History of crossbows

This history of crossbows documents the historical development and use of the crossbow.

It is not clear exactly where and when the crossbow originated, however it is believed to have been invented in Europe and China around 6th to 5th Century BCE. The current archaeological evidence points to the common usage of crossbows in China for military purposes during the Warring States period from at the very latest, the second half of the 4th century BCE onwards.

China and South East Asia

The earliest evidence of crossbows (Chinese: 弩; pinyin: nǔ) in ancient China and neighboring peoples dates back to at least the 6th century BC. According to Sir Joseph Needham in his Science and Civilisation in China, it is not possible to pinpoint exactly which of the East Asian peoples invented the crossbow. Linguistically, it derives from non-Chinese languages of China's then neighbors, who were often hired as marksmen mercenaries, while the first records and examples of representations as well as specimens are from China. However, there is unquestionable evidence that the crossbow was used for military purposes at least as far back as the Warring States period from the second half of the 4th century BC onwards.[1]

In terms of archaeological evidence, bronze crossbow bolts dating from as early as the mid-5th century BCE have been found at a Chu burial site in Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei Province.[2] The earliest handheld crossbow stocks with a bronze trigger, dating from the 6th century BCE, were found in Tombs 3 and 12 at Qufu, Shandong, previously the capital of Lu.[3][4] Other early finds of crossbows were discovered in Tomb 138 at Saobatang, Hunan Province and dated to the mid-4th century BCE.[5][6]

Repeating crossbows, first mentioned in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, were discovered in 1986 in Tomb 47 at Qinjiazui, Hubei Province, and were dated to around the 4th century BCE.[7] The earliest Chinese documents mentioning a crossbow were texts from the 4th to 3rd centuries BC attributed to the followers of Mozi. This source refers to the use of a giant crossbow catapult between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, corresponding to the late Spring and Autumn Period. Sun Tzu's influential book The Art of War (first appearance dated between 500 BCE to 300 BCE[8]) refers to the characteristics and use of crossbows in chapters 5 and 12 respectively.[9] One of the earliest reliable descriptions of this weapon in warfare is of an ambush which took place at the Battle of Maling in 341 BCE. Crossbow remains have also been found amongst the soldiers of the Terracotta Army near the mausoleum of China's first emperor Qin Shi Huang (260-210 BCE).[10]

The repeating crossbow and multiple bow arcuballista were both developed in China.[11] When discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the nomadic Xiongnu and Han dynasty armies in a memorandum to the throne in 169 BCE, official Chao Cuo deemed the crossbow and repeating crossbow of the Han armies superior to the Xiongnu bow, even though the latter were trained to shoot behind themselves while riding.[12] According to one authority, the crossbow had become "nothing less than the standard weapon of the Han armies," by the second century BCE.[13]

Throughout the southeastern Asia the crossbow is still used by primitive and tribal peoples both for hunting and war, from the Assamese mountains through Burma, Siam and to the confines of Indo-China. The peoples of the northeastern Asia possess it also, both as weapon and toy, but use it mainly in the form of unattended traps; this is true of the Yakut, Tungus, and Chukchi, even of the Ainu in the east. There seems to be no way of answering the question whether it first arose among the barbaric forefathers of these Asian peoples before the rise of the Chinese culture in their midst, and then underwent its technical development only therein, or whether it spread outwards from China to all the environing peoples. The former seems the more probable hypothesis, given the further linguistic evidence in its support.[14]

In Vietnamse historical legend, the ruler and general Thục Phán who ruled over the ancient kingdom of Âu Lạc from 257 to 207 BCE is said to have owed his power to a magic crossbow, capable of shooting thousands of arrows at once.

Crossbow technology was transferred from the Chinese to Champa, which Champa used in its invasion of the Khmer Empire's Angkor in 1177.

According to the Chinese Wujing Zongyao military manuscript of 1044, the crossbow used en masse was the most effective weapon against northern nomadic cavalry charges.[15] Elite crossbowmen were also valued as long-range snipers as was the case when the Liao Dynasty general Xiao Talin was picked off by a Song crossbowman at the Battle of Shanzhou in 1004.[15] Crossbows were mass-produced in state armories with designs improving as time went on, such as the use of a mulberry wood stocks and brass; a crossbow in 1068 could pierce a tree at 140 paces.[16]

-

Chinese Chuangzi Nu stationary windlass device with triple-bow arcuballista

-

Chinese repeating crossbow with pull lever and automatic reload magazine

-

Chinese Lian Nu (連弩), multiple shot crossbow without a visible nut or cocking aid

Europe

The earliest evidence for the crossbow in Europe dates back to the 5th century BCE when the gastraphetes, an ancient Greek crossbow type, appeared. The device was described by the Greek author Heron of Alexandria in his work Belopoeica ("On Catapult-making"), which draws on an earlier account of his famous compatriot engineer Ctesibius (fl. 285–222 BCE). Heron identifies the gastraphetes as the forerunner of the later catapult, which places its invention some unknown time prior to 420 BCE.[17]

The gastraphetes was a large artillery crossbow mounted on a heavy stock with a lower and upper section, the lower being the case fixed to the bow and the upper being the slider which had the same dimensions as the case.[18] Meaning "belly-bow",[18] it was called as such because the concave withdrawal rest at one end of the stock was placed against the stomach of the operator, which he could press to withdraw the slider before attaching a string to the trigger and loading the bolt; this could thus store more energy than regular Greek bows.[19] It was used in the Siege of Motya in 397 BCE. This was a key Carthaginian stronghold in Sicily, as described in the 1st century AD by Heron of Alexandria in his book Belopoeica.[20] Alexander's siege of Tyre in 332 BCE provides reliable sources for the use of these weapons by the Greek besiegers.[21]

The efficiency of the gastraphetes was improved by introducing the ballista. Its application in sieges and against rigid infantry formations featured more and more powerful projectiles, leading to technical improvements and larger ballistae. The smaller sniper version was often called Scorpio.[22] An example for the importance of ballistae in Hellenistic warfare is the Helepolis, a siege tower employed by Demetrius during the Siege of Rhodes in 305 BCE. At each level of the moveable tower were several ballistae. The large ballistae at the bottom level were designed to destroy the parapet and clear it of any hostile troop concentrations while the small armorbreaking scorpios at the top level sniped at the besieged. This suppressive shooting would allow them to mount the wall with ladders more safely.[23]

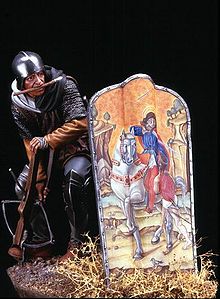

According to R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, in 36 BCE a Han empire expedition into central Asia encountered and defeated a contingent of Roman legionaries. The Romans were suggested to have been part of Antony's campaign against Parthia. Chinese victory was based on their crossbows, whose bolts and darts seem to "have penetrated Roman shields and armor." The theory is that the Chinese crossbow was transmitted to the Roman world through this encounter.[24] The use of crossbows in Medieval warfare dates back to Roman times and is again evident from the battle of Hastings (1066) until about 1525 AD.[25] They almost completely superseded hand bows in many European armies (England being a rare exception) in the twelfth century for a number of reasons. Although a longbow had greater range and penetration, and could achieve comparable accuracy and faster shooting rate than a wooden or composite crossbow, the latter can be used effectively after a week of training, while a comparable single-shot skill with a longbow could take years of practice. Later crossbows (sometimes referred to as arbalests), utilizing all-steel prods were able later made with power close (and sometime superior) to longbows, but were more expensive to produce and slower to reload because they required the aid of mechanical devices such as the cranequin or windlass to draw back their extremely heavy bows. Usually these could only shoot 2 bolts per minute vs 12 or more with a skilled archer, - often necessitating the use of a pavise to protect the operator from enemy fire.[26] In the armies of Europe,[27] mounted and unmounted crossbowmen, often mixed with slingers, javeliners and archers, occupied a central position in battle formations. Usually they engaged the enemy in offensive skirmishes before an assault of mounted knights. Crossbowmen were also valuable in counterattacks to protect their infantry. Crossbowmen were held in high esteem as professional soldiers, often commanding higher rates of pay than other footsoldiers.[28] The rank of commanding officer of the crossbowmen corps was one of the highest positions in many medieval armies, including those of Spain, France and Italy. Crossbowmen were held in such high regard in Spain that they were granted status on par with the knightly class.[25] Along with polearm weapons made from farming equipment, the crossbow was also a weapon of choice for insurgent peasants such as the Taborites. Genoese crossbowmen were famous mercenaries hired throughout medieval Europe, while the crossbow also played an important role in anti-personnel defense of ships.[29]

Crossbowmen among the Flemish citizens,[27] in the army of Richard Lionheart, and others, could have up to two servants, two crossbows and a pavise to protect the men. Then one of the servants had the task of reloading the weapons, while the second subordinate would carry and hold the pavise (the archer himself also wore protective armor). Such a three-man team could shoot 8 shots per minute, compared to a single crossbowman's 3 shots per minute. The archer was the leader of the team, the one who owned the equipment, and the one who received payment for their services. The payment for a crossbow mercenary was higher than for a longbow mercenary, but the longbowman did not have to pay a team of assistants and his equipment was cheaper. Thus the crossbow team was twelve percent less efficient than the longbowman since three of the latter could be part of the army in place of one team. Furthermore, the prod and bow string of a composite crossbow were subject to damage in rain whereas the longbowman could simply unstring his bow to protect the string. The composite crossbow was shown to be an inferior weapon at Crécy in 1346, at Poitiers in 1356 and at Agincourt in 1415 where the French armies paid dearly for their reliance upon it. As a result, use of the crossbow declined sharply in France,[26] and the French authorities made attempts to train longbowmen of their own. After the conclusion of the Hundred Years' War, however, the French largely abandoned the use of the longbow, and consequently the military crossbow saw a resurgence in popularity. The crossbow continue to see use in French armies by both infantry and mounted troops until as late as 1520 when, as with elsewhere in continental Europe, the crossbow would be largely eclipsed by the handgun. Spanish forces in the New World would make extensive use of the crossbow, even after it had largely fallen out of use in Europe, with crossbowmen participating in Hernán Cortés' conquest of Mexico and accompanying Francisco Pizarro on his initial expedition to Peru - though by the time of the conquest of Peru in 1532-1523 he would have only a dozen such men remaining in his service.[25]

Mounted knights armed with lances proved ineffective against formations of pikemen combined with crossbowmen whose weapons could penetrate most knights' armor. The invention of pushlever and ratchet drawing mechanisms enabled the use of crossbows on horseback, leading to the development of new cavalry tactics. Knights and mercenaries deployed in triangular formations, with the most heavily armored knights at the front. Some of these riders would carry small, powerful all-metal crossbows of their own. Crossbows were eventually replaced in warfare by gunpowder weapons, although early guns had slower rates of fire and much worse accuracy than contemporary crossbows. Later, similar competing tactics would feature harquebusiers or musketeers in formation with pikemen, pitted against cavalry firing pistols or carbines.

Up until the seventeenth century most beekeepers in Europe kept their hives spread across the woods and had to defend them against bears. Therefore their guild was granted the right to bear arms and is commonly depicted carrying heavy crossbows.

While the military crossbow had largely been supplanted by firearms on the battlefield by 1525, the sporting crossbow in various forms remained a popular hunting weapon in Europe until the eighteenth century.[30]

A bomb-throwing crossbow called the Sauterelle was used by the French and British armies on the Western Front during World War I. It could throw an F1 grenade or Mills bomb 110–140 m (120–150 yd).[31]

Islamic World

The Saracens called the crossbow qaws Ferengi, or "Frankish bow", as the Crusaders used the crossbow against the Arab and Turkoman horsemen with remarkable success. The adapted crossbow was used by the Islamic armies in defence of their castles. Later footstrapped version become very popular among the Muslim armies in Iberia. During the Crusades, Europeans were exposed to Saracen composite bows, made from layers of different material—often wood, horn and sinew—glued together and bound with animal tendon. These composite bows could be made smaller and handier than wooden self-bows while retaining the pull, and were adopted for crossbow prods across Europe. Crossbow prods could be more easily waterproofed than hand bows, which was essential in the humid European climate.

Africa and in the Americas

In Central Africa simple crossbows were used for hunting and as a scout weapon, previously thought to have been first introduced by the Portuguese. Until recently they were especially in use by different tribes of the pygmy-people, usually with poisoned and relatively small arrows. This silent technique of hunting in the tropical forest is quite similar to that of the South American indigenous hunting method with blow pipe and poisoned arrows. It makes sure not to startle up the prey, for example if a first shot goes astray. Since the small arrow is rarely deadly itself, the animal will drop from the trees after some time because of the poisoning. In the American South, the crossbow was used by the conquistadors for hunting and warfare when firearms or gunpowder were unavailable because of economic hardships or isolation.[29] Light hunting crossbows were traditionally used by the Inuit in Northern America.

Use of crossbows today

Crossbows are mostly used for target shooting in modern archery. In some countries they are still used for hunting, such as in most of states within the USA, parts of Asia, Europe, Australia and Africa. In modern Wild Care uses with special projectiles are in whale research to take blubber biopsy samples without harming the whales or other marine big "game" .[32]

Modern military and paramilitary usage

The crossbow is still used in modern times by various militaries,[33][34][35][36] tribal forces[37] and in China even by the police forces.[38] As their worldwide distribution is not restricted by regulations on arms, they are used as silent weapons and for their psychological effect,[39] even reportedly using poisoned projectiles.[40] Crossbows are used for ambush and anti-sniper[41] operations or in conjunction with ropes to establish zip-lines in difficult terrain.[42]

See also

References

- ^ Needham, Joseph (2004), Science and Civilisation in China, Vol 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press, p. 135, ISBN 0-521-08732-5

- ^ Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China: Second Impression, With Corrections. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09632-9. pp. 153, 157–158.

- ^ You (1994), 80.

- ^ A Crossbow Mechanism with Some Unique Features from Shandong, China. Asian Traditional Archery Research Network. Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ^ Mao (1998), 109–110.

- ^ Wright (2001), 159.

- ^ Lin (1993), 36.

- ^ James Clavell, The Art of War, prelude

- ^ https://www.gutenberg.org/files/132/132.txt

- ^ Weapons of the terracotta army

- ^ "A look at crossbows in China".

- ^ Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77064-5. Page 203.

- ^ Graff 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol 5 Part 6. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-521-08732-5.

- ^ a b Peers, 130.

- ^ Peers, 130–131.

- ^ Campbell 2003, pp. 3ff.; Schellenberg 2006, pp. 18f.

- ^ a b DeVries, Kelly Robert. (2003). Medieval Military Technology. Petersborough: Broadview Press. ISBN 0-921149-74-3. Page 127.

- ^ DeVries, Kelly Robert. (2003). Medieval Military Technology. Petersborough: Broadview Press. ISBN 0-921149-74-3. Page 128.

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, Sarah B. Pomeroy, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts (1999). Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509742-4, p. 366

- ^ John Warry, Warfare in the Classical World, p. 79

- ^ Duncan B Campbell, Ancient Siege Warfare 2005 Osprey Publishing ISBN 1-84176-770-0, p. 26-56

- ^ John Warry, Warfare in the Classical World, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2794-5, p.90

- ^ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present, Fourth Edition (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993), 133, apparently relying on Homer H. Dubs, "A Roman City in Ancient China", in Greece and Rome, Second Series, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Oct., 1957), pp. 139–148

- ^ a b c Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey (1995). “The Book of the Crossbow”. Dover. ISBN 0-486-28720-3, p. 48

- ^ a b Robert Hardy (1992). “Longbow: A Social and Military History”. Lyons & Burford. ISBN 1-85260-412-3, p. 75

- ^ a b Verbruggen, J.F (1997). The art of warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Boydell&Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-570-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Robert Hardy (1992). “Longbow: A Social and Military History”. Lyons & Burford. ISBN 1-85260-412-3, p. 44

- ^ a b Notes On West African Crossbow Technology

- ^ Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey (1995). “The Book of the Crossbow”. Dover. ISBN 0-486-28720-3, p. 48-53

- ^ The Royal Engineers Journal. 39. The Institution of Royal Engineers: 79. 1925.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ The St. Lawrence

- ^ Chinese news report on crossbows.

- ^ Chinese special forces with crossbows.

- ^ Greek soldiers uses crossbow.

- ^ Turkish special ops.

- ^ [1]<<Antique Montagnard crossbow>>

- ^ Chinese traffic police using crossbows.

- ^ Day Life Serbia report

- ^ bharat-rakshak article on Marine Commandos

- ^ The Guardian.

- ^ Ejercito prepare for deployment.

Sources

- Campbell, Duncan (2003), Greek and Roman Artillery 399 BCE-CE 363, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-634-8

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Schellenberg, Hans Michael (2006), "Diodor von Sizilien 14,42,1 und die Erfindung der Artillerie im Mittelmeerraum" (PDF), Frankfurter Elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde, 3: 14–23

Further Reading

- Nickel, H, ed. (1982). The Art of Chivalry : European arms and armor from the Metropolitan Museum of Art : an exhibition . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The American Federation of Arts.