Little Round Top

Little Round Top is the smaller of two rocky hills south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—the companion to the adjacent, taller hill named Big Round Top. It was the site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederate troops against the Union left flank on July 2, 1863, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Considered by some historians to be the key point in the Union Army's defensive line that day, Little Round Top was defended successfully by the brigade of Col. Strong Vincent. The 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, commanded by Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Adj. Maj. Holman S. Melcher, fought the most famous engagement there, culminating in a dramatic downhill bayonet charge that is one of the most well-known actions at Gettysburg and in the American Civil War.

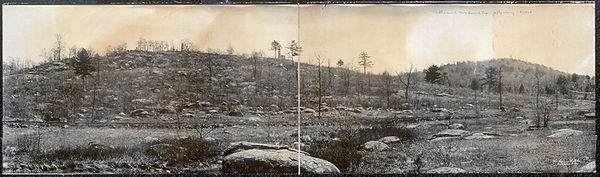

Geography

Little Round Top is a large diabase spur of Big Round Top[1] with an oval crest (despite its name) that forms a short ridgeline with a summit of 63 ft (19 m) prominence above the saddle point[2] to Big Round Top to the south. Located in Cumberland Township, approximately two miles (3 km) south of Gettysburg, with a rugged, steep slope rising 150 feet (46 m) above nearby Plum Run to the west (the peak is 650 feet (198 m) above sea level), strewn with large boulders. The western slope was generally free from vegetation, while the summit and eastern and southern slopes were lightly wooded. Directly to the south was its companion hill, Big Round Top, 130 feet (40 m) higher and densely wooded.[3]

There is no evidence that the name "Little Round Top" was used by soldiers or civilians during the battle. Although the larger hill was known before the battle as Round Top, Round Top Mountain, and sometimes Round Hill, accounts written in 1863 referred to the smaller hill with a variety of names: Rock Hill, High Knob, Sugar Loaf Hill, Broad Top Summit, and granite spur of Round Top. Historian John B. Bachelder, who had an enormous influence on the preservation of the Gettysburg battlefield, personally favored the name "Weed's Hill," in honor of Brig. Gen. Stephen H. Weed, who was mortally wounded on Little Round Top. Bachelder abandoned that name by 1873. One of the first public uses of "Little Round Top" was by Edward Everett in his oration at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery on November 19, 1863.[4]

History

The igneous landform was created 200 million years ago when the "outcrop of the Gettysburg sill" intruded through the Triassic "Gettysburg plain".[5]: 13 Subsequent periglacial frost wedging during the Pleistocene formed the hill's extensive boulders.[6]

Battle of Gettysburg

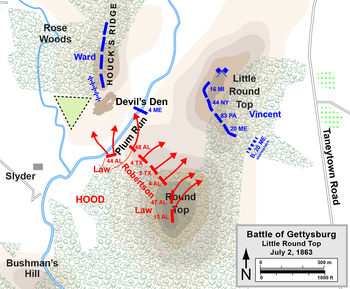

About 4 p.m. on July 2, 1863, Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's First Corps began an attack ordered by General Robert E. Lee that was intended to drive northeast up the Emmitsburg Road in the direction of Cemetery Hill, rolling up the Union left flank.[7] Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's division was assigned to attack up the eastern side of the road, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws's division the western side. Hood's division stepped off first, but instead of guiding on the road, elements began to swing directly to the east in the direction of the Round Tops. Instead of driving the entire division up the spine of Houck's Ridge (the boulder-strewn area known to the soldiers as the Devil's Den), parts of Hood's division detoured over Round Top and approached the southern slope of Little Round Top. There were four probable reasons for the deviation in the division's direction: first, regiments from the Union III Corps were unexpectedly in the Devil's Den area and they would threaten Hood's right flank if they were not dealt with; second, fire from the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters at Slyder's farm drew the attention of lead elements of Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law's brigade, moving in pursuit and drawing his brigade to the right; third, the terrain was rough and units naturally lost their parade-ground alignments; finally, Hood's senior subordinate, General Law, was unaware that he was now in command of the division, so he could not exercise control.[8]

In the meantime, Little Round Top was undefended by Union troops. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, had ordered Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles's III Corps to defend the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, which would have just included Little Round Top. But Sickles, defying Meade's orders, moved his corps a few hundred yards west to the Emmitsburg Road and the Peach Orchard, causing a large salient in the line, which was also too long to defend properly. His left flank was anchored in Devil's Den. When Meade discovered this situation, he dispatched his chief engineer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, to attempt to deal with the situation south of Sickles's position. Climbing Little Round Top, Warren found only a small Signal Corps station there. He saw the glint of bayonets in the sun to the southwest and realized that a Confederate assault into the Union flank was imminent. He hurriedly sent staff officers, including Washington Roebling, to find help from any available units in the vicinity.[9]

The response to this request for help came from Maj. Gen. George Sykes, commander of the Union V Corps. Sykes quickly dispatched a messenger to order his 1st Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. James Barnes, to Little Round Top. Before the messenger could reach Barnes, he encountered Col. Strong Vincent, commander of the third brigade, who seized the initiative and directed his four regiments to Little Round Top without waiting for permission from Barnes. He and Oliver W. Norton, the brigade bugler, galloped ahead to reconnoiter and guide his four regiments into position.[10] Upon arrival on Little Round Top, Vincent and Norton received fire from Confederate batteries almost immediately. On the western slope he placed the 16th Michigan, and then proceeding counterclockwise were the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and finally, at the end of the line on the southern slope, the 20th Maine. Arriving only ten minutes before the Confederates, Vincent ordered his brigade to take cover and wait, and he ordered Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, commander of the 20th Maine, to hold his position, the extreme left of the Army of the Potomac, at all costs. Chamberlain and his 385 men[11] waited for what was to come.[12]

Battle of Little Round Top

The approaching Confederates were the Alabama Brigade of Hood's Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Evander Law. (As the battle progressed and Law realized he was in command of the division, Col. James L. Sheffield was eventually notified to assume brigade command.) Dispatching the 4th, 15th, and 47th Alabama, and the 4th and 5th Texas to Little Round Top, Law ordered his men to take the hill. The men were exhausted, having marched more than 20 miles (32 km) that day to reach this point. The day was hot and their canteens were empty; Law's order to move out reached them before they could refill their water.[13] Approaching the Union line on the crest of the hill, Law's men were thrown back by the first Union volley and withdrew briefly to regroup. The 15th Alabama, commanded by Col. William C. Oates, repositioned further right and attempted to find the Union left flank.[14]

The left flank consisted of the 386 officers and men of the 20th Maine regiment and the 83rd Pennsylvania. Seeing the Confederates shifting around his flank, Chamberlain first stretched his line to the point where his men were in a single-file line, then ordered the southernmost half of his line to swing back during a lull following another Confederate charge. It was there that they "refused the line"—formed an angle to the main line in an attempt to prevent the Confederate flanking maneuver. Despite heavy losses, the 20th Maine held through two subsequent charges by the 15th Alabama and other Confederate regiments for a total of ninety minutes.[15]

On the final charge, knowing that his men were out of ammunition, that his numbers were being depleted, and further knowing that another charge could not be repulsed, Chamberlain ordered a maneuver that was considered unusual for the day: He ordered his left flank, which had been pulled back, to advance with bayonets in a "right-wheel forward" maneuver. As soon as they were in line with the rest of the regiment, the remainder of the regiment charged, akin to a door swinging shut. This simultaneous frontal assault and flanking maneuver halted and captured a good portion of the 15th Alabama.[16] However, Lt. Holman S. Melcher yelled at his fellow soldiers to initiate the charge before the order was given. Chamberlain is credited by some historians with ordering the advance, however most historical research shows that Chamberlain did order the advance but Melcher was the first person to engage with the opposition. Although Chamberlain decided to order the charge before Lt. Melcher requested permission to advance the center of the line toward a boulder ledge where some of the men were wounded and unable to move, Melcher did engage first. As Melcher returned to his men, the shouts of "Bayonet!" were already working their way down the line. It is widely accepted that Chamberlain ordered the advance and Melcher was the first to engage.[17][18]

During their retreat, the Confederates were subjected to a volley of rifle fire from Company B of the 20th Maine, commanded by Captain Walter G. Morrill, and a few of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, who had been placed by Chamberlain behind a stone wall 150 yards to the east, hoping to guard against an envelopment. This group, who had been hidden from sight, caused considerable confusion in the Confederate ranks.[16]

Thirty years later, Chamberlain received a Medal of Honor for his conduct in the defense of Little Round Top. The citation read that it was awarded for "daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and ordering the advance position on the Great Round Top."[19]

Despite this victory, the rest of the Union regiments on the hill were in dire straits. While the Alabamians had pressed their attacks on the Union left, the 4th and 5th Texas were attacking Vincent's 16th Michigan, on the Union right. Rallying the crumbling regiment (the smallest in his brigade, with only 263 men) several times, Vincent was mortally wounded during one Texas charge and was succeeded by Colonel James C. Rice. Vincent died on July 7, but not before receiving a deathbed promotion to brigadier general.[20]

Before the Michiganders could be demoralized, reinforcements summoned by Warren—who had continued on to find more troops to defend the hill—had arrived in the form of the 140th New York and a battery of four guns—Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery, commanded by Lt. Charles E. Hazlett. (Simply maneuvering these guns by hand up the steep and rocky slope of the hill was an amazing achievement. However, this effort had little effect on the action of July 2. The artillerymen were exposed to constant sniper fire and could not work effectively. More significantly, however, they could not depress their barrels sufficiently to defend against incoming infantry attacks.)[21]

The 140th charged into the fray of the battle, driving the Texans back and securing victory for the Union forces on the hill. Col. Patrick "Paddy" O'Rorke, who personally led his regiment in the charge, was killed. Reinforced further by Stephen Weed's brigade of the V Corps, Union forces held the hill throughout the rest of the battle, enduring persistent fire from Confederate sharpshooters stationed around Devil's Den. General Weed was among the victims, and as his old friend Charles Hazlett leaned over to comfort Weed, the artilleryman was also shot dead.[22]

Evening and July 3

Later that day, Little Round Top was the site of constant skirmishing. It was fortified by Weed's brigade, five regiments of the Pennsylvania Reserves, and an Ohio battery of six guns. Most of the stone breastworks that are currently visible on the hill were constructed by these troops after the fighting stopped. Troops of the II, V, VI, and XII Corps passed through the area and also occupied Round Top.[23]

Little Round Top was the starting point for a Union counterattack at dusk on July 2, conducted by the 3rd Division of the V Corps (the Pennsylvania Reserves) under Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford, launched to the west in the direction of the Wheatfield.[24]

On July 3, Hazlett's battery (six 10-pound Parrott rifles, now under the command of Lt. Benjamin F. Rittenhouse)[25] fired into the flank of the Confederate assault known as Pickett's Charge. Near the end of that engagement, General Meade observed from Little Round Top and contemplated his options for a possible counterattack against Lee.[23]

Impact of the battle

Of the 2,996 Union troops engaged at Little Round Top, there were 565 casualties (134 killed, 402 wounded, 29 missing); Confederate losses of 4,864 engaged were 1,185 (279 killed, 868 wounded, 219 missing).[26]

While agreeing that the fighting on Little Round Top was extremely fierce and soldiers on both sides fought valiantly, historians disagree as to the impact of this particular engagement on the overall outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg.[27] The traditional view—one that emerged in the 1880s[28]—is that the left flank of the Union army was a crucial position. An example of this view is from 1900: "If the Confederates had seized [Little Round Top] and dragged some of their artillery up there, as they easily could have done, they would have enfiladed Meade's entire line and made it too unhealthy for him to remain there."[29] An alternative claim is that the hill's terrain offered a poor platform for artillery, and that had Longstreet secured the hill, the Union army would have been forced back to a better defensive position, making the attack on the hill a distraction from the Confederates' true objective. This latter theory is supported by General Lee's writings, in which he appears to have considered Little Round Top irrelevant. In Lee's report after the Gettysburg Campaign, he stated in part, "General Longstreet was delayed by a force occupying the high, rocky hills on the enemy's extreme left, from which his troops could be attacked in reverse as they advanced", suggesting Longstreet was ordered on a course intended to bypass Little Round Top—had the hill been a key objective of the assault, Lee would not have used the phrase "delayed by" in describing the effects of the engagement.[30]

Garry Adelman has countered the argument that a Confederate capture of Little Round Top would have badly hurt the Union effort. Examining the number of troops available in the vicinity in the late afternoon, he determined that at most 2,650 Confederates could have been available to defend the hill after capturing it, and that these men would have been exhausted from combat and short on ammunition. In contrast, 11,600 fresh Union reinforcements were available within a mile, primarily from Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick's VI Corps. In addition, the value of Little Round Top as an artillery position has been overstated—the shape of the crest of the hill forces guns to be placed one behind the other, limiting their effectiveness when engaging targets directly to the north, such as the Union line on Cemetery Ridge.[31]

While Chamberlain and the 20th Maine have gained popularity in the American national consciousness, other historical figures such as Strong Vincent, Patrick O'Rourke, and Charles Hazlett arguably played equal roles in the Union success at Little Round Top. Their deaths at the scene, however, did not allow their personal stories to be told.

Postbellum history

During visits by 13 generals in 1865, points were identified on Little Round Top at which markers were subsequently erected,[32] and a 40 ft (12 m) observatory had been built by 1886[33] before the stone monument with observation deck was dedicated to the 44th New York in 1892. In the late 1880s,[34] the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment monument on Little Round Top was dedicated with a speech by Joshua Chamberlain.[35]

In 1935, two "hairpin curves" of the avenue on Little Round Top were removed by the Continental Contracting Company to create a "by-pass, a stretch of .399 mile," from the Round Top Museum southward to north of the guard station on the south slope at Sykes Avenue and Chamberlain Avenue was subsequently closed. The summit parking lot was also created at this time.[36]

-

Memorial tablet to the Signal Corps embedded in the rock of Little Round Top.

-

Monument for the 30th Infantry, First Pennsylvania Reserves, at the base of Little Round Top. Inscribed in the monument are the words "Co. K recruited at Gettysburg." Dedicated September 1890.

-

Monument in town square: "Company K, in the center of the First [Pennsylvania] Reserves, helped to repulse the Confederate attempt to seize Little Round Top, possession of which was the key to victory in the battle."[37]

-

The 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment monument on Little Round Top is the most popular Gettysburg National Military Park monument that visitors request to see.[38]

-

Monument to Col. Patrick O'Rorke and the 140th New York on Little Round Top.

In popular media

The battle for Little Round Top is a key plot point of Ward Moore's 1953 alternate history novel, Bring the Jubilee. The 1974 novel The Killer Angels, and its 1993 film adaptation, Gettysburg, depicted a portion of this battle.

See also

Notes

- ^ "More Exempts from the Draft". The Baltimore Sun. September 16, 1863. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

among them the heights of Cemetery Hill and the granite spur of Round Top ... have been purchased by Mr. D. McConaughy

- ^ "USGS Elevation Web Service Query". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-02-19. 582.655 (saddle point), 501.2 (Plum Run @ Crawford Rd,

- ^ Adelman, Little Round Top, p. 7; USGS map.

- ^ Frassanito, pp. 243–45. Thus, a famous exchange in the novel The Killer Angels is an anachronism: "Chamberlain said. 'One thing. What's the name of this place? This hill. Has it got a name?' 'Little Round Top,' Rice said. 'Name of the hill you defended. The one you're going to is Big Round Top.'"

- ^ Brown, Andrew (2006--Eleventh printing) [1962]. "GEOLOGY and the Gettysburg Campaign" (PDF). Pennsylvania: Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Geologic Resources Inventory Report" (pdf). Denver, Colorado: Natural Resource Program Center (NPS). 2009. pp. 12, 16, 24. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ Pfanz, p. 153.

- ^ Harman, pp. 55–56; Eicher, p. 526.

- ^ Desjardin, p. 36; Pfanz, p. 5.

- ^ Norton, p. 167. Norton was a member of the 83rd Pennsylvania, which Vincent commanded before becoming its brigade commander.

- ^ Pfanz, p. 232. The 20th Maine had 28 officers and 358 enlisted men.

- ^ Desjardin, p. 36; Pfanz, pp. 208, 216.

- ^ Pfanz, p. 162.

- ^ Desjardin, pp. 51–55; Pfanz, p. 216.

- ^ Pfanz, p. 232; Cross, David F. (June 12, 2006). "Battle of Gettysburg: Fighting at Little Round Top". HistoryNet.com. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ a b Desjardin, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Desjardin, p. 69.

- ^ Melcher, p. 61.

- ^ Desjardin, p. 148. During the Civil War, only enlisted men were eligible to receive the Medal of Honor. In 1893, Congress authorized awards to officers, and numerous medals were granted long after the feats of heroism.

- ^ Pfanz, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Pfanz, pp. 223–24.

- ^ Pfanz, pp. 225–28, 239–40.

- ^ a b Adelman, Little Round Top, p. 15.

- ^ Pfanz, pp. 391–92.

- ^ Hall, p. 314.

- ^ Adelman, Little Round Top, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Compare, for instance, Pfanz, p. 205, Sears, p. 269, and Coddington, p. 388 with Harman, pp. 7–8, 35–47.

- ^ Adelman, Myth of Little Round Top, p. 37.

- ^ "The Battle of Gettysburg: Extracts of the minutes of the meeting of Sterling Price Camp)" (America's Historical Newspaper image). Dallas Morning News (February 25). January 20, 1900. p. 15. Retrieved 2011-01-24. (Major Robbins' letter)

- ^ Harman, p. 36: "How could this Union force, located on the 'high, rocky hills' (a clear reference to the Round Tops), have attacked Longstreet's troops 'in reverse' (from behind) unless the Confederate plans were to march north, staying just west of and passing by these 'rocky hills'?"

- ^ Adelman, Myth of Little Round Top, pp. 61–64, 69-73.

- ^ "The Field of Gettysburgh: Interest Concerning the Great Battle Ground -- Thirteen Generals Revisit the Scene of their Struggle …" (Google News Archive). New York Times. Oct 31, 1865. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Wert, J. Howard (1886). A Complete Handbook of the Monuments and Indications and Guide to the Positions on the Gettysburg Battlefield. p. 92. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- ^ Pullen, pp. 140–41, cites October 1889. Desjardin, p. 153, cites 1889. Hawthorne, p. 52, cites October 3, 1886. Adelman, Little Round Top, p. 24, states that the monument was placed in June 1886.

- ^ James Morgan, "Who Saved Little Round Top: A Response to the Melcher Challenge," Camp Chase Gazette, July 1996.

- ^ Gettysburg Compiler, June 8, 1935

- ^ Minnigh, p. 55. Company K consisted of seasoned veterans of many significant battles, having been recruited in Adams County on May 15, 1861. Company K's engagements, including detailed accounts of eyewitnesses, were recorded by their captain, Henry N. Minnigh, in his book, "A History of Company K."

- ^ Desjardin, pp. 159–63.

References

- Adelman, Garry E. Little Round Top: A Detailed Tour Guide. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57747-062-1.

- Adelman, Garry E. The Myth of Little Round Top. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2003. ISBN 1-57747-097-4.

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4758-4.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Desjardin, Thomas A. Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-57747-034-6.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Frassanito, William A. Early Photography at Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-57747-032-X.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Harman, Troy D. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0054-2.

- Hawthorne, Frederick W. Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments. Gettysburg, PA: Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, 1988. ISBN 0-9657444-0-X.

- LaFantasie, Glenn W. Twilight at Little Round Top. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005. ISBN 978-0-307-38663-2.

- Melcher, Holman S. With a Flash of his Sword: The Writings of. Maj. Holman S. Melcher, 20th Maine Infantry. Edited by William B. Styple. Kearny, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1-883926-00-9.

- Minnigh, Henry N. A History of Company K, 1st (Inft,) Penn'a Reserves. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1998. ISBN 1-57747-040-0. First published 1891 in Duncansville, PA.

- Norton, Oliver W. Army Letters 1861-1865. Chicago: O.L. Deming, 1903. OCLC 518033.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The Second Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8078-1749-X.

- Pullen, John J. Joshua Chamberlain: A Hero's Life and Legacy. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8117-0886-9.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Gottfried, Bradley M. Brigades of Gettysburg. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81175-8.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – June 13, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-30-2.

- Grimsley, Mark, and Brooks D. Simpson. Gettysburg: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8032-7077-1.

- Laino, Philip, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas. 2nd ed. Dayton, OH: Gatehouse Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1.

- Norton, Oliver W. The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top: Gettysburg, July 2, 1863. Gettysburg, PA: Stan Clark Military Books, 1992. ISBN 1-879664-08-9. First published 1913 by Neale Publishing Co.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.

39°47′31″N 77°14′11″W / 39.7920°N 77.2363°W

External links

| External image | |

|---|---|

![Monument in town square: "Company K, in the center of the First [Pennsylvania] Reserves, helped to repulse the Confederate attempt to seize Little Round Top, possession of which was the key to victory in the battle."[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Company_K_Monument%2C_Town_Square%2C_Gettysburg.jpg/180px-Company_K_Monument%2C_Town_Square%2C_Gettysburg.jpg)

![The 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment monument on Little Round Top is the most popular Gettysburg National Military Park monument that visitors request to see.[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/20th_Maine_Monument%2C_Little_Round_Top%2C_Gettysburg_Battlefield%2C_Pennsylvania.jpg/180px-20th_Maine_Monument%2C_Little_Round_Top%2C_Gettysburg_Battlefield%2C_Pennsylvania.jpg)