Miguel de Cervantes

This article needs attention from an expert in History. The specific problem is: the referencing and therefore content are frequently suspect (given inconsistencies, large gaps); hence, an expert on Cervantes is needed to identify partially and undeclared sources, and to check content to source (removing inaccurate and repetitive content). (December 2019) |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra | |

|---|---|

![Portrait attributed to Juan de Jáuregui, original lost, but described in detail by Cervantes in the prologue of his Exemplary Novels[a][2][3][full citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Cervantes_J%C3%A1uregui.jpg/220px-Cervantes_J%C3%A1uregui.jpg) Portrait attributed to Juan de Jáuregui, original lost, but described in detail by Cervantes in the prologue of his Exemplary Novels[a][2][3][full citation needed] | |

| Born | Miguel de Cervantes 29 September 1547 (assumed) Alcalá de Henares, Spain |

| Died | 22 April 1616 (aged 68)[4] Madrid, Spain |

| Resting place | Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, Madrid |

| Occupation | Soldier, novelist, poet, playwright, accountant |

| Language | Spanish |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Notable works | Don Quixote Entremeses Novelas ejemplares |

| Spouse | Catalina de Salazar y Palacios |

| Signature | |

| |

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra[b] (/sɜːrˈvæntiːz/ sur-VAN-teez,[7] Spanish: [miˈɣel de θeɾˈβantes saaˈβeðɾa]; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS)[4] was a Spanish writer who is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. His novel Don Quixote has been translated into over 140 languages and dialects; it is, after the Bible, the most-translated book in the world.[8]

Don Quixote, a classic of Western literature, is sometimes considered both the first modern novel[9] and the best work of fiction ever written.[10] Cervantes' influence on the Spanish language has been so great that the language is often called la lengua de Cervantes ("the language of Cervantes").[11] He has also been dubbed El príncipe de los ingenios ("The Prince of Wits").[12]

In 1569, in forced exile from Castile, Cervantes moved to Rome, where he worked as chamber assistant of a cardinal. Then he enlisted as a soldier in a Spanish Navy infantry regiment and continued his military life until 1575, when he was captured by Barbary pirates. After five years of captivity, he was released on payment of a ransom by his parents and the Trinitarians, a Catholic religious order, and he returned to his family in Madrid.

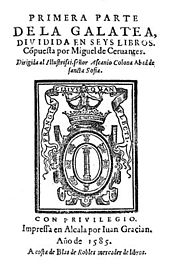

In 1585, Cervantes published La Galatea, a pastoral novel. He worked as a purchasing agent for the Spanish Armada and later as a tax collector for the government. In 1597, discrepancies in his accounts for three years previous landed him in the Crown Jail of Seville.

In 1605, Cervantes was in Valladolid when the immediate success of the first part of his Don Quixote, published in Madrid, signalled his return to the literary world. In 1607, he settled in Madrid, where he lived and worked until his death. During the last nine years of his life, Cervantes solidified his reputation as a writer, publishing Novelas ejemplares (Exemplary Novels) in 1613, Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus) in 1614, and Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses and the second part of Don Quixote in 1615. His last work, Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda), was published posthumously in 1617.

Birth and early life

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Born Miguel de Cervantes[verification needed]—the additional surname of a relative, Saavedra, would be taken later[5][6]—was a native of Alcalá de Henares, a town[13] in Castilian about 35 kilometres (22 mi) north-east from Madrid.[citation needed] The date was probably 29 September (the feast day of Saint Michael the Archangel) in 1547.[citation needed] as determined from records in the church register, given the tradition of naming a child after the feast day of his birth.[original research?][citation needed] He was baptized in Alcalá de Henares on 9 October 1547,[13][14] at the parish church of Santa María la Mayor.[citation needed] The register of baptism records contains the following:[citation needed]

Domingo, nueve días del mes de o[c]tubre año de Señor de mil e quinientos e cuarenta e siete años, fue baptizado Miguel, hijo de Rodrigo de Cervantes e su mujer doña Leonor; fueron sus compadres Juan Pardo. Baptizole el reverendo señor bachiller Serrano, cura de nuestra Señora. Testigos: Baltasar Vázquez sacristán e yo que lo baptizé y firmé de mi nombre. / El bachiller Serrano[13]

[Sunday, nine days of the month of October, year of the Lord of one thousand five hundred and forty-seven years, Miguel, son of Rodrigo de Cervantes and his wife doña [mistress] Leonor, was baptized; there were his compadres [godfather] Juan Pardo. Baptizole [Baptizer] the reverend señor [mister] Bachelor Serrano, priest of our Lady. Witnesses: Baltasar Vázquez sacristan and I baptized him and signed my name. / The Bachelor Serrano][original research?][citation needed]

Cervantes' family was from Córdoba, in Andalusia.[citation needed] His siblings were Andrés (born 1543), Andrea (born 1544), Luisa (born 1546), Rodrigo (born 1550), Magdalena (born 1554) and Juan (year of birth unknown, but mentioned in his father's will).[citation needed] Cervantes father, Rodrigo de Cervantes, was a barber-surgeon (not a physician), and so set bones, performed blood-lettings, and attended to "lesser medical needs",[15] including—as was common at the time—minor surgery.[citation needed] His paternal grandfather, Juan de Cervantes, was an influential lawyer who held several administrative positions, and his uncle was mayor of Cabra for many years.[citation needed] His mother, Leonor de Cortinas, who died on 19 October 1593, was a native of Arganda del Rey.[citation needed]

Little is known of Cervantes' early years;[according to whom?] it seems he spent much of his childhood moving from town to town with his family, whose situation was close to poverty.[citation needed] The only documentation of his education that has been identified[according to whom?] is evidence that Juan López de Hoyos, head of the "Estudio de la Villa de Madrid" [School of the Town of Madrid] called him his "beloved disciple" in an anthology in which he included Cervantes' first published works (3 poems).[citation needed] It has been speculated that he studied at the University of Salamanca,[weasel words][citation needed] but there is no evidence supporting it.[citation needed] Based on the high praise of the Jesuits in the Dialogue of the Dogs, there has been speculation that Cervantes studied with them, but again there is no evidence.[weasel words][citation needed] It is clear that Cervantes could not read Latin,[citation needed] which was an informal requirement to be considered educated in humanities at the time.[citation needed]

Military service and captivity

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2019) |

The reason that Cervantes left Spain is unknown. Possible reasons include that he was a "student" of the same name, a "sword-wielding fugitive from justice", or fleeing from a royal warrant of arrest, for having wounded a certain Antonio de Sigura in a duel.[16][full citation needed] Like many young Spanish men who wanted to further their careers, Cervantes left for Italy. In Rome, he focused his attention on Renaissance art, architecture, and poetry – knowledge of Italian literature is discernible in his work. He found "a powerful impetus to revive the contemporary world in light of its accomplishments".[17][18]: 32 As Frederick de Armas states, "Cervantes' continuing desire for Italy, as revealed in his works, is in part a desire for a return of the Renaissance."[18]: 33

By 1570, Cervantes had enlisted as a soldier in a regiment of the Spanish Navy Marines, Infantería de Marina, stationed in Naples, then a possession of the Spanish crown.[citation needed] He was there for about a year before he saw active service.[citation needed] In September 1571, Cervantes sailed on board the Marquesa, part of the galley fleet of the Holy League that, under the command of John of Austria, the illegitimate half brother of Spain's Phillip II, defeated the Ottoman fleet on 7 October 1571, in the Battle of Lepanto.[citation needed] (The Holy League was a coalition of Pope Pius V, Spain, the republics of Venice and of Genoa, the Duchy of Savoy, the Knights Hospitaller in Malta, and others.[citation needed])

According to Cervantes account,[according to whom?] though taken with fever, Cervantes refused to stay below, instead demanding to take part in the battle—saying he would rather die for his God and king than keep under cover.[citation needed] He fought and received three gunshot wounds, two in the chest and one that rendered his left arm useless.[citation needed] In Journey to Parnassus, Cervantes would say that he "...had lost the movement of the left hand for the glory of the right",[This quote needs a citation] referring to the success of his writing Don Quixote.[citation needed] Cervantes recounted his conduct in the battle with pride, believing he had taken part in an event that shaped the course of European history.[citation needed] However, a Cervantine scholar has questioned this traditional narrative of Cervantes' heroism, pointing out that the whole story comes from Cervantes himself, with no external confirmation,[19] and that Cervantes constantly praised himself.[20]: 49

After the Battle of Lepanto, Cervantes remained in hospital in Messina, Italy, for about six months, before his wounds healed enough to allow his joining the military again.[21][full citation needed] From 1572 to 1575, based mainly in Naples, he continued his soldier's life: he participated in expeditions to Corfu and Navarino, and saw the fall of Tunis and La Goulette to the Turks in 1574.[6]

On 6 or 7 September 1575, Cervantes set sail on the galley Sol from Naples to Barcelona, with letters of commendation to the king from the Duke of Sessa.[22][full citation needed] On the morning of 26 September, as the Sol approached the Catalan coast, it was attacked by Ottoman pirates and he was taken to Algiers, which had become one of the main and most cosmopolitan cities of the Ottoman Empire, and was kept there in captivity between the years of 1575 and 1580.[23][better source needed] After almost five years, and four unsuccessful escape attempts, he was ransomed by his parents and the Trinitarians and returned to his family in Madrid.[citation needed]

Later life

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: to rationalise and integrate two competing, related blocks of text—paragraphs 1 and 2, following—and in doing so, add SOURCES for the current, largely untraceable history (as a prelude to doing the same to similar large sections above). (December 2019) |

On 12 December 1584, in Esquivias, Spain, Cervantes married the much younger Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (born Esquivias, d. 31 October 1626),[14] daughter of Fernando de Salazar y Vozmediano and Catalina de Palacios.[citation needed] Over the next 20 years, Cervantes led a nomadic existence, working as a purchasing agent for the Spanish Armada and as a tax collector.[citation needed] He suffered bankruptcy and was imprisoned at least twice (1597 and 1602) for irregularities in his accounts.[14] Between 1596 and 1600, he lived primarily in Seville. In 1606, Cervantes settled in Madrid, where he remained for the rest of his life.[24]

Two further periods of his life that are very well documented are his years of work in Andalucía as a purchasing agent for the Spanish navy (i.e., the King).[when?][citation needed] This led to his imprisonment for a few months in Seville after a banker with whom he had deposited Crown funds went bankrupt.[when?][citation needed] (Cervantes says that Don Quixote was "engendered" in a prison,[This quote needs a citation] and that is presumably a reference to this episode.[editorializing][citation needed]) Cervantes also worked as a tax collector, traveling from town to town collecting back taxes due the crown.[when?][citation needed] He applied unsuccessfully for "one of four vacant positions in the New World",[This quote needs a citation] including as an accountant for the port of Cartagena and as governor of La Paz.[citation needed] At the time he was living in Valladolid, then briefly the capital (1601–1606), and finishing Don Quixote Part One, he was presumably working in the banking industry, or a related occupation where his accounting skills could be put to use.[editorialising][citation needed] He was turned down for a position as secretary to the Count of Lemos, although he did receive some type of pension from him, which permitted him to write full-time during his final years (about 1610 to 1616).[citation needed]

In July 1613 Cervantes joined the Third Order Franciscan.[25][full citation needed]

Literary pursuits

| Literature of Spain |

|---|

| • Medieval literature |

| • Renaissance |

| • Miguel de Cervantes |

| • Baroque |

| • Enlightenment |

| • Romanticism |

| • Realism |

| • Modernismo |

| • Generation of '98 |

| • Novecentismo |

| • Generation of '27 |

| • Literature subsequent to the Civil War |

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2015) |

Cervantes led a middle-class life after his return to Spain.[citation needed] Like almost all authors of his day, he was unable to support himself through his writings.[according to whom?][citation needed]

Cervantes published his first major work, La Galatea,[14] a pastoral romance, in 1585, at the same time that some of his plays, now lost – except for El trato de Argel (where he dealt with the life of Christian captives in Algiers) and El cerco de Numancia – were playing on the stages of Madrid.[citation needed] La Galatea received little contemporary notice, and Cervantes never wrote the continuation for it, which he repeatedly promised to do. Cervantes next turned his attention to drama, hoping to derive an income from that source, but his plays failed.[26] Aside from his plays, his most ambitious work in verse was Viaje del Parnaso (1614)—an allegory that consisted largely of a tedious but good-natured review of contemporary poets. Cervantes himself realized that he was deficient in poetic talent.[14]

Cervantes asserts in the prologue of Don Quixote that the work was conceived while he was in jail.[27][full citation needed] Cervantes wanted to give a picture of real life and manners and to express himself in clear language. The intrusion of everyday speech into a literary context was acclaimed by the reading public. The author stayed poor until January 1605, when the first part of Don Quixote appeared.[14]

The popularity of Don Quixote led to the publication of an unauthorized continuation of it by an unknown writer,[26] who masqueraded under the name of Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda.[14] Cervantes produced his own continuation, or Second Part, of Don Quixote,[26] which appeared in 1615.[14] He had promised the publication of a second part in 1613 in the foreword to the Novelas ejemplares (Exemplary Novels), a year before the publication of Avellaneda's book. Don Quixote has been regarded chiefly as a novel of purpose.[26] It is stated again and again that he wrote it to attack the chivalric romance, challenging the popularity of a form of literature that had been a favorite for more than a century.[28]

| "What I cannot help taking amiss is that he[c] charges me with being old and one-handed, as if it had been in my power to keep time from passing over me, or as if the loss of my hand had been brought about in some tavern, and not on the grandest occasion the past or present has seen, or the future can hope to see. If my wounds have no beauty to the beholder's eye, they are, at least, honorable in the estimation of those who know where they were received; for the soldier shows to greater advantage dead in battle than alive in flight." – from the Preface to Volume 2 of Don Quixote[29] |

Don Quixote certainly reveals much narrative power, considerable humor, a mastery of dialogue, and a forceful style. Of the two parts written by Cervantes,[26] perhaps the first is the more popular with the general public – containing the famous episodes of the tilting at windmills, the attack on the flock of sheep, the vigil in the courtyard of the inn, and the episode with the barber and the shaving basin.[14] The second part shows more constructive insight, better delineation of character, improved style, and more realism and probability in its action.[26] Most people agree that it is richer and more profound.[14]

Not surprisingly, the traumatic period of Cervantes' life in Algiers supplied subject matter for several of his literary works, notably the Captive's tale in Don Quixote and the two plays set in Algiers—El trato de Argel (Life in Algiers) and Los baños de Argel (The Dungeons of Algiers)—as well as episodes in a number of other writings, although never in straight autobiographical form.[14]

In 1613, he published a collection of tales,[26] the Exemplary Novels,[14] some of which he had written earlier. The picaroon strain, already made familiar in Spain through the picaresque novels of Lazarillo de Tormes and his successors, appears in one or another of them, especially in the Rinconete y Cortadillo.[26] In 1614, he published the Viaje del Parnaso and in 1615, the Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes. At the same time,[14] Cervantes continued working on Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, a novel of adventurous travel, completed just before his death,[26] and appearing posthumously in January 1617.[14]

Death

During the first months of 1616 his health deteriorated. On 2 April, when he was already too weak to leave his house, he was professed a Third Order Franciscan.[30][full citation needed] His last known written words–the dedication to Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda–were written, he tells us, after having received Extreme Unction.[31]

Cervantes died in Madrid on 22 April 1616[32][31] of type II diabetes,[31] and was buried the next day, 23 April.[33] The cause of his death, according to Antonio López Alonso, a modern physician who has examined the surviving documentation, was type 2 diabetes, a result of a cirrhosis of the liver. This is the best explanation for the intense thirst of which he complained just prior to his death. The cirrhosis is not believed to have been caused by alcoholism; Cervantes was too productive, especially in his final years, to have been an alcoholic.[34] For many years, some references listed 23 April 1616 as the date of his death,[weasel words][citation needed] and that is still the date when his death is widely commemorated.[citation needed][d]

In accordance with Cervantes' will, he was buried in the neighboring Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, in central Madrid.[35] His bones went missing in 1673 when building work was done at the convent, and were known to have been taken to a different convent and returned later. A project promoted and led by Fernando de Prado began in 2014 to rediscover his remains.[36]

In January 2015, it was reported that researchers searching for Cervantes' remains had found part of a casket bearing his initials, MC, at the convent. Francisco Etxeberria, the forensic anthropologist leading the search, said: "Remains of caskets were found, wood, rocks, some bone fragments, and indeed one of the fragments of a board of one of the caskets had the letters 'M.C.' formed in tacks." The first significant search for Cervantes' remains had been launched in May 2014 and had involved the use of infrared cameras, 3D scanners and ground-penetrating radar. The team had identified 33 alcoves where bones could be stored.[37][38]

On 17 March 2015, it was reported that Cervantes' remains had been discovered, along with those of his wife and others, at the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians.[39] Through documentary research, archaeologists stated that they had identified the remains as those of Cervantes. Clues from Cervantes' life, such as the loss of the use of his left hand at age 24 and the fact that he had taken at least one bullet to the chest, were hoped to help in the identification. Historian Fernando de Prado had spent more than four years trying to find funding before Madrid City Council had agreed to pay. DNA testing would now be carried out in an attempt to confirm the findings.[40]

On 11 June 2015, the remains of Cervantes were given a formal burial at a Madrid convent, containing a monument holding bone fragments that were believed to have been the authors. The city mayor Ana Botella and military attended the event.[41]

Works

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

- La Galatea (1585), the pastoral romance, which Cervantes wrote in his youth, is an imitation of the Diana of Jorge de Montemor and bears an even closer resemblance to Gil Polo's continuation of that romance. Next to Don Quixote and the Novelas ejemplares, it is particularly worthy of attention, as it manifests the poetic direction Cervantes moved in at an early period of life. La Galatea is divided in six books, inside the sixth book there is the poem known as "Canto de Calíope" (Caliope's Song) where Cervantes prises one hundred poets of his times.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605): First volume of Don Quixote.

- Novelas ejemplares (1613): a collection of 12 short stories of varied types about the social, political, and historical problems of Cervantes' Spain:

- "La gitanilla" ("The Gypsy Girl")

- "El amante liberal" ("The Generous Lover")

- "Rinconete y Cortadillo" ("Rinconete & Cortadillo")

- "La española inglesa" ("The English Spanish Lady")

- "El licenciado Vidriera" ("The Lawyer of Glass")

- "La fuerza de la sangre" ("The Power of Blood")

- "El celoso extremeño" ("The Jealous Man From Extremadura")[14]

- "La ilustre fregona" ("The Illustrious Kitchen-Maid")

- "Novela de las dos doncellas" ("The Novel of the Two Damsels")

- "Novela de la señora Cornelia" ("The Novel of Lady Cornelia")

- "Novela del casamiento engañoso" ("The Novel of the Deceitful Marriage")

- "El coloquio de los perros" ("The Dialogue of the Dogs")

- Segunda Parte del Ingenioso Cavallero [sic] Don Quixote de la Mancha (1615): Second volume of Don Quixote.

- Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda (1617). Persiles, as it is commonly known, is the best evidence not only of the survival of Byzantine novel themes but also of the survival of forms and ideas of the Spanish novel of the second Renaissance. In this work, published after the author's death, Cervantes relates the ideal love and unbelievable vicissitudes of a couple, who, starting from the Arctic regions, arrive in Rome, where they find a happy ending to their complicated adventure.

Don Quixote

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (December 2019) |

Don Quixote (spelled "Quijote" in modern Spanish) consists of two somewhat different parts, published 10 years apart. They present the life and death of an impoverished, small-town nobleman named, Cervantes tells us at the end, Alonso Quijano. His excessive readings of romances of chivalry, led him to lose his mind, and he imagines himself Don Quixote de la Mancha, a hero who carries his enthusiasm and self-deception to unintentional and comic ends. On one level, Don Quixote works as a satire of the romances of chivalry, which, though still popular in Cervantes' time, had become an object of ridicule among more demanding critics. The choice of a madman as hero also served a critical purpose, for it was "the impression of ill-being or 'in-sanity,' rather than a finding of dementia or psychosis in clinical terms, that defined the madman for Cervantes and his contemporaries." Indeed, the concept of madness was "associated with physical or moral displacement, as may be seen in the literal and figurative sense of the adjectives eccentric, extravagant, deviant, aberrant, etc."[42] The novel allows Cervantes to illuminate various aspects of human nature. Because the novel, particularly the first part, was written in individually published sections, the composition includes several incongruities. Cervantes pointed out some of these errors in the preface to the second part; but he disdained to correct them, because he conceived that they had been too severely condemned by his critics.

Cervantes felt a passion for the vivid painting of character. Don Quixote is noble-minded, an enthusiastic admirer of everything good and great, yet having all these fine qualities accidentally blended with a relative kind of madness. He is paired with a character of opposite qualities, Sancho Panza, a man of low self-esteem, who is a compound of grossness and simplicity.

Don Quixote is cited as the first classic model of the modern romance or novel,[according to whom?] and it has served as the prototype of the comic novel.[citation needed] The humorous situations are mostly burlesque, and it includes satire.

Don Quixote is one of the Encyclopædia Britannica's Great Books of the Western World, while the Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky called it "the ultimate and most sublime work of human thinking".[43] It is in Don Quixote that Cervantes coined the popular phrase "the proof of the pudding is in the eating" (por la muestra se conoce el paño), which still sees heavy use in the shortened form of "the proof is in the pudding", and "who walks much and reads much, knows much and sees much" (quien anda mucho y lee mucho, sabe mucho y ve mucho).

Exemplary novels

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (December 2019) |

Cervantes intended his novels should be to Spanish nearly what the novellas of Boccaccio were to Italians.[e] Some are anecdotes, some are romances in miniature, some are serious, some comic; they are written in a light, smooth, conversational style.

Four novelas, though favorites in Cervantes' day, are perhaps of less interest today than the rest: El amante liberal, La señora Cornelia, Las dos doncellas, and La española inglesa. The common theme to these is pairs of lovers (couples) separated by lamentable and complicated events. They are finally reunited to find the happiness they have longed for. The heroines are all beautiful and of perfect behavior. They and their lovers are capable of the highest sacrifices and try to elevate themselves to the ideal of moral and aristocratic distinction that illuminates their lives.

In El amante liberal, the beautiful Leonisa and her lover Ricardo are carried off by Turkish pirates. Both fight against serious material and moral dangers. Ricardo conquers all obstacles, returns to his homeland with Leonisa, and is ready to renounce his passion and to hand her over to her former lover in an outburst of generosity; but Leonisa's preference naturally settles on Ricardo in the end.

Another group of "exemplary" novels is formed by La fuerza de la sangre, La ilustre fregona, La gitanilla, and El celoso extremeño. The first three offer examples of love and adventure happily resolved, though only on the surface and in purely social terms, for the marriages that occur at their conclusions are morally deficient and repugnant to discerning readers.[44] The last of the four unravels itself tragically. It deals with the aged Felipe Carrizales, who, after travelling widely and becoming rich in America, decides to marry, taking all the precautions necessary to forestall being betrayed, as he had in his youth. He weds a very young girl and isolates her from the world by enclosing her in a well-guarded house with no windows. In spite of these defensive measures, a bold youth succeeds in penetrating the fortress of conjugal honour and one day Carrizales surprises his wife asleep in the arms of this would-be seducer. Carrizales mistakenly assumes that his wife has succumbed to the youth's advances, whereas in fact she did not. Nevertheless, Carrizales pardons those whom he believes are adulterers, recognizing that he is more to blame than they, and dies of sorrow over the grievous error he has committed. Cervantes here calls into question the social ideal of honour to privilege instead free will and the value of the individual.

Rinconete y Cortadillo, El casamiento engañoso, El licenciado Vidriera, and the untitled novella known today as El coloquio de los perros, four works of art that are concerned more with the personalities of the characters than with the subject matter, form the final group of stories. The protagonists are, respectively, two young vagabonds, Pedro del Rincón and Diego Cortado, Lieutenant Campuzano, a student – Tomás Rodaja (who goes mad and believes he has become glass, and who makes many remarks on society and customs of the time) and finally two dogs, Cipión and Berganza, whose wandering existence serves as a commentary on the picaresque novel.

The two young vagabonds of Rinconete y Cortadillo come by chance to Seville, and also attracted by the riches and disorder that 16th-century commerce with the Americas had brought to that metropolis. There they come into contact with a brotherhood of thieves, the Thieves' Guild, led by Monipodio, whose house is the headquarters of the Sevillian underworld. The solemn ritual of this band of ruffians is all the more comic for being presented in Cervantes' drily humorous style.

Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda

Cervantes finished the romance of The Labours of Persiles and Sigismunda shortly before his death. The idea of this romance was not new and Cervantes appears to imitate Heliodorus.[45] The work is a romantic description of travels, both by sea and land. Real and fabulous geography and history are mixed together and, in the second half of the romance, the scene is transferred to Spain and Italy. The book ends with a visit to the Pope and the Christian marriage of the two protagonists, whose identity has been concealed.

Poetry

Some of his poems are found in La Galatea. He also wrote Dos Canciones à la Armada Invencible. His best work, however, is found in the sonnets, particularly Al Túmulo del Rey Felipe en Sevilla. Among his most important poems, Canto de Calíope, Epístola a Mateo Vázquez, and the Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus – 1614) stand out. The latter is his most ambitious work in verse, an allegory that consists largely of reviews of contemporary poets. Compared to his ability as a novelist, Cervantes is generally considered a mediocre poet.

Viaje del Parnaso

The prose of the Galatea, which is in other respects so beautiful, is occasionally overloaded with epithet. Cervantes displays a totally different kind of poetic talent in the Viaje del Parnaso, an extended commentary on the Spanish authors of his time.

Plays

Comparisons to more famous playwrights, those that use more popular structures and have more authority over the world of theatre, have diminished the reputation of his plays; but two of them (Trato de Argel and La Numancia – 1582 – neither published until centuries after his death) made an impact. Trato de Argel is written in 5 acts; based on his experiences as a captive of the Moors, the play deals with the life of Christian slaves in Algiers. La Numancia is a description of the siege of Numantia by the Romans. It details the horrors of the siege, and has been described as devoid of the requisites of dramatic art (he ignores structure and changes scheme and syllables per line many times throughout). Cervantes's output published in his lifetime consists of 16 dramatic works including eight full-length plays (Spanish links to plays included):

- El gallardo español,[46]

- Los baños de Argel,[47]

- La gran sultana, Doña Catalina de Oviedo,[48]

- La casa de los celos,[49]

- El laberinto de amor,[50]

- La entretenida,[51]

- El rufián dichoso,[52]

- Pedro de Urdemalas,[53] a sensitive play about a picaro, who joins a group of Gypsies for love of a girl.

He also wrote 8 short farces (entremeses):

- El juez de los divorcios,[54]

- El rufián viudo llamado Trampagos,[55]

- La elección de los Alcaldes de Daganzo,[56]

- La guarda cuidadosa[57] (The Vigilant Sentinel),[57]

- El vizcaíno fingido,[58]

- El retablo de las maravillas,[59]

- La cueva de Salamanca,

- El viejo celoso[60] (The Jealous Old Man).

These plays and entremeses made up Ocho Comedias y ocho entire messes nuevos, nunca representados[61] (Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes, Never Before Performed), which appeared in 1615.[citation needed] The dates and order of composition of Cervantes' entremeses are unknown.[citation needed] Faithful to the spirit of Lope de Rueda, Cervantes endowed them with novelistic elements, such as simplified plot, the type of descriptions normally associated with a novel, and character development. Cervantes included some of his dramas among the works he was most satisfied with.[citation needed]

Scholars generally believe that Cervantes, above all, wanted to be a dramatist, to see his plays reach fruition.[weasel words][citation needed] He thought that if only people with standing would view his works, they would see what he had to offer.[citation needed] The evidence is so strong for this that, "In all probability he would have given all the success of 'Don Quixote,' nay, would have seen every copy of 'Don Quixote' burned in the Plaza Mayor, for one such success as Lope de Vega was enjoying on an average once a week."[62] His lack of care for Don Quixote when it was published further illustrates this desire for theatrical glory.[citation needed] The novel, initially uncelebrated by its author, was strung together and offered to its audience as a literary trifle whose object was merely to relieve boredom or act as a springboard towards other ideas, despite the profound legacy it would later develop.[62]

La Numancia

This play is a dramatization of the long and brutal siege of the Celtiberian town Numantia by the Roman forces of Scipio Africanus, completing the transformation of the Iberian peninsula to the Roman province Hispania (España). It is a story of local resistance against the foreign (Roman) invader, intended as a patriotic work.

Cervantes invented, along with the subject of his piece, a peculiar style of tragic composition; he had no knowledge of Aristotle's now-famous lectures on tragedy. He wanted to produce a piece full of tragic situations, combined with the charm of the marvellous. To accomplish this, Cervantes relied heavily on allegory and on mythological elements.

The tragedy is written in conformity with no rules, save those the author prescribed for himself, for he felt no inclination to imitate the Greek forms. He divides the play into four acts (jornadas) with no chorus. The dialogue is sometimes in tercets, and sometimes in redondillas, and for the most part in octaves – without any regard to rule.

Legacy

During his life, Cervantes was primarily known as a writer of comedy, which was how his contemporaries viewed Don Quixote Part I.[citation needed] His Novelas ejemplares were better received[citation needed] than Don Quixote and allowed him to publish his plays and entremeses, Viaje del Parnaso, Part II of Don Quixote, and (by his widow) Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda. He then faded into semi-obscurity.[citation needed] Interest in him first revived in England in the 18th century, first by the deluxe edition of Tonson, for which the first biographical sketch was written (1738), and then by the scholarly editor John Bowle, who was the first to call Cervantes a "classic" author.[citation needed] This began his influence on other novelists and then an intense interest by the German romantics in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[citation needed] The tricentennial, 1905, saw a great wave of celebrations in Spain.[citation needed] The year 2016, the 400th anniversary of Cervantes' death, saw the production of Cervantina, a celebration of the author's plays by the Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico in Madrid.

Cervantes' novel Don Quixote has had a tremendous influence on the development of prose fiction. It has been translated into all major languages and has appeared in 700 editions. The first translation was in English, made by Thomas Shelton in 1608 (Part I only[63]), but not published until 1612. Shelton renders some Spanish idioms into English so literally that they sound nonsensical when translated.[citation needed] As an example Shelton always translates the word dedos as fingers, not realizing that dedos can also mean inches. (In the original Spanish, for instance, a phrase such as una altura de quince dedos, which makes perfect sense in Spanish, would mean "fifteen inches high" in English, but a translator who renders it too literally would translate it as "fifteen fingers high".

Carlos Fuentes raised the possibility that Cervantes and William Shakespeare were the same person, in the sense that Homer, Dante, Defoe, Dickens, Balzac, and Joyce are all the same writer whose spirit wanders through the centuries.[64] Fuentes noted that "Cervantes leaves the page open where the reader knows himself read and the author written."[65][66]

Sigmund Freud was greatly influenced by El coloquio de los perros, which has been called the origin of psychoanalysis. In it, only one character tells his story; the other listens, occasionally making comments. At the center of the dog's story is a sexual event. Freud stated that he learned Spanish so as to read Cervantes in the original, and he signed 55 letters with the name of the character (dog) Cipión.[67][68][69]

The Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, the largest digital archive of Spanish-language historical and literary works in the world, is named after the author.[citation needed]

References in other works

Don Quixote has been the subject of a variety of works in other fields of art, including:

Ballets

- A 1965 production of Nicolas Nabokov's Don Quixote with choreography by George Balanchine.[70]

- A 2011 production of The Inquisition of Don Miguel with choreography by Sallyann Mulcahy (Ballet Montana) to Richard Strauss’ Opus 35, Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character

Films

- Don Quixote (1933) directed by G. W. Pabst

- A Soviet film, Дон Кихот (Don Quixote) (1957) directed by Grigori Kozintsev

- Man of La Mancha (1972), directed by Arthur Hiller, a film adaptation of the 1965 musical

- The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018), directed by Terry Gilliam

Literature

Don Quixote's influence can be seen in the work of:

- Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Tobias Smollett, and Laurence Sterne

- The classic 19th-century novelists Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Gustave Flaubert, Herman Melville, Sir Walter Scott, and Mark Twain

- The 20th-century works of Jorge Luis Borges, Giannina Braschi, and James Joyce.

Opera

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Don Quichotte auf der Hochzeit des Comacho (1761)

- Giovanni Paisiello: Don Chisciotte della Mancia (1769)

- Antonio Salieri: Don Chisciotte alle nozze di Gamace (1770/1771)

- Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Don Quixote der Zweyte (1795)

- Felix Mendelssohn: Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1825)

- Saverio Mercadante: Don Chisciotte alle nozze di Gamaccio (1830)

- Wilhelm Kienzl: Don Quixote, op. 50 (1897)

- Jules Massenet: Don Quichotte (1910)

- Manuel de Falla: El retablo de maese Pedro (1923)

- Cristóbal Halffter: Don Quijote (1996–99)

Operetta

- Richard Heuberger: Don Quixote (1910)

Ballet

- Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Don Quichotte chez la Duchesse (1743)

- Ludwig Minkus: Don Quixote (1869)

- Jacques Ibert: Le Chevalier Errant (1950)

- Roberto Gerhard: Don Quixote (1950)

- Nicolas Nabokov: Don Quixote (1966)

Incidental music

- Henry Purcell: Comical History of Don Quixote (1694/95)

Orchestral

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Burlesque de Don Quixote, Overture-suite in G for strings and basso continuo

- Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, cello and orchestra, Op. 35 (1897)

Musicals

- Man of La Mancha (1965), an American musical by Dale Wasserman, Mitch Leigh, and Joe Darion

Songs

- Maurice Ravel: Don Quichotte à Dulcinée (1932)

- A song, "Dom Quixote," by Brazilian tropicalia-pioneers Os Mutantes, from the album Mutantes (1969)

- Nik Kershaw: Don Quixote (1985)

- Gordon Lightfoot: Don Quixote (song and album)(1972)

Piano

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Don Quixote. Six Character pieces (1908)

Visual art

- Pablo Picasso painted a picture illustrating a scene from Don Quixote.

- In 1965, Salvador Dali created a Cervantes etching as part of the "Five Spanish Immortals' series (also included El Cid, El Greco, Velazquez, and Don Quixote).

- The theme of the novel also inspired the 19th-century French artists Honoré Daumier and Gustave Doré.[citation needed]

Places

- Cervantes. A municipality in the province of Lugo, Galicia, Spain, but the name of the town is not based on Miguel de Cervantes (nor is there any evidence tying him or his family to this town).

- Cervantes. A municipality in the province of Ilocos Sur, Philippines.

- Cervantes. A township situated north of the Western Australian state capital Perth in Australia.

Television

- The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Episode 2 "Huck of La Mancha" features the live-action Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, and Becky Thatcher helping the animated Don Quixote and Sancho to challenge the brigand leader Don Jose (1968).

- Play of the Month. Season 8, Episode 5 "The Adventures of Don Quixote," with Rex Harrison in the title role (1973).

- Cervantes is a recurring character in the Spanish television show El ministerio del tiempo, portrayed by actor Pere Ponce.

Controversy about ethnic and religious background

The great watershed in modern Spanish intellectual history was the discovery in the 20th century, first by Spanish exile and Princeton professor Américo Castro, that many notable people including some Christian saints, were the descendents of Spanish Jews (Sephardim). It has been estimated that 80% of the writers of Cervantes' day had Jewish ancestry.[71]

Modern scholars, especially in the United States, where Castro taught and had disciples, have suggested that his ancestors, before 1492, were Jews, and that he was therefore a New Christian or (the same thing) Converso, a group subject to much discrimination in the Spain of his day. This was the topic of a plenary address by Daniel Eisenberg to the Asociación de Cervantistas, in which he also suggests Don Quijote was thought of by Cervantes as a New Christian and Sancho an Old Christian.[72] Others who have written endorsing this view are Rosa Rossi[73] and Howard Mancing.[74] Eisenberg suggests that Cervantes' mother was a New Christian as well. However, the theory rests almost exclusively on circumstantial evidence, but would explain some mysteries of Cervantes' life.[75] Others such as Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz or Francisco Olmos Garcia (who considers it a "tired issue" and only supported by Américo Castro) strongly reject the theory.[76]

Likeness

Although the portrait of Cervantes attributed to Juan de Jáuregui is the one most associated with the author, there is no known portrait that is really a true likeness.[77][78]

The oil painting Retrato de un caballero desconocido (Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman), painted by El Greco in Toledo between 1600 and 1605, and on display at the Museo del Prado, has also been cited as a possible portrait of Cervantes, based on the fact that he was living near Toledo in 1604 and that he knew people within El Greco's circle of friends.[79]

The 1859 portrait by Luis de Madrazo, which the painter himself stated is based on his own imagination, is currently at the Biblioteca Nacional de España.[80]

The Spanish euro coins of €0.10, €0.20, and €0.50 bear an image of a bust of Cervantes.[81]

See also

Notes

- ^ The portrait is a well-known one, supposedly from the hand of Juan de Jáuregui. However, no authenticated image of Cervantes exists; the original Jáuregui painting is lost, and so was itself never authenticated (and the names of Cervantes and Jáuregui on it were added centuries after it was painted). Arguably the most reliable description of the writer is was provided by Cervantes himself in the author's preface of the Exemplary Novels, where he complained that the lost portrait by Juan Martínez de Jáuregui y Aguilar was not used as a frontispiece.[1][verification needed]

This person whom you see here, with an oval visage, chestnut hair, smooth open forehead, lively eyes, a hooked but well-proportioned nose, and silvery beard that twenty years ago was golden, large moustaches, a small mouth, teeth not much to speak of, for he has but six, in bad condition and worse placed, no two of them corresponding to each other, a figure midway between the two extremes, neither tall nor short, a vivid complexion, rather fair than dark, somewhat stooped in the shoulders, and not very lightfooted: this, I say, is the author of Galatea, Don Quixote de la Mancha, The Journey to Parnassus, which he wrote in imitation of Cesare Caporali Perusino, and other works which are current among the public, and perhaps without the author's name. He is commonly called MIGUEL DE CERVANTES SAAVEDRA. [Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra][1][verification needed]

- ^ His signature spells Cerbantes with a b; but he is now known after the spelling Cervantes, used by the printers of his works. The patronymic of his mother was Cortinas. Saavedra was the surname of a distant relative. He adopted it as his second surname after his return from the Barbary Coast.[5][6] The earliest documents signed with Cervantes' two names, Cervantes Saavedra, appear several years after his repatriation. He began adding the second surname Saavedra to his patronymic in 1586–1587 in official documents related to his marriage to Catalina de Salazar.[6]

- ^ "He" refers to the writer of a spurious Part II of Don Quixote (Second Volume of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha) known under the pseudonym Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. Avellaneda had referred to Cervantes as an "old and one-handed" man.

- ^ Cervantes is commemorated on this date, along with William Shakespeare,[citation needed] though the date for Cervantes was according to the Gregorian Calendar while the date for Shakespeare was according to the Julian Calendar, and therefore 10 days later in real time.[citation needed]

- ^ The Spanish title of novelas is misleading. In modern Spanish it means novels, but Cervantes used it to mean the shorter Italian novella. See the Novel article for the terminological problem.

References

- ^ a b Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de (22 December 2004). Novelas ejemplares [1613] [Exemplary Novels] (E-book). Translated by Kelly, Walter K. Project Gutenberg. p. Unknown. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Chacón y Calvo, José María (1947–48). "Retratos de Cervantes". Anales de la Academia Nacional de Artes y Letras (in Spanish). 27: 5–17.

- ^ Ferrari, Enrique Lafuente (1948). La novela ejemplar de los retratos de Cervantes (in Spanish). Madrid, ES: Unknown publisher. p. Unknown.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Armstrong, Richard. "Time Out of Joint". Engines of Our Ingenuity. Lienhard, John (host, producer). Retrieved 9 December 2019 – via UH.edu.

- ^ a b Slade, Carol (2004). "Introduction". Don Quixote. p. xxiv.

- ^ a b c d Garcés, Maria Antonia (2002). Cervantes in Algiers: A Captive's Tale. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 191–192, 220.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Cervantes, Miguel de". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Amadeu Àrias, Juli (22 April 2016). "El 'Quijote', tantas traducciones como locuras soñó su hidalgo". 20 Minutos (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Harold Bloom on Don Quixote, the first modern novel". The Guardian. London. 12 December 2003. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Don Quixote gets authors' votes". BBC News. 7 May 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "La lengua de Cervantes" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de la Presidencia de España. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "La Epístola a Mateo Vázquez: historia de una polémica literaria en torno a Cervantes". Centro de Estudios Cervantinos. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Lucía Megías, José Manuel (2016). La Juventud de Cervantes: Una Vida en Construcción [The Youth of Cervantes: A Life Under Construction]. Cróncas de la Historia (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid, ES: EDAF. p. Unknown. ISBN 9788441436312. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

Años de disputas, años de engaños, años de dudas que zanjaron los biógrafos del siglos XVIII (Vincente de los Ríos y Juan Antonio Pellicer) y del siglo XIX (con Fernández de Navarrete a la cabeza): Miguel de Cervantes es natural de la villa de Alcalá de Henares, donde fue bautizado un 9 de octubre de 1547 (según el calendario vigente, el juliano). / [block-quoting] Domingo, nueve días del mes de otubre año de Señor de mil e quinientos e cuarenta e siete años, fue baptizado Miguel, hijo de Rodrigo de Cervantes e su mujer doña Leonor; fueron sus compadres Juan Pardo. Baptizole el reverendo señor bachiller Serrano, cura de nuestra Señora. Testigos: Baltasar Vázquez sacristán e yo que lo baptizé y firmé de mi nombre. / El bachiller Serrano

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Miguel de Cervantes at the Encyclopædia Britannica[full citation needed]

- ^ Byron, William (1978). Cervantes: A Biography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 23–32.[page range too broad]

- ^ The Enigma of Cervantine Genealogy, 118.[full citation needed]

- ^ This quote is de Armas, apparently quoting Charles L. Stinger. See de Armas (2002), op. cit., pp. 32 and 54.

- ^ a b de Armas, Frederick A. (2002). "Cervantes and the Italian Renaissance". In Cascardi, Anthony J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cabbridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–57, esp. 32, 33. ISBN 9780521663878. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel (2004). "La supuesta homosexualidad de Cervantes". Siglos dorados : homenaje a Augustin Redondo. Vol. 1. Madrid: Castalia. pp. 399–410. ISBN 84-9740-100-X.

[H]ay que reconocer también que ciertas circunstancias de la vida de Cervantes son sospechosísimas.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly, The Life of Cervantes, 33.[full citation needed]

- ^ J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly, The Life of Cervantes, 41.[full citation needed]

- ^ Diego, Héctor Vielva. "Was Cervantes Ever in Istanbul?". We Love Istanbul. We Love Istanbul.

- ^ Close, A.J. (2008). A Companion to Don Quixote, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 978-1-85566-170-7, p. 12

- ^ Fitzmaurice-Kelly, James: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra; Oxford, Clarendon press 1913, p. 179 online at archive.org.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Cervantes, Miguel de (1605). El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha, Prólogo.[full citation needed]

- ^ Close, A.J. (2008). A Companion to Don Quixote, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 978-1-85566-170-7, p. 39

- ^ Miguel, de Cervantes (2015). The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. Aegitas. ISBN 978-5-00064-159-0.

- ^ Fitzmaurice-Kelly,[clarification needed] p. 201f.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c López Alonso, Antonio (1999). Enfermedad y muerte de Cervantes. Universidad de Alcalá de Henares. p. 112.

- ^ Parker, Barbara Keevil; Parker, Duane F. (2009). Miguel de Cervantes – Barbara Keevil Parker, Duane F. Parker. ISBN 978-1438106854. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ C. Calvo, Shakespeare and Cervantes in 1916, 78.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel (Fall 2014). "Un médico examina a Cervantes" (PDF). Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Miguel de Cervantes Biography – life, family, children, name, story, death, history, wife, son, book". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Giles Tremlett in Madrid. "Madrid begins search for bones of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Casket find could lead to remains of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes | Books". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Frayer, Lauren (24 June 2015). "The Reason Cervantes Asked To Be Buried Under A Convent". NPR.

- ^ "Spain finds Don Quixote writer Cervantes' tomb in Madrid". BBC. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Remains of Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, 'identified in convent'". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Giles, Ciaran (11 June 2015). "Spain formally buries Cervantes, 400 years later". Associated Press. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ David A. Boruchoff, "On the Place of Madness, Deviance, and Eccentricity in Don Quijote," Hispanic Review 70.1 (2002): 1–23; quotations on 2–3.

- ^ Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. A Writer's Diary (1873–1876). Unknown publisher. pp. Unknown pages.

- ^ Boruchoff, David A. (2009). "Free Will, the Picaresque, and the Exemplarity of Cervantes's Novelas ejemplares". Modern Language Notes. 124 (2): 372–403.

- ^ Sacchetti, Maria Alberta (2001). Cervantes' Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda: A Study of Genre. Vol. 56. Tamesis Books. pp. 489–491. doi:10.2307/1261878. ISBN 978-1-85566-077-9. JSTOR 1261878. OCLC 52263865.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Los Baños de Argel" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com.

- ^ "La Gran Sultana" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "La casa" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "El Laberinto" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "La Entretenida" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses / El rufian dichoso". cervantes.tamu.edu.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Pedro Urdamles" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "ENTREMES: EL JUEZ DE LOS DIVORCIOS". cervantes.uah.es.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "EL RUFIÁN VIUDO LLAMADO TRAMPAGOS". www.comedias.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Daganzo" (PDF). miguelde.cervantes.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Info" (PDF). www.biblioteca.org.ar. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "ENTREMES: DEL VIZCAÍNO FINGIDO". cervantes.uah.es.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "ENTREMES: DEL RETABLO DE LAS MARAVILLAS". cervantes.uah.es.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "ENTREMES: DEL VIEJO CELOSO". cervantes.uah.es.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses". cervantes.tamu.edu.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Proyecto Cervantes". cervantes.tamu.edu. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The second edition of Thomas Shelton's Don Quixote, Part I: A reassessment of the dating problem, by A.G. Lo Ré". Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Fuentes, 69–70.

- ^ Fuentes, C. (1988), Myself with Others: Selected Essays, Farrar Straus Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-52237-7

- ^ Zimmerman, Susan; Sullivan, Garrett (2008). Shakespeare Studies. ISBN 978-0838641798. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Síntoma, chiste y cinismo en el Coloquio de los perros http://cvc.cervantes.es/literatura/cervantistas/congresos/cg_2006/cg_2006_90.pdf

- ^ "Cervantes y el psicoanálisis". Razón y Palabra.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ E.C. Riley, ""Cipión" Writes to "Berganza" in the Freudian Academia Española" https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.h-net.org/~cervant/csa/artics94/riley.htm

- ^ The New Grove dictionary of American music. Hitchcock, H. Wiley (Hugh Wiley), Sadie, Stanley. New York: Grove's Dictionaries of Music. 1986. ISBN 0-943818-36-2. OCLC 13184437.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kossoff, A. David (1979). "Fuentes de "El perro del hortelano" y una teoría de la España del Siglo de Oro". Estudios sobre literatura y arte dedicados al profesor Emilio Orozco Díaz. Granada. Vol. 2. Universidad de Granada, Spain. pp. 209–213.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel (2008). La actitud de Cervantes hacia sus antepasados judaicos. Cervantes y las religiones. Actas Del Coloquio Internacional de la Asociación de Cervantistas. pp. 55–78. ISBN 978-84-8489-314-1.

- ^ Tras las huellas de Cervantes. Perfil inédito del autor del Quijote. Trans. Juan Ramón Capella. Madrid: Trotta, 2002

- ^ The Cervantes Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2004 (2 vols).

- ^ Byron, William (1978). Cervantes: A Biography. Doubleday. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-385-00279-0.

- ^ Cervantes and His Postmodern Constituencies by Anne J. Cruz, Carroll B. Johnson, p. 116

- ^ Byron, William (1978). Cervantes. A Biography. London: Cassell. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-55778-006-5.

- ^ Rojas Martínez, Ángel (ed.). Cervantes. Una identidad sin rostro (PDF) (in Spanish). University of Castilla–La Mancha. pp. 169–178. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Portrait of a Gentleman". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de España. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Programa Europa – Cervantes". Fábrica Nacional de Moneda y Timbre (in Spanish). Real Casa de la Moneda. 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Euro notes and coins: national sides". European Commission. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Fitzmaurice-Kelly, J. The Life of Cervantes.[full citation needed]

Further reading

- Cervantes: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Lowry Nelson, 1969.

- Cinco personajes fugaces en el camino de Don Quijote, Giannina Braschi; Cuadernos hispanoamericanos, ISSN 0011-250X, Nº 328, 1977, pp. 101–115.

- Critical Essays on Cervantes / ed. Ruth S. El Saffar, 1986.

- Scenes from World Literature and Portraits of Greatest Authors, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and Willi Glasauer, Círculo de Lectores, 1988.

- Cervantes's Don Quixote (Modern Critical Interpretations), ed. Harold Bloom, 2001.

- The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes, ed. Anthony J. Cascardi, 2002.

- Miguel de Cervantes (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, 2005.

- Cervantes' Don Quixote: A Casebook, ed. Roberto González Echevarría, 2005.

- Le Barbaresque, Olivier Weber, Flammarion, 2011.

- Pérez, Rolando. "What is Don Quijote/Don Quixote And…And…And the Disjunctive Synthesis of Cervantes and Kathy Acker." Cervantes ilimitado: cuatrocientos años del Quijote. Ed. Nuria Morgado. ALDEEU, 2016. 75–100.

External links

- Works by Miguel de Cervantes at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Miguel de Cervantes at Internet Archive

- Works by Miguel de Cervantes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes Spanish web site with multiple Cervantes links and audio of whole of Don Quixote

- Famous Hispanics

- The Cervantes Project with biographies and chronology

- Information about Miguel de Cervantes

- Cervantine Collection of the Biblioteca de Catalunya

- Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616): Life and Portrait The Cervantes Project. Canavaggio, Jean.

- Cervantes' Birthplace Museum

- Miguel de Cervantes Collection From the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the Library of Congress

- Cervantes' short biography in Spanish

- Cervantes' chatbot in Spanish

- Wikipedia articles needing more precise page number citations from December 2019

- Miguel de Cervantes

- Spanish novelists

- Spanish Golden Age

- 1547 births

- 1616 deaths

- Burials in Madrid

- Baroque writers

- Barbary pirates

- People from Alcalá de Henares

- Roman Catholic writers

- Spanish male dramatists and playwrights

- Spanish male novelists

- Spanish male poets

- Spanish people with disabilities

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- Spanish soldiers

- Tax collectors

- Ransom

- Accountants

- History of Algiers

- Deaths from diabetes

- 16th-century dramatists and playwrights

- 16th-century Spanish poets

- 16th-century Spanish writers

- 16th-century male writers

- 17th-century Spanish dramatists and playwrights

- 17th-century Spanish novelists

- 17th-century Spanish poets

- 17th-century Spanish writers