Molecular genetics

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the structure and/or function of genes in an organism's genome using genetic screens.[1][2] The field of study is based on the merging of several sub-fields in biology: classical Mendelian inheritance, cellular biology, molecular biology, biochemistry, and biotechnology. Researchers search for mutations in a gene or induce mutations in a gene to link a gene sequence to a specific phenotype. Molecular genetics is a powerful methodology for linking mutations to genetic conditions that may aid the search for treatments/cures for various genetics diseases.

History

For molecular genetics to develop as a discipline, several scientific discoveries were necessary. The discovery of DNA as a means to transfer the genetic code of life from one cell to another and between generations was essential for identifying the molecule responsible for heredity. Molecular genetics arose initially from studies involving genetic transformation in bacteria. In 1944 Avery, McLeod and McCarthy[3] isolated DNA from a virulent strain of S. pneumoniae, and using just this DNA were able to convert a harmless strain to virulence. They called the uptake, incorporation and expression of DNA by bacteria “transformation”. This finding suggested that DNA is the genetic material of bacteria. Since its discovery in 1944 genetic transformation has been found to occur in numerous bacterial species including many species that are pathogenic to humans.[4] Bacterial transformation is often induced by conditions of stress, and the function of transformation appears to be repair of genomic damage.[4]

The phage group was an informal network of biologists centered on Max Delbrück that contributed substantially to molecular genetics and the origins of molecular biology during the period from about 1945 to 1970.[5] The phage group took its name from bacteriophages, the bacteria-infecting viruses that the group used as experimental model organisms. Studies by molecular geneticists affiliated with this group contributed to current understanding of how gene-encoded proteins function in DNA replication, DNA repair and DNA recombination, and on how viruses are assembled from protein and nucleic acid components (molecular morphogenesis). Furthermore, the role of chain terminating codons was elucidated. One noteworthy study was performed by Sydney Brenner and collaborators using amber mutants defective in the gene encoding the major head protein of bacteriophage T4.[6] This study demonstrated the co-linearity of the gene with its encoded polypeptide, thus providing strong evidence for the "sequence hypothesis" that the amino acid sequence of a protein is specified by the nucleotide sequence of the gene determining the protein.

Watson and Crick (in conjunction with Franklin and Wilkins) figured out the structure of DNA, a cornerstone for molecular genetics.[7] The isolation of a restriction endonuclease in E. coli by Arber and Linn in 1969 opened the field of genetic engineering.[8] Restriction enzymes were used to linearize DNA for separation by electrophoresis and Southern blotting allowed for the identification of specific DNA segments via hybridization probes.[9][10] In 1971, Berg utilized restriction enzymes to create the first recombinant DNA molecule and first recombinant DNA plasmid.[11] In 1972, Cohen and Boyer created the first recombinant DNA organism by inserting recombinant DNA plasmids into E. coli, now known as bacterial transformation, and paved the way for molecular cloning.[12] The development of DNA sequencing techniques in the late 1970s, first by Maxam and Gilbert, and then by Frederick Sanger, was pivotal to molecular genetic research and enabled scientists to begin conducting genetic screens to relate genotypic sequences to phenotypes.[13] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Taq polymerase, invented by Mullis in 1985, enabled scientists to create millions of copies of a specific DNA sequence that could be used for transformation or manipulated using agarose gel separation.[14] A decade later, the first whole genome was sequenced (Haemophilus influenzae), followed by the eventual sequencing of the human genome via the Human Genome Project in 2001.[15] The culmination of all of those discoveries was a new field called genomics that links the molecular structure of a gene to the protein or RNA encoded by that segment of DNA and the functional expression of that protein within an organism.[16] Today, through the application of molecular genetic techniques, genomics is being studied in many model organisms and data is being collected in computer databases like NCBI and Ensembl. The computer analysis and comparison of genes within and between different species is called bioinformatics, and links genetic mutations on an evolutionary scale.[17]

The Central Dogma

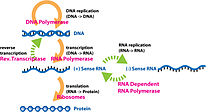

This image shows an example of the central dogma using a DNA strand being transcribed then translated and showing important enzymes used in the processes

The Central Dogma is the basis of all genetics and plays a key role in the study of molecular genetics. The Central Dogma states that DNA replicates itself, DNA is transcribed into RNA, and RNA is translated into proteins.[18] Along with the Central Dogma, the genetic code is used in understanding how RNA is translated into proteins. Replication of DNA and transcription from DNA to mRNA occurs in the nucleus while translation from RNA to proteins occurs in the ribosome.[19] The genetic code is made of four base pairs: adenine, cytosine, uracil, and guanine and is redundant meaning multiple combinations of these base pairs (which are read in triplicate) produce the same amino acid.[20] Proteomics and genomics are fields in biology that come out of the study of molecular genetics and the Central Dogma.[21]

Techniques

Forward genetics

Forward genetics is a molecular genetics technique used to identify genes or genetic mutations that produce a certain phenotype. In a genetic screen, random mutations are generated with mutagens (chemicals or radiation) or transposons and individuals are screened for the specific phenotype. Often, a secondary assay in the form of a selection may follow mutagenesis where the desired phenotype is difficult to observe, for example in bacteria or cell cultures. The cells may be transformed using a gene for antibiotic resistance or a fluorescent reporter so that the mutants with the desired phenotype are selected from the non-mutants.[22]

Mutants exhibiting the phenotype of interest are isolated and a complementation test may be performed to determine if the phenotype results from more than one gene. The mutant genes are then characterized as dominant (resulting in a gain of function), recessive (showing a loss of function), or epistatic (the mutant gene masks the phenotype of another gene). Finally, the location and specific nature of the mutation is mapped via sequencing.[23] Forward genetics is an unbiased approach and often leads to many unanticipated discoveries, but may be costly and time consuming. Model organisms like the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and the zebrafish Danio rerio have been used successfully to study phenotypes resulting from gene mutations.[24]

Reverse genetics

Reverse genetics is the term for molecular genetics techniques used to determine the phenotype resulting from an intentional mutation in a gene of interest. The phenotype is used to deduce the function of the un-mutated version of the gene. Mutations may be random or intentional changes to the gene of interest. Mutations may be a mis-sense mutation caused by nucleotide substitution, a nucleotide addition or deletion to induce a frameshift mutation, or a complete addition/deletion of a gene or gene segment. The deletion of a particular gene creates a gene knockout where the gene is not expressed and a loss of function results (e.g. knockout mice). Mis-sense mutations may cause total loss of function or result in partial loss of function, known as a knockdown. Knockdown may also be achieved by RNA interference (RNAi).[26] Alternatively, genes may be substituted into an organism's genome (also known as a transgene) to create a gene knock-in and result in a gain of function by the host.[27] Although these techniques have some inherent bias regarding the decision to link a phenotype to a particular function, it is much faster in terms of production than forward genetics because the gene of interest is already known.

See also

- Complementation (genetics)

- DNA damage (naturally occurring)

- DNA damage theory of aging

- Epigenetics

- Gene mapping

- Genetic code

- Genetic recombination

- Genomic imprinting

- History of genetics

- Homologous recombination

- Mutagenesis

- Regulation of gene expression

- Timeline of the history of genetics

- Transformation (genetics)

Sources and notes

- ^ Waters, Ken (2013), "Molecular Genetics", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2019-10-07

- ^ Alberts, Bruce (2014-11-18). Molecular biology of the cell (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780815344322. OCLC 887605755.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Avery OT, Macleod CM, McCarty M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated form pneumococcus type III. J Exp Med. 1944 Feb 1;79(2):137-58. doi: 10.1084/jem.79.2.137. PMID: 19871359; PMCID: PMC2135445

- ^ a b Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Michod RE (2018). Sex in microbial pathogens. Infection, Genetics and Evolution volume 57, pages 8-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.024

- ^ Phage and the Origins of Molecular Biology (2007) Edited by John Cairns, Gunther S. Stent, and James D. Watson, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory of Quantitative Biology, Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, New York ISBN 978-0879698003

- ^ Sarabhai AS, Stretton AO, Brenner S, Bolle A (January 1964). "Co-linearity of the gene with the polypeptide chain". Nature. 201 (4914): 13–7. Bibcode:1964Natur.201...13S. doi:10.1038/201013a0. PMID 14085558. S2CID 10179456

- ^ Tobin, Martin J. (2003-04-15). "April 25, 1953". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 167 (8): 1047–1049. doi:10.1164/rccm.2302011. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 12684243.

- ^ "Restriction Enzymes Spotlight | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ Righetti, Pier Giorgio (June 24, 2005). "Electrophoresis: The march of pennies, the march of dimes". Journal of Chromatography A. 1079 (1–2): 24–40. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2005.01.018. PMID 16038288.

- ^ "Southern Blotting | MyBioSource Learning Center". Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "Professor Paul Berg | Biographical summary". WhatisBiotechnology.org. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "Herbert W. Boyer and Stanley N. Cohen". Science History Institute. 2016-06-01. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "DNA sequencing | genetics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "The Invention of PCR". Bitesize Bio. 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "Timeline: Organisms that have had their genomes sequenced". yourgenome. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "What is genomics?". EMBL-EBI Train online. 2011-09-09. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "What is bioinformatics? A proposed definition and overview of the field". Methods of Information in Medicine. 40 (2). 2001. doi:10.1055/s-008-38405. ISSN 0026-1270.

- ^ "The Central Dogma | Protocol". www.jove.com. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "Transcription, Translation and Replication". www.atdbio.com. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "Genetic Code". Genome.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "A Brief Guide to Genomics". Genome.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ "Selection versus Screening in Directed Evolution", Directed Evolution of Selective Enzymes, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016, pp. 27–57, doi:10.1002/9783527655465.ch2, ISBN 978-3-527-65546-5

- ^ Schneeberger, Korbinian (August 20, 2014). "Using next-generation sequencing to isolate mutant genes from forward genetic screens". Nature Reviews Genetics. 15 (10): 662–676. doi:10.1038/nrg3745. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0024-CF80-4. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 25139187. S2CID 1822657.

- ^ Lawson, Nathan D.; Wolfe, Scot A. (2011-07-19). "Forward and Reverse Genetic Approaches for the Analysis of Vertebrate Development in the Zebrafish". Developmental Cell. 21 (1): 48–64. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.007. ISSN 1534-5807. PMID 21763608.

- ^ Kutscher, Lena M. (2014). "Forward and reverse mutagenesis in C. elegans". WormBook: 1–26. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.167.1. PMC 4078664. PMID 24449699.

- ^ Hardy, Serge; Legagneux, Vincent; Audic, Yann; Paillard, Luc (October 2010). "Reverse genetics in eukaryotes". Biology of the Cell. 102 (10): 561–580. doi:10.1042/BC20100038. PMC 3017359. PMID 20812916.

- ^ Doyle, Alfred; McGarry, Michael P.; Lee, Nancy A.; Lee, James J. (April 2012). "The construction of transgenic and gene knockout/knockin mouse models of human disease". Transgenic Research. 21 (2): 327–349. doi:10.1007/s11248-011-9537-3. ISSN 0962-8819. PMC 3516403. PMID 21800101.

Further reading

- Sites and databases related to genetics, cytogenetics and oncology, at Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology

- Jeremy W. Dale and Simon F. Park. 2010. Molecular Genetics of Bacteria, 5th Edition ISBN 978-0470741849

External links

Media related to Molecular genetics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Molecular genetics at Wikimedia Commons- NCBI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/About/primer/genetics_molecular.html