Jelly Roll Morton

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2015) |

Jelly Roll Morton | |

|---|---|

Morton in 1918 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe (possibly spelled Lemott, LaMotte or LaMenthe) |

| Also known as | Jelly Roll Morton |

| Born | October 20, 1890 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 10, 1941 (aged 50) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Ragtime, jazz, jazz blues, Dixieland, swing |

| Occupation(s) | Vaudeville comedian, bandleader, composer, arranger |

| Instrument | Piano |

| Years active | c. 1900–1941 |

Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe (October 20, 1890 – July 10, 1941),[1] known professionally as Jelly Roll Morton, was an American ragtime and early jazz pianist, bandleader and composer who started his career in New Orleans, Louisiana.

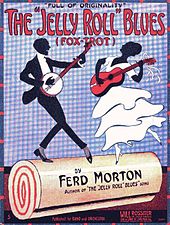

Widely recognized as a pivotal figure in early jazz, Morton is perhaps most notable as jazz's first arranger, proving that a genre rooted in improvisation could retain its essential spirit and characteristics when notated.[2] His composition "Jelly Roll Blues" was the first published jazz composition, in 1915. Morton is also notable for writing such standards as "King Porter Stomp", "Wolverine Blues", "Black Bottom Stomp", and "I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say", the last a tribute to New Orleans musicians from the turn of the 20th century.

Notorious for his arrogance and self-promotion as often as recognized in his day for his musical talents, Morton claimed to have invented jazz outright in 1902—much to the derision of later musicians and critics.[3] The jazz historian, musician, and composer Gunther Schuller says of Morton's "hyperbolic assertions" that there is "no proof to the contrary" and that Morton's "considerable accomplishments in themselves provide reasonable substantiation".[4] However, the scholar Katy Martin has argued that Morton's bragging was exaggerated by Alan Lomax in the book Mister Jelly Roll, and this portrayal has influenced public opinion and scholarship on Morton since.[5]

Biography

Early life and education

Morton was born into a creole of color family in the Faubourg Marigny neighborhood of downtown New Orleans, Louisiana. Sources differ as to his birth date: a baptismal certificate issued in 1894 lists his date of birth as October 20, 1890; Morton and his half-sisters claimed he was born on September 20, 1885. His World War I draft registration card showed September 13, 1884, but his California death certificate listed his birth as September 20, 1889. He was born to F. P. Lamothe and Louise Monette (written as Lemott and Monett on his baptismal certificate). Eulaley Haco (Eulalie Hécaud) was the godparent. Hécaud helped choose his christening name of Ferdinand. His parents lived in a common-law marriage and were not legally married. No birth certificate has been found to date.

Ferdinand started playing music as a child, showing early talent. After his parents separated, his mother married a man named Mouton. Ferdinand took his stepfather's name and anglicized it as "Morton."

Musical career

At the age of fourteen, Morton began working as a piano player in a brothel (or, as it was referred to then, a sporting house). In that atmosphere, he often sang smutty lyrics; he took the nickname "Jelly Roll", which was African American slang for female genitalia.[6][7] While working there, he was living with his religious, church-going great-grandmother; he had her convinced that he worked as a night watchman in a barrel factory.

After Morton's grandmother found out that he was playing jazz in a local brothel, she kicked him out of her house.[8] He said:

When my grandmother found out that I was playing jazz in one of the sporting houses in the District, she told me that I had disgraced the family and forbade me to live at the house... She told me that devil music would surely bring about my downfall, but I just couldn't put it behind me.[8]

Cornetist Rex Stewart recalled that Morton had chosen "the nom de plume 'Morton' to protect his family from disgrace if he was identified as a whorehouse 'professor'."[6]

Tony Jackson, also a pianist at brothels and an accomplished guitar player, was a major influence on Morton's music. Jelly Roll said that Jackson was the only pianist better than he was.

Touring

Around 1904, Morton also started touring in the American South, working with minstrel shows, gambling and composing. His works "Jelly Roll Blues", "New Orleans Blues", "Frog-I-More Rag", "Animule Dance", and "King Porter Stomp" were composed during this period. He got to Chicago in 1910 and New York City in 1911, where future stride greats James P. Johnson and Willie "The Lion" Smith caught his act, years before the blues were widely played in the North.[9]

In 1912–1914, Morton toured with his girlfriend Rosa Brown as a vaudeville act before settling in Chicago for three years. By 1914, he had started writing down his compositions. In 1915, his "Jelly Roll Blues" was arguably the first jazz composition ever published, recording as sheet music the New Orleans traditions that had been jealously guarded by the musicians. In 1917, he followed bandleader William Manuel Johnson and Johnson's sister Anita Gonzalez to California, where Morton's tango, "The Crave", made a sensation in Hollywood.[10]

Vancouver

Morton was invited to play a new Vancouver, British Columbia, nightclub called The Patricia, on East Hastings Street. The jazz historian Mark Miller described his arrival as "an extended period of itinerancy as a pianist, vaudeville performer, gambler, hustler, and, as legend would have it, pimp".[11]

Chicago

Morton returned to Chicago in 1923 to claim authorship of his recently published rag, "The Wolverines", which had become a hit as "Wolverine Blues" in the Windy City. He released the first of his commercial recordings, first as piano rolls, then on record, both as a piano soloist and with various jazz bands.[12]

In 1926, Morton succeeded in getting a contract to record for the largest and most prestigious company in the United States, the Victor Talking Machine Company. This gave him a chance to bring a well-rehearsed band to play his arrangements in Victor's Chicago recording studios. These recordings by Jelly Roll Morton & His Red Hot Peppers are regarded as classics of 1920s jazz. The Red Hot Peppers featured such other New Orleans jazz luminaries as Kid Ory, Omer Simeon, George Mitchell, Johnny St. Cyr, Barney Bigard, Johnny Dodds, Baby Dodds, and Andrew Hilaire. Jelly Roll Morton & His Red Hot Peppers were one of the first acts booked on tours by MCA.[13]

Marriage and family

In November 1928, Morton married the showgirl Mabel Bertrand in Gary, Indiana.

New York City

They moved that year to New York City, where Morton continued to record for Victor. His piano solos and trio recordings are well regarded, but his band recordings suffer in comparison with the Chicago sides, where Morton could draw on many great New Orleans musicians for sidemen.[14] Even though Morton generally had trouble finding musicians who wanted to play his style of jazz, he recorded with such noted musicians as clarinetists Omer Simeon, George Baquet, Albert Nicholas, Wilton Crawley, Barney Bigard, Russell Procope, Lorenzo Tio and Artie Shaw, trumpeters Bubber Miley, Johnny Dunn and Henry "Red" Allen, saxophonists Sidney Bechet, Paul Barnes and Bud Freeman, bassist Pops Foster, and drummers Paul Barbarin, Cozy Cole and Zutty Singleton. His New York sessions failed to produce a hit.[15]

With the Great Depression and the near collapse of the record industry, RCA Victor did not renew Morton's recording contract for 1931. Morton continued playing in New York, but struggled financially. He briefly had a radio show in 1934, then took on touring in the band of a traveling burlesque act for some steady income. In 1935, Morton's 30-year-old composition King Porter Stomp, as arranged by Fletcher Henderson, became Benny Goodman's first hit and a swing standard, but Morton received no royalties from its recordings.[16]

Washington, D.C.

In 1935, Morton moved to Washington, D.C., to become the manager/piano player of a bar called, at various times, the "Music Box", "Blue Moon Inn", and "Jungle Inn" in the African-American neighborhood of Shaw. (The building that hosted the nightclub stands at 1211 U Street NW.) Morton was also the master of ceremonies, bouncer, and bartender of the club. He lived in Washington for a few years; the club owner allowed all her friends free admission and drinks, which prevented Morton from making the business a success.[17]

In 1938, Morton was stabbed by a friend of the owner and suffered wounds to the head and chest. After this incident, his wife Mabel demanded that they leave Washington.[17]

During Morton's brief residency at the Music Box, the folklorist Alan Lomax heard the pianist playing in the bar. In May 1938, Lomax invited Morton to record music and interviews for the Library of Congress. The sessions, originally intended as a short interview with musical examples for use by music researchers in the Library of Congress, soon expanded to record more than eight hours of Morton talking and playing piano. Lomax also conducted longer interviews during which he took notes but did not record. Despite the low fidelity of these non-commercial recordings, their musical and historical importance have attracted numerous jazz fans, and they have helped to ensure Morton's place in jazz history.[18]

Lomax was very interested in Morton's Storyville days in New Orleans and the ribald songs of the time. Although reluctant to recount and record these, Morton eventually obliged Lomax. Because of the suggestive nature of the songs, some of the Library of Congress recordings were not released until 2005.[18]

In his interviews, Morton claimed to have been born in 1885. He was aware that if he had been born in 1890, he would have been slightly too young to make a good case as the inventor of jazz. He said in the interview that Buddy Bolden played ragtime but not jazz; this is not accepted by the consensus of Bolden's other New Orleans contemporaries. The contradictions may stem from different definitions for the terms ragtime and jazz. These interviews, released in different forms over the years, were released on an eight-CD boxed set in 2005, The Complete Library of Congress Recordings. This collection won two Grammy Awards.[18] The same year, Morton was honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Later years

When Morton was stabbed and wounded, a nearby whites-only hospital refused to treat him, as the city had racially segregated facilities. He was transported to a black hospital farther away.[citation needed] When he was in the hospital, the doctors left ice on his wounds for several hours before attending to his eventually fatal injury. His recovery from his wounds was incomplete, and thereafter he was often ill and easily became short of breath. Morton made a new series of commercial recordings in New York, several recounting tunes from his early years that he discussed in his Library of Congress interviews.[citation needed]

Worsening asthma sent him to a New York hospital for three months at one point. He continued to suffer from respiratory problems when visiting Los Angeles with a series of manuscripts of new tunes and arrangements, planning to form a new band and restart his career. Morton died on July 10, 1941, after an eleven-day stay in Los Angeles County General Hospital.

According to the jazz historian David Gelly in 2000, Morton's arrogance and "bumptious" persona alienated so many musicians over the years that no colleagues or admirers attended his funeral.[19] But, a contemporary news account of the funeral in the August 1, 1941, issue of Downbeat says that fellow musicians Kid Ory, Mutt Carey, Fred Washington and Ed Garland were among his pall bearers. The story notes the absence of Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford, both of whom were appearing in Los Angeles at the time. (The article is reproduced in Alan Lomax's biography of Morton, Mister Jelly Roll, University of California Press, 1950.)

Piano style

Morton's piano style was formed from early secondary ragtime and "shout", which also evolved separately into the New York school of stride piano. Morton's playing was also close to barrelhouse, which produced boogie woogie.[20]

Morton often played the melody of a tune with his right thumb, while sounding a harmony above these notes with other fingers of the right hand. This added a rustic or "out-of-tune" sound (due to the playing of a diminished 5th above the melody). This may still be recognized as belonging to New Orleans. Morton also walked in major and minor sixths in the bass, instead of tenths or octaves. He played basic swing rhythms in both the left and right hand.

Compositions

Some of Morton's songs (listed alphabetically): Template:Multicol

- "Big Foot Ham" (a.k.a. "Ham & Eggs")

- "Black Bottom Stomp"

- "Boogaboo"

- "Burnin' the Iceberg"

- "The Crave"

- "Creepy Feelin"

- "Doctor Jazz Stomp"

- "The Dirty Dozen"

- "Fickle Fay Creep"

- "Finger Buster"

- "Freakish"

- "Frog-I-More Rag"

- "Ganjam"

- "Good Old New York"

- "Grandpa's Spells"

- "Jungle Blues"

- "Kansas City Stomp"

- "King Porter Stomp"

- "London Blues"

- "Mama Nita"

- "Milenberg Joys"

- "Mint Julep"

- "Murder Ballad"

- "My Home Is in a Southern Town"

- "New Orleans Bump"

- "Pacific Rag"

- "The Pearls"

- "Pep"

- "Pontchartrain"

- "Red Hot Pepper"

- "Shreveport Stomp"

- "Sidewalk Blues"

- "Stratford Hunch"

- "Sweet Substitute"

- "Tank Town Bump"

- "Turtle Twist"

- "Why?"

- "Wolverine Blues"

Several of Morton's compositions were musical tributes to himself, including "Winin' Boy", "The Jelly Roll Blues", subtitled "The Original Jelly-Roll"; and "Mr. Jelly Lord". In the Big Band era, his "King Porter Stomp", which Morton had written decades earlier, was a big hit for Fletcher Henderson and Benny Goodman; it became a standard covered by most other swing bands of that time. Morton claimed to have written some tunes that were copyrighted by others, including "Alabama Bound" and "Tiger Rag". "Sweet Peter," which Morton recorded in 1926, appears to be the source for the melody of the hit song "All Of Me," ostensibly written by Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons in 1931.

His musical influence continues in the work of Dick Hyman , David Thomas Roberts and Reginald Robinson.[citation needed]

Albums

- The Piano Rolls (Nonesuch, 1997)

- Giants of Jazz (Collectables, 1998)

- Mr. Jelly Roll (Tomato Music, 2003)

Legacy

- Jelly Roll Morton was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and was elected as a charter member of the Gennett Records Walk of Fame.

- In 2008, Jelly Roll Morton was inducted into The Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.[21]

Representation in other media

- Two Broadway shows have featured his music, Jelly Roll and Jelly's Last Jam. The first draws heavily on Morton's own words and stories from the Library of Congress interviews.

- Jelly Roll Morton appears as the piano "professor" in Louis Malle's Pretty Baby, where he is portrayed by actor Antonio Fargas, with piano and vocals played by James Booker.

- Jelly Roll Morton's Last Night at the Jungle Inn: An Imaginary Memoir (1984) was written by the ethnomusicologist and folklorist Samuel Charters, embellishing Morton's early stories about his life.[22]

- Morton and his godmother, who went by the name Eulalie Echo, appear as characters in David Fulmer's mystery novel Chasing the Devil's Tail.

- Jelly Roll Morton is featured in Alessandro Baricco's book Novecento. He is the "inventor of jazz" and the protagonist's rival throughout the book. This book was adapted as a movie: The Legend of 1900, directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. His character is played by the actor Clarence Williams III.

- The play Don't You Leave Me Here, by Clare Brown, which premiered at West Yorkshire Playhouse on 27 September 2008, deals with Morton's relationship with musician Tony Jackson.

- Morton's name is mentioned in "Cornet Man", sung by Barbra Streisand in the Broadway musical Funny Girl (1964).[23]

- Fictional attorney Perry Mason is a fan of Jazz music-including "Jelly Roll Morton" ["The Case of the Missing Melody'].

Selected discography

- 1923/24 (Milestone, 1923–1924)

- Red Hot Peppers Session: Birth of the Hot, The Classic Red Hot Peppers Sessions (RCA Bluebird, 1926–1927)

- The Pearls (RCA Bluebird, 1926–1939)

- Jazz King of New Orleans (RCA Bluebird, 1926–1930)

- The Complete Library of Congress Recordings, Vol. 1–8 (8 CD) (Rounder) (1938)

See also

- List of ragtime composers

- Chord names and symbols (popular music) – Jerry Gates, a professor of Berklee College of Music, tells that he has heard chord symbols came from Ferde Grofé and Jelly Roll Morton.[24]

References

- ^ Scott Yanow (1941-07-10). "Jelly Roll Morton | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ Giddins, Gary & Scott DeVeaux (2009). Jazz. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, ISBN 978-0-393-06861-0

- ^ Critic Scott Yanow writes, "Jelly Roll Morton did himself a lot of harm posthumously by exaggerating his worth, claiming to have invented jazz in 1902. Morton's accomplishments as an early innovator are so vast that he did not really need to stretch the truth."

- ^ Schuller, Gunther (1986). The History of Jazz. Volume 2. Oxford University Press US. p. 136. ISBN 0-19-504043-0.

- ^ Martin, Katy. "The Preoccupations of Mr. Lomax, Inventor of the 'Inventor of Jazz'", Popular Music and Society 36.1, p. 30–39. Taylor and Francis, February 2013. doi:10.1080/03007766.2011.613225.

- ^ a b Stewart, Rex. Boy Meets Horn, Claire P. Gordon, ed. U. of Mich. Press, 1991. Cited in Levin, Floyd (2000). Classic Jazz: A Personal View of the Music and the Musicians. U. of Calif. Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 9780520213609. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Major, Clarence (1994). Juba to Jive: The Dictionary of African-American Slang. New York: Penguin. p. 256. ISBN 9780140513066.

- ^ a b "Culture Shock: The TV Series and Beyond: The Devil's Music: 1920's Jazz". Pbs.org. 2000-02-02. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 42–59. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ "Jelly Rolled into Vancouver". CBC Radio 2. 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: The Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 70–98. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 114–127. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 132–135. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 132–144. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ Reich, Howard; Gaines, William (2003). Jelly's Blues: the Life, Music and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Cambridge MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 0-306-81350-5.

- ^ a b "U Street Jazz – Performers – Prominent Jazz Musicians: Their Histories in Washington, D.C". Gwu.edu. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ a b c "Library of Congress Recordings of Jelly Roll Morton Win at Grammys". Library of Congress. 2006-01-14. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- ^ Gelly, David, Icons of Jazz: A History In Photographs, 1900–2000, San Diego, Ca: Thunder Bay Books, 2000, ISBN 1-57145-268-0

- ^ "Jelly Roll Morton facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Jelly Roll Morton". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- ^ "Louisiana Music Hall of Fame". Louisiana Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ Charters, Samuel Barclay (1984). Jelly Roll Morton's Last Night at the Jungle Inn: An Imaginary Memoir. Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2805-6.

- ^ "Cornet Man Lyrics". MetroLyrics. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Gates, Jerry (2011-02-16). "Chord Symbols As We Know Them Today – Where Did They Come From?". Berklee College of Music. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

Sources

- Dapogny, James. Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton: The Collected Piano Music. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

- The Devil's Music: 1920s Jazz

- Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man; page 486.

- "Ferdinand J. 'Jelly Roll' Morton", A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (1988), pp. 586–587.

- "Jelly", Time magazine, March 11, 1940.

- Ward, Geoffrey C., and Kenneth Burns. Jazz, a History of America's Music 1st Ed. Random House Inc.

Further reading

- Lomax, Alan. Mister Jelly Roll, University of California Press, 1950, 1973, 2001. ISBN 0-520-22530-9

- Wright, Laurie. Mr. Jelly Lord, Storyville Publications, 1980.

- Russell, William. Oh Mister Jelly! A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook, Jazz Media ApS, Copenhagen, 1999.

- Pastras, Phil. Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West, University of California Press, 2001.

- Dapogny, James. Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton: The Collected Piano Music, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

- Gushee, Lawrence. Pioneers of Jazz : The Story of the Creole Band, Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Katy. "The Preoccupations of Mr. Lomax, Inventor of the 'Inventor of Jazz.'" Popular Music and Society 36.1, p. 30–39. Taylor and Francis, February 2013. DOI:10.1080/03007766.2011.613225

- Pareles, Jon. "New Orleans Sauce For Jelly Roll Morton: 'He was the first great composer and jazz master.' Tribute to Jelly Roll Morton." New York Times, 1989, sec. The Arts.

- Reich, Howard and William Gaines. Jelly's Blues: The Life, Music, and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton. Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81350-5

External links

- Ferd 'Jelly Roll' Morton

- Genealogy of Jelly Roll Morton

- Ferd Joseph Morton WWI Draft Registration Card and essay

- Jelly Roll Morton on RedHotJazz.com; biography with audio files of many of Morton's historic recordings

- Mister Jelly Roll, complete 1950 book by Alan Lomax; chronicles the early days of jazz and one of its main developers

- Free scores by Jelly Roll Morton at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Jelly Roll Morton at Find a Grave

- African-American conductors

- African-American jazz composers

- African-American jazz musicians

- African-American jazz pianists

- American conductors (music)

- American jazz bandleaders

- American jazz pianists

- Black conductors

- Dixieland jazz musicians

- Jazz arrangers

- Ragtime composers

- Vaudeville performers

- 1890 births

- 1941 deaths

- Pioneers of music genres

- Jazz musicians from New Orleans

- Louisiana Creole people

- Jazz musicians from Illinois

- Musicians from Chicago

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Burials at Calvary Cemetery, East Los Angeles

- Gennett Records artists

- Vocalion Records artists

- Victor Records artists

- 20th-century conductors (music)

- 20th-century jazz composers

- 20th-century American pianists