History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses

Ideas concerning the origin and fate of the world date from the earliest known writings; however, for almost all of that time, there was no attempt to link such theories to the existence of a "Solar System", simply because almost no one knew or believed that the Solar System, in the sense we now understand it, existed. The first step towards a theory of Solar System formation was the general acceptance of heliocentrism, the model which placed the Sun at the centre of the system and the Earth in orbit around it. This conception had been gestating for thousands of years, but was only widely accepted by the end of the 17th century. The first recorded use of the term "Solar System" dates from 1704.[1]

Currently accepted hypotheses

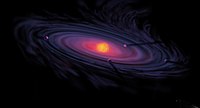

The most widely accepted theory of planetary formation, known as the nebular hypothesis, maintains that 4.6 billion years ago, the Solar System formed from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud which was light years across. Several stars, including the Sun, formed within the collapsing cloud. The gas that formed the Solar System was slightly more massive than the Sun itself. Most of the mass collected in the centre, forming the Sun; the rest of the mass flattened into a protoplanetary disc, out of which the planets and other bodies in the Solar System formed.

Just as the Sun and planets were born, so they will eventually die. As the Sun begins to age, it will cool and bloat outward to many times its current diameter, becoming a red giant, before casting off its outer layers (forming what is misleadingly called a planetary nebula) and becoming a stellar corpse known as a white dwarf. The planets will follow the Sun's course; some will be destroyed, others will be ejected into interstellar space, but ultimately, given enough time, the Sun's retinue will eventually disappear.

Formation hypotheses

The nebular hypothesis was first proposed in 1734 by Emanuel Swedenborg[2] and later elaborated and expanded upon by Immanuel Kant in 1755. A similar theory was independently formulated by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796.[3]

In 1749, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon conceived the idea that that the planets were formed when a comet collided with the Sun, sending matter out to form the planets. However, Laplace refuted this idea in 1796, showing that any planets formed in such a way would eventually crash into the Sun. Laplace felt that the near-circular orbits of the planets were a necessary consequence of their formation.[4] Today, comets are known to be far too small to have created the Solar System in this way.[4]

In 1755, Immanuel Kant speculated that observed nebulae may in fact be regions of star and planet formation. In 1796, Laplace elaborated by arguing that the nebula collapsed into a star, and, as it did so, the remaining material gradually spun outward into a flat disc, which then formed the planets.[4]

Alternative theories

The nebular hypothesis initially faced the obstacle of angular momentum; if the Sun had indeed formed from the collapse of such a cloud, the planets should be orbiting around it far more slowly. The Sun, though it contains almost 99.9 percent of the system's mass, contains just 1 percent of its angular momentum.[5]

Attempts to resolve the angular momentum problem led to the temporary abandonment of the nebular hypothesis in favour of a return to "two-body" theories.[4] For several decades, many astronomers preferred the tidal or near-collision hypothesis put forward by James Jeans in 1917, in which the planets were considered to have been formed due to the approach of some other star to the Sun. This near-miss would have drawn large amounts of matter out of the Sun and the other star by their mutual tidal forces, which could have then condensed into planets.[4] However, in 1929 astronomer Harold Jeffreys countered that such a near-collision was massively unlikely.[4] Objections to the hypothesis were also raised by the American astronomer Henry Norris Russell, who showed that it ran into problems with angular momentum for the outer planets, with the planets struggling to avoid being reabsorbed by the Sun.[6]

In 1944, the Soviet astronomer Otto Schmidt proposed that the Sun, in its present form, passed through a dense interstellar cloud, emerging enveloped in a cloud of dust and gas, from which the planets eventually formed. This solved the angular momentum problem by assuming that the Sun's slow rotation was peculiar to it, and that the planets did not form at the same time as the Sun.[4] However, this hypothesis was severely dented by Victor Safronov who showed that the amount of time required to form the planets from such a diffuse envelope would far exceed the Solar System's determined age.[4]

In 1960, W. H. McCrea proposed the protoplanet theory, in which the Sun and planets individually coalesced from matter within the same cloud, with the smaller planets later captured by the Sun's larger gravity.[4] This theory has a number of issues, such as explaining the fact that the planets all orbit the Sun in the same direction, which would appear highly unlikely if they were each individually captured.[4]

The capture theory, proposed by M. M. Woolfson in 1964, posits that the Solar System formed from tidal interactions between the Sun and a low-density protostar. The Sun's gravity would have drawn material from the diffuse atmosphere of the protostar, which would then have collapsed to form the planets.[7] However, the capture theory predicts a different age for the Sun than for the planets,[citation needed] whereas the similar ages of the Sun and the rest of the Solar System indicate that they formed at roughly the same time.[8]

Reemergence of the nebular hypothesis

In 1978, astronomer A. J. R. Prentice revived the Laplacian nebular model in his Modern Laplacian Theory by suggesting that the angular momentum problem could be resolved by drag created by dust grains in the original disc which slowed down the rotation in the centre.[4][9] Prentice also suggested that the young Sun transferred some angular momentum to the protoplanetary disc and planetesimals through supersonic ejections understood to occur in T Tauri stars.[4][10] However, his contention that such formation would occur in toruses or rings has been questioned, as any such rings would disperse before collapsing into planets.[4]

The birth of the modern widely accepted theory of planetary formation—the Solar Nebular Disk Model (SNDM)—can be traced to the works of Soviet astronomer Victor Safronov.[11] His book Evolution of the protoplanetary cloud and formation of the Earth and the planets,[12] which was translated to English in 1972, had a long-lasting effect on the way scientists thought about the formation of the planets.[13] In this book almost all major problems of the planetary formation process were formulated and some of them solved. Safronov's ideas were further developed in the works of George Wetherill, who discovered runaway accretion.[4] By the early 1980s, the nebular hypothesis in the form of SNDM had come back into favour, led by two major discoveries in astronomy. First, a number of apparently young stars, such as Beta Pictoris, were found to be surrounded by discs of cool dust, much as was predicted by the nebular hypothesis. Second, the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, launched in 1983, observed that many stars had an excess of infrared radiation that could be explained if they were orbited by discs of cooler material.

Outstanding issues

While the broad picture of the nebular hypothesis is widely accepted,[14] many of the details are not well understood and continue to be refined.

The refined nebular model was developed entirely on the basis of observations of our own Solar System because it was the only one known until the mid 1990s. It was not confidently assumed to be widely applicable to other planetary systems, although scientists were anxious to test the nebular model by finding of protoplanetary discs or even planets around other stars.[15] As of March 2008, the discovery of nearly 280 extrasolar planets[16] has turned up many surprises, and the nebular model must be revised to account for these discovered planetary systems, or new models considered.

Among the extrasolar planets discovered to date are planets the size of Jupiter or larger but possessing very short orbital periods of only a few days. Such planets would have to orbit very closely to their stars; so closely that their atmospheres would be gradually stripped away by solar radiation.[17][18] There is no consensus on how to explain these so-called hot Jupiters, but one leading idea is that of planetary migration, similar to the process which is thought to have moved Uranus and Neptune to their current, distant orbit. Possible processes that cause the migration include orbital friction while the protoplanetary disc is still full of hydrogen and helium gas[19] and exchange of angular momentum between giant planets and the particles in the protoplanetary disc.[20][21][22]

The detailed features of the planets are another problem. The solar nebula hypothesis predicts that all planets will form exactly in the ecliptic plane. Instead, the orbits of the classical planets have various (but small) inclinations with respect to the ecliptic. Furthermore, for the gas giants it is predicted that their rotations and moon systems will also not be inclined with respect to the ecliptic plane. However most gas giants have substantial axial tilts with respect to the ecliptic, with Uranus having a 98° tilt.[23] The Moon being relatively large with respect to the Earth and other moons which are in irregular orbits with respect to their planet is yet another issue. It is now believed these observations are explained by events which happened after the initial formation of the Solar System.[24] For instance, the large axial tilts of many planets may be explained by giant impacts with massive planetesimals early in the Solar System's evolution.[25]

Solar evolution hypotheses

Attempts to isolate the physical source of the Sun's energy, and thus determine when and how it might ultimately run out, began in the 19th century. At that time, the prevailing scientific view on the source of the Sun's heat was that it was generated by gravitational contraction. In the 1840s, astronomers J. R. Mayer and J. J. Waterson first proposed that the Sun's massive weight causes it to collapse in on itself, generating heat, an idea expounded upon in 1854 by both Hermann von Helmholtz and Lord Kelvin, who further elaborated on the idea by suggesting that heat may also be produced by the impact of meteors onto the Sun's surface.[26] However, the Sun only has enough gravitational potential energy to power its luminosity by this mechanism for about 30 million years—far less than the age of the Earth. (This collapse time is known as the Kelvin-Helmholtz timescale.)[27]

Albert Einstein's development of the theory of relativity in 1905 led to the understanding that nuclear reactions could create new elements from smaller precursors, with the loss of energy. In his treatise Stars and Atoms, Arthur Eddington suggested that pressures and temperatures within stars were great enough for hydrogen nucei to fuse into helium; a process which could produce the massive amounts of energy required to power the Sun.[26] In 1935, Eddington went further and suggested that other elements might also form within stars.[28] Spectral evidence collected after 1945 showed that the distribution of the commonest chemical elements, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, neon, iron etc., was fairly uniform across the galaxy. This suggested that these elements had a common origin.[28] A number of anomalies in the proportions hinted at an underlying mechanism for creation. Lead is heavier than gold, but far more common. Hydrogen and helium (elements 1 and 2) are virtually ubiquitous yet lithium and beryllium (elements 3 and 4) are extremely rare.[28]

Red giants

While the unusual spectra of red giant stars had been known since the 19th century,[29] it was George Gamow who, in the 1940s, first understood that they were stars of roughly solar mass that had run out of hydrogen in their cores and had resorted to burning the hydrogen in their outer shells.[citation needed] This allowed Martin Schwarzschild to drew the connection between red giants and the finite lifespans of stars. It is now understood that red giants are stars in the last stages of their life cycles.

Fred Hoyle noted that, even while the distribution of elements was fairly uniform, different stars had varying amounts of each element. To Hoyle, this indicated that they must have originated within the stars themselves. The abundance of elements peaked around the atomic number for iron, an element that could only have been formed under intense pressures and temperatures. Hoyle concluded that iron must have formed within giant stars.[28] From this, in 1945 and 1946, Hoyle constructed the final stages of a star's life cycle. As the star dies, it collapses under its own weight, leading to a stratified chain of fusion reactions: carbon-12 fuses with helium to form oxygen-16; oxygen-16 fuses with helium to produce neon-20, and so on up to iron.[30] There was, however, no known method by which carbon-12 could be produced. Isotopes of beryllium produced via fusion were too unstable to form carbon, and for three helium atoms to form carbon-12 was so unlikely as to have been impossible over the age of the universe. However, in 1952 the physicist Ed Salpeter showed that a short enough time existed between the formation and the decay of the beryllium isotope that another helium had a small chance to form carbon, but only if their combined mass/energy amounts were equal to that of carbon-12. Hoyle, employing the anthropic principle, showed that it must be so, since he himself was made of carbon, and he existed. When the matter/energy level of carbon-12 was finally determined, it was found to be within a few percent of Hoyle's prediction.[31]

White dwarfs

The first white dwarf discovered was in the triple star system of 40 Eridani, which contains the relatively bright main sequence star 40 Eridani A, orbited at a distance by the closer binary system of the white dwarf 40 Eridani B and the main sequence red dwarf 40 Eridani C. The pair 40 Eridani B/C was discovered by Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel on January 31, 1783;[32], p. 73 it was again observed by Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve in 1825 and by Otto Wilhelm von Struve in 1851.[33][34] In 1910, it was discovered by Henry Norris Russell, Edward Charles Pickering and Williamina Fleming that despite being a dim star, 40 Eridani B was of spectral type A, or white.[35]

White dwarfs were found to be extremely dense soon after their discovery. If a star is in a binary system, as is the case for Sirius B and 40 Eridani B, it is possible to estimate its mass from observations of the binary orbit. This was done for Sirius B by 1910,[36] yielding a mass estimate of 0.94 solar mass. (A more modern estimate is 1.00 solar mass.)[37] Since hotter bodies radiate more than colder ones, a star's surface brightness can be estimated from its effective surface temperature, and hence from its spectrum. If the star's distance is known, its overall luminosity can also be estimated. Comparison of the two figures yields the star's radius. Reasoning of this sort led to the realization, puzzling to astronomers at the time, that Sirius B and 40 Eridani B must be very dense. For example, when Ernst Öpik estimated the density of a number of visual binary stars in 1916, he found that 40 Eridani B had a density of over 25,000 times the Sun's, which was so high that he called it "impossible".[38]

Such densities are possible because white dwarf material is not composed of atoms bound by chemical bonds, but rather consists of a plasma of unbound nuclei and electrons. There is therefore no obstacle to placing nuclei closer to each other than electron orbitals—the regions occupied by electrons bound to an atom—would normally allow.[39] Eddington, however, wondered what would happen when this plasma cooled and the energy which kept the atoms ionized was no longer present.[40] This paradox was resolved by R. H. Fowler in 1926 by an application of the newly devised quantum mechanics. Since electrons obey the Pauli exclusion principle, no two electrons can occupy the same state, and they must obey Fermi-Dirac statistics, also introduced in 1926 to determine the statistical distribution of particles which satisfy the Pauli exclusion principle.[41] At zero temperature, therefore, electrons could not all occupy the lowest-energy, or ground, state; some of them had to occupy higher-energy states, forming a band of lowest-available energy states, the Fermi sea. This state of the electrons, called degenerate, meant that a white dwarf could cool to zero temperature and still possess high energy.

Planetary nebulae

Planetary nebulae are generally faint objects, and none are visible to the naked eye. The first planetary nebula discovered was the Dumbbell Nebula in the constellation of Vulpecula, observed by Charles Messier in 1764 and listed as M27 in his catalogue of nebulous objects. To early observers with low-resolution telescopes, M27 and subsequently discovered planetary nebulae somewhat resembled the gas giants, and William Herschel, discoverer of Uranus, eventually coined the term 'planetary nebula' for them, although, as we now know, they are very different from planets.

The central stars of planetary nebulae are very hot. Their luminosity, though, is very low, implying that they must be very small. Only once a star has exhausted all its nuclear fuel can it collapse to such a small size, and so planetary nebulae came to be understood as a final stage of stellar evolution. Spectroscopic observations show that all planetary nebulae are expanding, and so the idea arose that planetary nebulae were caused by a star's outer layers being thrown into space at the end of its life.

Lunar origins hypotheses

Over the centuries, many scientific hypotheses have been advanced concerning the origin of Earth's Moon. One of the earliest was the so-called binary accretion model, which concluded that the Moon accreted from material in orbit around the Earth left over from its formation. Another, the fission model, was developed by George Darwin, (son of Charles Darwin) who noted that, as the Moon is gradually receding from the Earth at a rate of about 4 cm per year, so at one point in the distant past it must have been part of the Earth, but was flung outward by the momentum of Earth's then–much faster rotation. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that the Moon's density, while less than Earth's, is about equal to that of Earth's rocky mantle, suggesting that, unlike the Earth, it lacks a dense iron core. A third hypothesis, known as the capture model, suggested that the Moon was an independently orbiting body that had been snared into orbit by Earth's gravity.[42]

Apollo missions

However, these hypotheses were all refuted by the Apollo lunar missions, which introduced a stream of new scientific evidence; specifically concerning the Moon's composition, its age, and its history. These lines of evidence contradict many predictions made by these earlier models.[42] The rocks brought back from the Moon showed a marked decrease in water relative to rocks elsewhere in the Solar System, and also evidence of an ocean of magma early in its history, indicating that its formation must have produced a great deal of energy. Also, oxygen isotopes in lunar rocks showed a marked similarity to those on Earth, suggesting that they formed at a similar location in the solar nebula. The capture model fails to explain the similarity in these isotopes (if the Moon had originated in another part of the Solar System, those isotopes would have been different), while the co-accretion model cannot adequately explain the loss of water (if the Moon formed in a similar fashion to the Earth, the amount of water trapped in its mineral structure would also be roughly similar). Conversely, the fission model, while it can account for the similarity in chemical composition and the lack of iron in the Moon, cannot adequately explain its high orbital inclination and, in particular, the large amount of angular momentum in the Earth/Moon system, more than any other planet–satellite pair in the Solar System.[42]

Giant impact hypothesis

For many years after Apollo, the binary accretion model was settled on as the best hypothesis for explaining the Moon's origins, even though it was known to be flawed. Then, at a conference in Kona, Hawaii in 1984, a compromise model was composed that accounted for all of the observed discrepancies. Originally formulated by two independent research groups in 1976, the giant impact model supposed that a massive planetary object, the size of Mars, had collided with Earth early in its history. The impact would have melted Earth's crust, and the other planet's heavy core would have sunk inward and merged with Earth's. The superheated vapour produced by the impact would have risen into orbit around the planet, coalescing into the Moon. This explained the lack of water (the vapour cloud was too hot for water to condense), the similarity in composition (since the Moon had formed from part of the Earth), the lower density (since the Moon had formed from the Earth's crust and mantle, rather than its core), and the Moon's unusual orbit (since an oblique strike would have imparted a massive amount of angular momentum to the Earth/Moon system.[42]

Outstanding issues

However, the giant impact model has been criticised for being too explanatory; it can be expanded to explain any future discoveries and as such, makes no predictions. Also, many claim that much of the material from the impactor would have ended up in the Moon, meaning that the isotope levels would be different, but they are not. Also, while some volatile compounds such as water are absent from the Moon's crust, many others, such as manganese, are not.[42]

Other natural satellites

While the co-accretion and capture models are not currently accepted as valid explanations for the existence of the Moon, they have been employed to explain the formation of other natural satellites in the Solar System. Jupiter's Galilean satellites are believed to have formed via co-accretion,[43] while the Solar System's irregular satellites, such as Triton, are all believed to have been captured.[44]

References

- ^ ""Solar"". etymoline. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ Swedenborg, Emanuel. 1734, (Principia) Latin: Opera Philosophica et Mineralia (English: Philosophical and Mineralogical Works), (Principia, Volume 1)

- ^ See, T. J. J. (1909). "The Past History of the Earth as Inferred from the Mode of Formation of the Solar System". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 48: 119. Retrieved 2006-07-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n M. M. Woolfson (1993). "The Solar System: Its Origin and Evolution". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 34: 1–20. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Woolfson, M. M. (1984). "Rotation in the Solar System". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 313: 5. doi:10.1098/rsta.1984.0078.

- ^ Benjamin Crowell (1998–2006). "5". Conservation Laws. lightandmatter.com.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ J. R. Dormand & M. M. Woolfson (1971). "The capture theory and planetary condensation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 151: 307. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Weidenschilling, S. J.; Spaute, D.; Davis, D. R.; Marzari, F.; Ohtsuki, K. (1997). "Accretional Evolution of a Planetesimal Swarm". Icarus. 128: 429–455. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5747. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prentice, A. J. R. (1978). "Origin of the solar system. I - Gravitational contraction of the turbulent protosun and the shedding of a concentric system of gaseous Laplacian rings". Moon and Planets. 19: 341–398. doi:10.1007/BF00898829.

- ^ Ferreira, J.; Dougados, C.; Cabrit, S. (2006). "Which jet launching mechanism(s) in T Tauri stars?". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 453: 785. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20054231. arXiv:astro-ph/0604053.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nigel Henbest (1991). "Birth of the planets: The Earth and its fellow planets may be survivors from a time when planets ricocheted around the Sun like ball bearings on a pinball table". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ Safronov, Viktor Sergeevich (1972). Evolution of the Protoplanetary Cloud and Formation of the Earth and the Planets. Israel Program for

Scientific Translations. ISBN 0706512251.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 19 (help) - ^ George W. Wetherill (1989). "Leonard Medal Citation for Victor Sergeevich Safronov". Meteoritics. 24: 347.

- ^ e. g.

- Kokubo, Eiichiro (2002). "Formation of Protoplanet Systems and Diversity of Planetary Systems". Astrophysical Journal. 581: 666. doi:10.1086/344105.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lissauer, J. J. (2006). "Planet Formation, Protoplanetary Disks and Debris Disks". In L. Armus and W. T. Reach, eds. (ed.). The Spitzer Space Telescope: New Views of the Cosmos. Vol. 357. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. p. 31.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - Zeilik, Michael A.; Gregory, Stephan A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0030062284.

- Kokubo, Eiichiro (2002). "Formation of Protoplanet Systems and Diversity of Planetary Systems". Astrophysical Journal. 581: 666. doi:10.1086/344105.

- ^ "Planet Quest, Terrestrial Planet Finder". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Jean Schneider. "The extrasolar planets encyclopedia". Paris University. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Weaver, D.; Villard, R. (2007-01-31). "Hubble Probes Layer-cake Structure of Alien World's Atmosphere". University of Arizona, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (Press Release). Retrieved 2007-08-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ballester, Gilda E. (2007). "The signature of hot hydrogen in the atmosphere of the extrasolar planet HD 209458b". Nature. 445 (7127): 511. doi:10.1038/nature05525. PMID 17268463.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Benjamin Crowell (2008). "Vibrations and Waves". Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Tsiganis, K.; Gomes, R.; Morbidelli, A.; Levison, H. F. (2005). "Origin of the orbital architecture of the giant planets of the Solar System". Nature. 435 (7041): 459. doi:10.1038/nature03539. PMID 15917800.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lissauer, J. J. (2006). "Planet Formation, Protoplanetary Disks and Debris Disks". In L. Armus and W. T. Reach (ed.). The Spitzer Space Telescope: New Views of the Cosmos. Vol. 357. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. p. 31.

- ^ ">Fogg, M. J. (2007). "On the formation of terrestrial planets in hot-Jupiter systems". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 461: 1195. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066171. arXiv:astro-ph/0610314.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Heidi B. Hammel (2006). "Uranus nears Equinox" (PDF). Pasadena Workshop. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Frank Crary (1998). "The Origin of the Solar System". Colorado University, Boulder. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Adrián Brunini (2006). "Origin of the obliquities of the giant planets in mutual interactions in the early Solar System". Nature. 440 (7088): 1163–1165. doi:10.1038/nature04577. PMID 16641989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b David Whitehouse (2005). The Sun: A Biography. John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Carl J. Hansen, Steven D. Kawaler, and Virginia Trimble (2004). Stellar interiors: physical principles, structure, and evolution. New York: Springer. p. 4. ISBN 0-387-20089-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Simon Mitton (2005). "Origin of the Chemical Elements". Fred Hoyle: A Life in Science. Aurum. pp. 197–222.

- ^ Oscar Straniero, Roberto Gallino, and Sergio Cristallo (17 October 2006). "s process in low-mass asymptotic giant branch stars". Nuclear Physics A. 777: 311–339. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.01.011. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Faulkner (2003). "Fred Hoyle, Red Giants and beyond". Astrophysics and Space Science. 285 (2): 339–339. doi:10.1023/A:1025432324828. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ The Nuclear Physics Group. "Life, Bent Chains, and the Anthropic Principle". The University of Birmingham. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ Catalogue of Double Stars, William Herschel, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 75 (1785), pp. 40–126

- ^ The orbit and the masses of 40 Eridani BC, W. H. van den Bos, Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands 3, #98 (July 8, 1926), pp. 128–132.

- ^ Astrometric study of four visual binaries, W. D. Heintz, Astronomical Journal 79, #7 (July 1974), pp. 819–825.

- ^ How Degenerate Stars Came to be Known as White Dwarfs, J. B. Holberg, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 37 (December 2005), p. 1503.

- ^ Preliminary General Catalogue, L. Boss, Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution, 1910.

- ^ The Age and Progenitor Mass of Sirius B, James Liebert, Patrick A. Young, David Arnett, J. B. Holberg, and Kurtis A. Williams, The Astrophysical Journal 630, #1 (September 2005), pp. L69–L72.

- ^ The Densities of Visual Binary Stars, E. Öpik, The Astrophysical Journal 44 (December 1916), pp. 292–302.

- ^ On the relation between the masses and luminosities of the stars, A. S. Eddington, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 84 (March 1924), pp. 308–332.

- ^ On Dense Matter, R. H. Fowler, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 87 (1926), pp. 114–122.

- ^ The Development of the Quantum Mechanical Electron Theory of Metals: 1900-28, Lillian H. Hoddeson and G. Baym, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 371, #1744 (June 10, 1980), pp. 8–23.

- ^ a b c d e Paul D. Spudis (1996). "Whence the Moon?". The Once and Future Moon. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 157–169.

- ^ Robin M. Canup and William R. Ward (2002). "Formation of the Galilean Satellites: Conditions of Accretion". The Astronomical Journal. 124: 3404–3423. doi:10.1086/344684. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ^ David Nesvorný, David Vokrouhlický and Alessandro Morbidelli (2007). "Capture of Irregular Satellites during Planetary Encounters". The Astronomical Journal. 133: 1962–1976. doi:10.1086/512850. Retrieved 2008-04-22.