Murder of James Bulger

James Bulger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James Patrick Bulger 16 March 1990 Liverpool, Merseyside, England |

| Died | 12 February 1993 (aged 2) Liverpool, England |

| Cause of death | Beating |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Murder victim |

| Parent(s) | Ralph Bulger Denise (now Fergus) |

James Patrick Bulger (16 March 1990[1] - 12 February 1993), a two-year-old child from Kirkby, Merseyside, England, was abducted, tortured and murdered. The perpetrators were two 10-year-old boys, Robert Thompson (born 23 August 1982) and Jon Venables, (born 13 August 1982).[2] Bulger disappeared on 12 February 1993 from the New Strand Shopping Centre, Bootle, while accompanying his mother. His mutilated body was found on a railway line in nearby Walton on 14 February. Thompson and Venables were charged on 20 February 1993 with the abduction and murder.

Thompson and Venables were found guilty of the murder of Bulger on 24 November 1993, making them the youngest convicted murderers in modern English history. They were sentenced to custody until they reached adulthood, initially until the age of 18, and were released on lifelong licence in June 2001. The case has prompted widespread debate on the issue of how to handle young offenders when they are sentenced or released from custody.[3]

The murder

CCTV evidence from the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle taken on 12 February 1993 showed Thompson and Venables casually observing children, apparently selecting a target.[4] The boys were playing truant from school, which they did regularly.[5] Throughout the day, Thompson and Venables were seen stealing various items including sweets, a troll doll, some batteries and a can of blue paint,[6] some of which were found at the murder scene.[7] It was later revealed by one of the boys that they were planning to find a child to abduct, lead it to the busy road alongside the mall, and push it into car traffic.[8]

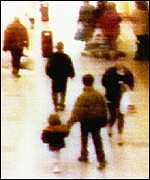

That same afternoon, James Bulger (often called "Jamie" by the press, although never by his family)[9], from nearby Kirkby, went with his mother Denise to the New Strand Shopping Centre. While inside a butcher's shop at around 3:40pm, Denise realised that her son had disappeared.[10] He had been left at the door of the shop while she placed an order, and was spotted by Thompson and Venables. They approached him and spoke to him, before taking him by the hand and leading him out of the precinct.[11] This moment was captured on a CCTV camera recording timestamped at 15:42.[12][13]

The boys took Bulger on a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) walk across Liverpool, leading him to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal where he was dropped on his head and suffered injuries to his face. The boys joked about pushing Bulger into the canal.[14][5] During the walk across Liverpool, the boys were seen by 38 people.[15] Bulger had a bump on his forehead and was crying, but most bystanders did nothing to intervene, assuming that he was a younger brother.[16][17] Two people challenged the older boys, but they claimed that Bulger was a younger brother or that he was lost and they were taking him to the local police station.[18] At one point, the boys took Bulger into a pet shop, from which they were ejected.[14] Eventually the boys led Bulger to a railway line near the disused Walton & Anfield railway station, close to Walton Lane police station and Anfield Cemetery, where they attacked him.[5]

At the trial it was established that at this location, one of the boys threw blue Humbrol modelling paint into Bulger's left eye.[9] They kicked him and hit him with bricks, stones and a 22-pound (10.0 kg) iron bar, described in court as a railway fishplate.[19][20][21] They placed batteries in his mouth.[22] Bulger suffered ten skull fractures as a result of the iron bar striking his head. Alan Williams, the case's pathologist, speculated that Bulger suffered so many injuries that none could be isolated as the fatal blow.[23] Police suspected that there was a sexual element to the crime, since Bulger's shoes, stockings, trousers and underpants had been removed. The pathologist's report read out in court stated that Bulger's foreskin had been manipulated.[24][19] When questioned about this aspect of the attack by detectives and the child psychiatrist Eileen Vizard, Thompson and Venables were reluctant to give details.[25][15]

Before they left him, the boys laid Bulger across the railway tracks and weighted his head down with rubble, in the hope that a train would hit him and make his death appear to be an accident. After Bulger's killers left the scene, his body was cut in half by a train.[26] Bulger's severed body was discovered two days later, on 14 February.[5] A forensic pathologist testified that he had died before he was struck by the train.[26]

The police quickly found low-resolution video images of Bulger's abduction from the Strand Shopping Centre by two unidentified boys.[5] As the circumstances surrounding the death became clear, tabloid newspapers denounced the people who had seen Bulger but had not intervened to aid Bulger as he was being taken through the city, as the "Liverpool 38". The railway embankment upon which his body had been discovered was flooded with hundreds of bunches of flowers.[27]

The crime created great anger in Liverpool. The family of one boy who was detained for questioning, but subsequently released, had to flee the city. The breakthrough came when a woman, on seeing slightly enhanced images of the two boys on national television, recognised Venables, who she knew had played truant with Thompson that day. She contacted police and the boys were arrested.[28] The fact that the boys were so young came as a shock to investigating officers, headed by Detective Superintendent Albert Kirby, of Merseyside Police. Early press reports and police statements had referred to Bulger being seen with "two youths" (suggesting that the killers were teenagers), the ages of the boys being difficult to ascertain from the images captured by CCTV.[28] When the case was featured on Crimewatch, the boys were estimated as being 12-14 years of age.[citation needed]

Forensic tests also confirmed that both boys had the same blue paint on their clothing as found on Bulger's body. Both had blood on their shoes; blood on Thompson's shoe was matched to Bulger through DNA tests.[29] The boys were charged with Bulger's murder on 20 February 1993,[5] and appeared at South Sefton Youth Court on 22 February 1993, when they were remanded in custody to await trial.[7][6][22]

Legal proceedings

In the aftermath of their arrest, and throughout the media accounts of their trial, the boys were referred to as 'Child A' (Thompson) and 'Child B' (Venables).[1] At the close of the trial, the judge ruled their names should be released (because of the nature of the murder and the public reaction), and they were identified along with lengthy descriptions of their lives and backgrounds. Public shock was compounded by the release, after the trial, of mug shots taken during questioning by police.

Five hundred protesters gathered at South Sefton Magistrates' Court during the boys' initial court appearances. The parents of the accused were moved to different parts of the country and assumed new identities following death threats from vigilantes.[28]

The full trial opened at Preston Crown Court on 1 November 1993,[5] conducted as an adult trial with the accused in the dock away from their parents, and the judge and court officials in legal regalia.[30] The boys denied the charges of murder, abduction and attempted abduction brought against them.[29] The attempted abduction charge related to an incident at the New Strand Shopping Centre earlier on 12 February 1993, the day of Bulger's death. Thompson and Venables had attempted to lead away another two-year-old boy, but had been prevented by the boy's mother.[11] Each boy sat in view of the court on raised chairs (so they could see out of the dock designed for adults) accompanied by two social workers. Although they were separated from their parents, they were within touching distance when their families attended the trial. News stories reported the demeanour of the defendants.[31] These aspects were later criticised by the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled in 1999 that they had not received a fair trial by being tried in public in an adult court.[5]

At the trial, the lead prosecution counsel Richard Henriques QC successfully rebutted the principle of doli incapax, which presumes that young children cannot be held legally responsible for their actions.[32] The child psychiatrist Dr. Eileen Vizard, who interviewed Thompson before the trial, was asked in court whether he would know the difference between right and wrong, that it was wrong to take a young child away from its mother, and that it was wrong to cause injury to a child. Vizard replied "If the issue is on the balance of probabilities, I think I can answer with certainty". Vizard also said that Thompson was suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder after the attack on Bulger. Dr. Susan Bailey, the Home Office forensic psychiatrist who interviewed Venables, said unequivocally that he knew the difference between right and wrong.[33] Thompson and Venables did not speak during the trial, and the case against them was based to a large extent on the more than 20 hours of tape recorded police interviews with the boys, which were played back in court.[32] The two boys, by then aged 11, were found guilty of Bulger's murder at Preston Crown Court on 24 November 1993, becoming the youngest convicted killers of the 20th century.[34] The judge Mr. Justice Morland told Thompson and Venables that they had committed a crime of "unparalleled evil and barbarity... In my judgment, your conduct was both cunning and very wicked."[35] The judge sentenced them to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure, with a recommendation that they should be kept in custody for "very, very many years to come",[7] recommending a minimum term of 8 years.[5] Shortly after the trial, Lord Taylor of Gosforth, the Lord Chief Justice, ordered that the two boys should serve a minimum of ten years,[5] which would have made them eligible for release in February 2003 at the age of twenty.

The editors of The Sun newspaper handed a petition bearing nearly 280,000 signatures to Home Secretary Michael Howard, in a bid to increase the time spent by both boys in custody.[36] This campaign was successful, and in July 1994 Howard announced that the boys would be kept in custody for a minimum of fifteen years,[36][37] meaning that they would not be considered for release until February 2008, by which time they would be twenty-five years of age.[5]

Lord Donaldson criticised Howard's intervention, describing the increased tariff as "institutionalised vengeance ... [by] a politician playing to the gallery".[5] The increased minimum term was overturned in 1997 by the House of Lords, who ruled that it was "unlawful" for the Home Secretary to decide on minimum sentences for offenders aged under 18.[38] The High Court and European Court of Human Rights have since ruled that, though the parliament may set minimum and maximum terms for individual categories of crime, it is the responsibility of the trial judge, with the benefit of all the evidence and argument from both prosecution and defence counsel, to determine the minimum term in individual criminal cases.[37]

The case led to public anguish, and concern at moral decay in Britain.[5] Tony Blair, then shadow Home Secretary, gave a speech in Wellingborough on 19 February, saying that "We hear of crimes so horrific they provoke anger and disbelief in equal proportions … These are the ugly manifestations of a society that is becoming unworthy of that name."[5] Prime Minister John Major said that "society needs to condemn a little more, and understand a little less".[5] The trial judge Mr. Justice Morland stated that exposure to violent videos might have encouraged the actions of Thompson and Venables, but this was disputed by David Maclean, the Minister of State at the Home Office at the time, who pointed out that police had found no evidence linking the case with "video nasties".[39] Some UK tabloid newspapers claimed that the attack on James Bulger was inspired by the film Child's Play 3, and campaigned for the rules on "video nasties" to be tightened.[40] Inspector Ray Simpson of Merseyside Police commented: "If you are going to link this murder to a film, you might as well link it to The Railway Children".[41] The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 clarified the rules on the availability of certain types of video material to children.[5][42]

Appeal and release

In 1999, lawyers for Thompson and Venables appealed to the European Court of Human Rights that the boys' trial had not been impartial, since they were too young to follow proceedings and understand an adult court. The European Court dismissed their claim that the trial was inhuman and degrading treatment, but upheld their claim they were denied a fair hearing by the nature of the court proceedings.[43][44] The European Court also held that Michael Howard's intervention had led to a "highly charged atmosphere", which resulted in an unfair judgment.[45] On 15 March 1999, the court in Strasbourg ruled by 14 votes to 5 that there had been a violation of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights regarding the fairness of the trial of Thompson and Venables, stating: "The public trial process in an adult court must be regarded in the case of an 11-year-old child as a severely intimidating procedure".[30]

In September 1999, Bulger's parents applied to the European Court of Human Rights, but failed to persuade the court that a victim of a crime has the right to be involved in determining the sentence of the perpetrator.[5][46]

The European Court case led to the new Lord Chief Justice, Lord Woolf, reviewing the minimum sentence. In October 2000, he recommended the tariff be reduced from ten to eight years,[5] adding that young offenders' institutions were a "corrosive atmosphere" for the juveniles.[47]

In June 2001, after a six-month review, the parole board ruled the boys were no longer a threat to public safety and could be released as their minimum tariff had expired in the February of that year. The Home Secretary David Blunkett approved the decision, and they were released within weeks.[48] They were given new identities and moved to secret locations under a "witness protection"-style action.[49]

Thompson and Venables were released on a life licence in June 2001, after serving eight years, when a parole hearing concluded that public safety would not be threatened by their rehabilitation.[50] The terms of their release include the following: They are not allowed to contact each other or Bulger's family. They are prohibited from visiting the Merseyside region.[51] Curfews may be imposed on them and they must report to probation officers. Breach of those rules would make them liable to be returned to prison. If they were deemed to be a risk to the public, they would be returned to prison.[52]

An injunction was imposed on the news media after the trial, preventing the publication of details about the boys. The injunction was kept in force following their release on parole, so their new identities and locations could not be published.[53][54][5] David Blunkett stated in 2001: "The injunction was granted because there was a real and strong possibility that their lives would be at risk if their identities became known".[52]

Subsequent events

The Manchester Evening News named the secure institutions in which the pair were housed, in possible breach of the injunction against publicity which had been renewed early in 2001. In December that year, the paper was fined £30,000 for contempt of court and ordered to pay costs of £120,000.[55]

The Guardian revealed that both boys had passed A-levels during their sentences. The paper also told how the Bulger family’s lawyers had consulted psychiatric experts in order to present the parole panel with a report which suggested that Thompson is an undiagnosed psychopath, citing his lack of remorse during his trial and arrest. The report was ultimately dismissed. However, his lack of remorse at the time, in stark contrast to Venables, led to considerable scrutiny from the parole panel. Upon release, both Thompson and Venables had lost all trace of their Liverpool accents.[56] In a psychiatric report prepared in 2000 prior to Venables' release, he was described as posing a "trivial" risk to the public and unlikely to reoffend. The chances of his successful rehabilitation were described as "very high".[57]

No significant publication or vigilante action against Thompson or Venables has occurred. Despite this, Bulger's mother, Denise, told how in 2004 she received a tip-off from an anonymous source that helped her locate Thompson. Upon seeing him, she was "paralysed with hatred" and was unable to confront him.[58]

In April 2007, documents released under the Freedom of Information Act confirmed that the Home Office had spent £13,000 on an injunction to prevent a foreign magazine from revealing the new identities of Thompson and Venables. [59] [60]

On 14 March 2008, an appeal to set up a Red Balloon Learner Centre in Merseyside in memory of James Bulger was launched by Denise Fergus, his mother, and Esther Rantzen.[61][62] A memorial garden in Bulger's memory was created in Sacred Heart Primary School in Kirkby. He would have been expected to attend this school had he not been murdered.[5]

Bulger's parents Ralph and Denise divorced in 1995, and Denise married Stuart Fergus in 1998.[63]

In March 2010, a call was made to raise the age of criminal responsibility in England from 10 to 12. Children's commissioner Maggie Atkinson said that the killers of James Bulger should have undergone "programmes" to help turn their lives around, rather than being prosecuted. The Ministry of Justice rejected the call, saying that children over the age of 10 knew the difference "between bad behaviour and serious wrongdoing".[64]

In April 2010, a 19-year-old man from the Isle of Man was given a three-month suspended prison sentence for claiming in a Facebook message that one of his former work colleagues was Robert Thompson. In passing sentence, Deputy High Bailiff Alastair Montgomery said that the teenager had "put that person at significant risk of serious harm" and in a "perilous position" by making the allegation.[65]

2010 imprisonment of Venables

On 2 March 2010, the Ministry of Justice revealed that Jon Venables had been returned to prison for an unspecified violation of the terms of his licence of release. Justice Secretary Jack Straw stated that Venables was returned to prison because of "extremely serious allegations", and stated that he was "unable to give further details of the reasons for Jon Venables' return to custody, because it was not in the public interest to do so."[66] Following the Sunday Mirror's claim on 7 March that Venables was returned to prison on suspected child pornography charges,[67][68][69] Straw repeated that premature disclosure of details of Venables's return to custody are not in the public interest, and that the "motivation throughout has been solely to ensure that some extremely serious allegations are properly investigated and that justice is done".[69] The Children's Secretary Ed Balls warned that some parts of the UK media were coming close to breaking the law, and stated : "If we responded to the desire for people to know the facts in public in a way which ends up prejudicing a legal case, we would look back and think we made very irresponsible decisions".[70] Straw revealed on BBC Radio 4's Today programme that due to the media and public pressure for details to be released, he would "make a judgment about if there's information – given that it's already out in the newspapers – we can confirm."[71]

In a statement to the House of Commons on 8 March 2010, Jack Straw reiterated that it was "not in the interest of justice" to reveal the reason why Venables had been returned to custody.[72] Baroness Butler-Sloss, the judge who made the decision to grant Venables anonymity in 2001, warned that he could be killed if his new identity was revealed.[73]

Bulger's mother Denise Fergus has said that she is angry that the Parole Board did not tell her that Venables had been returned to prison. Fergus has called for Venables' anonymity to be removed if he faces criminal charges over the allegations.[74] A spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice stated that there is a worldwide injunction against publication of either killers' location or new identity.[75]

The return to prison of Venables revived a false claim that a man from Fleetwood in Lancashire was Jon Venables. The claim was reported and dismissed in September 2005[76], but reappeared in March 2010 when it was circulated widely via SMS messages, Facebook and Twitter.[77] Chief Inspector Tracie O'Gara of Fleetwood Police stated: "An individual who was targeted four and a half years ago was not Jon Venables and now he has left the area".[78][79]

On 21 June 2010, it was reported that Venables had been charged with possession and distribution of indecent images of children. It was alleged that he downloaded 57 indecent images of children over a twelve month period to February 2010, and allowed other people to access the files through a peer-to-peer network. A court hearing of the case is scheduled for 23 July 2010, where he will face two charges under the Protection of Children Act 1978.[80][81]

Depictions of the case in the media

In June 2007 a computer game based on the TV series Law & Order, titled Law & Order: Double or Nothing (made in 2003), was withdrawn from stores in the UK following reports that it contained an image of Bulger. The image in question is the CCTV frame of Bulger being led away by his killers, Thompson and Venables. The scene in the game involves a computer-generated detective pointing out the picture, which is meant to represent a fictional child abduction that the player is then asked to investigate. Bulger's family complained, along with many others, and the game was subsequently withdrawn by its UK distributor, GSP. The game’s developer, Legacy Interactive (an American company), released a statement in which it apologised for the image's inclusion in the game; according to the statement, the image’s use was "inadvertent" and took place "without any knowledge of the crime, which occurred in the UK and was minimally publicised in the United States".[82]

In 2008, Swedish playwright Niklas Rådström used the interview transcripts from interrogations with the murderers and their families to recreate the story. His play, Monsters, opened to mixed reviews at the Arcola Theatre in London in May 2009.[83][84]

In August 2009, Australia's Seven Network used real footage of the abduction to promote its police show City Homicide. The use of the footage was criticised by Bulger's mother and Seven apologised.[85] A tie in with this saw the Sunrise co-hosts asking the rhetorical question of whether the killers were now living in Australia. When the question was answered on the 24 August 2009 edition, they used one minute and seven seconds to relate the Australian government's two-line denial that they had been settled in the country.[86]

A Hollyoaks storyline, set to begin in December 2009, was axed after the show gave Bulger's mother Denise Fergus a special screening. The storyline was to feature Loretta Jones and her friend Chrissy, who had been given new identities before arriving in the village, after being convicted of murdering a child at the age of 12.[87]

See also

{{{inline}}}

References

- ^ a b "The killers and the victims". CNN. 22 June 2001. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Thompson & Venables Recommendations as to Tariffs to the Secretary of State for Home Affairs". 26 October 2000. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Firth, Paul (3 March 2010). "A question of release and redemption as Bulger killer goes back into custody". Yorkshire Post. Johnston Press. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killers eligible for release". BBC Online. BBC. 26 October 2000. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Bulger, James Patrick (1990–1993), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2 Oct 2009. (Subscription Required)

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 1, The Video Tape". truTV.com. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b c ""Jon Venables & Robert Thompson"". MurderUK.com. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Blease, Stephen (23 February 2009). "Young know what is wrong". North-West Evening Mail. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Ferguson, Euan (9 February 2003). "Ten years on". London: The Guardian.

- ^ Sharratt, Tom (2 November 1993). "James Bulger 'battered with bricks'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Scott, Shirley. "Death of James Bulger: Pt 2, Abduction". truTV.com. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ CCTV: Does it work? BBC News. 13 August 2002.

- ^ Uncropped Mothercare CCTV still of the abduction, showing the timestamp at 15:42:32

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 3, The Trial". truTV.com. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ a b Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 6, The Trial". truTV.com. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Schoolboy tells of James Bulger's tears: Children said murder case victim was a brother, court told". London: The Independent. 9 November 1993. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ Pilkington, Edward (5 November 1993). "James Bulger in distress, say passers-by". London: The Guardian.

- ^ Coslett, Paul (4 December 2006). "Murder of James Bulger". BBC.

- ^ a b Foster, Jonathan (10 November 1993). "James Bulger suffered multiple fractures: Pathologist reveals two-year-old had 42 injuries including fractured skull". London: The Independent. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Sharratt, Tom (2 November 1993). "James Bulger murder". London: The Guardian.

- ^ Coslett, Paul (25 November 1993). "Lessons of an avoidable tragedy". London: The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Jamie Bulger". Snopes.

- ^ Foster, Jonathan (10 November 1993). "James Bulger suffered multiple fractures: Pathologist reveals ..." London: The Independent. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ Sereny, Gitta (6 February 1994). "Re-examining the evidence". London: The Independent. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Scott, Shirley. "Death of James Bulger: Pt 5, Robert Denies, Jon Cries". truTV.com. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ a b Sharratt, Tom (2 Nov 1993). "James Bulger 'battered with bricks'". London: Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Schmidt, William E. (24 February 1993). "Liverpool Tries to Reconcile Murder and a Boy Next Door". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Scott, Shirley (29 August 2009). "Death of James Bulger: Pt 4, Ten-Year-Old Suspects". truTV.com. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ a b Pilkington, Edward (11 Nov 1993). "Blood on boy's shoe 'was from victim'". London: Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Young suspects 'intimidated' by trial". BBC Online. BBC. 15 March 1999. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Harris, Paul (24 June 2001). "The secret meetings that set James's killers free". London: The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Foster, Jonathan (17 December 1999). "Bulger ruling: If the defendants could not talk about their crime, how could they conduct a defence?". London: The Independent. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Foster, Jonathan (2 December 1993). "Right and wrong paths to justice". London: The Independent. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ James Bulger case: timeline of key quotations Daily Telegraph 4 March 2010

- ^ Judgments - Reg. v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex parte V. and Reg. v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex parte T.

- ^ a b James Bulger killing: the case history of Jon Venables and Robert Thompson The Guardian 3 March 2010

- ^ a b "New sentencing rules: Key cases". BBC Online. BBC. 7 May 2003. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Outrage at call for Bulger killers' release". BBC. 28 October 1999.

- ^ Video link to Bulger murder disputed The Independent, 26 November 1993

- ^ Life after James The Guardian 6 February 2003

- ^ Demon ears The Guardian 21 March 1999

- ^ Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. Obscenity and Pornography and Videos - Section 90, Video recordings: suitability

- ^ BBC News 16 December 1999[1]. In a report dated 7 March 2010[2], the Daily Mirror incorrectly reported that the ECHR did affirm the claim of "inhuman and degrading treatment"

- ^ BBC News 16 December 1999, summary of the judgement of the ECHR [3]

- ^ "The Bulger case: chronology". London: The Guardian. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bates, Stephen (16 September 1999). "Bulger's mother puts her case". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Bulger killers 'released'". BBC Online. BBC. 22 June 2001. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Bulger statement in full at news.bbc.co.uk (accessed 23 April 2005)

- ^ Walker, Peter (22 January 2010). "Bulger killers prove child criminals can be rehabilitated". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Bulger killers 'face danger' at news.bbc.co.uk (accessed 23 April 2005)

- ^ Booth, Jenny (3 March 2010). "James Bulger mother: killer Jon Venables is 'where he belongs'". The Times. London: News Corporation. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Bulger killers released: what the home secretary said". BBC Online. BBC. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Young men, full of remorse, The Guardian, 27 October 2000

- ^ James Bulger murder at www.guardian.co.uk (accessed 25 April 2005)

- ^ Dyer, Clare (2001-12-05). "Paper fined for Bulger order breach". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ Harris & Bright (2001-06-24). "The secret meetings that set James's killers free". London: The Observer. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ^ Laing, Aislinn (10 March 2010). "Bulger killer Jon Venables posed 'trivial' risk to the public, said psychiatrist". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ Samuel, Katie (28 November 2008). "Jamie Bulger's mother 'tracks down killer'". London: The Times.

- ^ "£13K To Protect Bulger Killers' New IDs-Injunction". news.sky.com. 8 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ Barrett, David (9 April 2007). "£13,000 Spent protecting Bulger killers' identities". London: news.independent.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ Bulger 'refuge' appeal launched at news.bbc.co.uk (accessed 13 April 2008)

- ^ James Bulger memorial appeal launched at www.telegraph.co.uk (accessed 13 April 2008)

- ^ Pavia, Will (8 March 2010). "'It was like my son had been taken again'". London: The Times. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Calls to raise age of criminal responsibility rejected". BBC Online. BBC. 13 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Man sentenced for lying over James Bulger killer". BBC News. BBC. 23 April 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killer Venables faces 'extremely serious' claim". BBC Online. BBC. 6 March 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Jamieson, Alastair (7 March 2010). "James Bulger killer Jon Venables 'accused of child porn offences' - Telegraph". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ "Bulger killer Jon Venables jailed again 'for child porn'". www.news.com.au. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Text "News.com.au" ignored (help) - ^ a b "Jon Venables sent back to prison over child porn offence - mirror.co.uk". www.mirror.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Media Warned Over Bulger Killer's Identity Sky News 7 March 2010

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (8 March 2010). "Jon Venables: government may reveal details of prison recall". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

{{cite news}}: Text "UK news" ignored (help); Text "guardian.co.uk" ignored (help) - ^ Straw Will Not Reveal More On Bulger Killer Sky News 8 March 2010

- ^ Bulger killer Venables could be murdered, says ex-judge BBC News 8 March 2010

- ^ "Bulger's mother says Venables 'should be identified'". BBC Online. BBC. 6 March 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ Dodd, Vikram James Bulger killer back in prison guardian.co.uk 2010-03-02, Retrieved 2010-03-02

- ^ "I'm living in fear over 'child killer' rumours". Blackpool Gazette. 10 September 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Narain, Jaya (10 March 2010). "My ordeal at being mistaken for Jon Venables: Terror of young father accused of being Bulger killer". Daily Mail. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (10 March 2010). "Jon Venables: man wrongly accused of being James Bulger killer 'living in fear of vigilantes'". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "'I'm not Jon Venables'". Blackpool Gazette. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "Bulger killer Jon Venables faces child porn charges". BBC Online. BBC. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ "James Bulger killer Jon Venables is 'suspected paedophile'". Evening Standard. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ "Legacy Apologises For Law And Order Crime Photo". www.gamasutra.com. 21 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ^ Billington, Michael (9 May 2009). "Monsters". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McAlpine, Emma (15 May 2009) Review of Monsters at the Arcola Theatre

- ^ "Seven 'sorry' for Bulger ad" (PDF). The Age. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Rumour-Fuelled Ratings Chase". ABC. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ Todd, Ben (2009-11-15). "Channel 4 drops controversial Hollyoaks storyline ..." Daily Mail. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

External links

- Jon Venables has accepted the awfulness of his crime, said experts The Times, 10 March 2010

- James Bulger's mother meets Jack Straw BBC News, 11 March 2010

- How Edlington case follows course paved by Bulger trial BBC News, 22 January 2010

- Recollections from key people involved in the Bulger trial, ten years on. The Guardian, 6 February 2003.

- 'James would be 18 now - the pain of losing him will never go away' The Observer, 2 March 2008

- Balls criticises children's commissioner on Bulger view BBC News, 15 March 2010

- Fear and trauma in courtroom (psychiatrists' reports on Thompson and Venables) The Guardian, 17 December 1999

- Children's chief apologises for Bulger killers comment BBC News, 17 March 2010