World Museum

World Museum, with the entrance to Liverpool Central Library on the right | |

| |

Former name | Derby Museum Liverpool Museum |

|---|---|

| Established | 1851 |

| Location | William Brown Street, Liverpool, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°24′36″N 02°58′54″W / 53.41000°N 2.98167°W |

| Visitors | 672,514 (2019)[1] |

| Director | Laura Pye |

| Website | www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk |

World Museum is a large museum in Liverpool, England which has extensive collections covering archaeology, ethnology and the natural and physical sciences. Special attractions include the Natural History Centre and a planetarium. Entry to the museum is free. The museum is part of National Museums Liverpool.

History

[edit]

The current museum is unconnected to the Liverpool Museum of William Bullock, who operated a museum in his house on Church Street, Liverpool, between 1795 and 1809, before he moved it to London.[2][3]

The museum was originally started as the Derby Museum as it comprised the 13th Earl of Derby's natural history collection.[4] It opened in 1851, sharing two rooms on Duke Street with a library. However, the museum proved extremely popular and a new, purpose-built building was required.

Land for the new building, on a street then known as Shaw's Brow (now William Brown Street), opposite St George's Hall, was donated by a local MP and wealthy merchant, Sir William Brown, as was much of the funding for the building which would be known as the William Brown Library and Museum. Around 400,000 people attended the opening of the new building in 1860.[4][5]

Reports detailing the museum's activities and acquisitions were presented to the committee of the borough, city and corporation of Liverpool annually.[6]

In the late 19th century, the museum's collection was beginning to outgrow its building so a competition was launched to design a combined extension to the museum and college of technology. The competition was won by Edward William Mountford and the College of Technology and Museum Extension opened in 1901.[4]

Liverpool, being one of the UK's major ports, was heavily damaged by German bombing during the blitz. While much of the museum's collection was moved to less vulnerable locations during the war, the museum building was struck by German firebombs and suffered heavy damage. Parts of the museum only began to reopen fifteen years later. One of the exhibits destroyed in 1941 was the little 20 ft (6.1 m) yawl City of Ragusa, which twice crossed the Atlantic in 1870 and 1871 with a crew of two men.[7][8]

The museum underwent a £35 million refurbishment in 2005 in order to double the size of the display spaces and make more of the collections accessible for visitors. A central entrance hall and six-storey atrium were created as part of the work. Major new galleries included "World Cultures", the "Bug House" and the "Weston Discovery Centre". On reopening the museum's name was changed again to World Museum.[9]

Collections and exhibits

[edit]Astronomy, space and time

[edit]

The physical sciences collection of World Museum was built after the devastation caused by the incendiary fire of 1941. The collection has expanded, in part, due to transfers from the Decorative Arts Department, Regional History Department, Walker Art Gallery and the Prescot Museum. The collection also contains several significant collections from the Liverpool Royal Institution, Bidston Observatory, later the Proudman Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, and the Physics Department of the University of Liverpool.[10]

Collections such as these are often made up of items of a singular type designed for a particular experiment such as DELPHI or LEP at CERN – the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or the Equatorium, a post-Copernican planetary calculator made to special order in the early 17th century. As a consequence the collection is small but contains a number of significant items.[10]

Planetarium

[edit]World Museum is home to a planetarium. The planetarium, said to be the first planetarium in the UK outside of London, opened in 1970 and has 62 seats.[11] It currently attracts about 90,000 people per year. Shows cover various aspects of space science, including the Solar System and space exploration; there are also special children's shows.

Human history

[edit]

Archaeology and Egyptology

[edit]The archaeological collection includes many fine British objects, including the Anglo-Saxon Kingston brooch and Liudhard medalet, with other objects from the Canterbury-St Martin's hoard.

The Egyptian antiquities collection contains approximately 15,000 objects from Egypt and Sudan and is the most important single component of the Antiquities department's collections. The chronological range of the collection spans from the Prehistoric to the Islamic Period with the largest archaeological site collections being Abydos, Amarna, Beni Hasan, Esna and Meroe.

Over 5,000 Egyptian antiquities were donated to the museum in 1867 by Joseph Mayer[12] (1803–1886), a local goldsmith and antiquarian. Mayer purchased collections from Joseph Sams of Darlington (which contained material from the Henry Salt sale in 1835), Lord Valentia, Bram Hertz, the Reverend Henry Stobart, and the heirs of the Rev. Bryan Faussett. Mayer had displayed his collection in his own ‘Egyptian Museum’ in Liverpool with a purpose of giving citizens who were unable to visit the British Museum in London some idea of the achievements of the Egyptian civilization. On the strength of this substantial donation other people began to donate Egyptian material to the museum, and by the later years of the 19th century the museum had a substantial collection that Amelia Edwards described as being the most important collection of Egyptian antiquities in England next to the contents of the British Museum.

The quality of the Mayer donation is high and there are some outstanding items, but with a few exceptions the entire collection is unprovenanced. The collection was systematically enhanced through subscription to excavations in Egypt. Altogether the museum subscribed to 25 excavations carried out by the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Egypt Exploration Society), the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, and the Egyptian Research Account between 1884 and 1914. It was further developed through links with the Institute of Archaeology at Liverpool University and important collections came to the museum from the excavations of John Garstang who was honorary reader in Egyptian archaeology at Liverpool University, 1902–1907, and Professor of Methods and Practice of Archaeology, 1907–1941. The museum has always had a close relationship with the university; in the early 1920s Percy Newberry, Brunner Professor of Egyptology, and his successor T. Eric Peet, catalogued the collection, assisted with the rearrangement of the displays, and produced a handbook and guide to the Egyptian collection (1st ed., 1923).

In May 1941, at the height of the Liverpool Blitz, a bomb fell on the museum, which was burnt to a shell. Large parts of the collection had been removed at the outbreak of the war, but much remained on display or in store and many artefacts were destroyed. What remained was quite inaccessible and it was not until 1976 that a permanent Egypt gallery was opened in the rebuilt museum. Following the war the museum actively augmented the collection through collecting of new material from excavations in Egypt and Sudan and the purchase of other museum collections. In 1947 and 1949 the material from Garstang's excavations at Meroe came to the museum, and in 1955 Liverpool University placed substantial amounts from its own collections within the museum, including many items from Beni Hasan and Abydos. In 1956 the museum purchased almost the entire non-British collections of the Norwich Castle Museum. This included EES excavated material from Amarna and other sites, botanical remains from Kahun and the private collection of Sir Henry Rider Haggard. In 1973 the collection was increased further by the acquisition of part of the Sir Henry Wellcome Collection, and by the bequest of Colonel J. R. Danson in 1976, which included more material from Amarna and from Garstang's excavations at Abydos.

Postwar a limited Egyptian gallery was opened in 1976 before being expanded in 2008.[13] The gallery between September 2015 and April 2017 to allow it to be improved and expanded.[14][15]

A handy lavishly illustrated guide to the collection is available: Gifts of the Nile (London: HMSO, 1995).

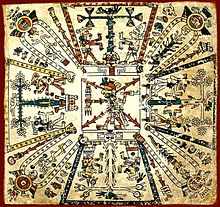

Ethnology

[edit]The ethnology collection at World Museum ranks among the top six collections in the country. The four main areas represented are: Africa, the Americas, Oceania and Asia. The exhibition includes interactive displays.[16]

Natural history

[edit]In the Natural World area can be seen a range of exhibits, including live colonies of insects and historic zoological and botanical exhibits. Visitors can examine the collections up close in the award-winning[17] Clore Natural History Centre, where there are interactive displays.

World Museum's natural history collection is divided into the Botany,[18] Entomology and other Invertebrates,[19][20] Geology and Vertebrate Zoology[21] collections.

Vertebrate zoology

[edit]The 13th Earl of Derby founded the original museum with a major donation of zoological specimens in 1851,[22][23] including many rare[24] and 'type' specimens,[25] the ones that act as standards for the species,[26] animals that died in the Knowsley menagerie,[27] and specimens purchased at major sales (e.g. Leverian collection[28]). The vertebrate zoology collection was vastly increased with the purchase of Canon Henry Baker Tristram's collection of birds[29] in 1896.

The reserve collection includes animals from famous naturalists[30] such as Charles Darwin,[31] Alfred Russel Wallace,[32] John James Audubon, William Thomas March,[33] John Whitehead[34] and Stamford Raffles,[35] transfers from other museums (Selangor Museum,[36] India Museum[37][38]), circuses (Barnum and Bailey[39]) and zoos; and collections from the museum's expeditions[40].

-

Holotype of Ceyx gentiana Tristram (NML-VZ T3959).

-

Holotype of Alaudo chelicuti Stanley (NML-VZ D2304b).

-

Holotype of Chelidon rustica transitiva Hartert (NML-VZ T2057).

-

Syntype of Symmorphus (Lalage) affinis Tristram (NML-VZ T3961).

-

Syntype of Symmorphus (Lalage) affinis Tristram (NML-VZ T3965).

-

Syntype of Peristera histrionica Gould (NML-VZ D1486b).

-

Syntypes of Trichoglossus novaehollandiae septentrionalis Robinson (NML-VZ 23.7.1900.4; NML-VZ 23.7.1900.4a; NML-VZ 23.7.1900.4b).

-

Holotype of Psittacus Taranta Stanley (NML-VZ D704).

-

Syntypes of Psaris fraserii Kaup (NML-VZ D1868; NML-VZ D1868a).

-

Syntypes of Calandrella hermonensis Tristram (NML-VZ T15738; ML-VZ T17770; NML-VZ T17771; NML-VZ T17773).

-

Syntypes of Graucalus lifuensis Tristram (NML-VZ T3506; NML-VZ T3507).

-

Syntype of Chrysoena victor Gould (NML-VZ 1989.66.71).

-

Holotype of Apteryx australis (NML-VZ D180) in World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

There also specimens of several extinct species housed in the museum, including the Liverpool pigeon,[41] the great auk (an egg),[42] the Falkland Islands wolf,[43] the South Island piopio, the Lord Howe swamphen, the Passenger pigeon, the dodo,[44][45] the Pink-headed duck,[46] the Norfolk kākā, the Stephens Island wren, the Bushwren, the Carolina Parakeet, the long-tailed hopping mouse and the thylacine.[46][37]

-

Spotted Green Pigeon, also known as the Liverpool Pigeon (NML-VZ D3538). The only specimen of the species in existence.

-

The Great Auk Egg from the collections of World Museum, National Museums Liverpool (NML-VZ LIV.2016.13).

-

Mounted Lord Howe Island Swamphen (NML-VZ D3213). One of only two specimens of this species in existence.

-

Mounted Dodo

-

Thylacine skull (NML-VZ A26.9.1910.1) held at World Museum, Liverpool.

-

Thylacine skull (NML-VZ 1963.173.131) held at World Museum, Liverpool.

-

Mounted Pink-headed Duck at World Museum NML-VZ 1994.71.193.1

Mounted Pink-headed Duck at World Museum NML-VZ 1994.71.193.1 -

Specimen of Nestor productus NML-VZ D756 from World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Passenger Pigeon from the collections of World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Stephens Island wren (Traversia lyalli) specimen in World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Bushwren (Xenicus longipes) specimen in World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Falklands Island Wolf Skull (NML-VZ D.557) held at World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Falklands Island Wolf Skull (NML-VZ D.557) held at World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Carolina Parakeets (Conuropsis carolinensis) specimens in World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

The museum had extensive public galleries containing vertebrate taxidermy specimens, but these were lost when during the air raids of May 1941 the building was completely destroyed by fire.[47] Some mammal specimens from the original 13th Earl of Derby collection did survive,[48] along with most of the cabinet bird skins. The galleries featured an exhibition of British mammals, amphibians and reptiles, with several cases imaged in 1932.[49]

-

Adder, Grass Snake, Frogs, Toads and Newts.

-

Roe Deer.

-

The Weasel.

-

Squirrels with Drey.

-

The Otter.

-

The Stoat.

-

The Mole.

-

The Polecat.

The British Birds Gallery featured 131 cases, with several cases imaged between 1914 and 1932.[50][51][52] These were the work of taxidermist Mr. J. W. Cutmore who would later produce a series of well-known dioramas at Norwich Museum.[53]

-

The Wren. Case 43.

-

The Reed Warbler. Case 65.

-

The Bearded Titmouse. Case 66.

-

The Cuckoo. Case 70.

-

The Long-eared Owl. Case 82.

-

The Kestrel. Case 83.

-

The Gannet. Case 92.

-

The Mallard or Wild Duck. Case 99.

-

Hooded or Grey Crow Group. Case 102.

-

The Ruff Group. Case 106.

-

The Curlew. Case 125.

-

The Pied Wagtail and Dipper Group. Case 156.

-

One of the Cuckoo Groups. Case 160.

-

The Barn owl Group. Case 180.

-

The Eider Duck Group. Case 193.

-

The Oyster-Catcher Group. Case 198.

-

The Tern and Ringed Plover Group. Case 202.

-

The Great Black-backed Gull Group. Case 208.

-

The Black-throated Diver Group. Case 217.

The current natural history gallery is called Endangered Planet and features a limited number of taxidermy vertebrates in four diorama representing biomes, savanna, tropical rainforest, taiga, tundra.[54] The gallery can be visited virtually.[55]

-

Arctic fox at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Polar bear at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Taxidermy polar bear in the arctic biome diorama at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Seal at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Salmon at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Conservation treatment to the zebra at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Wolves in the Dark Forest biome diorama at World Museum, Liverpool

-

Capybara in the tropical forest biome diorama at World Museum, Liverpool

The collection also includes natural history art works.[56]

-

Painting of Rhodonessa caryophyllacea by Bhawani Das from a live specimen. In the collection of World Museum, Liverpool.

-

Dodo painting held at World Museum, National Museums Liverpool

-

Drawing from the Bulletin of the Liverpool Museums

-

Drawing from the Bulletin of the Liverpool Museums

-

Drawing from the Bulletin of the Liverpool Museums

Botany

[edit]The museum's collections have grown considerably since then and now also include important botanical specimens dating back over 200 years, which represent most of Britain and Ireland's native flora.

The museum had a gallery of economic botany which was destroyed during the air raids of May 1941.[57]

Geology

[edit]The time tunnel gallery displays a series of models across geological time.[58]

The geological collection at World Museum contains over 40,000 fossils as well as extensive rock and mineral collections. Each of these exhibits show information about the origins, structure and history of the planet earth.

Founded in 1858, only seven years after the museum's establishment, much of the original collection was destroyed during the Second World War. The post-war collections have expanded considerably, thanks in part to the acquisition of several significant museum and university collections.

The largest of these was the University of Liverpool's geological collection that includes some 6,600 fossil specimens. The collection covers the following areas: palaeontology, rocks and minerals.

Facial recognition system

[edit]Facial recognition technology, widespread in China, was used at Liverpool's World Museum, during the China's First Emperor and the Terracotta Warriors exhibition. The museum claimed the scanning equipment was used on the advice of local police (Merseyside Police), not the Chinese lenders. In a statement, the director of Big Brother Watch, Silkie Carlo, said that the "authoritarian surveillance tool is rarely seen outside of China."[59]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ William Bullock (1807). A Companion To The Liverpool Museum, Containing a Brief Description of its Curiosities, Natural and Artificial, Works of Art, Etc. Fifth Edition.

- ^ a b c John Millard (April 2010). Liverpool's museum: the first 150 years.

- ^ "The illustrated London news". 1842: volumes. ISSN 0019-2422.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Liverpool (England).; Liverpool (England). Report of the (Free) Public Library, Museum (Liverpool). Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Livepool buildings blitzed (with photo on page 4)". Liverpool Evening Express. British Newspaper Archive. 15 May 1941. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Eterovich, Adam; Žubrinić, Darko (18 June 2013). "Nikola Primorac Croatian captain of City of Ragusa craft sailing from Liverpool to New York and back in 1870". croatia.org. Crown, Croatian World Network. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "BBC - Liverpool - Capital of Culture - World Museum Liverpool opens doors". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Physical sciences". National Museums Liverpool. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ "Celebrating the Planetarium at 50". National Museums Liverpool. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ "Joseph Mayer (1803-86)". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007.

- ^ "New Ancient Egypt Gallery at World Museum to open in April". Museums + Heritage. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Jones, Catherine (2 September 2015). "Look at the World Museum Liverpool's mummies as its Egyptian galleries close for refurbishment". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ McGivern, Hannah (26 April 2017). "Mummy mania makes comeback in Liverpool". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ What do museum objects dream of? | National Museums Liverpool, 24 May 2021, retrieved 2 June 2023

- ^ National Museums & Galleries on Merseyside (1989). Liverpool Museum Natural History Centre.

- ^ "Herbarium". www.gbif.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "Entomology and other Invertebrates". www.gbif.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "The curious survival of Mr. Gaskoin's 'Lucky Shells'". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "Vertebrate Zoology". www.gbif.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ "Lord Edward Smith Stanley, 1775-1851, XIIth Earl of Derby: A review of his biological collections and their importance". Biology Curators Group Newsletter. 1 (6): 20–28. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Clemency; National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, eds. (2002). A passion for natural history: the life and legacy of the 13th Earl of Derby. Liverpool: National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside. ISBN 978-1-902700-14-4.

- ^ "The five new bird species...that weren't". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ R. Wagstaffe (1 December 1978). Type Specimens of Birds in the Merseyside County Museums (formerly City of Liverpool Museums).

- ^ "What's a type? A guide to type specimens". National Museums Liverpool. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Confusing animals that troubled taxidermists". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ Largen, M J (October 1987). "Bird specimens purchased by Lord Stanley at the sale of the Leverian Museum in 1806, including those still extant in the collections of the Liverpool Museum". Archives of Natural History. 14 (3): 265–288. doi:10.3366/anh.1987.14.3.265. ISSN 0260-9541.

- ^ Canon Henry Baker Tristram (1889). Catalogue Of A Collection Of Birds Belonging To H. B. Tristram, D.D., LL.D., F.R.S.

- ^ Merseyside County Council (1981). A list of bird species represented in the collections of Merseyside County Museums.

- ^ Jackson, Ian (4 February 2009). "Charles Darwin's 'Ovenbird' on Show in Liverpool". Art in Liverpool. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Saving the 'land of the orangutan'". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Beavers, Olivia (28 December 2023). "The Jamaican Naturalist William Thomas March (1804-1872): a preliminary review of his zoological and botanical collections". Living World, Journal of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club. ISSN 1029-3299.

- ^ Wilson, John-James (April 2024). "Mammals and birds collected near Mount Kinabalu, Borneo, 1887–1888, now in World Museum, National Museums Liverpool". Archives of Natural History. 51 (1): 182–186. doi:10.3366/anh.2024.0907. ISSN 0260-9541.

- ^ Wilson, John-James (March 2021). "Birds from Sumatra given by Sir Stamford Raffles to Lord Stanley: links to names, types and drawings". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 141 (1): 39–49. doi:10.25226/bboc.v141i1.2021.a4. ISSN 0007-1595.

- ^ "From South East Asia to Liverpool: Ecological Heritage in Museums Collections". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b Clemency Thorne Fisher; Antony Parker; Antony Freestone Roberts (March 1999). Catalogue of the Osteological Specimens in the Collections of the Zoology Department of Liverpool Museum.

- ^ John-James Wilson (February 2024). Lost At Sea Exhibition Hornby Library Liverpool Feb-Apr 2024.

- ^ "Don Pedro: the elephant that died twice". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ Forbes, Henry O.; Forbes, Henry O.; Ogilvie-Grant, W. R. (1903). The natural history of Sokotra and Abdel-Kuri : being the report upon the results of the Conjoint Expedition to these Islands in 1898-9, by Mr. W.R. Ogilvie-Grant ... and Dr. H.O. Forbes ... Liverpool: The Free Public Museums, Henry Young and Sons.

- ^ Holmes, Wesley (18 June 2023). "'Liverpool pigeon' sealed away in a locked cabinet". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ British Museum (Natural History); History), British Museum (Natural) (1962). Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Historical Series. Vol. 3. London: BM(NH).

- ^ Falkland Islands Wolf (Warrah) Skull - 3D model by ThinkSee3D. 29 August 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024 – via sketchfab.com.

- ^ "Breathing new life into the Dodo". National Museums Liverpool. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Jolyon C. Parish (26 January 2015). parishdodomisc6a.

- ^ a b Fisher, C. T. (1981). "SPECIMENS OF EXTINCT ENDANGERED OR RARE BIRDS IN THE MERSEYSIDE COUNTY MUSEUMS LIVERPOOL ENGLAND UK". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 101: 276–285. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Mr. R. Wagstaffe & Miss G. Rutherford (1956). LIVERPOOL PUBLIC MUSEUMS Lower Horseshoe Gallery Handbook To Vertebrate Zoology.

- ^ Largen, M J; Fisher, C T (October 1986). "Catalogue of extant mammal specimens from the collection of the 13th Earl of Derby, now in the Liverpool Museum". Archives of Natural History. 13 (3): 225–272. doi:10.3366/anh.1986.13.3.225. ISSN 0260-9541.

- ^ Mr. R. K. Perry (1932). Handbook and Guide to the British Mammals, etc. on exhibition in the Lord Derby Natural History Museum, Liverpool.

- ^ Joseph A. Clubb (January 1914). Handbook and Guide to the British Birds on Exhibition in the Lord Derby Natural History Museum, Liverpool 1914.

- ^ Joseph A. Clubb (June 1920). Handbook and Guide to the British Birds on Exhibition in the Lord Derby Natural History Museum, Liverpool 1920 [Second Edition].

- ^ Mr. R. K. Perry (March 1932). Handbook and Guide to the British Birds on Exhibition in the Lord Derby Natural History Museum, Liverpool 1932 [Third Edition].

- ^ Liverpool Corporation (November 1955). Liverpool Libraries, Museums & Art Galleries Bulletin Vol. 5 Nos. 1 and 2 November 1955.

- ^ "Dinosaurs and Natural World". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Dinosaurs and Natural World virtual tour". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Art works from the Vertebrate Zoology collection at World Museum, National Museums Liverpool | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Public Museums, Liverpool (1933). Handbook and guide to the Gallery of Economic Botany in the Public Museums, Liverpool. Public Museums, Liverpool. OCLC 6217978.

- ^ City of Liverpool Museums (1966). THE EARTH BEFORE MAN A Guide To The Geological Gallery Liverpool Museum.

- ^ Pes, Javier (16 August 2019). "Privacy Advocates Slam a UK Museum for Using Facial-Recognition Surveillance at Its Terracotta Warriors Show". artnet News. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

External links

[edit]- 1853 establishments in England

- National Museums Liverpool

- Archaeological museums in England

- Natural history museums in England

- Planetaria in the United Kingdom

- Museums in Liverpool

- Collection of the World Museum

- Egyptological collections in England

- Museums of ancient Rome in the United Kingdom

- Museums of ancient Greece in the United Kingdom

- Numismatic museums in the United Kingdom

- Geology museums in England

- Insectariums

- Science museums in England

- Museums established in 1853

- Neoclassical architecture in Liverpool