Human sacrifice in Aztec culture

| Aztec civilization |

|---|

|

| Aztec society |

| Aztec history |

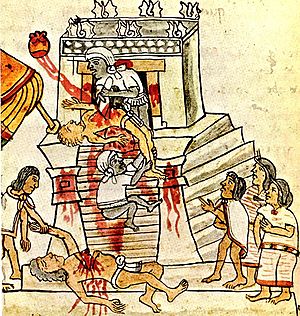

Human sacrifices was a religious practice characteristic of pre-Columbian Aztec civilization, as well as of other Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya and the Zapotec. The extent of the practice is debated by modern scholars.

Spanish explorers, soldiers and clergy who had contact with the Aztecs between 1517, when an expedition from Cuba first explored the Yucatan, and 1521, when Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, made observations of and wrote reports about the practice of human sacrifice. For example, Bernal Díaz's The Conquest of New Spain includes eyewitness accounts of human sacrifices as well as descriptions of the remains of sacrificial victims. In addition, there are a number of second-hand accounts of human sacrifices written by Spanish friars that relate the testimony of native eyewitnesses. The literary accounts have been supported by archeological research. Since the late 1970s, excavations of the offerings in the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan, Teotihuacán's Pyramid of the Moon, and other archaeological sites, have provided physical evidence of human sacrifice among the Mesoamerican peoples.[1][2][3]

A wide variety of explanations and interpretations of the Aztec practice of human sacrifice have been proposed by modern scholars. Most scholars of Pre-Columbian civilization see human sacrifice among the Aztecs as a part of the long cultural tradition of human sacrifice in Mesoamerica.

The antecedents of Mesoamerican sacrifice

The practice of human sacrifice was widespread in the Mesoamerican and in the South American cultures during the Inca Empire.[4][5] Like all other known pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica, the Aztecs practiced human sacrifice. The extant sources describe how the Aztecs sacrificed human victims on each of their eighteen festivities, one festivity for each of their 20-day months.[6] It is unknown if the Aztecs engaged in human sacrifice before they reached the Anahuac valley and started absorbing other cultural influences. The first human sacrifice reported in the sources was the sacrifice and skinning of the daughter of the king Cóxcox of Culhuacán; this story is a part of the legend of the foundation of Tenochtitlan.[7] Several ethnohistorical sources state that under the guidance of Tlacaelel the importance of human sacrifice in Aztec history grew. The Aztecs would perform a series of rituals on nearby tribesman, sacrifice them using an obsidian knife, and then donate their blood to the Aztec god Acolnahuacatl. They would end the sacrificing when he had finished drinking and he was no longer thirsty. This ritual would go on for a whole weekend so as to please the gods.

The role of sacrifice in Mesoamerica

Sacrifice was a common theme in Mesoamerican cultures. In the Aztec "Legend of the Five Suns", all the gods sacrificed themselves so that mankind could live. Some years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, a body of Franciscans confronted the remaining Aztec priesthood and demanded, under threat of death, that they desist from this traditional practice. The Aztec priests defended themselves as follows:

Life is because of the gods; with their sacrifice they gave us life.... They produce our sustenance... which nourishes life.[8]

What the Aztec priests were referring to was a central Mesoamerican belief: that a great, on-going sacrifice sustains the Universe. Everything is tonacayotl: the "spiritual flesh-hood" on earth. Everything —earth, crops, moon, stars and people— springs from the severed or buried bodies, fingers, blood or the heads of the sacrificed gods. Humanity itself is macehualli, "those deserved and brought back to life through penance".[9] A strong sense of indebtedness was connected with this worldview. Indeed, nextlahualli (debt-payment) was a commonly used metaphor for human sacrifice, and, as Bernardino de Sahagún reported, it was said that the victim was someone who "gave his service".

Human sacrifice was in this sense the highest level of an entire panoply of offerings through which the Aztecs sought to repay their debt to the gods. Both Sahagún and Toribio de Benavente (also called "Motolinía") observed that the Aztecs gladly parted with everything: burying, smashing, sinking, slaying vast quantities of quail, rabbits, dogs, feathers, flowers, insects, beans, grains, paper, rubber and treasures as sacrifices. Even the "stage" for human sacrifice, the massive temple-pyramids, was an offering mound: crammed with treasures, grains, soil and human and animal sacrifices that were buried as gifts to the deities. Adorned with the land's finest art, treasure and victims, these temples had become buried offerings under new structures every half a century.

The sacrifice of animals was a common practice for which the Aztecs bred dogs, eagles, jaguars and deer. Objects also were sacrificed by being broken and offered to the gods. The cult of Quetzalcoatl required the sacrifice of butterflies and hummingbirds.

Self-sacrifice was also quite common; people would offer maguey thorns, tainted with their own blood[10] and, like the Maya kings, would offer blood from their tongue, ear lobes, or genitals.[11][12] Blood held a central place in Mesoamerican cultures. The Florentine Codex reports that in one of the creation myths Quetzalcóatl offered blood extracted from a wound in his own genital to give life to humanity. There are several other myths in which Nahua gods offer their blood to help humanity.[13]

Much like the role of sacrifice elsewhere in the world, it thus seems that these rites functioned as a type of atonement for Aztec believers. Their sacrificial hymns describe the victim as "sent (to death) to plead for us", or "consecrated to annul all sin".[14] In one such poem, a warrior-victim announces that "I embrace mankind... I give myself to the community".[15] Aztec society viewed even the slightest tlatlacolli ('sin' or 'insult') as an extremely malevolent supernatural force. For instance, if an adulterer were to enter a house, it was believed that all turkey chicks would perish from tlazomiquiztli ("filth-death").[16] To avoid such calamities befalling their community, those who had erred punished themselves by extreme measures such as slitting their tongues for vices of speech or their ears for vices of listening, and "for a slight [sin they] hanged themselves, or threw themselves down precipices, or put an end to themselves by abstinence".[17]

A great deal of cosmological thought seems to have underlain each of the Aztec sacrificial rites. The most common form of human sacrifice was heart-extraction. The Aztec believed that the heart (tona) was both the seat of the individual and a fragment of the Sun's heat (istli). To this day, the Nahua consider the Sun to be a heart-soul (tona-tiuh): "round, hot, pulsating".[18] In the Aztec view, humanity's "divine sun fragments" were considered "entrapped" by the body and its desires:

Where is your heart?

You give your heart to each thing in turn.

Carrying, you do not carry it...

You destroy your heart on earth— Nahua poem[19]

It also seems that at least in some cases, the strong emphasis given to human sacrifice may have stemmed from the great honour Mesoamerican society bestowed on those who became an ixiptla - that is, a god's representative, image or idol. Ixiptla was the same term used for wooden, stone and dough images of gods. Interestingly, Aztec texts rarely differentiate between human ixiptla and wooden or stone ixiptla. Both types were so elaborately costumed and painted that even the congregation was unsure which were human ixiptla and which were stone or wood (Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, 102). Thus when a victim appeared in full regalia before the congregation, it was said that the divinity had been given 'human form'- that the god now had an ixitli (face) (Duran, Book of the Gods..., 72-73). Duran says such victims were 'worshipped... as the deity' (Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, 42,109,232) or 'as though they had been gods' (Sahagun, Florentine Codex Bk 2: 226, 238-239) (-the original Nahuatl term being nienoteoti'tzinea, literally, 'I consider him a god') (Clavigero, 98). Even whilst still alive, ixiptla victims were honoured, hallowed and addressed (like gods) as 'Lord' and 'Lady' (Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites.., 189) Posthumously, their remains were treated as actual relics of the gods which explains why victims' skulls, bones and skin were often painted, bleached, stored and displayed, or else used as ritual masks and oracles. For example, Diego Duran's informants told him that whoever wore the skin of the victim who had portrayed god Xipe (Our Lord the Flayed One) felt he was wearing a holy relic. He considered himself 'divine' (Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites..176).

Finally, according to the Aztec (and Mesoamerican) world-view, the circumstances in which people died determined the type of afterlife they enjoyed. The Aztecs had meticulously organised death into several types, which each led to specific "heavenly" and "underworld" levels. In the levels Sahagun records, passing away quietly at home was the lowest, as it required the unfortunate soul to undergo numerous torturous trials and journeys, only to culminate in a sombre underworld. By contrast, what the Aztecs termed "a good death" was sacrifice, war (which usually meant sacrifice) or — in the case of women — death whilst giving birth. This kind of end procured for the deceased the second-highest heaven (death in infancy being the highest). Persons who had died sacrificially or in war were called Teo-micqui ("the God-dead") and were said to "go pure... live hard by, nigh unto the Sun... [who] always forever ... rejoice ... [since] the House of the Sun is ... a place of joy."[20]

The 52-year cycle

The cycle of fifty-two years was central to Mesoamerican cultures. The Nahua's religious beliefs were based on a great fear that the universe would collapse after each cycle if the gods were not strong enough. Every fifty-two years a special New Fire ceremony was performed.[21] All fires were extinguished and at midnight a human sacrifice was made. The Aztecs then waited for the dawn. If the Sun appeared it meant that the sacrifices for this cycle had been enough. A fire was ignited on the body of a victim, and this new fire was taken to every house, city and town. Rejoicing was general: a new cycle of fifty-two years was beginning, and the end of the world had been postponed, at least for another 52-year cycle.

Sacrifices to specific gods

Huitzilopochtli

Huitzilopochtli was the tribal deity of the Mexica and, as such, he represented the character of the Mexican people and was often identified with the sun at the zenith, and with warfare, who burned down towns and carried a fire-breathing dragon or serpent. He was considered the primary god of the south and a manifestation of the sun, and a counterpart of the black Tezcatlipoca, the primary god of the north, "a domain associated with Mictlan, the underworld of the dead." [22]

When the Aztecs sacrificed people to Huitzilopochtli (the god with war like aspects) the victim would be placed on a sacrificial stone.[23] Then the priest would cut through the abdomen with an obsidian or flint blade.[24] The heart would be torn out still beating and held towards the sky in honor to the Sun-God; the body would be carried away and either cremated or given to the warrior responsible for the capture of the victim. He would either cut the body in pieces and send them to important people as an offering, or use the pieces for ritual cannibalism. The warrior would thus ascend one step in the hierarchy of the Aztec social classes, a system that rewarded successful warriors.[25]

Tezcatlipoca

Tezcatlipoca was generally considered the most powerful god, the god of night, sorcery and destiny (the name tezcatlipoca means "smoking mirror", or "obsidian"), and the god of the north.[citation needed] The Aztecs believed that Tezcatlipoca created war to provide food and drink to the gods. Tezcatlipoca was known by several epithets including "the Enemy" and "the Enemy of Both Sides", which stress his affinity for discord. He was also deemed the enemy of Quetzalcoatl, but an ally of Huitzilopochtli.[citation needed] Tezcatlipoca had the power to forgive sins and to relieve disease, or to release a man from the fate assigned to him by his date of birth; however, nothing in Tezcatlipoca's nature compelled him to do so. He was capricious and often brought about reversals of fortune, such as bringing drought and famine. He turned himself into Mixcoatl, the god of the hunt, to make fire. To the Aztecs, he was an all-knowing, all-seeing nearly all-powerful god. One of his names can be translated as "He Whose Slaves We Are".[citation needed]

Some captives were sacrificed to Tezcatlipoca in ritual gladiatorial combat. The victim was tethered in place and given a mock weapon. He died fighting against up to four fully armed jaguar knights and eagle warriors.

During the 20-day month of Toxcatl, a young impersonator of Tezcatlipoca would be sacrificed. Throughout a year, this youth would be dressed as Tezcatlipoca and treated as a living incarnation of the god. The youth would represent Tezcatlipoca on earth; he would get four beautiful women as his companions until he was killed. In the meantime, he walked through the streets of Tenochtitlan playing a flute. On the day of the sacrifice a feast would be held in Tezcatlipoca's honor. The young man would climb the pyramid, break his flute and surrender his body to the priests. Sahagún compared it to the Christian Easter.[26]

Huehueteotl

To appease Huehueteotl, the fire god and a senior deity, the Aztecs had a ceremony where they prepared a large feast at the end of which they would burn captives and before they died they would be taken from the fire and their hearts would be cut out. Motolinía and Sahagún reported that the Aztecs believed that if they did not placate Huehueteotl a plague of fire would strike their city. The sacrifice was considered an offering to the deity.[27]

Tlaloc

Tlaloc was the god of rain. The Aztecs believed that if sacrifices were not supplied for Tlaloc, rain would not come and their crops would not flourish. Leprosy and rheumatism, diseases caused by Tlaloc, would infest the village. Tlaloc required the tears of the young as part of the sacrifice. The priests made the children cry during their way to immolation: a good omen that Tlaloc would wet the earth in the raining season. In the Florentine Codex, also known as General History of the Things of New Spain, Sahagún wrote:

They offered them as sacrifices to [Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue] so that they would give them water.[28]

Xipe Totec

God of the east and water, he wore human skin and was a patron for craftsmen. He was a god of maize and was associated with rain.

The table below shows the festivals of the 18-month year of the Aztec calendar and the deities with which the festivals were associated. In History of the Things of New Spain Sahagún confesses he was aghast at the fact that, during the first month of the year, the child sacrifices were approved by their own parents, who also ate their children.[29]

| N° | Name of the Mexican month and its Gregorian equivalent | Deities and human sacrifices | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Atlacacauallo (from February 2 to February 21) | Tláloc, Chalchitlicue, Ehécatl | Sacrifice of children and captives to the water deities |

| II | Tlacaxipehualiztli (from February 22 to March 13) | Xipe Tótec, Huitzilopochtli, Tequitzin-Mayáhuel | Sacrifice of captives; gladiatorial fighters; dances of the priest wearing the skin of the flayed victims |

| III | Tozoztontli (from March 14 to April 2) | Coatlicue, Tlaloc, Chalchitlicue, Tona | Type of sacrifice: extraction of the heart. Burying of the flayed human skins. Sacrifices of children |

| IV | Hueytozoztli (from April 3 to April 22) | Cintéotl, Chicomecacóatl, Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl | Sacrifice of a maid; of boy and girl |

| V | Toxcatl (from April 23 to May 12) | Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli, Tlacahuepan, Cuexcotzin | Sacrifice of captives by extraction of the heart |

| VI | Etzalcualiztli (from May 13 to June 1) | Tláloc, Quetzalcoatl | Sacrifice by drowning and extraction of the heart |

| VII | Tecuilhuitontli (from June 2 to June 21) | Huixtocihuatl, Xochipilli | Sacrifice by extraction of the heart |

| VIII | Hueytecuihutli (from June 22 to July 11) | Xilonen, Quilaztli-Cihacóatl, Ehécatl, Chicomelcóatl | Sacrifice of a decapitated woman and extraction of her heart |

| IX | Tlaxochimaco (from July 12 to July 31) | Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli | Sacrifice by starvation in a cave or temple |

| X | Xocotlhuetzin (from August 1 to August 20) | Xiuhtecuhtli, Ixcozauhqui, Otontecuhtli, Chiconquiáhitl, Cuahtlaxayauh, Coyolintáhuatl, Chalmecacíhuatl | Sacrifices to the fire gods by burning the victims |

| XI | Ochpaniztli (from August 21 to September 9) | Toci, Teteoinan, Chimelcóatl-Chalchiuhcíhuatl, Atlatonin, Atlauhaco, Chiconquiáuitl, Cintéotl | Sacrifice of a decapitated young woman to Toci, she was skinned and a young man wore her skin; sacrifice of captives by hurling from a height and extraction of the heart |

| XII | Teoleco (from September 10 to September 29) | Xochiquétzal | Sacrifices by fire; extraction of the heart |

| XIII | Tepeihuitl (from September 30 to October 19) | Tláloc-Napatecuhtli, Matlalcueye, Xochitécatl, Mayáhuel, Milnáhuatl, Napatecuhtli, Chicomecóatl, Xochiquétzal | Sacrifices of children, two noble women, extraction of the heart and flaying; ritual cannibalism |

| XIV | Quecholli (from October 20 to November 8) | Mixcóatl-Tlamatzincatl, Coatlicue, Izquitécatl, Yoztlamiyáhual, Huitznahuas | Sacrifice by bludgeoning, decapitation and extraction of the heart |

| XV | Panquetzaliztli (from November 9 to November 28) | Huitzilopochtli | Massive sacrifices of captives and slaves by extraction of the heart |

| XVI | Atemoztli (from November 29 to December 18) | Tlaloques | Sacrifices of children, and slaves by decapitation |

| XVII | Tititl (from December 19 to January 7) | Tona-Cozcamiauh, Ilamatecuhtli, Yacatecuhtli, Huitzilncuátec | Sacrifice of a woman by extraction of the heart and decapitated afterwards |

| XVIII | Izcalli (from January 8 to January 27) | Ixozauhqui-Xiuhtecuhtli, Cihuatontli, Nancotlaceuhqui | Sacrifices of victims representing Xiuhtecuhtli and their women (each four years), and captives. Hour: night, New Fire |

| Nemontemi (from January 28 to February 1) | Five ominous days at the end of the year, no ritual, general fasting | ||

The Flower Wars

It has often been claimed by scholars that the Aztecs resorted to a form of ritual warfare, the Flower War, to obtain living human bodies for the sacrifices in time of peace. This claim however has been severely criticised by scholars such as Ross Hassig[30][31] and Nigel Davies[32] who claim that the main purpose of the Flower Wars was political and not religious and that the number of sacrificial victims obtained through flower wars was insignificant compared to the number of victims obtained through normal political warfare.

According to Diego Durán's History of the Indies of New Spain, and a few other sources that are also based on the Crónica X, the Flower Wars were originally a treaty between the cities of Aztec Triple Alliance and Tlaxcala and Huexotzingo motivated by a famine in Mesoamerica in 1450. Aztec prisoners were also sacrificed in Tlaxcala and Huexotzingo. The capture of prisoners for sacrifices was called nextlaualli ("debt payment to the gods"). These sources however are contradicted by other sources, such as the Codex Chimalpahin, which mentions "Flower Wars" much earlier than the famine of 1450 and against other opponents than the ones mentioned in the treaty.

Because the objective of Aztec warfare was to capture victims alive for human sacrifice, battle tactics were designed primarily to injure the enemy rather than kill him. After towns were conquered their inhabitants were no longer candidates for human sacrifice, only liable to regular tribute. Slaves also could be used for human sacrifice, but only if the slave was considered lazy and had been resold three times.[33]

The sacrifice ritual

Most of the sacrificial rituals took more than two people to perform. In the usual procedure of the ritual, the sacrifice would be taken to the top of the temple.[35] The sacrifice would then be laid on a stone slab by four priests, and his/her abdomen would be sliced open by a fifth priest with a ceremonial knife made of flint. The cut was made in the abdomen and went through the diaphragm. The priest would grab the heart and tear it out, still beating. It would be placed in a bowl held by a statue of the honored god, and the body thrown down the temple's stairs.[36] The body would land on a terrace at the base of the pyramid called an apetlatl [aˈpet͡ɬat͡ɬ].[34]

Before and during the killing, priests and audience (who gathered in the plaza below) stabbed, pierced and bled themselves as autosacrifice (Sahagun, Bk. 2: 3: 8, 20: 49, 21: 47). Hymns, whistles, spectacular costumed dances and percussive music marked different phases of the rite.

The body parts would then be disposed of: the viscera fed the animals in the zoo; the bleeding head was placed on display in the tzompantli, meaning 'hairy skulls'.[37] Not all the skulls in the tzompantlis were victims of sacrifice. In the Anales de Tlatelolco it is described that during the siege of Tlatelolco by the Spaniards, the Tlatelolcas built three tzompantli: two for their own dead and one for the fallen conquerors, including two severed heads of horses.

Other kinds of human sacrifice, which paid tribute to various deities, approached the victims differently. The victim could be shot with arrows (in which the draining blood represented the cool rains of spring); die in unequal fighting (gladiatorial sacrifice) or be sacrificed as a result of the Mesoamerican ballgame; burned (to honor the fire god); flayed after being sacrificed (to honor Xipe Totec, "Our Lord The Flayed One"), or drowned.[38]

Estimates of the scope of the sacrifices

Some post-conquest sources report that at the re-consecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs sacrificed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. This number is considered by Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, to be an exaggeration. Hassig states "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the ceremony.[39] The higher estimate would average 14 sacrifices per minute during the four-day consecration. Four tables were arranged at the top so that the victims could be jettisoned down the sides of the temple.[40] Nonetheless, according to Codex Telleriano-Remensis, old Aztecs who talked with the missionaries told about a much lower figure for the reconsecration of the temple, approximately 4,000 victims in total.

Michael Harner, in his 1977 article The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice, estimates the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year. Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, a Mexica descendant and the author of Codex Ixtlilxochitl, estimated that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed annually. Victor Davis Hanson argues that a claim by Don Carlos Zumárraga of 20,000 per annum is "more plausible."[41] Other scholars believe that, since the Aztecs often tried to intimidate their enemies, it is more likely that they could have inflated the number as a propaganda tool.[42] The same can be said for Bernal Díaz's inflated calculations when, in a state of visual shock, he grossly miscalculated the number of skulls at one of the seven Tenochtitlan tzompantlis. The counter argument is that both the Aztecs and Diaz were very precise in the recording of the many other details of Aztec life, and inflation or propaganda would be unlikely. According to the Florentine Codex, fifty years before the conquest the Aztecs burnt the skulls of the former tzompantli. Mexican archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma has unearthed and studied some tzompantlis.[43]

Sacrifices were made on specific days. Sahagún, Juan Bautista de Pomar and Motolinía report that the Aztecs had eighteen festivities each year, one for each Aztec month. They clearly state that in those festivities sacrifices were made. Each god required a different kind of victim: young women were drowned for Xilonen; children were sacrificed to Tláloc; Nahuatl-speaking prisoners to Huitzilopochtli, and a single nahua would volunteer for Tezcatlipoca. The Ramírez Codex states that for the annual festivity of Huitzilopochtli more than sixty prisoners were sacrificed in the main temple, and prisoners were sacrificed in other large Aztec cities as well.

Not all sacrifices were made at the Tenochtitlan temples; a few were made at "Cerro del Peñón", an islet of the Texcoco lake. According to an Aztec source, in the month of Tlacaxipehualiztli (from February 22 to March 13), thirty-four captives were sacrificed in the gladiatorial sacrifice to Xipe Totec.[citation needed] More victims would be sacrificed to Huitzilopochtli in the month Panquetzaliztli (from 9 November to 28 November) according to the Ramírez Codex. This would mean a figure as low as 300 to 600 victims a year. There is little agreement on the actual figure due to the scarcity of archeological evidence.

Every Aztec warrior would have to provide at least one prisoner for sacrifice. All the male population was trained to be warriors, but only the few who succeeded in providing captives could become full-time members of the warrior elite. Those who could not would become macehualli, workers.[citation needed] Accounts also state that several young warriors could unite to capture a single prisoner, which suggests that capturing prisoners for sacrifice was challenging.

There is still much debate as to what social groups constituted the usual victims of these sacrifices. It is often assumed that all victims were 'disposable' commoners or foreigners. However, slaves - a major source of victims - were not a permanent class but rather persons from any level of Aztec society who had fallen into debt or committed some crime (see Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, 131, 260). Likewise, most of the earliest accounts talk of prisoners of war of diverse social status, and concur that virtually all child sacrifices were locals of noble lineage, offered by their own parents (compare Cortes, Letters 105 with Motolinia, History of the Indies 118-119 and Duran, Book of the Gods, 223, 242).

Likewise, it is doubtful if many victims came from far afield. In 1454, the Aztec government forbade the slaying of captives from distant lands at the capital's temples (Duran, The Aztecs: History of the Indes, 141). Duran's informants told him that sacrifices were consequently 'nearly always... friends of the [Royal] House' - meaning warriors from allied states (Duran, The Aztecs: History of the Indies, 141, 198). This probably meant that the average Aztec warrior stood as much chance of procuring a victim as he did of himself becoming one - as the Aztec Emperor reportedly told all captives about to be sacrificed: 'today for you, tomorrow for me' (Tezozomoc Vol.2).

Discussion of primary sources

Early Spanish accounts mention the sacrificial practice of the Aztecs as well as other Mesoamerican cultures in the 16th century. There are numerous depictions of sacrifices in the Mexica statuary, as well as in codices such as the Ríos, Tudela, Telleriano-Remensis, Durán, and Sahagún's Florentine. On the other hand, the pre-Columbian, indigenous codices that depict the rites were not written texts but pictorial and highly symbolic ideographs—the Aztecs did not have a true writing system such as that of the Mayas. Bishop Zumarraga (1528–48) burned all obtainable texts in his religious zeal.[44]

For Mesoamerica as a whole, the accumulated archaeological, iconographical and in the case of the Maya written evidence, indicates that human sacrifice was widespread across cultures and periods, dating back to 600 BC and possibly much earlier. Osteological analyses have also been interpreted as corroborating the texts.[45][46] Pictorial illustrations of sacrifices on Maya ceramics and stelae have also been published.[47]

Accounts from the Grijalva expeditions

In addition to the accounts provided by Sahagún and Durán, there are other important texts to be considered.

Juan de Grijalva, Hernán Cortés, Juan Díaz, Bernal Díaz, Andrés de Tapia, Francisco de Aguilar, Ruy González and the Anonymous Conqueror wrote about the Conquest of Mexico. Martyr d'Anghiera, Lopez de Gomara, Oviedo y Valdes and Illescas, while not in Mesoamerica, wrote their accounts based on interviews with the participants. Bartolomé de Las Casas and Sahagún arrived later to New Spain but had access to direct testimony, especially of the indigenous people. All of these narratives mention and describe the practice of human sacrifice.[citation needed].

Juan Díaz

Juan Díaz, a participant of the 1518 Grijalva expedition, wrote Itinerario de Grijalva before 1520, in which he describes the aftermath of a sacrifice on an island near Veracruz. He said they cut open the body and ripped out the heart.

Bernal Díaz

Bernal Díaz corroborates Juan Díaz's history:

On these altars were idols with evil looking bodies, and that every night five Indians had been sacrificed before them; their chests had been cut open, and their arms and thighs had been cut off. The walls were covered with blood. We stood greatly amazed and gave the island the name isleta de Sacrificios [Islet of Sacrifices].[48]

In The Conquest of New Spain Díaz recounted that, after landing on the coast, they came across a temple dedicated to Tezcatlipoca. "That day they had sacrificed two boys, cutting open their chests and offering their blood and hearts to that accursed idol". Díaz narrates several more sacrificial descriptions on the later Cortés expedition. Arriving at Cholula, they find "cages of stout wooden bars […] full of men and boys who were being fattened for the sacrifice at which their flesh would be eaten".[49] When the conquistadors reached Tenochtitlan, Díaz described the sacrifices at the Great Pyramid:

They strike open the wretched Indian's chest with flint knives and hastily tear out the palpitating heart which, with the blood, they present to the idols […]. They cut off the arms, thighs and head, eating the arms and thighs at ceremonial banquets. The head they hang up on a beam, and the body is […] given to the beasts of prey.[50]

According to Bernal Díaz, the chiefs of the surrounding towns, for example Cempoala, would complain on numerous occasions to Cortés about the perennial need to supply the Aztecs with victims for human sacrifice. It is clear from his description of their fear and resentment toward the Mexicas that, in their opinion, it was no honor to surrender their kinsmen to be sacrificed by them.[51]

Hernán Cortés

Cortés describes similar events in his Letters:

They have a most horrid and abominable custom which truly ought to be punished and which until now we have seen in no other part, and this is that, whenever they wish to ask something of the idols, in order that their plea may find more acceptance, they take many girls and boys and even adults, and in the presence of these idols they open their chests while they are still alive and take out their hearts and entrails and burn them before the idols, offering the smoke as sacrifice. Some of us have seen this, and they say it is the most terrible and frightful thing they have ever witnessed.[52]

The Anonymous Conqueror

The Anonymous Conqueror's Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan details Aztec sacrifices.[53] In Chapter XIV he depicts the temple in which men, women, boys and girls were sacrificed.[54] On Chapter XXIV the Anonymous Conqueror repeatedly claims that the Aztecs were cannibals, sodomites, alcoholics and polygamists.[55] The original Spanish text is lost. The description of the temple was published in the 1556 Ramusio Italian edition.

Assessment of the practice of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice and other forms of torture—self-inflicted or otherwise—were common to many parts of the New World. Thus the rite was nothing new to the Aztecs when they arrived to the Valley of Mexico, nor was it something unique to pre-Columbian Mexico. Other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Purépechas and Toltecs, performed human sacrifices as well and from archaeological evidence, it probably existed since the time of the Olmecs (1200–400 BC), and perhaps even throughout the early farming cultures of the region. Although the extent of human sacrifice is unknown among several Mesoamerican civilizations, such as Teotihuacán,[56] what distinguished Maya and Aztec human sacrifice was the importance with which it was embedded in everyday life.

Diego Durán states that Aztecs made "indifferent or sarcastic remarks" when the Spaniards severely criticized the rite. In his Book of the Gods and Rites some of the Nahuas even ridiculed the Christian sensibilities. Instead, they asked the Spaniards to applaud:

The sacrifice of human beings...the honored oblation of great lords and noblemen. They remember these things and tell of them as if they had been great deeds.[57]

Although Aztec accounts mention some victims who wept, “faltered...weakened” or “lost control of their bowels” when going to be sacrificed,[58] this reaction does not seem to have been the norm, as when this occurred, it was viewed as a bad omen[59]—a tetlazolmictiliztli ("insult to the gods")[59] that had to be atoned. Such victims were hurriedly taken aside and slain amidst the congregation's sarcastic jeers of “he (the victim has) quite acquitted himself as a man”.[60] The conquistadors Cortés and Alvarado found that some of the sacrificial victims they freed “indignantly rejected [the] offer of release and demanded to be sacrificed”.[61] Likewise, their slayers, the native priests, were expected to be “kind...never harms anyone” according to Sahagun's informants.

What has been gleaned from all of this is that the sacrificial role entailed a great deal of social expectation and a certain degree of acquiescence. Sahagún's informants told him that key roles were reserved for persons who were considered “charming, quick, dances with feeling…without [moral] defects…of good understanding…good mannered”.[62] For many rites, the victim had such a quantity of prescribed duties that it is difficult to imagine how the accompanying festival would have progressed without some degree of compliance on the part of the victim. For instance, victims were expected to bless children, greet and cheer passers-by, hear people's petitions to the gods, visit people in their homes, give discourses and lead sacred songs, processions and dances.[63] The works of Clendinnen and Brundage imply that only a few select victims had this kind of role, but the Florentine Codex and Duran both make no such distinctions, stating that “those who had to die performed many ceremonies…[and] these [pre-sacrificial] rites were performed in the case of all the prisoners, each in turn”.[64]

Sacrifices were ritualistic and symbolic acts accompanying huge feasts and festivals. Victims usually died in the "center stage" amid the splendor of dancing troupes, percussion orchestras, elaborate costumes and decorations, carpets of flowers, crowds of thousands of commoners, and all the assembled elite. Aztec texts frequently refer to human sacrifice as neteotoquiliztli, “the desire to be regarded as a god”.[65] For each festival, at least one of the victims took on the paraphernalia, habits, and attributes of the god or goddess whom they were dying to honor or appease. Particularly the young man who was indoctrinated for a year to submit himself to Tezcatlipoca's temple was the Aztec equivalent of a celebrity, being greatly revered and adored to the point of people “kissing the ground” when he passed by.[66]

Proposed explanations of Aztec human sacrifice

The nutritional explanation

Scholars Michael Harner[68] and Marvin Harris have argued that the motivation behind human sacrifice among the Aztecs was actually the cannibalization of the sacrificial victims. While there is universal agreement that the Aztecs practiced sacrifice, there is a lack of scholarly consensus as to whether cannibalism was widespread. At one extreme, anthropologist Marvin Harris, author of Cannibals and Kings, has propagated the claim, originally proposed by Harner, that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward, since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins. This claim has been refuted by Bernard Ortíz Montellano who, in his studies of Aztec health, diet, and medicine,[69][70] demonstrates that while the Aztec diet was low in animal proteins, it was rich in vegetable proteins. Ortiz also points to the preponderance of human sacrifice during periods of food abundance following harvests compared to periods of food scarcity, the insignificant quantity of human protein available from sacrifices and the fact that aristocrats already had easy access to animal protein.[71]

The political explanation

The high-profile nature of the sacrificial ceremonies indicates that human sacrifice played an important political function.[citation needed] The Mexica used a sophisticated package of psychological weaponry to maintain their empire, aimed at instilling a sense of fear into their neighbours. The Aztecs controlled a large empire of tribute-paying vassal tribes. The population of native Aztecs was very small compared to the population of the area they controlled. The Aztecs were vulnerable: they would have been outnumbered had their vassal tribes formed alliances and rebelled. To sow dissension among the vassals the Aztecs demanded human victims as part of the annual tribute. The vassals would raid each other to capture prisoners. This encouraged animosity between the vassals and strengthened Aztec political rule. This was a method of political control which was innovative and perhaps unique in human history.[citation needed]

European empires, in contrast, were typically secured through the creation of garrisons and installation of puppet governments in conquered towns or settlements. The Mexica used human sacrifice as a weapon of terror even against the Spanish conquistadors,[citation needed] whose fallen victims were sacrificed and sometimes skinned and their bloody heads placed at the tzompantli. From across the empire even the chiefs of enemy towns were invited, or in the case of tributary towns obliged, to attend sacrificial ceremonies in Tenochtitlan. Their refusal would be considered an act of defiance against the Mexica.[original research?]

The psychological explanation

For Lloyd deMause it is significant that the victims were invested of a profound cosmological meaning. According to him and a minority of academics who subscribe to an alternative school of thought, "psychohistory", human sacrifices, including sacrifices in Mesoamerica, were an unconscious form of response to the traumatogenic modes of childrearing.[72] DeMause in particular considers the Aztecs' practice of sacrifice as displacement.[73]

The ecological explanation

George Murdock and C. Provost (1973)[74] found that of all societies that have practiced human sacrifice all but one had population densities in excess of 26 people per square mile. They found a significant positive correlation of human sacrifice with high populations and inadequate food storage combined with internal warfare for land and resources. However, there was also a lack of correlation between human sacrifice and actual crop failures or famines which points to population dynamics rather than population density per se. In comparison with other societies with human sacrifice, the Aztecs were extreme in several areas. As well as the magnitude of the sacrifices, they also had the highest level of warfare for land and resources, were the only society with a high risk of famine and had the highest population pressures with more than 500 people per square mile. Ecological factors alone are not sufficient to account for human sacrifice and it is posited that religious beliefs have a significant effect on motivation.[71]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Matos-Moctezuma, Eduardo (1986). Vida y muerte en el Templo Mayor. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- ^ "Evidence May Back Human Sacrifice Claims" By Mark Stevenson

- ^ "Grisly Sacrifices Found in Pyramid of the Moon" By LiveScience Staff.

- ^ Acosta, Valerie (2003). "El sacrificio humano en Mesoamérica". Arqueología mexicana. XI (63): 16–21.

- ^ Reinhard, Johan (November 1999). "A 6,700 metros niños incas sacrificados quedaron congelados en el tiempo". National Geographic, Spanish version: 36–55.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España, ed. a cargo de Ángel Ma. Garibay (México: Editorial Porrúa, 2006), chapters XX to XXXVIII

- ^ Thema, Equipo (2002). Los aztecas. Ediciones Rueda. pp. 39–40.

- ^ Nicholson, Henry B. (1971). (in) Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press. p. 402.

- ^ León-Portilla (1963, p.111).

- ^ Durán, Fr. Diego (1967). Historia de las Indias de Nueva España. Porrúa.

- ^ Museo del Templo Mayor, Hall 2

- ^ Cecelia Klein. "The Ideology of Autosacrifice at the Templo Mayor" in E. H. Boone, ed. The Aztec Templo Mayor pp. 293-370. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. 1987 ISBN 0-88402-149-1

- ^ Soustelle, Jacques (2003). La vida cotidiana de los aztecas. Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 102ff. ISBN 968-16-0636-1.

- ^ Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, 232

- ^ MSS Romance de Los ... Folio 27

- ^ Sahagun Bk. 5: 29: 191-192

- ^ Motolinia, History of the Indies, 106-107

- ^ Alan Sandstrom, Corn is Our Life, 1991, 239-240

- ^ Irene Nicholson, Firefly in the Night, 156 & 203

- ^ Sahagun Bk 6: 21

- ^ Matos-Moctezuma, Eduardo (2006). Tenochtitlan. Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 172–73. ISBN 0-520-05602-7.

- ^ Ingham, John M. "Human Sacrifice at Tenochtitlan"

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España (op. cit.), p. 76

- ^ Sahagún, Ibid.

- ^ Duverger, Christian (2005). La flor letal: economía del sacrificio azteca. Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 83–93.

- ^ Sahagún, Op. cit., p. 79

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España (op. cit.), p. 83

- ^

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino (1950–1959). Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. 1561-82., trans. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe: School of American Research and the University of Utah. III, 5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España, ed. a cargo de Ángel Ma. Garibay (México: Editorial Porrúa, 2006). p. 97

- ^ Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1.

- ^ Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas". Arqueología mexicana. XI: 46–51.

- ^ Davies, Nigel (1968). Los Señorios independientes del Imperio Azteca. Mexico D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

- ^ Duverger, Christian (2005). La flor letal. Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 81.

- ^ a b Nahuatl dictionary.(1997). Wired humanities project. Retrieved September 2, 2012, from link.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España (op. cit.), p. 88

- ^ Duverger, Christian (2005). La flor letal. Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 139–140.

- ^ Duverger, Ibid., 171

- ^ Duverger (op. cit.), pages 157-167

- ^ Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas". Arqueología mexicana. XI: 47.

- ^ Victor Davis Hanson (2000), Carnage and Culture, Doubleday, New York, pp. 194-195. Hanson, who accepts the 80,000+ estimate, also notes that it exceeded "the daily murder record at either Auschwitz or Dachau."

- ^ Hanson, p. 195.

- ^ Duverger (op. cit), 174-77

- ^ Matos-Moctezuma, Eduardo (2005). Muerte a filo de obsidiana. Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 111–124.

- ^ George Holtker, "Studies in Comparative Religion", The Religions of Mexico and Peru, Vol 1, CTS

- ^ [1] - "Ritual Sacrifice and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacán, México" By George L. Cowgill

- ^ [2] - "Analysis of Kaqchikel Skeletons: Iximché, Guatemala" By Stephen L. Whittington & Robert H. Tykot

- ^ Stuart, David (2003). "La ideología del sacrificio entre los mayas". Arqueología mexicana. XI (63): 24–29.

- ^ Díaz, Bernal (2005) [1632]. Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva España (Introducción y notas de Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas). Editorial Porrúa. p. 24.

- ^ Díaz (op. cit.), p. 150

- ^ [3] Dinesh D'Souza's article

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain, chap. XLVI

- ^ Cortés, Hernán (2005) [1523]. Cartas de relación. México: Editorial Porrúa. p. 26. "Y tienen otra cosa horrible y abominable y digna de ser punida que hasta hoy no habíamos visto en ninguna parte, y es que todas las veces que alguna cosa quieren pedir a sus ídolos para que más acepten su petición, toman muchas niñas y niños y aun hombre y mujeres de mayor edad, y en presencia de aquellos ídolos los abren vivos por los pechos y les sacan el corazón y las entrañas, y queman las dichas entrañas y corazones delante de los ídolos, y ofreciéndolos en sacrificio aquel humo. Esto habemos visto algunos de nosotros, y los que lo han visto dicen que es la más cruda y espantosa cosa de ver que jamás han visto".

- ^ [4] - Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan, México, Chapter XV, written by a Companion of Hernán Cortés, The Anonymous Conqueror.

- ^ [5] – Ibid., Chapter XIV

- ^ [6] – Ibid., Chapter XXIV

- ^ [7] DNA analysis shows that the Teotihuacan civilization brought human victims from distant towns.

- ^ Diego Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, p. 227

- ^ Sahagun Bk 2: 81

- ^ a b Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, 132

- ^ Sahagun Bk 2:21)

- ^ Bernal Diaz, The Conquest of New Spain, p. 159)

- ^ Sahagun Bk 2: 24: 68-69

- ^ Sahagun Bk 5: 8; Bk 2: 5:9; Bk 2:24:68-69

- ^ cf. Sahagun Bk 2:5:9 and Duran, Book of the Gods...p. 112.

- ^ Duran, Book of the Gods and Rites, p. 177 Note 4

- ^ Sahagún, Historia general, op. cit, p. 104

- ^ Website of the British Museum.

- ^ Harner, Michael (1977). "The Ecological Basis for Aztec Sacrifice". American Ethnologist. 4 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1525/ae.1977.4.1.02a00070.

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard R. (1990). Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1562-9.

- ^ Ortiz De Montellano, Bernard R. (1983). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris". American Anthropologist, New Series. 85 (2): 403–406. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130.

- ^ a b Winkelman Michael Aztec human sacrifice: Cross-cultural assessments of the ecological hypothesis Ethnology Vol 37 No 3 1998 Pg 285-298

- ^ Godwin, Robert (2004). One Cosmos under God. Omega Books. pp. 142, 154. ISBN 1-55778-836-7.

- ^ deMause, Lloyd (2002). The Emotional Life of Nations. Karnac. e.g., pp. 31, 289–290, 312, 374, and 410. ISBN 1-892746-98-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Murdock, G. P.; Provost, C. A. (1973). "Measurement of Cultural Complexity". Ethnology. 12 (4): 379–92. doi:10.2307/3773367. JSTOR 3773367.

Bibliography

- Anonymous Conqueror (1917) [ca.1550]. Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan, México (online reproduction by FAMSI, edited by Alec Christensen). Marshall H. Saville (trans. and ed.). New York: The Cortes Society. OCLC 6720413. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- Carrasco, David (1999). City of Sacrifice: The Aztec Empire and the Role of Violence in Civilization. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-4642-6. OCLC 41368255.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1963) [1632]. The Conquest of New Spain. Penguin Classics. J. M. Cohen (trans.) (6th printing (1973) ed.). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044123-9. OCLC 162351797.

- Durán, Diego (1994) [ca.1581]. The History of the Indies of New Spain. Civilization of the American Indian series, #210. Doris Heyden (trans., annot., and introd.) (English translation of Historia de las Indias de Nueva-España y Islas de Tierra Firme ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2649-3. OCLC 29565779.

- Godwin, Robert W. (2004). One Cosmos under God: The Unification of Matter, Life, Mind & Spirit. Saint Paul, MN: Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-836-7. OCLC 55131504.

- Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 188. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1. OCLC 17106411.

Ingham, John M. "Human Sacrifice at Tenochtitln." Society for Comparative Studies in Society and History 26 (1984): 379-400.

- León-Portilla, Miguel (1963). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Náhuatl Mind. Civilization of the American Indian series, #67. Jack Emory Davis (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 181727.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (1998). Vida y muerte en el Templo Mayor (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-5712-8. OCLC 40997904.

- Ortiz De Montellano, Bernard R. (June 1983). "Counting Skulls: Comment on the Aztec Cannibalism Theory of Harner-Harris". American Anthropologist. 85 (2). Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association: 403–406. doi:10.1525/aa.1983.85.2.02a00130. OCLC 1479294.

- Ortiz De Montellano, Bernard R. (1990). Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1562-9. OCLC 20798977.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de (1950–82) [ca. 1540–85]. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 13 vols. in 12. vols. I-XII. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson (eds., trans., notes and illus.) (translation of Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España ed.). Santa Fe, NM and Salt Lake City: School of American Research and the University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-082-X. OCLC 276351.

- Schele, Linda; Mary Ellen Miller (1992). Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Justin Kerr (photographer) (2nd paperback edn., reprint with corrections ed.). New York: George Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-1278-2. OCLC 41441466.

External links

- Graulich,Michel. "El sacrificio humano en Mesoamérica". Arqueología mexicana (in Spanish). XI (63): 16–21. Archived from the original on 2010-03-14.

- " The Custom of Aztec Burial" is a part of the Tovar Codex from around 1585

- Aztec human sacrifice was a bloody, fascinating mess