History of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (1917–1927)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The "History of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union" reflects a period of change for both Russia and the world. Though the terms "Soviet Russia" and "Soviet Union" are synonymous in everyday vocabulary, when we talk about the foundations of the Soviet Union, "Soviet Russia" refers to the few years after the abdication of the crown of the Russian Empire by Tsar Nicholas II (in 1917), but before the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922. Early in its conception, the Soviet Union strived to achieve harmony among all peoples of all countries. The original ideology of the state was primarily based on the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In its essence, Marx's theory stated that economic and political systems went through an inevitable evolution in form, by which the current capitalist system would be replaced by a socialist state before achieving international cooperation and peace in a "Workers' Paradise," creating a system directed by what Marx called "Pure Communism."

Displeased by the relatively few changes made by the Tsar after the Revolution of 1905, Russia became a hotbed of anarchism, socialism and other radical political systems. The dominant socialist party, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), subscribed to Marxist ideology. Starting in 1903, a series of splits in the party between two main leaders was escalating: the Bolsheviks (meaning "majority") led by Vladimir Lenin, and the Mensheviks (meaning "minority") led by Julius Martov. Up until 1912, both groups continued to stay united under the name "RSDLP," but significant and irreconcilable differences between Lenin and Martov led the party to eventually split. A struggle for political dominance subsequently began between the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks. Not only did these groups fight with each other, but they also had common enemies, notably, those trying to bring the Tsar back to power. Following the February Revolution in 1917, the Mensheviks gained control of Russia and established a provisional government, but this lasted only until the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution (also called the Bolshevik Revolution) later in the year. To distinguish themselves from other socialist parties, the Bolshevik party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (RCP).

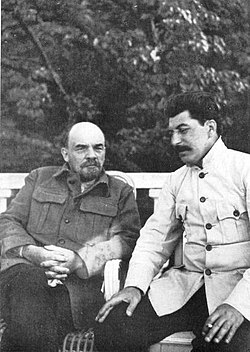

Under the control of the party, all politics and attitudes that were not strictly RCP were suppressed, under the premise that the RCP represented the proletariat and all activities contrary to the party's beliefs were "counterrevolutionary" or "anti-socialist." During the years between 1917 and 1923, the Soviet Union achieved peace with the Central Powers, their enemies in World War I, but also fought the Russian Civil War against the White Army and foreign armies from the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, among others. This resulted in large territorial changes, albeit temporarily for some of these. Eventually crushing all opponents, the RCP spread Soviet style rule quickly and established itself through all of Russia. Following Lenin's death in 1924, Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the RCP, became Lenin's successor and continued as leader of the Soviet Union until the 1950s.

The Russian Revolution of 1917

During World War I, Tsarist Russia experienced famine and economic collapse. The demoralized Russian Army suffered severe military setbacks, and many soldiers deserted the front lines. Dissatisfaction with the monarchy and its policy of continuing the war grew among the Russian people. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne following the February Revolution of 1917 (N.S. March. See: Soviet calendar.), causing widespread rioting in Petrograd and other major Russian cities. The Russian Provisional Government was installed immediately following the fall of the Tsar by the Provisional Committee of the State Duma in early March 1917 and received conditional support of the Mensheviks. Led first by Prince Georgy Lvov, then Alexander Kerensky the Provisional Government consisted mainly of the parliamentarians most recently elected to the State Duma of the Russian Empire, which had been overthrown alongside Tsar Nicholas II. The new Provisional Government maintained its commitment to the war, joining the Triple Entente which the Bolsheviks opposed. The Provisional Government also postponed the land reforms demanded by the Bolsheviks.

Lenin, embodying the Bolshevik ideology, viewed alliance with the capitalist countries of Western Europe and the United Stsates as involuntary servitude of the proletariat, who was forced to fight the imperialists' war. As seen by Lenin, Russia was reverting to the rule of the Tsar, and it was the job of Marxist revolutionaries, who truly represented socialism and the proletariat, to oppose such counter-socialistic ideas and support socialist revolutions in other countries. Within the military, mutiny and desertion were pervasive among conscripts, though being AWOL (Absent Without Leave) was not uncommon throughout all ranks. The intelligentsia was dissatisfied over the slow pace of social reforms; poverty was worsening, income disparities and inequality were becoming out of control while the Provisional Government grew increasingly autocratic and inefficient. The government appeared to be on the verge of succumbing to a military junta. Deserting soldiers returned to the cities and gave their weapons to angry, and extremely hostile, socialist factory workers. The deplorable and inhumane poverty and starvation of major Russian centers produced optimum conditions for revolutionaries.

During the months between February and October 1917, the power of the Provisional Government was consistently questioned by nearly all political parties. A system of 'dual power' emerged, in which the Provisional Government held nominal power, though increasingly opposed by the Petrograd Soviet, their chief adversary, controlled by the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (both democratic socialist parties politically to the right of the Bolsheviks). The Soviet chose not to force further changes in government due to the belief that the February Revolution was Russia's "crowing" overthrow of the bourgeois. The Soviet also believed that the new Provisional Government would be tasked with implementing democratic reforms and pave the way for a proletarian revolution. Though the creation of a government not based on the dictatorship of the proletariat in any form, was viewed as a "retrograde step" in Vladmir Lenin's April Theses. However, the Provisional Government still remained an overwhelmingly powerful governing body.

Failed military offensives in summer 1917 and large scale protesting and riots in major Russian cities (as advocated by Lenin in his Theses, known as the July Days) led to the deployment of troops in late August to restore order. The July Days were suppressed and blamed on the Bolsheviks, forcing Lenin into hiding. Still, rather than use force, many of the deployed soldiers and military personnel joined the rioters, disgracing the government and military at-large. It was during this time that support for the Bolsheviks grew and another of its leading figures, Leon Trotsky, was elected chair of the Petrograd Soviet, which had complete control over the defenses of the city, mainly, the city's military force. On October 24, in early days of the October Revolution, the Provisional Government moved against the Bolsheviks, arresting activists and destroying pro-Communist propaganda. The Bolsheviks were able to portray this as an attack against the People's Soviet and garnered support for the Red Guard of Petrograd to take over the Provisional Government. The adminstative offices and government buildings were taken with little opposition or bloodshed. The generally accepted end of this transitional revolutionary period, which will lead to the creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) lies with the assault and capture of the poorly defended Winter Palace (the traditional home and symbol of power of the Tsar) on the evening of October 26, 1917.

The Mensheviks and the right-wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries, outraged by the abusive and coercive acts carried out by the Red Guard and Bolsheviks, fled Petrograd, leaving control in the hands of the Bolsheviks and remaining Left Socialist Revolutionaries. On October 25, 1917, the Sovnarkom was established by the Russian Constitution of 1918 as the administrative arm of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. By January 6, 1918, the VTsIK, supported by the Bolsheviks, ratified the dissolution of the Russian Constituent Assembly, which intended to establish the non-Bolshevik Russian Democratic Federative Republic as the permanent form of government established at its Petrograd session held January 5 and January 6, 1918.

The Russian Civil War

Prior to the revolution, the Bolshevik doctrine of democratic centralism argued that only a tightly knit and secretive organization could successfully overthrow the government; after the revolution, they argued that only such an organization could prevail against foreign and domestic enemies. Fighting the civil war would actually force the party to put these principles into practice.

Arguing that the revolution needed not a mere parliamentary organization but a party of action which would function as a scientific body of direction, a vanguard of activists, and a central control organ, the Tenth Party Congress banned factions within the party, initially intending it only to be a temporary measure after the shock of the Kronstadt rebellion. It was also argued that the party should be an elite body of professional revolutionaries dedicating their lives to the cause and carrying out their decisions with iron discipline, thus moving toward putting loyal party activists in charge of new and old political institutions, army units, factories, hospitals, universities, and food suppliers. Against this backdrop, the nomenklatura system would evolve and become standard practice.

In theory, this system was to be democratic since all leading party organs would be elected from below, but also centralized since lower bodies would be accountable to higher organizations. In practice, "democratic centralism" was centralist, with decisions of higher organs binding on lower ones, and the composition of lower bodies largely determined by the members of higher ones. Over time, party cadres would grow increasingly careerist and professional. Party membership required exams, special courses, special camps, schools, and nominations by three existing members.

In December 1917, the Cheka was founded as the Bolshevik's first internal security force following the failed assassination attempt on Lenin's life. Later it changed names to GPU, OGPU, MVD, NKVD and finally KGB.

The Polish–Soviet War

The frontiers between Poland, which had established an unstable independent government following World War I, and the former Tsarist empire, were rendered chaotic by the repercussions of the Russian revolutions, the civil war and the winding down World War I. Poland's Józef Piłsudski envisioned a new federation (Międzymorze), forming a Polish-led East European bloc to form a bulwark against Russia and Germany, while the Russian SFSR considered carrying the revolution westward by force. When Piłsudski carried out a military thrust into Ukraine in 1920, he was met by a Red Army offensive that drove into Polish territory almost to Warsaw. However, Piłsudski halted the Soviet advance at the Battle of Warsaw and resumed the offensive. The "Peace of Riga" signed in early 1921 split the territory of Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Soviet Russia.

Creation of the USSR

On December 29, 1922 a conference of plenipotentiary delegations from the Russian SFSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR approved the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR and the Declaration of the Creation of the USSR, forming the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. These two documents were confirmed by the 1st Congress of Soviets of the USSR and signed by heads of delegations[1] - Mikhail Kalinin, Mikhail Tskhakaya, Mikhail Frunze and Grigory Petrovsky, Alexander Chervyakov[2] respectively on December 30, 1922.

The New Economic Policy

During the Civil War (1917–21), the Bolsheviks adopted War communism, which entailed the breakup of the landed estates and the forcible seizure of agricultural surpluses. In the cities there were intense food shortages and a breakdown in the money system (at the time many Bolsheviks argued that ending money's role as a transmitter of "value" was a sign of the rapidly approaching communist epoch). Many city dwellers fled to the countryside - often to tend the land that the Bolshevik breakup of the landed estates had transferred to the peasants. Even small scale "capitalist" production was suppressed.

The Kronstadt rebellion signaled the growing unpopularity of War Communism in the countryside: in March 1921, at the end of the civil war, disillusioned sailors, primarily peasants who initially had been stalwart supporters of the Bolsheviks under the provisional government, revolted against the new regime. Although the Red Army, commanded by Trotsky, crossed the ice over the frozen Baltic Sea to quickly crush the rebellion, this sign of growing discontent forced the party to foster a broad alliance of the working class and peasantry (80% of the population), despite left factions of the party which favored a regime solely representative of the interests of the revolutionary proletariat. At the Tenth Party Congress, it was decided to end War Communism and institute the New Economic Policy (NEP), in which the state allowed a limited market to exist. Small private businesses were allowed and restrictions on political activity were somewhat eased.

However, the key shift involved the status of agricultural surpluses. Rather than simply requisitioning agricultural surpluses in order to feed the urban population (the hallmark of War Communism), the NEP allowed peasants to sell their surplus yields on the open market. Meanwhile, the state still maintained state ownership of what Lenin deemed the "commanding heights" of the economy: heavy industry such as the coal, iron, and metallurgical sectors along with the banking and financial components of the economy. The "commanding heights" employed the majority of the workers in the urban areas. Under the NEP, such state industries would be largely free to make their own economic decisions.

In the cities and between the cities and the countryside, the NEP period saw a huge expansion of trade in the hands of full-time merchants - who were typically denounced as "speculators" by the leftists and also often resented by the public. The growth in trade, though, did generally coincide with rising living standards in both the city and the countryside (around 80% of Soviet citizens were in the countryside at this point).

The Soviet NEP (1921–29) was essentially a period of "market socialism" similar to the economic reform in China in 1978 in that both foresaw a role for private entrepreneurs and limited markets based on trade and pricing rather than fully centralized planning. As an interesting aside, during the first meeting in the early 1980s between Deng Xiaoping and Armand Hammer, a U.S. industrialist and prominent investor in Lenin's Soviet Union, Deng pressed Hammer for as much information on the NEP as possible.

During the NEP period, agricultural yields not only recovered to the levels attained before the Bolshevik Revolution, but greatly improved. The break-up of the quasi-feudal landed estates of the Tsarist-era countryside gave peasants their greatest incentives ever to maximize production. Now able to sell their surpluses on the open market, peasant spending gave a boost to the manufacturing sectors in the urban areas. As a result of the NEP, and the break-up of the landed estates while the Communist Party was strengthening power between 1917–1921, the Soviet Union became the world's greatest producer of grain.

Agriculture, however, would recover from civil war more rapidly than heavy industry. Factories, badly damaged by civil war and capital depreciation, were far less productive. In addition, the organization of enterprises into trusts or syndicates representing one particular sector of the economy would contribute to imbalances between supply and demand associated with monopolies. Due to the lack of incentives brought by market competition, and with little or no state controls on their internal policies, trusts were likely to sell their products at higher prices.

The slower recovery of industry would pose some problems for the peasantry, who accounted for 80% of the population. Since agriculture was relatively more productive, relative price indexes for industrial goods were higher than those of agricultural products. The outcome of this was what Trotsky deemed the "Scissors Crisis" because of the scissors-like shape of the graph representing shifts in relative price indexes. Simply put, peasants would have to produce more grain to purchase consumer goods from the urban areas. As a result, some peasants withheld agricultural surpluses in anticipation of higher prices, thus contributing to mild shortages in the cities. This, of course, is speculative market behavior, which was frowned upon by many Communist Party cadres, who considered it to be exploitative of urban consumers.

In the meantime, the party took constructive steps to offset the crisis, attempting to bring down prices for manufactured goods and stabilize inflation, by imposing price controls on essential industrial goods and breaking-up the trusts in order to increase economic efficiency.

The death of Lenin and the fate of the NEP

Following Lenin's third stroke, a troika made up of Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev emerged to take day to day leadership of the party and the country and try to block Trotsky from taking power. Lenin, however, had become increasingly anxious about Stalin and, following his December 1922 stroke, dictated a letter (known as Lenin's Testament) to the party criticizing him and urging his removal as general secretary, a position which was starting to arise as the most powerful in the party. Stalin was aware of Lenin's Testament and acted to keep Lenin in isolation for health reasons and increase his control over the party apparatus.

Zinoviev and Bukharin became concerned about Stalin's increasing power and proposed that the Orgburo which Stalin headed be abolished and that Zinoviev and Trotsky be added to the party secretariat thus diminishing Stalin's role as general secretary. Stalin reacted furiously and the Orgburo was retained but Bukharin, Trotsky and Zinoviev were added to the body.

Due to growing political differences with Trotsky and his Left Opposition in the fall of 1923, the troika of Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev reunited. At the Twelfth Party Congress in 1923, Trotsky failed to use Lenin's Testament as a tool against Stalin for fear of endangering the stability of the party.

Lenin died in January 1924 and in May his Testament was read aloud at the Central Committee but Zinoviev and Kamenev argued that Lenin's objections had proven groundless and that Stalin should remain General Secretary. The Central Committee decided not to publish the testament.

Meanwhile, the campaign against Trotsky intensified and he was removed from the position of People's Commissar of War before the end of the year. In 1925, Trotsky was denounced for his essay Lessons of October, which criticized Zinoviev and Kamenev for initially opposing Lenin's plans for an insurrection in 1917. Trotsky was also denounced for his theory of permanent revolution which contradicted Stalin's position that socialism could be built in one country, Russia, without a worldwide revolution. As the prospects for a revolution in Europe, particularly Germany, became increasingly dim through the 1920s, Trotsky's theoretical position began to look increasingly pessimistic as far as the success of Russian socialism was concerned.

With the resignation of Trotsky as War Commissar, the unity of the troika began to unravel. Zinoviev and Kamenev again began to fear Stalin's power and felt that their positions were threatened. Stalin moved to form an alliance with Bukharin and his allies on the right of the party who supported the New Economic Policy and encouraged a slowdown in industrialization efforts and a move towards encouraging the peasants to increase production via market incentives. Zinoviev and Kamenev criticized this policy as a return to capitalism. The conflict erupted at the Fourteenth Party Congress held in December 1925 with Zinoviev and Kamenev now protesting against the dictatorial policies of Stalin and trying to revive the issue of Lenin's Testament which they had previously buried. Stalin now used Trotsky's previous criticisms of Zinoviev and Kamenev to defeat and demote them and bring in allies like Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov and Mikhail Kalinin. Trotsky was dropped from the politburo entirely in 1926. The Fourteenth Congress also saw the first developments of the Stalin's cult of personality with him being referred to as "leader" for the first time and becoming the subject of effusive praise from delegates.

Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev formed a United Opposition against the policies of Stalin and Bukharin, but they had lost influence as a result of the inner party disputes and in October 1927, Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev were expelled from the Central Committee. In November, prior to the Fifteenth Party Congress, Trotsky and Zinoviev were expelled from the Communist Party itself as Stalin sought to deny the Opposition any opportunity to make their struggle public. By the time, the Congress finally convened in December 1927. Zinoviev had capitulated to Stalin and denounced his previous adherence to the opposition as "anti-Leninist" and the few remaining members still loyal to the opposition were subjected to insults and humiliations. By early 1928, Trotsky and other leading members of the Left Opposition had been sentenced to internal exile.

Stalin now moved against Bukharin by appropriating Trotsky's criticisms of his right wing policies and he promoted a new general line of the party favoring collectivization of the peasantry and rapid industrialization of industry, forcing Bukharin and his supporters into a Right Opposition.

At the Central Committee meeting held in July 1928, Bukharin and his supporters argued that Stalin's new policies would cause a breach with the peasantry. Bukharin also alluded to Lenin's Testament. While he had support from the party organization in Moscow and the leadership of several commissariats, Stalin's control of the secretariat was decisive in that it allowed Stalin to manipulate elections to party posts throughout the country, giving him control over a large section of the Central Committee. The Right Opposition was defeated and Bukharin attempted to form an alliance with Kamenev and Zinoviev but it was too late.

See also

- History of Russia

- Timeline of Russian history

- Historiography in the Soviet Union

- Leninism

- Politics of the Soviet Union

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

References

Further reading

- Acton, Edward, V. I͡U Cherni͡aev, and William G. Rosenberg, eds. Critical companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921 (Indiana University Press, 1997), emphasis on historiography

- Cohen, Stephen F. Rethinking the Soviet Experience: Politics and History since 1917. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Daniels, Robert V. "The Soviet Union in Post‐Soviet Perspective" Journal of Modern History (2002) 74#2 pp: 381-391. in JSTOR

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Russian Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982, 208 pages. ISBN 0-19-280204-6

- Hosking, Geoffrey. The First Socialist Society: A History of the Soviet Union from Within (2nd ed. Harvard UP 1992) 570pp

- Gregory, Paul R. and Robert C. Stuart, Russian and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure (7th ed. 2001)

- Kort, Michael. The Soviet Colossus: History and Aftermath (7th ed. 2010) 502pp

- Kotkin, Stephen. Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928 (2014)*Lincoln, W. Bruce. Passage Through Armageddon: The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914-1918 (1986)

- Lewin, Moshe. Russian Peasants and Soviet Power. (Northwestern University Press, 1968)

- McCauley, Martin. The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union (2007), 522 pages.

- Moss, Walter G. A History of Russia. Vol. 2: Since 1855. 2d ed. Anthem Press, 2005.

- Nove, Alec. An Economic History of the USSR, 1917–1991. 3rd ed. London: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-14-015774-3.

- Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996)

- Remington, Thomas. Building Socialism in Bolshevik Russia. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984.

- Service, Robert. A History of Twentieth-Century Russia. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-674-40348-7.

- Service, Robert, Lenin: A Biography (2000)

- Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography (2004), along with Tucker the standard biography

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin as Revolutionary, 1879-1929 (1973); Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1929-1941. (1990) online edition with Service, a standard biography; online at ACLS e-books