Pair bond

In biology, a pair bond is the strong affinity that develops in some species between a mating pair, often leading to the production and rearing of young and potentially a lifelong bond. Pair-bonding is a term coined in the 1940s[1] that is frequently used in sociobiology and evolutionary biology circles. The term often implies either a lifelong socially monogamous relationship or a stage of mating interaction in socially monogamous species. It is sometimes used in reference to human relationships.

Varieties

[edit]

According to evolutionary psychologists David P. Barash and Judith Lipton, from their 2001 book The Myth of Monogamy, there are several varieties of pair bonds:[2]

- Short-term pair-bond: a transient mating or associations

- Long-term pair-bond: bonded for a significant portion of the life cycle of that pair

- Lifelong pair-bond: mated for life

- Social pair-bond: attachments for territorial or social reasons

- Clandestine pair-bond: quick extra-pair copulations

- Dynamic pair-bond: e.g. gibbon mating systems being analogous to "divorce"

Examples

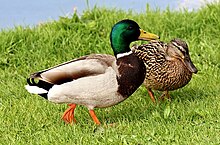

[edit]Birds

[edit]Close to ninety percent[3] of known avian species are monogamous, compared to five percent of known mammalian species. The majority of monogamous avians form long-term pair bonds which typically result in seasonal mating: these species breed with a single partner, raise their young, and then pair up with a new mate to repeat the cycle during the next season. Some avians such as swans, bald eagles, California condors, and the Atlantic Puffin are not only monogamous, but also form lifelong pair bonds.[4]

When discussing the social life of the bank swallow, Lipton and Barash state:[2]

For about four days immediately prior to egg-laying, when copulations lead to fertilization, the male bank swallow is very busy, attentively guarding his female. Before this time, as well as after—that is, when her eggs are not ripe, and again after his genes are safely tucked away inside the shells—he goes seeking extra-pair copulations with the mates of other males…who, of course, are busy with defensive mate-guarding of their own.

In various species, males provide parental care and females mate with multiple males. For example, recent studies show that extra-pair copulation frequently occurs in monogamous birds in which a "social" father provides intensive care for its "social" offspring.[5] Furthermore, it was observed that newly formed pair bonds in biparental plovers were comparatively weaker than those in uniparental plovers.[6]

Fish

[edit]A University of Florida scientist reports that male sand gobies work harder at building nests and taking care of eggs when females are present – the first time such "courtship parental care" has been documented in any species.[7]

In the cichlid species Tropheus moorii, a male and female will form a temporary monogamous pair bond and spawn; after which, the female leaves to mouthbrood the eggs on her own. T. moorii broods exhibit genetic monogamy (all eggs in a brood are fertilized by a single male).[8] Another mouth brooding cichlid – the Lake Tanganyika cichlid (Xenotilapia rotundiventralis) has been shown that mating pairs maintain pair bonds at least until the shift of young from female to male.[9] More recently the Australian Murray cod has been seen maintaining pair bonds over 3 years.[10]

Pair bonding may also have non-reproductive benefits, such as assisted resource defense.[11] Recent study comparing two species of butterflyfishes, C. baronessa and C. lunulatus, indicate increase in food and energy reserves compared to individual fish.[12]

Mammals

[edit]Monogamous voles (such as prairie voles) have significantly greater density and distribution of vasopressin receptors in their brain when compared to polygamous voles. These differences are located in the ventral forebrain and the dopamine-mediated reward pathway.

Peptide arginine vasopressin (AVP), dopamine, and oxytocin act in this region to coordinate rewarding activities such as mating, and regulate selective affiliation. These species-specific differences have shown to correlate with social behaviors, and in monogamous prairie voles are important for facilitation of pair bonding. When compared to montane voles, which are polygamous, monogamous prairie voles appear to have more of these AVP and oxytocin neurotransmitter receptors. It is important that these receptors are in the reward centers of the brain because that could lead to a conditioned partner preference in the prairie vole compared to the montane vole which would explain why the prairie vole forms pair bonds and the montane vole does not.[3][13]

As noted above, different species of voles vary in their sexual behavior, and these differences correlate with expression levels of vasopressin receptors in reward areas of the brain. Scientists were able to change adult male montane voles' behavior to resemble that of monogamous prairie voles in experiments in which vasopressin receptors were introduced into the brain of male montane voles.[citation needed]

Humans

[edit]

Humans can experience all of the above-mentioned varieties of pair bonds. These bonds can be temporary or last a lifetime.[14] They also engage in social pair bonding, where two form a close relationship that does not involve sex.[15] Like in other vertebrates, pair bonds are created by a combination of social interaction and biological factors including neurotransmitters like oxytocin, vasopressin, and dopamine.[15][16]

Pair bonds are a biological phenomenon and are not equivalent to the human social institution of marriage. Married couples are not necessarily pair bonded. Marriage may be a consequence of pair bonding and vice versa. One of the functions of romantic love is pair bonding.[17][15]

See also

[edit]- Affectional bond

- Attachment theory

- Animal sexuality

- Breeding pair

- Human bonding

- r/K selection theory

References

[edit]- ^ "Pair-bond". Home : Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford English Dictionary. 2005.

- ^ a b Barash D, Lipton J (2001). The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805071368.

- ^ a b Young LJ (2003). "The Neural Basis of Pair Bonding in a Monogamous Species: A Model for Understanding the Biological Basis of Human Behavior". In Wachter KW, Bulatao RA (eds.). Offspring: Human Fertility Behavior in Biodemographic Perspective. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-08718-6. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018 – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Berger M (10 February 2012). "Till Death do them Part: 8 Birds that Mate for Life". National Audubon Society. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ Wakano JY, Ihara Y (August 2005). "Evolution of male parental care and female multiple mating: game-theoretical and two-locus diploid models". The American Naturalist. 166 (2): E32–44. doi:10.1086/431252. PMID 16032569. S2CID 23771617.; Lay summary in: "New Study Explores The Evolution Of Male Parental Care And Female Multiple Mating". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05.

- ^ Parra, Jorge E.; Beltrán, Marcela; Zefania, Sama; Dos Remedios, Natalie; Székely, Tamás (2014-04-01). "Experimental assessment of mating opportunities in three shorebird species" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 90: 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.12.030. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 15727544.

- ^ Pampoulie C, Lindström K, St Mary CM (March 2004). "Have your cake and eat it too: male sand gobies show more parental care in the presence of female partners". Behavioral Ecology. 15 (2): 199–204. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg107.; Lay summary in: "For A Male Sand Goby, Playing 'Mr. Mom' Is Key To Female's Heart". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ Steinwender B, Koblmüller S, Sefc KM (February 2012). "Concordant female mate preferences in the cichlid fish Tropheus moorii". Hydrobiologia. 682 (1): 121–130. doi:10.1007/s10750-011-0766-5. PMC 3841713. PMID 24293682.

- ^ Takahashi T, Ochi H, Kohda M, Hori M (June 2012). "Invisible pair bonds detected by molecular analyses". Biology Letters. 8 (3): 355–357. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.1006. PMC 3367736. PMID 22114323.

- ^ Couch AJ, Dyer F, Lintermans M (2020). "Multi-year pair-bonding in Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii)". PeerJ. 8: e10460. doi:10.7717/peerj.10460. PMC 7733648. PMID 33354425.

- ^ Bales KL, Ardekani CS, Baxter A, Karaskiewicz CL, Kuske JX, Lau AR, et al. (November 2021). "What is a pair bond?". Hormones and Behavior. 136: 105062. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105062. PMID 34601430. S2CID 238234968.

- ^ Nowicki JP, Walker SP, Coker DJ, Hoey AS, Nicolet KJ, Pratchett MS (April 2018). "Pair bond endurance promotes cooperative food defense and inhibits conflict in coral reef butterflyfish". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 6295. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.6295N. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24412-0. PMC 5908845. PMID 29674741.

- ^ Lim MM, Wang Z, Olazábal DE, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ (June 2004). "Enhanced partner preference in a promiscuous species by manipulating the expression of a single gene". Nature. 429 (6993): 754–757. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..754L. doi:10.1038/nature02539. PMID 15201909. S2CID 4340500.

- ^ Overdorff DJ, Tecot SR (2006). "Social Pair-Bonding and Resource Defense in Wild Red-Bellied Lemurs (Eulemur rubriventer)". Lemurs. Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospect. pp. 235–254. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-34586-4_11. ISBN 978-0-387-34585-7.

- ^ a b c Fuentes A (9 May 2012). "On Marriage and Pair Bonds". Psychology Today. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Garcia C (May 2019). The Role of Oxytocin on Social Behavior Associated with the Formation of a Social Pair-Bond in the Socially Monogamous Convict Cichlid (Amatitlania nigrofasciata) (PhD thesis). Winthrop University.

- ^ Bode A, Kushnick G (2021). "Proximate and Ultimate Perspectives on Romantic Love". Frontiers in Psychology. 12: 573123. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.573123. PMC 8074860. PMID 33912094.