Marine Current Turbines

This article contains promotional content. (May 2020) |

This article contains wording that promotes the subject through exaggeration of unnoteworthy facts. (May 2020) |

| Industry | Renewables : manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Founded | 2000 |

| Founder | Peter Fraenkel |

| Defunct | 2015 |

| Fate | Acquired by Atlantis Resources |

| Headquarters | , |

| Products | tidal stream generators |

| Parent |

|

| Website | www |

Marine Current Turbines Ltd (MCT), was a United Kingdom-based company that developed tidal stream generators, most notably the 1.2 MW SeaGen turbine. The company was bought by the German automation company, Siemens in 2012, who later sold the company to Atlantis Resources in 2015.

History

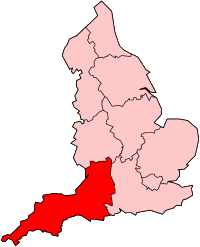

[edit]MCT was founded in 2000 to develop ideas of tidal power developed by Peter Fraenkel, who had previously been a founder partner of IT Power,[2] a consultancy established to further the development of sustainable energy technologies. The company was based in Bristol and employed 15 people in 2007.[3]

By 2003, MCT had installed a 300 kW experimental tidal turbine 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) northeast of Lynmouth, Devon and by 2008 they had a 1.2 MW turbine, SeaGen, in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland which was able to feed electricity into the National Grid.[4]

They had contracts to install a full tidal farm in the Skerries, off northwest Wales, and projects in the Bay of Fundy, Nova Scotia and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, however these projects never progressed.

In February 2012, Siemens acquired a majority share in the company, raising its holding from 45% to over 90%.[1] MCT was wholly owned by Siemens, as part of the Hydro and Ocean Business, before being transferred to the Renewables business, and finally divested to Atlantis Resources in 2015 who effectively shut the company down.[5][6]

Technology

[edit]The technology developed by MCT works much the same as a submerged windmill, driven by the flow of water rather than air. Tidal flows are more predictable than air flows both in time and maximum velocity, therefore, it is possible to bring designs closer to the theoretical maximum. The turbines have a patented feature by which they can take advantage of the reversal of flow every 6 hours and generate on both flow and ebb of the tide. The tips of the blades are placed well below the surface so they will not be a danger to shipping or be vulnerable to storms.[citation needed]

Because the blades move relatively slowly (15 rpm)[3] and there are only two, it is unlikely that there will be adverse environmental impacts on fish or other aquatic life. A monitoring project has been set up in the Strangford Lough project to confirm this.[7]

Two approaches were being developed by MCT, one for relatively shallow waters, up to 30 metres (98 ft), and the other for deeper waters. In shallow waters, the turbines are suspended on a tower which extends above the water surface and enables the turbines to be lifted clear off the water for maintenance purposes. But since the number of sites around the world where this is possible is finite, they also started developing a fully submersed system which will take advantage of larger scale, but will also be able to be brought to the surface for maintenance.[8]

Proof of concept testing

[edit]Prior to setting up MCT, Fraenkel developed and tested a proof of concept tidal stream turbine in the Corran Narrows of Loch Linnhe, Scotland.[9][10] This turbine was 3.5 m diameter (9.6 m² swept area), with two fixed pitch blades, and was capable of generating 15 kW in a 2.25 m/s current.[11] It was tested in 1994-95, in a project primarily funded by Scottish Nuclear. The turbine and submerged generator were supported below a moored catamaran barge by a vertical strut. As the world's first tidal stream turbine, it was donated to the National Museum of Scotland in 2010.[12]

SeaFlow

[edit]

The SeaFlow project involved building a full-size prototype capable of producing 300 kW. This was installed off the Devon coast near Lynmouth in May 2003.[4] The turbine was supported via a collar around on a single monopile, meaning it could be raised out of the water for maintenance. The turbine again had a two-bladed horizontal-axis rotor, but increased to 11 m diameter (95 m² swept area). It had 180° pitch control on the blades to allow generation on the ebb and flood tides. This was connected via a gearbox to the 450 kVA squirrel cage induction generator.[13]

The 80 t foundation, a steel monopile of 2.1 m diameter and 42.5 m in length, was installed by a jack-up barge in June 2003. The turbine was commissioned by August 2003.[13]

Planning permission was granted in March 2000 by Exmoor National Park Authority to connect the turbine to the national grid, however it was not ever connected to the gird. The peak electrical power output was just under 300 kW.[13]

SeaGen

[edit]SeaGen was a full-scale tidal stream power station that first produced electricity on 14 July 2008.[4] However, subsequently a computer problem caused damage to one of the rotors and procuring a replacement took until the end of October 2008.[14] SeaGen was able to operate using just its good rotor through the summer of 2008 and that rotor was operated at full rated power of 600 kW for many hours.[citation needed] After replacement of the damaged rotor SeaGen delivered its full rated power of 1.2MW for the first time on 18 December 2008[15] - believed to be the first time a "wet renewable energy system" has delivered in excess of 1MW.[citation needed]

Skerries Tidal Stream Array

[edit]In a proposed joint project with RWE Npower Renewables, seven of the SeaGen generators, producing about 10 MW at peak, were to be installed off the Skerries, a patch of very fast-moving water off Anglesey in northwest Wales.[16] An environmental consent application was submitted to the Welsh Government in March 2011.[17] The scheme was shelved in September 2014 by MCT/Siemens.[18] There was speculation the project would be revived after Atlantis Resources bought MCT,[18] but there has been no progress since. SIMEC Atlantis Energy returned the lease agreement for the site to the Crown Estate in 2016.[19]

Kyle Rhea Tidal Stream Array

[edit]MCT, through a subsidiary Sea Generation (Kyle Rhea) Ltd., also planned to develop an array in the Kyle Rhea Narrows between the Isle of Skye and the Scottish Mainland, located just to the north of the Kylereah to Glenelg ferry route.[20][21] The plan was to install four SeaGen turbines, similar to that installed in Strangford Lough, although potentially rated at up to 2 MW each for a total array of 8 MW. The company secured an agreement to lease the seabed from the Crown Estate in 2011, although this was later returned by SIMEC Atlantis Energy in 2016.[22][19] An environmental impact assessment for the project was produced by Royal Haskoning, and an application was submitted to Marine Scotland, however this was later withdrawn.[21] MCT was awarded €18.4 million of funding through the New Entrants Reserve (NER 300) scheme of the European Union Emissions Trading System, which was transferred to the MeyGen project in 2015 after the acquisition of MCT by Atlantis.

Canada

[edit]An agreement was made with Canada's Maritime Tidal Energy Corporation (MTEC) in 2007 to develop tidal resources in the Bay of Fundy.[23] With a tidal range exceeding 15 metres (49 ft), and flows of up to 14 kilometres per hour (8.7 mph), this area has long been favoured as the most promising source of tidal power and the newer tidal flow concepts mean that the associated environmental and shipping problems of barrage schemes are no longer prohibitive. MTEC concluded that MCT had the most proven technology of the companies evaluated.[24]

On the west coast, they also agreed to install at least three 1.2 MW turbines in the Campbell River in British Columbia as a first step in developing tidal farms in that river and other tidal waters.

Neither of these projects in Canada were completed, however.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Louise Downing; Stefan Nicola (17 February 2012), "Siemens to Buy U.K. Tidal Turbine Maker in Next Few Weeks", www.bloomberg.com, Bloomberg LP

- ^ IT Power website

- ^ a b "Seagen Tidal Power Installation". Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Brittany Sauser (15 August 2008). "Tidal Power Comes to Market. A large-scale tidal-power unit has started up in Northern Ireland". Technology Review Inc., Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ^ "Today's News | London Stock Exchange". Archived from the original on 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Siemens offloads Marine Current Turbines to Atlantis Resources". 29 April 2015.

- ^ Erwin, David G (May 2007). Environmental monitoring, liaison and consultation concerning the MCT Strangford Lough Turbine.concerning the MCT Strangford Lough Turbi (PDF). All Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2009 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Technology - Deep water". Marine Current Turbines. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Fraenkel, Peter (19 October 2010). Practical tidal turbine design considerations: a review of technical alternatives and key design decisions leading to the development of the SeaGen 1.2MW tidal turbine. Ocean Power Fluid Machinery Seminar, London. Institution of Mechanical Engineers – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Pearce, Fred (20 June 1998). "Catching the tide". New Scientist. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Fraenkel, P. L. (1 February 2002). "Power from marine currents". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy. 216 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1243/095765002760024782. ISSN 0957-6509.

- ^ "Turbine system". National Museums Scotland (Collections database). Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Thake, Jeremy; Clutterbuck, Peter; Bard, Jochen; Haske, Dirk (January 2005). SEAFLOW project synopses (Report). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17965.20961. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Marine Current Turbines (25 July 2008). "News - Delay in commissioning one of SeaGen's rotors". Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Tidal energy system on full power". BC News. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Boettcher, Daniel (20 October 2011). "Wave and tidal power get more support". BBC News. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Crown Estate lease agreed for Anglesey tidal power farm". BBC. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b Kelsey, Chris (1 May 2015). "£70m Skerries tidal project gets second lease of life as Atlantis buys MCT". Wales Online. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Atlantis drops tidal energy project at Kylerhea in Skye". BBC News. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Bristol firm plans Scotland's first tidal energy farm". BBC News. 2 December 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Kyle Rhea Tidal Stream Array Project | Tethys". tethys.pnnl.gov. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Green light for £40m tidal energy scheme off Skye". The Herald. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Agreement with MTEC

- ^ Arrangement with Maritime Tidal Energy Corporation Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Wang Jifeng, Mueller Norbert (2011). "Numerical investigation on composite material marinecurrent turbine using CFD". Cent. Eur. J. Eng. 1 (4): 334–340. Bibcode:2011CEJE....1..334W. doi:10.2478/s13531-011-0033-6.