Illegal drug trade in Turkey

The illegal drug trade in Turkey has played a significant role in its history. Turkish authorities claim that Drug trafficking has provided substantial revenue for illegal groups such as the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK),[1] particularly through marijuana cultivation in south-eastern Turkey,[2] and the 1996 Susurluk scandal showed substantial involvement in drug trafficking on the part of the Turkish deep state. The French Connection heroin trade in the 1960s and 70s was based on poppies grown in Turkey (poppies are a traditional crop in Turkey, with poppy seed used for food and animal fodder as well as for making opium).[3]

Turkish penalties for possession, use and trafficking of illegal drugs are labelled "particularly strict" by the US Embassy in Ankara.[4]

Opium production

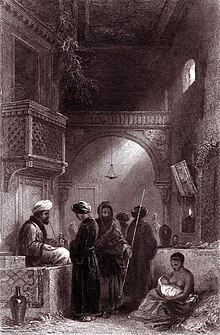

The city of Afyonkarahisar (afyon "poppy, opium", kara "black", hisar "fortress") and its Afyonkarahisar Province was a traditional centre of poppy cultivation. Poppies are a traditional crop in Turkey, with poppy seed used for food and animal fodder as well as for making opium. Already in the early nineteenth century, Turkish opium was being shipped to England and China.[5]

Turkey signed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in 1961, ratifying it in 1967. It was classed as a "traditional opium producing country" under the Convention.[6] In the 1960s, the French Connection heroin trade was based on poppies grown in Turkey, and Turkey was one of the main opium-producing countries. Under international pressure, Turkey reduced the number of provinces where poppies could be grown from 1967 to 1972, before introducing a total ban. This was overturned in 1974, with the introduction of a system for licensed poppy production and state purchasing of poppies for the legal production of poppy-based medicines.[3] The system appears to have been effective: from 1974 to 2000 no seizures of illegal opium derived from Turkish poppies were reported.[7]

Trans-shipment

Due to its strategic geographical location Turkey is a significant trans-shipment point. For example, it is a major route for heroin from Afghanistan to Europe;[7][9] opium production in Afghanistan has been the highest in the world since 1992 (except for the year 2001). According to Interpol, "Turkey is a major staging area and transportation route for heroin destined for European markets.", and is the "anchor point" for the Balkan Route.[10] The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration estimated the 1997 volume of the Turkish heroin traffic at 4–6 tons per month.[8]

In 1992/3 the Turkish Navy intercepted two smuggling vessels, in the Kısmetim-1 incident (3 tons of morphine base) and Lucky-S incident (11 tons of marijuana, 2.5 tons of morphine base). Notable Turkish traffickers include Hüseyin Baybaşin (serving life in the Netherlands for trafficking).

Susurluk scandal

The point of contention of the Susurluk gangs was the European leg of the heroin transportation route, which passes through Turkey. One fifth of the black money is tapped by the gangs as "commission"; a market on the order of $80 billion (1997).[11] According to Doğu Perinçek, the lure of heroin proved irresistible to the state, which suffered a $40–50 billion loss in trade with Iraq due to the U.N. embargo and the Gulf War.[12][13]

The biggest drug cartel was led by Kurdish drug trafficker Hüseyin Baybaşin. The U.K. National Crime Squad estimated that 90% of the heroin in the United Kingdom (25–35 tonnes annually in the late 1990s) was under their control until 2002, when it had a bloody falling-out with its partners in the PKK. He settled in the U.K. after becoming an informer for the HM Customs and Excise office to reveal what he knew, as someone who traveled with a diplomatic passport, about the involvement in heroin trafficking of senior Turkish politicians and officials.[14]

Baybaşin said the most important state official involved in controlling the heroin trade was Şükrü Balcı, who was Istanbul Chief of Police 1979 to 1983.[15]: 598

According to the Independent, the U.K. National Crime Squad had estimated that 90% of the heroin in the United Kingdom was under their control until 2002, when it had a bloody falling-out with its partners in the PKK. He settled in the U.K. after becoming an informer for the HM Customs and Excise office to reveal what he knew, as someone who traveled with a diplomatic passport, about the involvement in heroin trafficking of senior Turkish politicians and officials.[16]

After every single [bank] transaction, certainly half the money would go to the Turkish state. To us it was like a tax in exchange for the all round protection we were getting. If the money was confiscated or we were arrested, our government contacts would come and pick us up and say we were working for the state. Even in Europe, they were still protecting us. When I made my second trip to Europe that year, I saw with my own eyes that all the consulates were in the business. At every consulate, there was a staff member officially assigned to found cultural centres and Turkish schools for example, and we would donate money for them. The Turkish Cultural Association was completely funded by money from the drug trade.

— Hüseyin Baybaşin, Bovenkerk and Yeşilgöz, 1998: 273-4[15]: 598

Another narcotic that was trafficked in significant quantity was Captagon. A notable trafficker was a Turkish businessman Mehmet Ali Yaprak of Gaziantep. Yaprak was ostensibly a businessman with a television channel (Yaprak TV), a radio station, and a tourism company (Hidayet Turizm). However, he also led a feared gang that smuggled Captagon over Syria and Saudi Arabia, according to the MİT report. His tourism company facilitated the trafficking. The report says that Yaprak donated 500 billion Lira[notes 1] to support Ağar's DYP campaign.[17] Upon learning of Yaprak's wealth, Çatlı and a team of 6–7 dressed in police uniform kidnapped Yaprak on 25 May 1996 and took him to a house in Siverek belonging to the Bucak clan.[18] The kidnapping, motivated by the desire to know where the Captagon was coming from and cut Topal out of the loop, was directed by police in Ankara. Yaprak paid 10 million DM in ransom, however Çatlı and his fellow kidnappers received only a small portion of this. When they found out that they had been cheated, they fell out with their overlords in Ankara. They then kidnapped Yaprak a second time and interrogated him, sending one copy of the interrogation tape to Bucak and another to Eymür through MİT agent Müfit Sement. Leveraging the tapes, Çatlı worked out an agreement with Ankara.[17]

After Topal's capture, his friend Haluk Koral called Eymür for help. Topal had also been kidnapped by police chief İbrahim Şahin priorly.[17]

Yaprak was convicted in 1997 for involvement in the assassination of Gaziantep Bar lawyer Burhan Veli Torun, and released due to an amnesty law (Turkish: Şartlı Salıverilme Yasası). In 2002, he was re-imprisoned after being caught with 5 million pills of Captagon. He died in prison, January 2004.[19]

A market in the southeast town of Lice was destroyed by fire. Deputy Fikri Sağlar alleged that Lice was a center of drug processing, and that the factory was moved to Elazığ.[20] Sağlar also said that the Turkish backing for the 1995 Azeri coup d'état attempt was over control of the shipment route from Afghanistan.[21]

Bibliography

- "1998 Report" (PDF). Ankara: Human Rights Foundation of Turkey. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) (contains the Susurluk reports in the annex, and material on the Counter-Guerrilla) Template:En icon

Footnotes

- ^ The Turkish lira was experiencing hyperinflation at the time, so it is difficult to translate into foreign currency. The donation was made towards the elections on 24 December 1995, when the interbank rate was 57,700 Lira/$US. At the beginning of the same year, the parity was 38,900 Lira/$US. The contribution is therefore on the order of $8.7 million to $13m.

References

- ^ mfa.gov.tr, Turkey's Efforts Against The Drug Problem

- ^ Today's Zaman, 24 September 2012, PKK runs major illegal drug trade in Turkey's Southeast Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ceylan Yeğinsu, Hurriyet, 21 November 2008, A flower caught in drug war crossfire

- ^ turkey.usembassy.gov, Penalties for Drug Offenses Archived 2013-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PBS, Opium throughout history

- ^ Jorrit Kamminga, The Political History of Turkey’s Opium Licensing System for the Production of Medicines: Lessons for Afghanistan, SENLIS Council, undated

- ^ a b UNODC, Turkey programme

- ^ a b Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (March 1998). "Europe and Central Asia: continuation, part 3". International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, 1997. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ^ Hurriyet Daily News, 12 August 2010, Seizure of illegal drugs in Turkey on the rise

- ^ Drugs Sub-Directorate (2007-08-02). "Major transportation routes". Interpol. Archived from the original on 2001-09-24. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

The anchor point for the Balkan Route is Turkey, which remains a major staging area and transportation route for heroin destined for European markets. The Balkan Route is divided into three sub-routes: the southern route runs through Turkey, Greece, Albania and Italy; the central route runs through Turkey, Bulgaria, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, and into either Italy or Austria; and the northern route runs from Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania to Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland or Germany.

- ^ Beki, Mehmet Akif (1997-02-12). "The globalization of drugs and money laundering". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 2013-04-18. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Fraser, Suzan (2002-06-21). "Turkey Warns US of Lengthy Iraq War". Common Dreams. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

Turkey has long complained that it has lost some $40 billion in trade with Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War and U.N. embargo.

- ^

"19. DOGU PERINÇEK". TBMM Susurluk Komisyonu Raporu (in Turkish). 1996-12-24. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

Irak'a ambargonun boslugunu Türkiye devletinin eroin ticaretiyle doldurdugunu, resmi makamlara göre Irak'a ambargo yüzünden 40-50 milyar dolar kaybettigimizi, Türkiye'nin disa satimiyla dis alimi arasinda 20 milyar dolar fark oldugunu, yilda 8 ila 15 milyar dolar eroinden girdigini, Irak'a fasulye, mercimek, buzdolabi satmaktan kaybetmis oldugumuz kazanci eroin satarak doldurdugumuzu...

- ^ Cobain, Ian (2006-03-28). "Feared clan who made themselves at home in Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bovenkerk, Frank; Yeşilgöz, Yücel (2004). "The Turkish Mafia and the State". In Cyrille Fijnaut, Letizia Paoli (ed.). Organized Crime in Europe: Concepts, Patterns and Control Policies in the European Union and Beyond. Springer. pp. 598–599. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2765-9. ISBN 1-4020-2615-3.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Cobain, Ian (2006-03-28). "Feared clan who made themselves at home in Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Yaprak, DYP'ye 500 milyar lira yardım etti". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 1998-01-28. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ^ "Turkish Press Scanner: Çatlı was protected by the police". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. 1996-11-06. Archived from the original on 2012-07-01. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ Bel, Yalçın; Sariboga, Veli (2004-01-06). "'Captagon kralı' cezaevinde öldü". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ^ Erkoca, Yurdagul (1998-08-31). "Devletin tepesi haberdar". Radikal (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-23.

Doğan Güreş bu işleri organize etmiş. Genelkurmay Başkanı Güreş asker kökenli Nuri Gündeş'i MİT Müsteşarlığı'na, Mehmet Ağar'ı da Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü'ne tavsiye etmiş. Gündeş'e Köşk izin vermemiş. Onlar da Başbakanlık istihbarat başdanışmanı yapmışlar. MİT de Ağar ve Gündeş'e karşı kendini korumak adına Mehmet Eymür'ü yeniden işe almış. Eymür birinci MİT raporunda Mehmet Ağar'la Nuri Gündeş'in, nasıl yolsuzluklara karıştığını anlatmıştı. Ağar da Mehmet Eymür'le arası bozuk olan ama onun yaptıklarını bilen Korkut Eken'i danışman olarak Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü'ne almış.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ (HRFT 1998, p. 50)