Hymen

| Hymen | |

|---|---|

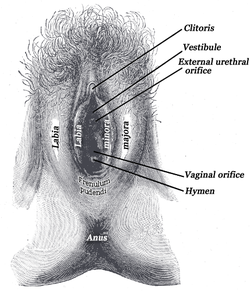

External genital organs of female. The labia minora have been drawn apart. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | hymen vaginae |

| MeSH | D006924 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.008 |

| TA2 | 3530 |

| FMA | 20005 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The hymen is a membrane that surrounds or partially covers the external vaginal opening. It forms part of the vulva, or external genitalia, and is similar in structure to the vagina.[1][2] The hymen does not seem to have a specific physiological function or purpose.[3] In children, although a common appearance of the hymen is crescent-shaped, many shapes are possible. Normal variations of the hymen range from thin and stretchy to thick and somewhat rigid; or it may also be completely absent.[1]

The hymen often, though not always, rips or tears the first time a female engages in penetrative intercourse, which may cause some temporary bleeding and slight discomfort.[4] The hymen can also stretch or tear as a result of various other behaviors; for example, it may be lacerated by disease, injury, medical examination, masturbation or physical exercise. The hymen does not regenerate itself after it is torn,[5] but may be surgically restored in a procedure called hymenorrhaphy. For these reasons, the state of the hymen is not a conclusive indicator of virginity,[2][6] though it continues to be considered so in certain cultures.

Development and histology

The genital tract develops during embryogenesis, from the third week of gestation to the second trimester, and the hymen is formed following the vagina. At week seven, the urorectal septum forms and separates the rectum from the urogenital sinus. At week nine, the Müllerian ducts move downwards to reach the urogenital sinus, forming the uterovaginal canal and inserting into the urogenital sinus. At week twelve, the Müllerian ducts fuse to create a primitive uterovaginal canal called unaleria. At month five, the vaginal canalization is complete and the fetal hymen is formed from the proliferation of the sinovaginal bulbs (where Müllerian ducts meet the urogenital sinus), and normally becomes perforate before or shortly after birth.[7]

The hymen has no nerve innervation. In newborn babies, still under the influence of the mother's hormones, the hymen is thick, pale pink, and redundant (folds in on itself and may protrude). For the first two to four years of life, the infant produces hormones that continue this effect.[8] Their hymenal opening tends to be annular (circumferential).[9]

Past neonatal stage, the diameter of the hymenal opening (measured within the hymenal ring) widens by approximately 1 mm for each year of age.[10] During puberty, the hymenal opening can also be enlarged by tampon or menstrual cup use, pelvic examinations with a speculum, regular physical activity or sexual intercourse.[1] Once a girl reaches puberty, the hymen tends to become very elastic. In one survey, only 43% of women reported bleeding the first time they had intercourse, indicating that the hymens of a majority of women are sufficiently open to prevent tearing.[1][8]

The hymen can stretch or tear as a result of various behaviors, such as the insertion of multiple fingers or items into the vagina, and activities such as gymnastics (doing 'the splits'), or horseback riding.[4] Remnants of the hymen are called carunculae myrtiformes.[6]

A glass or plastic rod of 6 mm diameter having a globe on one end with varying diameter from 10 to 25 mm, called Glaister Keen rod, is used for close examination of the hymen or the degree of its rupture. In forensic medicine, it is recommended by health authorities that a physician who must swab near this area of a prepubescent girl avoid the hymen and swab the outer vulval vestibule instead.[8] In cases of suspected rape or child sexual abuse, a detailed examination of the hymen may be performed, but the condition of the hymen alone is often inconclusive.[2]

Anatomic variations

Normal variations of the hymen range from thin and stretchy to thick and somewhat rigid; or it may also be completely absent.[1][8] The only variation that may require medical intervention is the imperforate hymen, which either completely prevents the passage of menstrual fluid or slows it significantly. In either case, surgical intervention may be needed to allow menstrual fluid to pass or intercourse to take place at all.

Prepubescent girls' hymenal openings come in many shapes, depending on hormonal and activity level, the most common being crescentic (posterior rim): no tissue at the 12 o'clock position; crescent-shaped band of tissue from 1–2 to 10–11 o'clock, at its widest around 6 o'clock. From puberty onwards, depending on estrogen and activity levels, the hymenal tissue may be thicker, and the opening is often fimbriated or erratically shaped.[9] In younger children, a torn hymen will typically heal very quickly. In adolescents, the hymenal opening can naturally extend and variation in shape and appearance increases.[1]

Variations of the female reproductive tract can result from agenesis or hypoplasia, canalization defects, lateral fusion and failure of resorption, resulting in various complications.[10]

- Imperforate:[11][12] hymenal opening nonexistent; will require minor surgery if it has not corrected itself by puberty to allow menstrual fluids to escape.

- Cribriform, or microperforate: sometimes confused for imperforate, the hymenal opening appears to be nonexistent, but has, under close examination, small perforations.

- Septate: the hymenal opening has one or more bands of tissue extending across the opening.

Cultural significance

This section contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (August 2016) |

The hymen is often attributed important cultural significance in certain communities[which?] because of its association with a woman's virginity.[4] In those cultures[which?], an intact hymen is highly valued at marriage in the belief that this is a proof of virginity.[4][13][14] Some women undergo hymenorrhaphy to restore their hymen for this reason.[14]

Womb fury

In the 16th and 17th centuries, medical researchers used the presence of the hymen, or lack thereof, as founding evidence of physical diseases such as "womb-fury", i.e. (female) hysteria. If not cured, womb-fury would, according to these early doctors, result in death.[15][16]

Other animals

Due to similar reproductive system development, many mammals have hymens, including chimpanzees, elephants, manatees, whales, horses and llamas.[17][18]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 61–65

- ^ a b c Perlman, Sally E.; Nakajyma, Steven T.; Hertweck, S. Paige (2004). Clinical protocols in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Parthenon. p. 131. ISBN 1-84214-199-6.

- ^ Blank, Hanne (2008). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 9781596917194.

- ^ a b c d "The Hymen". University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

The hymen can have very important cultural significance in certain cultures because of its association with a woman's virginity.

- ^ Dr Justin J. Lehmiller (February 6, 2015). "Sex Question Friday: Is It Possible For A Woman To Become A Virgin Again?". Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Knight, Bernard (1997). Simpson's Forensic Medicine (11th ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114. ISBN 0-7131-4452-1.

- ^ Healey, Andrew (2012). "Embryology of the female reproductive tract". In Mann, Gurdeep S.; Blair, Joanne C.; Garden, Anne S. (eds.). Imaging of Gynecological Disorders in Infants and Children. Springer. pp. 21–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-85602-3. ISBN 978-3-540-85602-3.

- ^ a b c d McCann, J; Rosas, A. and Boos, S. (2003) "Child and adolescent sexual assaults (childhood sexual abuse)" in Payne-James, Jason; Busuttil, Anthony and Smock, William (eds). Forensic Medicine: Clinical and Pathological Aspects, Greenwich Medical Media: London, a)p.453, b)p.455 c)p.460.

- ^ a b Heger, Astrid; Emans, S. Jean; Muram, David (2000). Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-19-507425-4.

- ^ a b "Imperforate Hymen". WebMD. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

Different normal variants in hymenal configuration are described, varying from the common annular, to crescentic, to navicular ("boatlike" with an anteriorly displaced hymenal orifice). Hymenal variations are rarely clinically significant before menarche. In the case of a navicular configuration, urinary complaints (e.g., dribbling, retention, urinary tract infections) may result. Sometimes, a cribriform (fenestrated), septate, or navicular configuration to the hymen can be associated with retention of vaginal secretions and prolongation of the common condition of a mixed bacterial vulvovaginitis.

- ^ Steinberg, Avraham; Rosner, Fred (2003). Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics. ISBN 1-58330-592-0.

Occasionally, the hymen is harder than normal or it is complete and sealed without there being ... This condition is called imperforate hymen and, at times ...

- ^ DeCherney, Alan H.; Pernoll, Martin L.; Nathan, Lauren (2002). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 602. ISBN 0-8385-1401-4.

Imperforate hymen represents a persistent portion of the urogenital membrane ... It is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract. ...

- ^ "Muslim women in France regain virginity in clinics". Reuters. April 30, 2007.

'Many of my patients are caught between two worlds,' said Abecassis. They have had sex already but are expected to be virgins at marriage according to a custom that he called 'cultural and traditional, with enormous family pressure'.

- ^ a b Sciolino, Elaine; Mekhennet, Souad (June 11, 2008). "In Europe, Debate Over Islam and Virginity". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

'In my culture, not to be a virgin is to be dirt,' said the student, perched on a hospital bed as she awaited surgery on Thursday. 'Right now, virginity is more important to me than life.'

- ^ Berrios GE, Rivière L. (2006) 'Madness from the womb'. History of Psychiatry. 17:223-35.

- ^ The linkage between the hymen and social elements of control has been taken up in Marie Loughlin's book Hymeneutics: Interpreting Virginity on the Early Modern Stage published in 1997

- ^ Blank, Hanne (2007). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 1-59691-010-0. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Blackledge, Catherine (2004). The Story of V. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3455-0.

Hymens, or vaginal closure membranes or vaginal constrictions, as they are often referred to, are found in a number of mammals, including llamas, ...

External links

- Magical Cups and Bloody Brides—the historical context of virginity

- Hymen gallery—Illustrations of hymen types

- 20 Questions About Virginity—Interview with Hanne Blank, author of Virgin: The Untouched History. Discusses relationship between hymen and concept of virginity.

- MedPix Teaching Case Radiology (US - ultrasound) of Hydrocolpos

- Evaluating the Child for Sexual Abuse at the American Family Physician

- My Corona: The Anatomy Formerly Known as the Hymen & the Myths That Surround It Scarleteen, Sex education for the real world

- The Hymen Myth