Melissa (song)

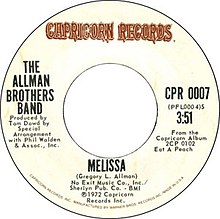

| "Melissa" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by The Allman Brothers Band | ||||

| from the album Eat a Peach | ||||

| A-side | "Blue Sky" | |||

| Released | August 1972 | |||

| Recorded | December 9, 1971 at Criteria Studios, Miami, Florida | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 3:56 | |||

| Label | Capricorn Records | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Gregg Allman | |||

| Producer(s) | Tom Dowd | |||

| The Allman Brothers Band singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Melissa" is a song by American rock band the Allman Brothers Band, released in August 1972 as the second single from the group's third studio album, Eat a Peach. The song was written by vocalist Gregg Allman long before the founding of the group. It was first written in 1967, and two demo versions from those years exists, including a version cut by the 31st of February, a band that featured Butch Trucks, the Allman Brothers' later drummer. Allman sold the publishing rights later that year, but they were reacquired by manager Phil Walden in 1972.

The song's title is frequently referred to incorrectly as "Sweet Melissa" due to the lyric being sung at the end of each of the first two choruses.[1]

The version on Eat a Peach was recorded in tribute to Duane Allman, who considered the song among his brother's best and a personal favorite. He died in a motorcycle accident three months before its most famous rendition was recorded.

Background

Gregg Allman penned the song in late 1967.[2] He had previously struggled to create any songs with substance, and "Melissa" was among the first that survived after nearly 300 attempts to write a song he deemed good enough. Staying at the Evergreen Motel in Pensacola, Florida, he picked up Duane's guitar which was tuned to open E and immediately felt inspired by the natural tuning.[2] Words came naturally, but he stumbled on the name of the love interest. The song's namesake was almost settled as Delilah before Melissa came to Allman at a grocery store where he was buying milk late one night, as he told the story in his memoir, My Cross to Bear:

It was my turn to get the coffee and juice for everyone, and I went to this twenty-four-hour grocery store, one of the few in town. There were two people at the cash registers, but only one other customer besides myself. She was an older Spanish lady, wearing the colorful shawls, with her hair all stacked up on her head. And she had what seemed to be her granddaughter with her, who was at the age when kids discover they have legs that will run. She was jumping and dancing; she looked like a little puppet. I went around getting my stuff, and at one point she was the next aisle over, and I heard her little feet run all the way down the aisle. And the woman said, "No, wait, Melissa. Come back—don’t run away, Melissa!" I went, "Sweet Melissa." I could've gone over there and kissed that woman. As a matter of fact, we came down and met each other at the end of the aisle, and I looked at her and said, "Thank you so much." She probably went straight home and said, "I met a crazy man at the fucking grocery."[3]

Allman rushed home and incorporated the name into the partially completed song, later introducing it to his brother: "[I] played it for my brother and he said, 'It's pretty good—for a love song. It ain't rock and roll that makes me move my ass.' He could be tough that way."[4] The duo produced a demo recording of "Melissa" that later surfaced on One More Try, a compilation of outtakes released thirty years later.[4] In 1968, the duo recorded it during a demo session with the 31st of February, a band that featured Butch Trucks, the Allman Brothers' later drummer. That version is thought to have featured the debut recorded slide guitar performance from Duane Allman, and the entire session was later compiled into Duane & Greg Allman, released in 1972.[4] Gregg Allman sold the publishing rights to "Melissa", as well as the Martin Luther King, Jr. tribute "God Rest His Soul", to producer Steve Alaimo for $250 shortly thereafter. He had been tied up in Los Angeles, contractually bound by Liberty Records (who had previously issued albums by the Allmans' first band, the Hour Glass), and used the money to buy an airplane ticket to fly back.[4]

When Duane Allman was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1971, his brother performed the song at his funeral, as he had grown to like the song over the years. Gregg Allman commented that it "didn’t sit right" that he used one of his brother's old guitars for the performance, but he nonetheless got through it; he called it "my brother’s favorite song that I ever wrote."[5] Both because he did not own the rights and found it "too soft" for the band’s repertoire, he never mentioned the song to the members of the Allman Brothers Band.[6] Following Duane's death, manager Phil Walden arranged to buy back the publishing rights in order to record the song for Eat a Peach, the band’s third studio album. Gregg brought it to the studio the day following his birthday and the band recorded it that afternoon at Criteria Studios in Miami, Florida. They felt it lacked a compelling instrumental backing element so guitarist Dickey Betts created the song’s lead guitar line. [6]

In popular culture

"Melissa" has enjoyed renewed popularity in the 2000s due to its feature in a commercial for Cingular/AT&T Wireless cell phone company and the use of it in a scene in Brokeback Mountain. The song was also featured in the Costner/Houston slow dance scene in the bar in the film "The Bodyguard." It was prominently featured in the 2005 film House of D, performed by both the Allman Brothers and Erykah Badu.

Notes

References

- Paul, Alan (2014). One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1250040497.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allman, Gregg; Light, Alan (2012). My Cross to Bear. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0062112033.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)