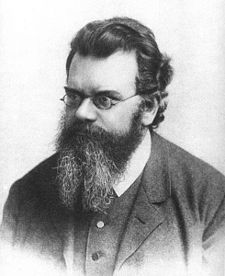

Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Boltzmann | |

|---|---|

Ludwig Boltzmann | |

| Born | Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann February 20, 1844 Vienna, Austrian Empire (present-day Austria) |

| Died | September 5, 1906 (aged 62) |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | |

| Awards | ForMemRS (1899)[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Josef Stefan |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | |

| Signature | |

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (February 20, 1844 – September 5, 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher whose greatest achievement was in the development of statistical mechanics, which explains and predicts how the properties of atoms (such as mass, charge, and structure) determine the physical properties of matter (such as viscosity, thermal conductivity, and diffusion).

Biography

Childhood and education

Boltzmann was born in Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire. His father, Ludwig Georg Boltzmann, was a revenue official. His grandfather, who had moved to Vienna from Berlin, was a clock manufacturer, and Boltzmann's mother, Katharina Pauernfeind, was originally from Salzburg. He received his primary education from a private tutor at the home of his parents. Boltzmann attended high school in Linz, Upper Austria. When Boltzmann was 15, his father died.

Boltzmann studied physics at the University of Vienna, starting in 1863. Among his teachers were Josef Loschmidt, Joseph Stefan, Andreas von Ettingshausen and Jozef Petzval. Boltzmann received his PhD degree in 1866 working under the supervision of Stefan; his dissertation was on kinetic theory of gases. In 1867 he became a Privatdozent (lecturer). After obtaining his doctorate degree, Boltzmann worked two more years as Stefan's assistant. It was Stefan who introduced Boltzmann to Maxwell's work.

Academic career

In 1869 at age 25, thanks to a letter of recommendation written by Stefan,[2] he was appointed full Professor of Mathematical Physics at the University of Graz in the province of Styria. In 1869 he spent several months in Heidelberg working with Robert Bunsen and Leo Königsberger and then in 1871 he was with Gustav Kirchhoff and Hermann von Helmholtz in Berlin. In 1873 Boltzmann joined the University of Vienna as Professor of Mathematics and there he stayed until 1876.

In 1872, long before women were admitted to Austrian universities, he met Henriette von Aigentler, an aspiring teacher of mathematics and physics in Graz. She was refused permission to audit lectures unofficially. Boltzmann advised her to appeal, which she did, successfully. On July 17, 1876 Ludwig Boltzmann married Henriette; they had three daughters and two sons. Boltzmann went back to Graz to take up the chair of Experimental Physics. Among his students in Graz were Svante Arrhenius and Walther Nernst.[3][4] He spent 14 happy years in Graz and it was there that he developed his statistical concept of nature.

Boltzmann was appointed to the Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Munich in Bavaria, Germany in 1890. In 1893, Boltzmann succeeded his teacher Joseph Stefan as Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Vienna.

Final years

Boltzmann spent a great deal of effort in his final years defending his theories. He did not get along with some of his colleagues in Vienna, particularly Ernst Mach, who became a professor of philosophy and history of sciences in 1895. That same year Georg Helm and Wilhelm Ostwald presented their position on Energetics at a meeting in Lübeck. They saw energy, and not matter, as the chief component of the universe. Boltzmann's position carried the day among other physicists who supported his atomic theories in the debate.[5] In 1900, Boltzmann went to the University of Leipzig, on the invitation of Wilhelm Ostwald.[6] After the retirement of Mach due to bad health, Boltzmann returned to Vienna in 1902.[7] In 1903 he founded the Austrian Mathematical Society together with Gustav von Escherich and Emil Müller. His students included Karl Przibram, Paul Ehrenfest and Lise Meitner.

In Vienna, Boltzmann taught physics and also lectured on philosophy. Boltzmann's lectures on natural philosophy were very popular and received considerable attention. His first lecture was an enormous success. Even though the largest lecture hall had been chosen for it, the people stood all the way down the staircase. Because of the great successes of Boltzmann's philosophical lectures, the Emperor invited him for a reception at the Palace.

Boltzmann was subject to rapid alternation of depressed moods with elevated, expansive or irritable moods, likely the symptoms of undiagnosed bipolar disorder. He himself jestingly attributed his rapid swings in temperament to the fact that he was born during the night between Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday.[8] Meitner relates that those who were close to Boltzmann were aware of his bouts of severe depression and his suicide attempts.

On September 5, 1906, while on a summer vacation in Duino, near Trieste, Boltzmann hanged himself during an attack of depression.[9][10] He is buried in the Viennese Zentralfriedhof; his tombstone bears the inscription of the entropy formula:

Philosophy

Boltzmann's kinetic theory of gases seemed to presuppose the reality of atoms and molecules, but almost all German philosophers and many scientists like Ernst Mach and the physical chemist Wilhelm Ostwald disbelieved their existence. During the 1890s Boltzmann attempted to formulate a compromise position which would allow both atomists and anti-atomists to do physics without arguing over atoms. His solution was to use Hertz's theory that atoms were Bilder, that is, models or pictures. Atomists could think the pictures were the real atoms while the anti-atomists could think of the pictures as representing a useful but unreal model, but this did not fully satisfy either group. Furthermore, Ostwald and many defenders of "pure thermodynamics" were trying hard to refute the kinetic theory of gases and statistical mechanics because of Boltzmann's assumptions about atoms and molecules and especially statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics.

Around the turn of the century, Boltzmann's science was being threatened by another philosophical objection. Some physicists, including Mach's student, Gustav Jaumann, interpreted Hertz to mean that all electromagnetic behavior is continuous, as if there were no atoms and molecules, and likewise as if all physical behavior were ultimately electromagnetic. This movement around 1900 deeply depressed Boltzmann since it could mean the end of his kinetic theory and statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics.

After Mach's resignation in Vienna in 1901, Boltzmann returned there and decided to become a philosopher himself to refute philosophical objections to his physics, but he soon became discouraged again. In 1904 at a physics conference in St. Louis most physicists seemed to reject atoms and he was not even invited to the physics section. Rather, he was stuck in a section called "applied mathematics", he violently attacked philosophy, especially on allegedly Darwinian grounds but actually in terms of Lamarck's theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics that people inherited bad philosophy from the past and that it was hard for scientists to overcome such inheritance.

In 1905 Boltzmann corresponded extensively with the Austro-German philosopher Franz Brentano with the hope of gaining a better mastery of philosophy, apparently, so that he could better refute its relevancy in science, but he became discouraged about this approach as well. In the following year 1906 his mental condition became so bad that he had to resign his position. He committed suicide in September of that same year by hanging himself while on vacation with his wife and daughter near Trieste, Italy.[11]

Physics

Boltzmann's most important scientific contributions were in kinetic theory, including the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution for molecular speeds in a gas. In addition, Maxwell–Boltzmann statistics and the Boltzmann distribution over energies remain the foundations of classical statistical mechanics. They are applicable to the many phenomena that do not require quantum statistics and provide a remarkable insight into the meaning of temperature.

Much of the physics establishment did not share his belief in the reality of atoms and molecules — a belief shared, however, by Maxwell in Scotland and Gibbs in the United States; and by most chemists since the discoveries of John Dalton in 1808. He had a long-running dispute with the editor of the preeminent German physics journal of his day, who refused to let Boltzmann refer to atoms and molecules as anything other than convenient theoretical constructs. Only a couple of years after Boltzmann's death, Perrin's studies of colloidal suspensions (1908–1909), based on Einstein's theoretical studies of 1905, confirmed the values of Avogadro's number and Boltzmann's constant, and convinced the world that the tiny particles really exist.

To quote Planck, "The logarithmic connection between entropy and probability was first stated by L. Boltzmann in his kinetic theory of gases".[12] This famous formula for entropy S is[13][14]

where kB is Boltzmann's constant, and ln is the natural logarithm. W is Wahrscheinlichkeit, a German word meaning the probability of occurrence of a macrostate[15] or, more precisely, the number of possible microstates corresponding to the macroscopic state of a system — number of (unobservable) "ways" in the (observable) thermodynamic state of a system can be realized by assigning different positions and momenta to the various molecules. Boltzmann's paradigm was an ideal gas of N identical particles, of which Ni are in the ith microscopic condition (range) of position and momentum. W can be counted using the formula for permutations

where i ranges over all possible molecular conditions. ( denotes factorial.) The "correction" in the denominator is because identical particles in the same condition are indistinguishable.

Boltzmann was also one of the founders of quantum mechanics due to his suggestion in 1877 that the energy levels of a physical system could be discrete.

The equation for S is engraved on Boltzmann's tombstone at the Vienna Zentralfriedhof — his second grave.[16]

The Boltzmann equation

The Boltzmann equation was developed to describe the dynamics of an ideal gas.

where ƒ represents the distribution function of single-particle position and momentum at a given time (see the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution), F is a force, m is the mass of a particle, t is the time and v is an average velocity of particles.

This equation describes the temporal and spatial variation of the probability distribution for the position and momentum of a density distribution of a cloud of points in single-particle phase space. (See Hamiltonian mechanics.) The first term on the left-hand side represents the explicit time variation of the distribution function, while the second term gives the spatial variation, and the third term describes the effect of any force acting on the particles. The right-hand side of the equation represents the effect of collisions.

In principle, the above equation completely describes the dynamics of an ensemble of gas particles, given appropriate boundary conditions. This first-order differential equation has a deceptively simple appearance, since ƒ can represent an arbitrary single-particle distribution function. Also, the force acting on the particles depends directly on the velocity distribution function ƒ. The Boltzmann equation is notoriously difficult to integrate. David Hilbert spent years trying to solve it without any real success.

The form of the collision term assumed by Boltzmann was approximate. However, for an ideal gas the standard Chapman–Enskog solution of the Boltzmann equation is highly accurate. It is expected to lead to incorrect results for an ideal gas only under shock wave conditions.

Boltzmann tried for many years to "prove" the second law of thermodynamics using his gas-dynamical equation — his famous H-theorem. However the key assumption he made in formulating the collision term was "molecular chaos", an assumption which breaks time-reversal symmetry as is necessary for anything which could imply the second law. It was from the probabilistic assumption alone that Boltzmann's apparent success emanated, so his long dispute with Loschmidt and others over Loschmidt's paradox ultimately ended in his failure.

Finally, in the 1970s E. G. D. Cohen and J. R. Dorfman proved that a systematic (power series) extension of the Boltzmann equation to high densities is mathematically impossible. Consequently, nonequilibrium statistical mechanics for dense gases and liquids focuses on the Green–Kubo relations, the fluctuation theorem, and other approaches instead.

The Second Law as a law of disorder

The idea that the second law of thermodynamics or "entropy law" is a law of disorder (or that dynamically ordered states are "infinitely improbable") is due to Boltzmann's view of the second law. In particular, it was his attempt to reduce it to a stochastic collision function, or law of probability following from the random collisions of mechanical particles. Following Maxwell,[17] Boltzmann modeled gas molecules as colliding billiard balls in a box, noting that with each collision nonequilibrium velocity distributions (groups of molecules moving at the same speed and in the same direction) would become increasingly disordered leading to a final state of macroscopic uniformity and maximum microscopic disorder or the state of maximum entropy (where the macroscopic uniformity corresponds to the obliteration of all field potentials or gradients).[18] The second law, he argued, was thus simply the result of the fact that in a world of mechanically colliding particles disordered states are the most probable. Because there are so many more possible disordered states than ordered ones, a system will almost always be found either in the state of maximum disorder – the macrostate with the greatest number of accessible microstates such as a gas in a box at equilibrium – or moving towards it. A dynamically ordered state, one with molecules moving "at the same speed and in the same direction", Boltzmann concluded, is thus "the most improbable case conceivable...an infinitely improbable configuration of energy."[19]

Boltzmann accomplished the feat of showing that the second law of thermodynamics is only a statistical fact. The gradual disordering of energy is analogous to the disordering of an initially ordered pack of cards under repeated shuffling, and just as the cards will finally return to their original order if shuffled a gigantic number of times, so the entire universe must some day regain, by pure chance, the state from which it first set out. (This optimistic coda to the idea of the dying universe becomes somewhat muted when one attempts to estimate the timeline which will probably elapse before it spontaneously occurs.)[20] The tendency for entropy increase seems to cause difficulty to beginners in thermodynamics, but is easy to understand from the standpoint of the theory of probability. Consider two ordinary dice, with both sixes face up. After the dice are shaken, the chance of finding these two sixes face up is small (1 in 36); thus one can say that the random motion (the agitation) of the dice, like the chaotic collisions of molecules because of thermal energy, causes the less probable state to change to one that is more probable. With millions of dice, like the millions of atoms involved in thermodynamic calculations, the probability of their all being sixes becomes so vanishingly small that the system must move to one of the more probable states.[21] However, mathematically the odds of all the dice results not being a pair sixes is also as hard as the ones of all of them being sixes, and since statistically the data tend to balance, one in every 36 pairs of dice will tend to be a pair of sixes. And the cards, when shuffled, will sometimes present a certain temporary sequence order even if in its whole they are disordered.

Energetics of evolution

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Boltzmann's views played an essential role in the development of energetics, the scientific study of energy flows under transformation. In 1922, for example, Alfred J. Lotka referred to Boltzmann as one of the first proponents of the proposition that available energy can be understood as the fundamental object under contention in the biological competition, or life-struggle, between species, and therefore also in the evolution of the organic world. Lotka interpreted Boltzmann's view to imply that available energy could be the central concept that unified physics and biology as a quantitative physical principle of evolution. In the foreword to Boltzmann's Theoretical Physics and Philosophical Problems, S.R. de Groot noted that

Boltzmann had a tremendous admiration for Darwin and he wished to extend Darwinism from biological to cultural evolution. In fact he considered biological and cultural evolution as one and the same things. ... In short, cultural evolution was a physical process taking place in the brain. Boltzmann included ethics in the ideas which developed in this fashion ...

Awards and honours

In 1885 he became a member of the Imperial Austrian Academy of Sciences and in 1887 he became the President of the University of Graz. He was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1888 and a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1899.[1] The following are named in his honour:

- List of things named after Ludwig Boltzmann - 12 streets in Austria and Germany are named after him

- Boltzmann's Energy Equipartition theorem

- Boltzmann brain

- Boltzmann machine

- Boltzmann equation

- Lattice Boltzmann methods, used in computational fluid dynamics

- Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft

- Boltzmann Medal

- Boltzmann (crater)

References

- ^ a b "Fellows of the Royal Society". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16.

- ^ Južnič, Stanislav (December 2001). "Ludwig Boltzmann in prva študentka fizike in matematike slovenskega rodu". Kvarkadabra.net (in Slovenian) (12). Retrieved 17 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Paul Ehrenfest (1880–1933) along with Nernst[,] Arrhenius, and Meitner must be considered among Boltzmann's most outstanding students."—Jäger, Gustav; Nabl, Josef; Meyer, Stephan (April 1999). "Three Assistants on Boltzmann". Synthese. 119 (1–2): 69–84. doi:10.1023/A:1005239104047.

- ^ "Walther Hermann Nernst visited lectures by Ludwig Boltzmann"

- ^ Max Planck (1896). "Gegen die neure Energetik". Annalen der Physik. 57: 72–78. Bibcode:1896AnP...293...72P. doi:10.1002/andp.18962930107.

- ^ Ostwald offered to Boltzmann the professorial chair of physics which was vacated upon the death of Gustav Heinrich Wiedemann.

- ^ Upon Boltzmann's resignation, Theodor des Coudres became his successor in the professorial chair at Leipzig.

- ^ Ruth Lewin Sime (May 13, 1997). "Lise Meitner, A Life in Physics". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Boltzmann, Ludwig (1995). "Conclusions". In Blackmore, John T. (ed.). Ludwig Boltzmann: His Later Life and Philosophy, 1900-1906. Vol. 2. Springer. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-0-7923-3464-4.

- ^ Upon Boltzmann's death, Friedrich ("Fritz") Hasenöhrl became his successor in the professorial chair of physics at Vienna.

- ^ "Eureka! Science's greatest thinkers and their key breakthroughs", Hazel Muir, p.152, ISBN 1780873255

- ^ Max Planck, p. 119.

- ^ The concept of entropy was introduced by Rudolf Clausius in 1865. He was the first to enunciate the second law of thermodynamics by saying that "entropy always increases".

- ^ An alternative is the information entropy definition introduced in 1948 by Claude Shannon.[1] It was intended for use in communication theory, but is applicable in all areas. It reduces to Boltzmann's expression when all the probabilities are equal, but can, of course, be used when they are not. Its virtue is that it yields immediate results without resorting to factorials or Stirling's approximation. Similar formulas are found, however, as far back as the work of Boltzmann, and explicitly in Gibbs (see reference).

- ^ Pauli, Wolfgang (1973). Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-66035-0., p. 21

- ^ File:Zentralfriedhof_Vienna_-_Boltzmann.JPG

- ^ Maxwell, J. (1871). Theory of heat. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- ^ Boltzmann, L. (1974). The second law of thermodynamics. Populare Schriften, Essay 3, address to a formal meeting of the Imperial Academy of Science, 29 May 1886, reprinted in Ludwig Boltzmann, Theoretical physics and philosophical problem, S. G. Brush (Trans.). Boston: Reidel. (Original work published 1886)

- ^ Boltzmann, L. (1974). The second law of thermodynamics. p. 20

- ^ "Collier's Encyclopedia", Volume 19 Phyfe to Reni, "Physics", by David Park, p. 15

- ^ "Collier's Encyclopedia", Volume 22 Sylt to Uruguay, Thermodynamics, by Leo Peters, p. 275

Further reading

- Roman Sexl & John Blackmore (eds.), "Ludwig Boltzmann – Ausgewahlte Abhandlungen", (Ludwig Boltzmann Gesamtausgabe, Band 8), Vieweg, Braunschweig, 1982.

- John Blackmore (ed.), "Ludwig Boltzmann – His Later Life and Philosophy, 1900–1906, Book One: A Documentary History", Kluwer, 1995. ISBN 978-0-7923-3231-2

- John Blackmore, "Ludwig Boltzmann – His Later Life and Philosophy, 1900–1906, Book Two: The Philosopher", Kluwer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1995. ISBN 978-0-7923-3464-4

- John Blackmore (ed.), "Ludwig Boltzmann – Troubled Genius as Philosopher", in Synthese, Volume 119, Nos. 1 & 2, 1999, pp. 1–232.

- Blundell, Stephen; Blundell, Katherine M. (2006). Concepts in Thermal Physics. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-19-856769-1.

- Brush, Stephen G. (ed. & tr.), Boltzmann, Lectures on Gas Theory, Berkeley, California: U. of California Press, 1964

- Brush, Stephen G. (ed.), Kinetic Theory, New York: Pergamon Press, 1965

- Cercignani, Carlo (1998). Ludwig Boltzmann: The Man Who Trusted Atoms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198501541.

- Boltzmann, Ludwig Boltzmann – Leben und Briefe, ed., Walter Hoeflechner, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. Graz, Oesterreich, 1994

- Brush, Stephen G. (1970). "Boltzmann". In Charles Coulston Gillispie (ed.) (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-16962-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Brush, Stephen G. (1986). The Kind of Motion We Call Heat: A History of the Kinetic Theory of Gases. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 0-7204-0370-7.

- Everdell, William R (1988). "The Problem of Continuity and the Origins of Modernism: 1870–1913". History of European Ideas. 9 (5): 531–552. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(88)90001-0.

- Everdell, William R (1997). The First Moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- P. Ehrenfest & T. Ehrenfest (1911) "Begriffliche Grundlagen der statistischen Auffassung in der Mechanik", in Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften mit Einschluß ihrer Anwendungen Band IV, 2. Teil ( F. Klein and C. Müller (eds.). Leipzig: Teubner, pp. 3–90. Translated as The Conceptual Foundations of the Statistical Approach in Mechanics. New York: Cornell University Press, 1959. ISBN 0-486-49504-3

- Klein, Martin J. (1973). "The Development of Boltzmann's Statistical Ideas". In E.G.D. Cohen and W. Thirring (eds) (ed.). The Boltzmann Equation: Theory and Applications. Acta physica Austriaca Suppl. 10. Wien: Springer. pp. 53–106. ISBN 0-387-81137-0.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Tolman, Richard C. (1938). The Principles of Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University Press. Reprinted: Dover (1979). ISBN 0-486-63896-0

- Gibbs, Josiah Willard (1902). Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, developed with especial reference to the rational foundation of thermodynamics. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Lindley, David (2001). Boltzmann's Atom: The Great Debate That Launched A Revolution In Physics. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-85186-5.

- Lotka, A. J. (1922). "Contribution to the Energetics of Evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 8 (6): 147–51. Bibcode:1922PNAS....8..147L. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.6.147. PMC 1085052. PMID 16576642.

- Bronowski, Jacob (1974). "World Within World". The Ascent Of Man. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-316-10930-7.

- Meyer, Stefan (1904). Festschrift Ludwig Boltzmann gewidmet zum sechzigsten Geburtstage 20. Februar 1904 (in German). J. A. Barth.

- Planck, Max (1914). The Theory of Heat Radiation. P. Blakiston Son & Co. English translation by Morton Masius of the 2nd ed. of Waermestrahlung. Reprinted by Dover (1959) & (1991). ISBN 0-486-66811-8

External links

- Uffink, Jos (2004). "Boltzmann's Work in Statistical Physics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ludwig Boltzmann", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- "Ludwig Boltzmann," Universität Wien (German).

- Ruth Lewin Sime, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics Chapter One: Girlhood in Vienna gives Lise Meitner's account of Boltzmann's teaching and career.

- E.G.D. Cohen, 1996, "Boltzmann and Statistical Mechanics."

- Eftekhari, Ali, "Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906)." Discusses Boltzmann's philosophical opinions, with numerous quotes.

- Rajasekar, S.; Athavan, N. (2006-09-07). "Ludwig Edward Boltzmann". arXiv:physics/0609047.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help) - Ludwig Boltzmann at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang (ed.). "Boltzmann, Ludwig (1844–1906)". ScienceWorld.

- Ludwig Boltzmann at Find a Grave

- Jacob Bronowski from "The Ascent Of Man" on YouTube

- Author profile in the database zbMATH

- 1844 births

- 1906 deaths

- Scientists from Vienna

- Austrian physicists

- Thermodynamicists

- Scientists who committed suicide

- Mathematicians who committed suicide

- Burials at the Zentralfriedhof

- University of Vienna alumni

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Corresponding Members of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- People with bipolar disorder

- Suicides by hanging in Italy

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Mathematical physicists

- Theoretical physicists