took over the job of appointing the mayor and subsequently appointed John Barclay. At that point, city elections resumed.[64] Barclay was Episcopalian and the first non-Dutch Reformed mayor since Edward Holland in 1733.[65] The next year General Abraham Ten Broeck was appointed to take over as mayor; he was of Dutch Reformed religion.

On January 27, 1780 the State Legislature met at Albany for the first time, meeting in City Hall on the corner of Broadway and Hudson Avenue.[66] The Legislature convenes again in Albany the next year.[citation needed]

In December of that year Alexander Hamilton married General Philip Schuyler's daughter Elizabeth at the Schuyler Mansion,".[67] which was Elizabeth's father's house and at the time called "The Pastures". Hamilton and his wife soon moved into a cottage on her father's land, where he studied law in the library of his father-in-law's house. Aaron Burr also studied law in that library, often getting into a tug-of-war over books with Hamilton.[68] In 1782 Burr also got married in Albany, at the Dutch Reformed Church the Schuylers attended.[69]

With Albany in relative calm after the Battle of Saratoga, not seriously threatened by native or British attacks, Albany could become more concentrated on commercial business, and in 1782 the first bank chartered in the city was created, the Bank of Albany. The American Revolutionary War came to an end in 1783 and Johannes Beekman was appointed mayor by the Governor.[why?] George Washington visited in this year and was presented with the "freedom of the city".[clarification needed][70]

Notes

- ^ James Stuart (1633–1701), brother and successor of Charles II, was both the Duke of York and Duke of Albany before being crowned James II of England and James VII of Scotland in 1685. His title of Duke of York is the source of the name of the province of New York.[1]

- ^ The Plan of Union's original intention was to unite the colonies in defense against aggressions of the French to the north; it was not an attempt to become independent from the auspices of the British crown.[12]

References

- ^ a b Brodhead (1874), p. 744

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (Albany, Dukes of). Encyclopædia Britannica Company; 1910. OCLC 197297659. p. 487.

- ^ In: E.G. Cody. The Historie of Scotland. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons; 1888. OCLC 3217086. p. 354.

- ^ Reynolds (1906), p. 72

- ^ Thorne, Kathryn Ford, Compiler & Long, John H., Editor: New York Atlas of Historical County Boundaries; The Newberry Library; 1993.

- ^ A Map of the Provinces of New-York and New-Yersey, with a Part of Pennsylvania and the Province of Quebec (Map). ca. 1:1,040,000. Cartography by Claude Joseph Sauthier. Matthew Albert Lotter. 1777 – via WikiMedia Commons.

- ^ French (1860), p. 155

- ^ a b New York State Museum. The Dongan Charter [Retrieved 2008-11-23]. Cite error: The named reference "Charter" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Reynolds (1906), pp. 84–85

- ^ a b New York State Museum. How a City Worked: Occupations in Colonial Albany [Retrieved 2009-01-10].

- ^ Rittner (2002), p. 22

- ^ a b McEneny (2006), p. 12

- ^ McEneny (2006), p. 56

- ^ New York State Museum. The Committee of Correspondence; 2010-03-08 [Retrieved 2010-08-19].

- ^ United States Congress. Livingston, Philip (1716–1778) [Retrieved 2009-10-09].

- ^ Anderson (1897), p. 68

- ^ The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Historical Publication Co; 1886. p. 24.

- ^ Rittner (2002), back cover

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 66. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "South Street Seaport". Fordham University. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ a b "Traders and Culture: Colonial Life in America" (PDF). Albany Institute of History and Art. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 72. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 76. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. xxvii. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 93. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "Schaghticoke". Colonial Albany Social History Project. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ "Fort Hunter". Colonial Albany Social History Project. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ "Jacob Leisler". Colonial Albany Social History Project. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 120. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 122. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Justin Mason. "Mayor re-creates historic ride". Schenectady Gazette. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Stefan Bielinski. "Johannes Abeel". Colonial Albany Social History Project. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 135. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 136. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 145. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 178. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 184. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 187. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "Treaties Defining the Boundaries Separating English and Native American Territories". Charles Grymes. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 206. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 218. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 231. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 236. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 245. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 246. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 248. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 216. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 251. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 253. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 254. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ "Albany Fun Facts". Albany County Convention and Visitor's Bureau. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ^ Don Rittner (2000). Images of America: Albany. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0088-7.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 256. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 263. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 267. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 269. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 270. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 271. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. pp. 272–3. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 284. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 286. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 289. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 340. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 341. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 344. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 351. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site at the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation web site.

- ^ Willard Randall (2003). Alexander Hamilton. HarperCollins. p. 252. ISBN 0-06-019549-5. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Ron Chernow. Alexander Hamilton. Penguin. p. 169. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ Cuyler Reynolds (1906). Albany Chronicles. p. 361. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

Further reading

- Roberts, Warren. A Place in History: Albany in the Age of Revolution, 1775–1825. SUNY Press; 2010. ISBN 978-1-4384-3329-5.