Multihull

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

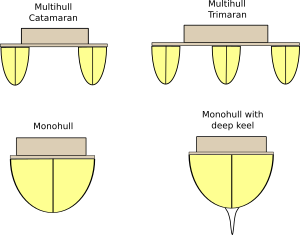

A multihull is a ship, vessel, craft or boat with more than one hull. Multihull ships (vessels, craft, boats) include multiple types, sizes and applications. Hulls range from two to five, of uniform or diverse types and arrangements

Catamarans are the most common type, with two symmetric hulls. They are used as racing, sailing, tourist and fishing boats. About 70% of fast passenger and car-passenger ferries are catamarans. About 300 semi-submersible drilling and auxiliary platforms operate at sea.

Some ships with outriggers are built, including the experimental ship Tritone (UK) and the first and second sister-ships of the series of Littoral Combat Ships (US). About 70 small waterplan area ships whose hulls have a smaller cross section at the waterplane than below the surface exist.

Multihull ships can be classified by the number of hulls, by their arrangement and by their shapes and sizes.[1]

The first multihull vessels were Austronesian canoes. They hollowed out logs to make canoes and stabilized them by attaching outriggers to prevent them from capsizing. This led to the proa, catamaran, and trimaran plus various outriggers throughout the Pacific.

Types

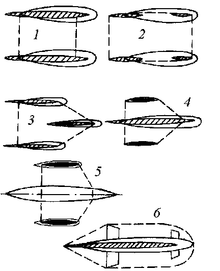

1) catamaran: two identical hulls

2) catamaran with non-symmetric hulls

3) trimaran: three symmetric hulls

4) trimaran with flat outer boards of side hulls

5) catamaran with shifted hulls

6) proa or conventional outrigger

7) triple-hull ship with smaller side hulls

Terminology

Individual hulls are connected by an above-water structure called the platform or above-water bridge. The structure can be watertight partially or fully, or can consist of separate connections.[2]

The distance between hulls is called the transverse clearance and can be measured between center planes or between the inner boards.

The distance between the design waterplane and the bottom of the above-water platform (wet deck) is called the vertical clearance.

The longitudinal distance between a triple-hull ship is called the longitudinal clearance and can be measured between the middle of the hulls or between their fore perpendiculars.

Outrigger canoe

An outrigger is a small side hull attached to the main load-carrying hull by two or more struts.

Proas have one hull and one outrigger. Engines are commonly placed on the main hull.

A ship with one hull of conventional shape and two small side hulls (outriggers) is called an outrigger ship. This type is identified as trimaran in English language publications.

Three terms from the Malay and Micronesian language group describe hull components. The terms originated as descriptions of the proa.[3] Catamarans and trimarans share the same terminology.[4]

- Ama[3] − The ama is the outrigger hull.

- Aka[3] − The aka connects the vaka to the ama. In Hawaiian, this is called the iako.

- Vaka[3] − The vaka is the main canoe-like hull.

Semantically, the catamaran is a pair of Vaka held together by Aka, whereas the trimaran is a central Vaka, with Ama on each side, attached by Aka.

Two-hull

Sometimes, the term catamaran is applied to any ship or boat consisting of two hulls. However, other twin-hull types include duplus and trisec

The history of commercial catamarans began in 17th century England. Separate attempts at steam-powered catamarans were carried out by the middle of the 20th century. However, success required better materials and more developed hydrodynamic technologies. During the second half of the 20th century catamaran designs flourished.

Three-hull

The term trimaran is often used for any triple-hull ships or boats. More precisely, the term trimaran is used for a ship or boat with three identical hulls of traditional shape. The other triple-hull ships are outrigger and tricore.

The trimaran has the widest range of interactions of wave systems generated by hulls at speed. The interactions can be favorable or unfavorable, depending on relative hull arrangement and speed. No authentic trimarans exist. Model test results and corresponding simulations provide estimates on the power of the full-scale ships. The calculations show possible advantages in a defined band of relative speeds.

A new type of super-fast vessel, the wave-piercing trimaran (WPT) is known as an air-born unloaded (up to 25% of displacement) vessel,[clarification needed] that can achieve twice the speed with a relative power.

Four-hull

The term quadrimaran is used for four-hulled vessels.

Five-hull

The term pentamaran is used for five-hulled vessels. The M80 Stiletto is a pentamaran.

Small waterplane area

1) SWATH ; each hull consists of the under-water volume (gondola or under-water volume or pontoon) and one long strut; the type is named after the first built ship: duplus

2) SWATH trisec two short struts on each hull;

3) tricore: triple-hull SWA ship with identical hulls

4) SWA with two outriggers

5) conventional central hull and SWA outriggers

6) a SWA monohull with foils

Hulls with beam designs that are narrower at the water surface (waterplane) than below can be classified as hulls with decreased or small waterplane area. More often the term small waterplane area hull means a hull with an underwater gondola and strut(s) that connect the gondola to the above-water platform. Any ship employing such hulls qualifies.

Any twin-hull SWA ship is called a small waterplane area twin hull (SWATH). A SWATH with one long strut on each hull is called a duplus (named after the first drilling ship of this type). The duplus is the most common type of SWA ships built.

A trisec is a SWATH ship with two struts on each gondola. A trisec can have a minimal waterplane area and minimal motions in waves, resulting in more effective motion control.

A triple-hull SWA ship is called a tricore, regardless of the number of struts. The term applies to ship with three identical SWA hulls. There are no built tricores, but towing tests of models show the possibility of sufficient advantage from a power point of view in defining band of the relative speeds.

Outrigger ships can employ SWA main hull and/or outriggers .

Characteristics

Many traits differentiate multihulls from monohulls along several axes.

Physical

Multihulls have a broader variety of hull and payload geometries. They have a relatively large beam, deck area (upper and inner), above-water capacity, shallower draft (allowing operation in shallower water).

Stability

The Austronesians discovered that round logs tied together into a raft don't roll, or capsize as easily as a single log. Hollowing out the logs increased buoyancy (increasing payload) while preserving stability. However, this requires a lot of work and it has increased drag and weight.

Separating two logs by a pair of cross-members called akas achieved the increased stability at lower weight and less effort. Covering the intervening distance with a platform provides stability similar to a raft.

Multihulls feature reduced roll and yaw (equivalent pitch motion) with transverse stability (depends on transverse clearance) comparable to or greater than longitudinal stability. This reduced motion reduces seasickness and allows for more efficient solar energy collection and radar operation. They offer more effective motion mitigation systems (SWA ships), reduced wave resistance and towing resistance by controlling hull aspect ratio (for twin-hulls) and optimizing the interference between each hull's wave systems (triple-hulls).

The inertia of a (heavier) monohull will drive it after the wind drops, while a (lighter) multihull requires wind. Monohulls can push through waves that a multihull must pass over. Multihulls are more prone towards hobby horsing especially when lightly loaded and of short overall length.

Weight stabilized

Other cultures stabilized their watercraft by filling the bottom with rocks and other ballast. The practice can be traced back to the Romans, Phoenicians, Vikings and others. Modern ocean liners carry tons of ballast. Naval architects enssure that the center of gravity of their designs remains substantially below the metacenter. The low centre of gravity acts as a counterweight as the craft rotates around its centre of buoyancy, creating a restorative force as the craft deviates from its vertical position.

Safety

Multihulls feature greater seaworthiness vs monohulls with the same displacement. Most production multihulls are officially rated as unsinkable. Watertight above-water platforms with sections protected by water-tight bulkheads can prevent sinking if the hulls fail. They have increased reliability because the engines are on separate hulls. However, capsized monohulls may right themselves, pulled by the ballast. Multihulls do not and larger vessels may require a crane. Their reduced weight and shallow draft make them unsuitable for use in icy waters.

Performance

Multihulls are substantially faster than monohulls of comparable size, in part because of their reduced weight, reduced draft and reduced waterline profile. However, their relatively greater total wetted area increases frictional resistance and total resistance at low speeds.[clarification needed]

Unlike monohulls multihulls can be designed to give very low wake at some speeds.[5][6]

Applications

Multihulls have more complicated conventional docking due to their wider beam. The beam requires a wider area for construction and dry dock and a larger haul-out ramp.

Sailboats and small vessels

Common multihull sailboats and small craft include proas, catamarans and trimarans.

The added space and stability are valued amenities for small boat users.

Multihull powerboats, usually catamarans (never proas) are used for racing and transportation. Speed, maneuverability, and space are the main factors for choosing multihulls.

- ... the weight of a multihull, of this length, is probably not much more than half the weight of a monohull of the same length and it can be sailed with less crew effort.[7]

Popular models

Multihulls are popular for racing, especially in Europe, New Zealand and Australia, and are somewhat popular for cruising in the Caribbean and South Pacific. They appear less frequently in the United States. Until the 1980s most multihull sailboats (except for beach cats) were built either by their owners or by boat builders. Since then companies have been selling mass-produced boats.

Small sailing catamarans are also called beach catamarans. The most recognized racing classes are the Hobie Cat 16, Formula 18 cats, A-cats, the current Olympic Nacra 17, the former Olympic multihull Tornado and New Zealand's Weta trimaran.

Power catamarans are becoming more common in Caribbean and Mediterranean international charter fleets.

Mega or super catamarans are those over 60 feet in length. These often receive substantial customization following the request of the owner. One builder is New Zealand's Pachoud Yachts.

Builders include Corsair Marine (mid-sized trimarans) and Privilege (large catamarans). The Seawind, Perry and Lightwave. The largest manufacturer of large multihulls is Fontaine-Pajot in France.

Powerboats range from small single pilot Formula 1s to large multi-engined or gas turbined power boats that are used in off-shore racing and employ 2 to 4 pilots.

Pioneers of multihull design include James Wharram (UK), Derek Kelsall (UK), Loch Crowther (Aust), Hedly Nicol (Aust), Malcolm Tennant (NZ), Jim Brown (USA), Arthur Piver (USA), Chris White (US), Ian Farrier (NZ) and LOMOcean (NZ).

Performance

In 1978, 101 years after catamarans like Amaryllis were banned from yacht racing[8] they returned the sport. This started with the victory of the trimaran Olympus Photo, skippered by Mike Birch in the first Route du Rhum. Thereafter, no open ocean race was won by a monohull. Winning times dropped by 70%, since 1978. Olympus Photo's 23-day 6 hr 58' 35" success dropped to Gitana 11's 7d 17h 19'6", in 2006.

See also

Notes

- ^ Dubrovsky, V (2004) Ships with Outriggers, Backbone Publishing Co, ISBN 0-9742019-0-1

- ^ Dubrovsky, V, Laykhovitsky, A (2001) Multi Hull Ships. Backbone Publishing Co. ISBN 97809644311-2-6

- ^ a b c d "A primer on proas". Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ "The Tridarka Raider". Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Tuck, E. O.; Lazauskas, L. (June 11, 1998), "Optimum Hull Spacing of a Family of Multihulls" (PDF), Applied Mathematics Department, The University of Adelaide: 38, retrieved 2016-01-15

- ^ J.W., Park; J.J., Kim; D.S., Kong (2001), Wu, You-Sheng; Zhou, Guo-Jun; Cui, Wei-Cheng (eds.), Numerical computation of ship's effective wake and its validation in large cavitation tunnel, Practical Design of Ships and Other Floating Structures: Eighth International Symposium - PRADS 2001, vol. 1, Elsevier, p. 1422, ISBN 9780080539355

- ^ Jim Howard; Charles J. Doane. Handbook of offshore cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising.

- ^ L. Francis Herreshoff. "The Spirit of the Times, November 24, 1877 (reprint)". Marine Publishing Co., Camden, Maine. Archived from the original on 2008-01-24.

References and Bibliography

- Jim Howard, Charles J. Doane. Handbook of offshore cruising: The Dream and Reality of Modern Ocean Cruising. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 280. ISBN 1-57409-093-3.

- C. A. Marchaj. Aero-Hydrodynamics of Sailing. Tiller Publishing. ISBN 1-888671-18-1.

- C. A. Marchaj. Sail Performance. McGraw Hill. p. 400. ISBN 0-07-141310-3.

- C. A. Marchaj. Seaworthiness:The Forgotten Factor. Tiller Publishing. p. 372. ISBN 1-888671-09-2.

- Gavin le Sueur. Multihull Seamanship. John Wiley & Sons. p. 144. ISBN 1-898660-31-X.

- Harvey, Derek, Multihulls for Cruising and Racing, Adlard Coles, London 1990, ISBN 0-7136-6414-2

External links

- The Multihull Offshore Cruising & Racing Association

- The UK Catamaran Racing Association

- The Multihull Yacht Club of Queensland (Australia)

- Multihull Boatbuilding Information / Community

- Articles and news on multihulls, profiles of boats, designers, yards, etc.

- Multihulls designer & builder

- International Sailing Federation

- The multihulls reference magazine

- The multihulls reference magazine (Australia)