Metoprolol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛˈtoʊproʊlɑːl/, /mɛtoʊˈproʊlɑːl/ |

| Trade names | Lopressor, Metolar XR, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682864 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, IV |

| Drug class | Beta blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% (single dose)[1] 70% (repeated administration)[2] |

| Protein binding | 12% |

| Metabolism | Liver via CYP2D6, CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 3–7 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.051.952 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H25NO3 |

| Molar mass | 267.369 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 120 °C (248 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Metoprolol, marketed under the tradename Lopressor among others, is a medication of the selective β1 receptor blocker type.[3] It is used to treat high blood pressure, chest pain due to poor blood flow to the heart, and a number of conditions involving an abnormally fast heart rate.[3] It is also used to prevent further heart problems after myocardial infarction and to prevent headaches in those with migraines.[3]

Metoprolol is sold in formulations that can be taken by mouth or given intravenously.[3] The medication is often taken twice a day.[3] The extended-release formulation is taken once per day.[3] Metoprolol may be combined with hydrochlorothiazide (a diuretic) in a single tablet.[3]

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, feeling tired, feeling faint, and abdominal discomfort.[3] Large doses may cause serious toxicity.[4][5] Risk in pregnancy has not been ruled out.[3][6] It appears to be safe in breastfeeding.[7] Greater care is required with use in those with liver problems or asthma.[3] Stopping this drug should be done slowly to decrease the risk of further health problems.[3]

Metoprolol was first made in 1969.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[9] It is available as a generic drug.[3] In 2013, metoprolol was the 19th-most prescribed medication in the United States.[10]

Medical uses

Metoprolol is used for a number of conditions, including hypertension, angina, acute myocardial infarction, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and prevention of migraine headaches.[11]

- Treatment of heart failure[12]

- Vasovagal syncope[13][14]

- Adjunct in treatment of hyperthyroidism[15]

- Long QT syndrome, especially for patients with asthma, as metoprolol's β1 selectivity tends to interfere less with asthma drugs, which are often β2-adrenergic receptor-agonist drugs[citation needed]

- Prevention of relapse into atrial fibrillation (controlled-release/extended-release form)[16]

Due to its selectivity in blocking the beta1 receptors in the heart, metoprolol is also prescribed for off-label use in performance anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and other anxiety disorders.

Available forms

Metoprolol is sold in formulations that can be taken by mouth or given intravenously.[3] The medication is often taken twice a day.[3] The extended-release formulation is taken once per day.[3] Metoprolol may be combined with hydrochlorothiazide (a diuretic) in a single tablet.[3]

Adverse effects

Side effects, especially with higher doses, include dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, diarrhea, unusual dreams, trouble sleeping, depression, and vision problems. Metoprolol may also reduce blood flow to the hands or feet, causing them to feel numb and cold; smoking may worsen this effect.[17] Due to the high penetration across the blood-brain barrier, lipophilic beta blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol are more likely than other less lipophilic beta blockers to cause sleep disturbances such as insomnia and vivid dreams and nightmares.[18]

Serious side effects that are advised to be reported immediately include symptoms of bradycardia (resting heart rate slower than 60 beats per minute), persistent symptoms of dizziness, fainting and unusual fatigue, bluish discoloration of the fingers and toes, numbness/tingling/swelling of the hands or feet, sexual dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, hair loss, mental/mood changes, depression, breathing difficulty, cough, dyslipidemia and increased thirst. Consuming alcohol while taking metoprolol may cause mild body rashes and is not advised.[17]

Precautions

Metoprolol may worsen the symptoms of heart failure in some patients, who may experience chest pain or discomfort, dilated neck veins, extreme fatigue, irregular breathing, an irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath, swelling of the face, fingers, feet, or lower legs, weight gain, or wheezing.[19]

This medicine may cause changes in blood sugar levels or cover up signs of low blood sugar, such as a rapid pulse rate.[19] It also may cause some people to become less alert than they are normally, making it dangerous for them to drive or use machines.[19]

Greater care is required with use in those with liver problems or asthma.[3] Stopping this drug should be done slowly to decrease the risk of further health problems.[3]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Risk for the fetus has not been ruled out, per being rated pregnancy category C in the United States.[3][6] Metoprolol is category C in Australia, meaning that it may be suspected of causing harmful effects on the human fetus (but no malformations).[6] It appears to be safe in breastfeeding.[7]

Overdose

Excessive doses of metoprolol can cause severe hypotension, bradycardia, metabolic acidosis, seizures, and cardiorespiratory arrest. Blood or plasma concentrations may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of overdose or poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma levels are usually less than 200 μg/l during therapeutic administration, but can range from 1–20 mg/l in overdose victims.[20][21][22]

Pharmacology

General pharmacological principles of metoprolol:[citation needed]

- beta-1 selective

- moderately lipophilic

- without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity

- with weak membrane stabilizing activity

- decreases heart rate, contractility, and cardiac output, therefore decreasing blood pressure

Mechanism of action

Metoprolol blocks β1 adrenergic receptors in heart muscle cells, thereby decreasing the slope of phase 4 in the nodal action potential (reducing Na+ uptake) and prolonging repolarization of phase 3 (slowing down K+ release).[23] It also suppresses the norepinephrine-induced increase in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ leak and the spontaneous SR Ca2+ release, which are the major triggers for atrial fibrillation.[23]

Pharmacokinetics

Metoprolol has a short half-life of 3 to 7 hours, so is taken at least twice daily or as a slow-release preparation.

It undergoes α-hydroxylation and O-demethylation as a substrate of the cytochrome liver enzymes CYP2D6[24][25] and a small percentage by CYP3A4, resulting in inactive metabolites.

Chemistry

Metoprolol has a very low melting point; around 120 °C (248 °F) for the tartrate, and around 136 °C (277 °F) for the succinate. Because of this, metoprolol is always manufactured in a salt-based solution, as drugs with low melting points are difficult to work with in a manufacturing environment. The free base exists as a waxy white solid, and the tartrate salt is finer crystalline material.[citation needed]

The active substance metoprolol is employed either as metoprolol succinate or as metoprolol tartrate (where 100 mg metoprolol tartrate corresponds to 95 mg metoprolol succinate). The tartrate is an immediate-release formulation and the succinate is an extended-release formulation.[26]

Stereochemistry

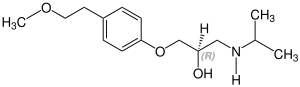

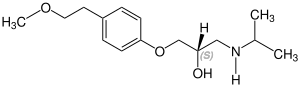

Metoprolol contains a stereocenter and consists of two enantiomers. This is a racemate, i.e. a 1:1 mixture of (R)- and the (S)-form:[27]

| Enantiomers of metoprolol | |

|---|---|

CAS-Nummer: 81024-43-3 |

CAS-Nummer: 81024-42-2 |

History

Metoprolol was first made in 1969.[8]

Society and culture

Metoprolol is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[9] It is available as a generic drug.[3] In 2013, metoprolol was the 19th-most prescribed medication in the United States.[28]

Legal status

Within the UK metoprolol is classified as a prescription-only drug in the beta blocker class and is regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The MHRA is a government body set up in 2003 and is responsible for regulating medicines, medical devices, and equipment used in healthcare. The MHRA acknowledges that no product is completely risk free but takes into account research and evidence to ensure that any risks associated are minimal.[29]

The use of beta blockers such as metoprolol was approved in the US by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) in 1967. The FDA has approved beta blockers for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, migraines, and others. Prescribers may choose to prescribe beta blockers for other treatments if there is just cause even though it is not approved by the FDA. Drug manufacturers, however, are unable to advertise beta blockers for other purposes that have not been approved by the FDA. Since the FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine after the drug has been approved, it is legal to prescribe beta blockers for other treatments such as performance anxiety.[30]

Legislation

The MHRA granted the Intas Pharmaceuticals Limited Marketing Authorisation (licences) for metoprolol tartrate (50mg and 100mg tablets) for medicinal prescription only on September 23rd 2011; this was after it was established that there was no new or unexpected safety concerns and that the benefits of metoprolol tartrate were greater than the risks. Metoprolol tartrate is a generic version of Lopressor, which was licensed and authorised on June 6th 1997 to Novartis Pharmaceuticals.[31]

In sport

Metoprolol is a beta blocker and is banned by the world anti-doping agency in some sports. Beta blockers can be used to reduce heart rate and minimize tremors, which can enhance performance in sports such as archery.[32] All beta blockers are banned during and out of competition for archery and shooting.[33] In some sports such as all forms of billiards, darts, and golf, beta blockers are banned during competition only. Furthermore, any form of beta blocker is banned within riflery competitions by the National Collegiate Athletic Association.[34]

To detect if beta blockers have been used trace analysis of human urine is analysed. Uncharged drugs and/or metabolites of beta blockers can be analysed by gas-chromatography-mass spectrometry in selected ion monitoring (GC-MS-SIM). However, in modern times it is increasingly difficult to detect the presence of beta blockers used for sports doping purposes. A disadvantage to using GC-MS-SIM is that prior knowledge of the molecular structure of the target drugs/metabolites is required. Modern times have shown a variance in structures and hence novel beta blockers can go undetected.[35]

Lawsuit

In 2012, an $11 million settlement was reached with Toprol XL (time-release formula version of metoprolol) and its generic equivalent metoprolol. The lawsuit involved the pharmaceuticals companies AstraZeneca AB, AstraZeneca LP, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, and Aktiebolaget Hassle. The claims of the lawsuit advise that the manufacturers violated antitrust and consumer protection law. Claiming that to increase profits, lower cost generic versions of Toprol XL were intentionally kept off the market. This claim was subsequently denied by the defendants.[36]

References

- ^ "Metolar 25/50 (metoprolol tartrate) tablet" (PDF). FDA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 916–919. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Metoprolol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2014-03-12. Retrieved Apr 21, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pillay (2012). Modern Medical Toxicology. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 303. ISBN 9789350259658. Archived from the original on 2017-07-07.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marx, John A. Marx (2014). "Cardiovascular Drugs". Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. Chapter 152. ISBN 1455706051.

- ^ a b c "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. p. 684. ISBN 9780781728454. Archived from the original on 2017-07-07.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Carlsson, edited by Bo (1997). Technological systems and industrial dynamics. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. p. 106. ISBN 9780792399728. Archived from the original on 2017-03-03.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Top 100 Drugs for 2013 by Units Sold". Drugs.com. February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Metoprolol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ MERIT-HF Study Group (1999). "Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF)". Lancet. 353 (9169): 2001–2007. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04440-2. PMID 10376614.

- ^ Biffi, M.; Boriani, G.; Sabbatani, P.; Bronzetti, G.; Frabetti, L.; Zannoli, R.; Branzi, A.; Magnani, B. (Mar 1997). "Malignant vasovagal syncope: a randomised trial of metoprolol and clonidine". Heart. 77 (3): 268–72. doi:10.1136/hrt.77.3.268. PMC 484696. PMID 9093048.

- ^ Zhang Q, Jin H, Wang L, Chen J, Tang C, Du J (2008). "Randomized comparison of metoprolol versus conventional treatment in preventing recurrence of vasovagal syncope in children and adolescents". Medical Science Monitor. 14 (4): CR199–CR203. PMID 18376348. Archived from the original on 2012-05-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Geffner DL, Hershman JM (July 1992). "β-Adrenergic blockade for the treatment of hyperthyroidism". The American Journal of Medicine. 93 (1): 61–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90681-Z. PMID 1352658.

- ^ Kühlkamp, V; Schirdewan, A; Stangl, K; Homberg, M; Ploch, M; Beck, OA (2000). "Use of metoprolol CR/XL to maintain sinus rhythm after conversion from persistent atrial fibrillation". J Am Coll Cardiol. 36 (1): 139–146. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00693-8. Archived from the original on 2014-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Metoprolol". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cruickshank JM (2010). "Beta-blockers and heart failure". Indian Heart Journal. 62 (2): 101–110. PMID 21180298.

- ^ a b c "Metoprolol (Oral Route) Precautions". Drug Information. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Page C, Hacket LP, Isbister GK (2009). "The use of high-dose insulin-glucose euglycemia in beta-blocker overdose: a case report". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (3): 139–143. doi:10.1007/bf03161225. PMC 3550395. PMID 19655287.

- ^ Albers S, Elshoff JP, Völker C, Richter A, Läer S (2005). "HPLC quantification of metoprolol with solid-phase extraction for the drug monitoring of pediatric patients". Biomedical Chromatography. 19 (3): 202–207. doi:10.1002/bmc.436. PMID 15484221.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1023–1025.

- ^ a b Suita, Kenji; Fujita, Takayuki; Hasegawa, Nozomi; Cai, Wenqian; Jin, Huiling; Hidaka, Yuko; Prajapati, Rajesh; Umemura, Masanari; Yokoyama, Utako (2015-07-23). "Norepinephrine-Induced Adrenergic Activation Strikingly Increased the Atrial Fibrillation Duration through β1- and α1-Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated Signaling in Mice". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): 1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133664. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4512675. PMID 26203906. Archived from the original on 2017-03-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Swaisland HC, Ranson M, Smith RP, Leadbetter J, Laight A, McKillop D, Wild MJ (2005). "Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of gefitinib with rifampicin, itraconazole and metoprolol". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 44 (10): 1067–1081. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544100-00005. PMID 16176119.

- ^ Blake, CM.; Kharasch, ED.; Schwab, M.; Nagele, P. (Sep 2013). "A meta-analysis of CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotype and metoprolol pharmacokinetics". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 94 (3): 394–9. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.96. PMC 3818912. PMID 23665868.

- ^ Cupp M (2009). "Alternatives for Metoprolol Succinate" (pdf). Pharmacist's Letter / Prescriber's Letter. 25 (250302). Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ Rote Liste Service GmbH (Hrsg.): Rote Liste 2017 – Arzneimittelverzeichnis für Deutschland (einschließlich EU-Zulassungen und bestimmter Medizinprodukte). Rote Liste Service GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, 2017, Aufl. 57, ISBN 978-3-946057-10-9, S. 200.

- ^ "Top 100 Drugs for 2013 by Units Sold". Drugs.com. February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (2018). Medicines & Medical Devices Regulation. London, pp.1-24.

- ^ Engelke, Luis C.; Ewell, Terry B. (2011) The Ethics and Legality of Beta Blockers for Performance Anxiety: What Every Educator Should Know. In: College Music Symposium, Vol. 51-52, pp. np.

- ^ MHRA (2011). PAR Metoprolol tatrate 50mg and 100mg tablets. London: MHRA.

- ^ Hughes, D. (2015). The World Anti-Doping Code in sport: Update for 2015. Australian Prescriber, 38(5), pp.167-170.

- ^ World Anti-Doping Agency (2017). Prohibited List. Montreal: WADA’s Executive Committee.

- ^ Barnes, K. and Rainbow, C. (2013). Update on Banned Substances 2013. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 5(5), pp.442-447.

- ^ Politi, L., Groppi, A. and Polettini, A. (2005). Applications of Liquid Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry in Doping Control*. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 29(1), pp.1-14.

- ^ Prnewswire.com. (2018). $11 Million Settlement Reached in Lawsuit Involving the Heart Medication, Toprol XL®, and its generic equivalent, metoprolol succinate. [online] Available at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/11-million-settlement-reached-in-lawsuit-involving-the-heart-medication-toprol-xl-and-its-generic-equivalent-metoprolol-succinate-177848501.html [Accessed 4 Mar. 2018].