Native American disease and epidemics

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

Although a variety of infectious diseases existed in the Americas in pre-Columbian times,[1] the limited size of the populations, smaller number of domesticated animals with zoonotic diseases, and limited interactions between those populations (as compared to areas of Eurasia and Africa) hampered the transmission of communicable diseases. One notable infectious disease that may be of American origin is syphilis.[1] Aside from that, most of the major infectious diseases known today originated in the Old World (Africa, Asia, and Europe). The American era of limited infectious disease ended with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas and the Columbian exchange of microorganisms, including those that cause human diseases. European infections and epidemics had major effects on Native American life in the colonial period and nineteenth century, especially.

Afro-Eurasia was a crossroad among many distant, different peoples separated by hundreds, if not thousands, of miles. But repeated warfare by invading populations spread infectious disease throughout the continent, as did trade, including the Silk Road. For more than 1,000 years travelers brought goods and infectious diseases from the East, where some of the latter had jumped from animals to humans. As a result of chronic exposure, many infections became endemic within their societies over time, so that surviving Europeans gradually developed some acquired immunity, although they were still vulnerable to pandemics and epidemics. Europeans carried such endemic diseases when they migrated and explored the New World.

Europeans often spread infectious diseases to Native Americans through trading and settlement efforts, and these could even be transmitted far from the sources and colonial settlements, including through exclusively Native American trading transactions. Warfare and enslavement also contributed to disease transmission. Because their populations were historically hygienic and had not been previously exposed to most of these infectious diseases, the Native American people rarely had individual or population acquired immunity and consequently suffered very high mortality. The numerous deaths disrupted Native American societies. This phenomenon is known as the virgin soil effect.[2]

Origin of the diseases

[edit]Most Old World diseases of known origin can be traced to Africa and Asia and were introduced to Europe over time. Smallpox originated in Africa or Asia,[3] plague in Asia,[4][5] cholera in Asia,[6][7] influenza in Asia,[8][9] malaria in Africa and Asia,[10][11][12] measles from Asian rinderpest,[13][14][15] tuberculosis in Asia,[16][17] yellow fever in Africa,[18] leprosy in Asia,[19] typhoid in Africa,[20] syphilis in America and Africa,[21] herpes in Africa,[22] zika in Africa.[23]

European contact

[edit]

The arrival and settlement of Europeans in the Americas resulted in what is known as the Columbian exchange. During this period European settlers brought many different technologies, animals, plants, and lifestyles with them, some of which benefited the indigenous peoples[citation needed]. Europeans also took plants and goods back to the Old World. Potatoes and tomatoes from the Americas became integral to European and Asian cuisines, for instance.[24]

But Europeans also unintentionally brought new infectious diseases, including among others smallpox, bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, the common cold, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, sexually transmitted diseases (with the possible exception of syphilis), typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis (although a form of this infection existed in South America prior to contact),[25] and pertussis.[26][27][28] Each of these resulted in sweeping epidemics among Native Americans, who had disability, illness, and a high mortality rate.[28] The Europeans infected with such diseases typically carried them in a dormant state, were actively infected but asymptomatic, or had only mild symptoms, because Europe had been subject for centuries to a selective process by these diseases. The explorers and colonists often unknowingly passed the diseases to natives.[24] The introduction of African slaves and the use of commercial trade routes contributed to the spread of disease.[29][30]

The infections brought by Europeans are not easily tracked, since there were numerous outbreaks and all were not equally recorded. Historical accounts of epidemics are often vague or contradictory in describing how victims were affected. A rash accompanied by a fever might be smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, or varicella, and many epidemics overlapped with multiple infections striking the same population at once, therefore it is often impossible to know the exact causes of mortality (although ancient DNA studies can often determine the presence of certain microbes).[31] Smallpox was the disease brought by Europeans that was most destructive to the Native Americans, both in terms of morbidity and mortality. The first well-documented smallpox epidemic in the Americas began in Hispaniola in late 1518 and soon spread to Mexico.[24] Estimates of mortality range from one-quarter to one-half of the population of central Mexico.[32]

Native Americans initially believed that illness primarily resulted from being out of balance, in relation to their religious beliefs. Typically, Native Americans held that disease was caused by either a lack of magical protection, the intrusion of an object into the body by means of sorcery, or the absence of the free soul from the body. Disease was understood to enter the body as a natural occurrence if a person was not protected by spirits, or less commonly as a result of malign human or supernatural intervention.[33] For example, Cherokee spiritual beliefs attribute disease to revenge imposed by animals for killing them.[34] In some cases, disease was seen as a punishment for disregarding tribal traditions or disobeying tribal rituals.[35] Spiritual powers were called on to cure diseases through the practice of shamanism.[36] Most Native American tribes also used a wide variety of medicinal plants and other substances in the treatment of disease.[37]

Environmental Changes and New Diseases

[edit]The resilience of indigenous people was quite weakened by Europeans’ colonization attempts which eventually led to environmental changes. They introduced new crops and livestock like pigs, and it influenced local ecosystems and brought new diseases. For example, this can be seen in the outbreaks when Christopher Columbus, in 1493, traveled to the Americas, island of Hispaniola. In there, the excess number of pigs contributed to the creation of influenza epidemic. This was the disease that contributed to the vast decline of the population throughout the history, and thus influenza may have become an endemic disease, spreading endlessly in the region due to the environmental changes brought by European colonization.

Forced Settlements and Disease Spread

[edit]European colonization also had its influence on populations by the forced settlements that further exposed them to diseases. The colonial policy of Spanish called “congregación” was a distinguished factor in the spread of disease. The requirements of this settlement required people to leave their traditional homes and move into new land that are often run by Franciscan missionaries. Under this policy, forced settlements not only disrupted their traditional way of life but also created environments where diseases could spread easily.

Moreover, in Florida, Spanish settlers forced indigenous groups into strictly controlled settlements. Since the early 16th century, these people were exposed to new diseases brought by Europeans, including smallpox, measles and typhus. A mix of involuntarily relocations and European-imposed changes to agriculture and resolution patterns also created ideal conditions for the spread of infectious diseases, leading to catastrophic declines in the number of the population.[38]

Smallpox

[edit]Smallpox was lethal to many Native Americans, resulting in sweeping epidemics and repeatedly affecting the same tribes. After its introduction to Mexico in 1519, the disease spread across South America, devastating indigenous populations in what are now Colombia, Peru and Chile during the sixteenth century. The disease was slow to spread northward due to the sparse population of the northern Mexico desert region. It was introduced to eastern North America separately by colonists arriving in 1633 to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and local Native American communities were soon struck by the virus. It reached the Mohawk nation in 1634,[39] the Lake Ontario area in 1636, and the lands of other Iroquois tribes by 1679.[40] Between 1613 and 1690 the Iroquois tribes living in Quebec suffered twenty-four epidemics, almost all of them caused by smallpox.[41] By 1698 the virus had crossed the Mississippi, causing an epidemic that nearly obliterated the Quapaw Indians of Arkansas.[35]

The disease was often spread during war. John McCullough, a Delaware captive since July 1756, who was then 15 years old, wrote that the Lenape people, under the leadership of Shamokin Daniel, "committed several depredations along the Juniata; it happened to be at a time when the smallpox was in the settlement where they were murdering, the consequence was, a number of them got infected, and some died before they got home, others shortly after; those who took it after their return, were immediately moved out of the town, and put under the care of one who had the disease before."[42][43][44][45]

By the mid-eighteenth century the disease was affecting populations severely enough to interrupt trade and negotiations. Thomas Hutchins, in his August 1762 journal entry while at Ohio's Fort Miami, named for the Mineamie people, wrote:

The 20th, The above Indians met, and the Ouiatanon Chief spoke in behalf of his and the Kickaupoo Nations as follows: "Brother, We are very thankful to Sir William Johnson for sending you to enquire into the State of the Indians. We assure you we are Rendered very miserable at Present on Account of a Severe Sickness that has seiz'd almost all our People, many of which have died lately, and many more likely to Die..." The 30th, Set out for the Lower Shawneese Town and arriv'd 8th of September in the afternoon. I could not have a meeting with the Shawneese the 12th, as their People were Sick and Dying every day.[46]

On June 24, 1763, during the siege of Fort Pitt, as recorded in his journal by fur trader and militia captain William Trent, dignitaries from the Delaware tribe met with British officials at the fort, warned them of "great numbers of Indians" coming to attack the fort, and pleaded with them to leave the fort while there was still time. The commander of the fort, Simeon Ecuyear, refused to abandon the fort. Instead, Ecuyear gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one piece of linen that were believed to have been in contact with smallpox-infected individuals, to the two Delaware emissaries Turtleheart and Mamaltee, allegedly in the hope of spreading the deadly disease to nearby tribes, as attested in Trent's journal.[47][48][49][50][51] The dignitaries were met again later and they seemingly hadn't contracted smallpox.[52] A relatively small outbreak of smallpox had begun spreading earlier that spring, with a hundred dying from it among Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764.[52] The effectiveness of the biological warfare itself remains unknown, and the method used is inefficient compared to airborne transmission.[53][54]

21st-century scientists such as V. Barras and G. Greub have examined such reports. They say that smallpox is spread by respiratory droplets in personal interaction, not by contact with fomites, such objects as were described by Trent. The results of such attempts to spread the disease through objects are difficult to differentiate from naturally occurring epidemics.[55][56]

Gershom Hicks, held captive by the Ohio Country Shawnee and Delaware between May 1763 and April 1764, reported to Captain William Grant of the 42nd Regiment "that the Small pox has been very general & raging amongst the Indians since last spring and that 30 or 40 Mingoes, as many Delawares and some Shawneese Died all of the Small pox since that time, that it still continues amongst them".[57]

19th century

[edit]In 1832 President Andrew Jackson signed Congressional authorization and funding to set up a smallpox vaccination program for Indian tribes. The goal was to eliminate the deadly threat of smallpox to a population with little or no immunity, and at the same time exhibit the benefits of cooperation with the government.[58] In practice there were severe obstacles. The tribal medicine men launched a strong opposition, warning of white trickery and offering an alternative explanation and system of cure. Some taught that the affliction could best be cured by a sweat bath followed by a rapid plunge into cold water.[59][60] Furthermore the vaccines often lost their potency when transported and stored over long distances with primitive storage facilities. It was too little and too late to avoid the great smallpox epidemic of 1837 to 1840 that swept across North America west of the Mississippi, all the way to Canada and Alaska. Deaths have been estimated in the range of 100,000 to 300,000, with entire tribes wiped out. Over 90 percent of the Mandans died.[61][62][63]

In the mid to late nineteenth century, at a time of increasing European-American travel and settlement in the West, at least four different epidemics broke out among the Plains tribes between 1837 and 1870.[26] When the Plains tribes began to learn of the "white man's diseases", many intentionally avoided contact with them and their trade goods. But the lure of trade goods such as metal pots, skillets, and knives sometimes proved too strong. The Indians traded with the white newcomers anyway and inadvertently spread disease to their villages.[64] In the late 19th century, the Lakota Indians of the Plains called the disease the "rotting face sickness".[35][64]

The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic, which was brought from San Francisco to Victoria, devastated the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, with a death rate of over 50% for the entire coast from Puget Sound to Southeast Alaska.[65] In some areas the native population fell by as much as 90%.[66][67] Some historians have described the epidemic as a deliberate genocide because the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Colony of British Columbia could have prevented the epidemic but chose not to, and in some ways facilitated it.[66][68]

Effect on population numbers

[edit]

Many Native American tribes suffered high mortality and depopulation, averaging 25–50% of the tribes' members dead from disease. Additionally, some smaller tribes neared extinction after facing a severely destructive spread of disease.[26]

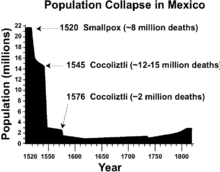

A specific example was what followed Cortés' invasion of Mexico. Before his arrival, the Mexican population is estimated to have been around 25 to 30 million. Fifty years later, the Mexican population was reduced to 3 million, mainly by infectious disease. A 2018 study by Koch, Brierley, Maslin and Lewis concluded that an estimated "55 million indigenous people died following the European conquest of the Americas beginning in 1492."[69] Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during the Cocoliztli epidemics in New Spain have ranged from 5 to 15 million people,[70] making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time.[71] By 1700, fewer than 5,000 Native Americans remained in the southeastern coastal region of the United States.[28] In Florida alone, an estimated 700,000 Native Americans lived there in 1520, but by 1700 the number was around 2,000.[28]

Some 21st-century climate scientists have suggested that a severe reduction of the indigenous population in the Americas and the accompanying reduction in cultivated lands during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries may have contributed to a global cooling event known as the Little Ice Age.[69][72]

The loss of the population was so high that it was partially responsible for the myth of the Americas as "virgin wilderness". By the time significant European colonization was underway, native populations had already been reduced by 90%. This resulted in settlements vanishing and cultivated fields being abandoned. Since forests were recovering, the colonists had an impression of a land that was an untamed wilderness.[73]

Disease had both direct and indirect effects on deaths. High mortality meant that there were fewer people to plant crops, hunt game, and otherwise support the group. Loss of cultural knowledge transfer also affected the community as vital agricultural and food-gathering skills were not passed on to survivors. Missing the right time to hunt or plant crops affected the food supply, thus further weakening the community and making it more vulnerable to the next epidemic. Communities under such crisis were often unable to care for people who were disabled, elderly, or young.[28]

In summer 1639, a smallpox epidemic struck the Huron natives in the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes regions. The disease had reached the Huron tribes through French colonial traders from Québec who remained in the region throughout the winter. When the epidemic was over, the Huron population had been reduced to roughly 9,000 people, about half of what it had been before 1634.[74] The Iroquois people, generally south of the Great Lakes, faced similar losses after encounters with French, Dutch and English colonists.[28]

During the 1770s, smallpox killed at least 30% (tens of thousands) of the Northwestern Native Americans.[75][76] The smallpox epidemic of 1780–1782 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[77]

By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[78] The Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1839 reported on the casualties of the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic: "No attempt has been made to count the victims, nor is it possible to reckon them in any of these tribes with accuracy; it is believed that if [the number 17,200 for the upper Missouri River Indians] was doubled, the aggregate would not be too large for those who have fallen east of the Rocky Mountains."[79]

Historian David Stannard asserts that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and 'unintended consequence' of human migration and progress." He says that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable", but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[80] Historian Andrés Reséndez says that evidence suggests "among these human factors, slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, rather than diseases such as smallpox, influenza and malaria.[81]

Cholera

[edit]Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection transmitted through ingesting water or food contaminated with the bacteria vibrio cholerae.[82] Cholera was specific to Asia until 1817. By 1829, Cholera was documented in North America and quickly spread throughout regions in rural and urban America.[83] Up until the 20th century, the origin of Cholera was unknown. Symptoms of Cholera are known for their fast and advanced nature.[84] Symptoms of Cholera include nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting which contribute to dehydration, erratic heartbeat, and shriveled skin.[85] These symptoms contributed to Cholera's high mortality rate.[86] Some of the most significant Cholera outbreaks occurred during the 1800s (when the cause was still unknown). Cholera affected many communities throughout the United States, especially communities that lived in unsanitary conditions.[87] One population that was affected by water-borne disease such as Cholera, were Native Americans. Even though Cholera changed every American's life, the nature of Cholera and how it spread through communities had large impacts on indigenous communities throughout history.

Cholera in the United States

[edit]Cholera reached the United States in 1829 when immigrants came to America searching for new jobs and opportunities.[83] Cholera, because it mostly resulted from poor hygiene and filthy conditions, disproportionately affects lower-income populations living in unsanitary conditions. Native Americans who lived their lives on reservations found themselves drinking water that was contaminated with vibrio cholerae.[88] Poor drinking water and sanitary conditions contributed to the widespread spread of Cholera cases in Native communities.[89]

Cholera Epidemic of 1832

[edit]One of the most notable Cholera epidemics happened in 1832. In May 1832, an immigrant ship with Asiatic Cholera landed in Quebec.[90] Cholera spread quickly from the northern ports of Quebec down to the Hudson and Lower Manhattan.[91] The rapid spread of Cholera from northern ports marked the onset of epidemics in major cities such as New York. The Epidemic of 1832 has been referred to by historians as the plague of the 19th century.[92] America, up until this point, was not very familiar with the effects of widespread diseases. Cholera is known for its ability to quickly spread and flourish in every environment. Because of this Cholera was found in almost every part of the country during this period.

Cholera's impact during the 1832 epidemic was particularly profound on indigenous communities. Cholera spread to Native populations in 1832 through waterways. Cholera was a problem all over but more prevalent in communities situated near water.[93] Native American communities were more prevalent near sources of water because they wanted to have an accessible source of drinking water[93] Unfortunately, Cholera (bacterium cholerae) spread rapidly through these areas. Increasing the community's chances of being infected. Some communities had more severe Cholera outbreaks than others. The Lakota tribe, for instance, had a major Cholera outbreak and demographic devastation due to the disposal of waste in the Great Lakes, a water source they consistently used for drinking.[94] Cholera outbreaks were more devastating primarily because indigenous communities had little forms of water filtration and lacked immunity to water-borne diseases.[95] Due to a lack of immunity to water-borne disease, Native Americans suffered from higher mortality rates[96] Lack of immunity and exposure to bodies of water contaminated by cholera contributed to higher mortality rates in indigenous communities during the 1832 epidemic.

Trail of Tears

[edit]The Trail of Tears was the forced relocation of Native American tribes in the 1830s from Eastern Woodlands to the west of the Mississippi River.[97] This relocation ordered by the government primarily targeted “the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole” nations [97] Approximately 100,000 native Americans were removed from their families and 15,000 died during the removal and journey west.[97] The journey west consisted of 5,045 miles across nine states.[97] Many people lost their lives on this rigorous forced journey. Cholera was one of the reasons for the deaths of Native Americans during the Trail of Tears. Traveling by steamboat was a common way to travel and cholera was present in the waterways used by the steamboats.[98] It is estimated that 5,000 Native Americans died of cholera on this journey to areas west of the Mississippi.[97]

1850 Cholera Outbreak

[edit]The deadliest cholera outbreak happened in the 1850s[99] Cholera outbreaks during the 1850s were widespread, but cases were highly concentrated in areas with dense populations. The outbreak lasted from 1852 to 1860. 23,000 deaths were recorded in Britain alone[100] The outbreak in Britain led to immigrants fleeing their homes and immigrating to America. This started the third significant and most deadly spread of cholera in America. This outbreak spread through the Mississippi River. The spread through the Mississippi reached communities in St. Louis to New Orleans.[citation needed] Many Native American communities contracted Cholera when they used the Mississippi River for transportation. Native American death tolls reached record highs during the outbreak in the 1850s. An example of a moment that became a major transmission event for cholera among tribes was the annual Kiowa Sun Dance. Several tribes were in attendance including the Osage, Comanche, Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Apache.[98] Sarah Keyes, a historian who specializes in the 19th century wrote that “The disease was demographically devastating for many Native nations of the plains. For instance, by the end of the 1854 epidemic the Pawnee had lost as much as 25 percent of their population” (Keyes) [98] The Pawnee tribe was not the only tribe that was devastated by Cholera in the 1850s. Cholera was highly transmissible and led to outbreaks among multiple tribes and indigenous communities.[101] The population of many Native American tribes and communities were forever changed after the 1850 pandemic.

Cholera in Modern Era Native American Life

[edit]It is true that health disparities and cholera still exist today, specifically in native american communities. Today there have been a reported 1.3 to 2 million cases across the world and 21,000 to 14,300 deaths (WHO)[102] Limited access to clean water and poor healthcare infrastructure contribute to the Cholera cases and deaths we see today. A majority of the people who contract these diseases are from indigenous communities in the United States. Indigenous communities have been more susceptible to diseases like Cholera because of limited access to clean water. Today, recent studies have shown that one in 10 Indigenous Americans lack access to safe tap water or basic sanitation – without which a host of health conditions including Covid-19, diabetes, and gastrointestinal disease are more likely.[103] Activists and tribal governments have spoken with public health agencies and organizations to address these healthcare disparities. Many activists have organized protests and discussions with government and health officials. Winona LaDuke is an example of one activist who has been trying to promote a sustainable and healthy environment and land for Native Americans on reservations. She has been involved in the White Earth Land Recovery Project which tries to address environmental inequities hurting Native American communities today.[104] Even though Cholera pandemics are no longer a concern, unhealthy water conditions on reservations still present many diseases and issues for indigenous communities today.

Disability

[edit]Epidemics killed a high portion of people with disabilities and also resulted in numerous people with disabilities. The material and societal realities of disability for Native American communities were tangible.[28] Scarlet fever could result in blindness or deafness, and sometimes both.[28] Smallpox epidemics led to blindness and depigmented scars. Many Native American tribes prided themselves in their appearance, and the resulting skin disfigurement of smallpox deeply affected them psychologically. Unable to cope with this condition, tribe members were said to have committed suicide.[105]

Archaeology of disease

[edit]Paleo-scientists can see the expression of disease by looking at its effect on bones, yet this offers a limited view. Most common infectious diseases, such as those caused by microorganisms like staphylococcus and streptococcus cannot be seen in the bones. Tuberculosis and the two forms of syphilis are considered rare and their diagnosis via osteological analysis is controversial. To understand health at the community level, scientists and health experts look at diet, the incidence and prevalence of infections, hygiene and waste disposal.[citation needed] Most diseases came to the Americas from Europe and Asia. One exception is syphilis, which originated in the Americas before 1492.[106][107] A form of tuberculosis has also been identified in pre-Columbian populations, by bacterial genome sequences collected from human remains in Peru, and was probably transmitted to humans through seal hunting.[108]

See also

[edit]- Little Ice Age

- New World syndrome

- Alcohol and Native Americans

- Native American health

- Environmental racism

- Impact of Old World diseases on the Maya

- History of smallpox in Mexico

- Cocoliztli epidemics

- 1918 Spanish flu pandemic

- COVID-19 pandemic in the Navajo Nation

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Native American tribes and tribal communities

General:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Martin, Debra L; Goodman, Alan H (January 2002). "Health conditions before Columbus: paleopathology of native North Americans". Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.1.65. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071659. PMID 11788545.

- ^ Crosby, Alfred W. (1976), "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America", The William and Mary Quarterly, 33 (2), Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 289–299, doi:10.2307/1922166, JSTOR 1922166, PMID 11633588

- ^ Thèves, Catherine; Crubézy, Eric; Biagini, Philippe (2016-08-12). Drancourt, Michel; Raoult, Didier (eds.). "History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (4). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PoH-0004-2014. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27726788.

- ^ Achtman, M.; Zurth, K.; Morelli, G.; Torrea, G.; Guiyoule, A.; Carniel, E. (1999-11-23). "Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (24): 14043–14048. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9614043A. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.24.14043. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 24187. PMID 10570195.

- ^ McNally, Alan; Thomson, Nicholas R.; Reuter, Sandra; Wren, Brendan W. (2016). "'Add, stir and reduce': Yersinia spp. as model bacteria for pathogen evolution". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 14 (3): 177–190. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2015.29. ISSN 1740-1534. PMID 26876035.

- ^ Lippi, Donatella; Gotuzzo, Eduardo; Caini, Saverio (2016). "Cholera". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (4). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PoH-0012-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27726771.

- ^ "Cholera - WHO Fact sheets".

- ^ Morens, David M.; Taubenberger, Jeffery K.; Folkers, Gregory K.; Fauci, Anthony S. (2010-12-15). "Pandemic influenza's 500th anniversary". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 51 (12): 1442–1444. doi:10.1086/657429. ISSN 1537-6591. PMC 3106245. PMID 21067353.

- ^ Threats, Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial; Knobler, Stacey L.; Mack, Alison; Mahmoud, Adel; Lemon, Stanley M. (2005), "The Story of Influenza", The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 2024-05-29

- ^ Lee, Kim-Sung; Divis, Paul C. S.; Zakaria, Siti Khatijah; Matusop, Asmad; Julin, Roynston A.; Conway, David J.; Cox-Singh, Janet; Singh, Balbir (2011). "Plasmodium knowlesi: reservoir hosts and tracking the emergence in humans and macaques". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (4): e1002015. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002015. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 3072369. PMID 21490952.

- ^ Liu, Weimin; Li, Yingying; Shaw, Katharina S.; Learn, Gerald H.; Plenderleith, Lindsey J.; Malenke, Jordan A.; Sundararaman, Sesh A.; Ramirez, Miguel A.; Crystal, Patricia A.; Smith, Andrew G.; Bibollet-Ruche, Frederic; Ayouba, Ahidjo; Locatelli, Sabrina; Esteban, Amandine; Mouacha, Fatima (2014). "African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax". Nature Communications. 5: 3346. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3346L. doi:10.1038/ncomms4346. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4089193. PMID 24557500.

- ^ Liu, Weimin; Li, Yingying; Learn, Gerald H.; Rudicell, Rebecca S.; Robertson, Joel D.; Keele, Brandon F.; Ndjango, Jean-Bosco N.; Sanz, Crickette M.; Morgan, David B.; Locatelli, Sabrina; Gonder, Mary K.; Kranzusch, Philip J.; Walsh, Peter D.; Delaporte, Eric; Mpoudi-Ngole, Eitel (2010). "Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas". Nature. 467 (7314): 420–425. Bibcode:2010Natur.467..420L. doi:10.1038/nature09442. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 2997044. PMID 20864995.

- ^ Berche, Patrick (2022-09-01). "History of measles". La Presse Médicale. History of modern pandemics. 51 (3): 104149. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2022.104149. ISSN 0755-4982. PMID 36414136.

- ^ Roeder, Peter; Mariner, Jeffrey; Kock, Richard (2013-08-05). "Rinderpest: the veterinary perspective on eradication". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1623): 20120139. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0139. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3720037. PMID 23798687.

- ^ Tounkara, K.; Nwankpa, N. (2017). "Rinderpest experience". Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics). 36 (2): 569–578. doi:10.20506/rst.36.2.2675. ISSN 0253-1933. PMID 30152462.

- ^ Barberis, I.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Galluzzo, L.; Martini, M. (2017). "The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 58 (1): E9–E12. ISSN 1121-2233. PMC 5432783. PMID 28515626.

- ^ Buzic, I.; Giuffra, V. (2020). "The paleopathological evidence on the origins of human tuberculosis: a review". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 61 (1 Suppl 1): E3–E8. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2020.61.1s1.1379. ISSN 2421-4248. PMC 7263064. PMID 32529097.

- ^ Gianchecchi, Elena; Cianchi, Virginia; Torelli, Alessandro; Montomoli, Emanuele (2022). "Yellow Fever: Origin, Epidemiology, Preventive Strategies and Future Prospects". Vaccines. 10 (3): 372. doi:10.3390/vaccines10030372. ISSN 2076-393X. PMC 8955180. PMID 35335004.

- ^ Monot, Marc; Honoré, Nadine; Garnier, Thierry; Araoz, Romulo; Coppée, Jean-Yves; Lacroix, Céline; Sow, Samba; Spencer, John S.; Truman, Richard W.; Williams, Diana L.; Gelber, Robert; Virmond, Marcos; Flageul, Béatrice; Cho, Sang-Nae; Ji, Baohong (2005-05-13). "On the origin of leprosy". Science. 308 (5724): 1040–1042. doi:10.1126/science/1109759. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 15894530.

- ^ Roumagnac, Philippe; Weill, François-Xavier; Dolecek, Christiane; Baker, Stephen; Brisse, Sylvain; Chinh, Nguyen Tran; Le, Thi Anh Hong; Acosta, Camilo J.; Farrar, Jeremy; Dougan, Gordon; Achtman, Mark (2006-11-24). "Evolutionary History of Salmonella Typhi". Science. 314 (5803): 1301–1304. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1301R. doi:10.1126/science.1134933. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 2652035. PMID 17124322.

- ^ Rothschild, B. M. (2005-05-15). "History of Syphilis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (10): 1454–1463. doi:10.1086/429626. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 15844068.

- ^ Wertheim, Joel O.; Smith, Martin D.; Smith, Davey M.; Scheffler, Konrad; Kosakovsky Pond, Sergei L. (2014). "Evolutionary Origins of Human Herpes Simplex Viruses 1 and 2". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (9): 2356–2364. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu185. ISSN 1537-1719. PMC 4137711. PMID 24916030.

- ^ "Zika virus". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ a b c Francis, John M. (2005). Iberia and the Americas culture, politics, and history: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Bos, Kirsten I.; Harkins, Kelly M.; Herbig, Alexander; Coscolla, Mireia; et al. (20 August 2014). "Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis". Nature. 514 (7523): 494–7. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..494B. doi:10.1038/nature13591. PMC 4550673. PMID 25141181.

- ^ a b c Waldman, Carl (2009). Atlas of the North American Indian. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 206.

- ^ Rossi, Ann (2006). Two Cultures Meet: Native American and European. National Geographic Society. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-7922-8679-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nielsen, Kim (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2204-7.

- ^ Rodrigo Barquera; Johannes Krause; AJ Zeilstra; Petra Mader (May 9, 2020). "Slavery entailed the spread of epidemics". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.

- ^ "The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the Introduction of Human Diseases: The Case of Schistosomiasis - Africa Atlanta 2014 Publications". leading-edge.iac.gatech.edu.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ Hays, J. N.. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. United Kingdom: ABC-CLIO, 2005.

- ^ Vogel, Virgil J. American Indian Medicine. University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

- ^ John Phillip. A law of blood; the primitive law of the Cherokee nation. New York: Northern Illinois University Press, 1970.

- ^ a b c Robertson, R. G. Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian. Caxton Press, 2001.ISBN 0870044974

- ^ Lyon, William S. (1998). Encyclopedia of Native American Healing. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31735-0.

- ^ Moerman, Daniel E. (July 16, 1998). Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-453-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grob, Gerald (2006). The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America. pp. 26–69.

- ^ Dutch Children's Disease Kills Thousands of Mohawks Archived 2007-12-17 at the Wayback Machine. Paulkeeslerbooks.com

- ^ Duffy, John (1951). "Smallpox and the Indians in the American Colonies". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 25 (4): 324–341. JSTOR 44443622. PMID 14859018. ProQuest 1296241519.

- ^ Ramenofsky, Ann Felice (1987). Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0997-6.[page needed]

- ^ McCullough, John: The Captivity of John McCullough/ Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892)Journal of Captain Simeon Ecuyer, Entry June 2, 1763

- ^ McCullough, John: http://The Captivity of John McCullough Personally written after eight years of captivity. Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dixon, David, Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America (pg. 155)

- ^ Hanna, Charles A.: The wilderness trail: or, the ventures and adventures of the Pennsylvania traders on the Allegheny path, with some new annals of the old West, and the records of some strong men and some bad ones (1911) pg.366

- ^ Ewald, Paul W. (2000). Plague Time: How Stealth Infections Cause Cancer, Heart Disease, and Other Deadly Ailments. New York: Free. ISBN 978-0-684-86900-1.

- ^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Fort Pitt and letters from the frontier (1892). Captain Simeon Ecuyer's Journal: Entry of June 24,1763

- ^ Fenn, Elizabeth A. (2000). "Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst". The Journal of American History. 86 (4): 1552–1580. doi:10.2307/2567577. JSTOR 2567577. PMID 18271127. ProQuest 224890556.

- ^ Flight, Colette (17 February 2011). "Silent Weapon: Smallpox and Biological Warfare". BBC.

- ^ "Tribes - Native Voices". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ a b Ranlet, P (2000). "The British, the Indians, and smallpox: what actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?". Pennsylvania History. 67 (3): 427–441. PMID 17216901.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- ^ King, J. C. H. (2016). Blood and Land: The Story of Native North America. Penguin UK. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84614-808-8.

- ^ Barras, V.; Greub, G. (June 2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism" (PDF). Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 497–502. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

However, in the light of contemporary knowledge, it remains doubtful whether his hopes were fulfilled, given the fact that the transmission of smallpox through this kind of vector is much less efficient than respiratory transmission, and that Native Americans had been in contact with smallpox >200 years before Ecuyer's trickery, notably during Pizarro's conquest of South America in the 16th century. As a whole, the analysis of the various 'pre-micro-biological' attempts at BW illustrate the difficulty of differentiating attempted biological attack from naturally occurring epidemics.

- ^ Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Government Printing Office. 2007. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-16-087238-9.

In retrospect, it is difficult to evaluate the tactical success of Captain Ecuyer's biological attack because smallpox may have been transmitted after other contacts with colonists, as had previously happened in New England and the South. Although scabs from smallpox patients are thought to be of low infectivity as a result of binding of the virus in fibrin metric, and transmission by fomites has been considered inefficient compared with respiratory droplet transmission.

- ^ Burke, James P. (May 2009). Pioneers of Second Fork. AuthorHouse. pp. 19–22. ISBN 978-1-4685-3459-7.

- ^ E. Wagner Stearn, and Allen E. Stearn, "Smallpox Immunization of the Amerindian." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 13.5 (1943): 601-613.

- ^ Donald R. Hopkins, The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History (U of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 271.

- ^ Paul Kelton, "Avoiding the Smallpox Spirits: Colonial Epidemics and Southeastern Indian Survival," Ethnohistory 51:1 (winter 2004) pp. 45-71.

- ^ Kristine B. Patterson, and Thomas Runge, "Smallpox and the native American." American journal of the medical sciences 323.4 (2002): 216-222. online

- ^ Dollar, Clyde D. (1977). "The High Plains Smallpox Epidemic of 1837-38". The Western Historical Quarterly. 8 (1): 15–38. doi:10.2307/967216. JSTOR 967216. PMID 11633561.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Fenn, Encounters at the Heart of the World: A History of the Mandan People (2015) ch. 14.

- ^ a b Marshall, Joseph (2005) [2004]. The Journey of Crazy Horse, A Lakota History. Penguin Books.

- ^ Lange, Greg. "Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Ostroff, Joshua (August 2017). "How a smallpox epidemic forged modern British Columbia". Maclean's. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Boyd, Robert; Boyd, Robert Thomas (1999). "A final disaster: the 1862 smallpox epidemic in coastal British Columbia". The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774–1874. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 172–201. ISBN 978-0-295-97837-6. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Swanky, Tom (2013). The True Story of Canada's "War" of Extermination on the Pacific – Plus the Tsilhqot'in and other First Nations Resistance. Dragon Heart Enterprises. pp. 617–619. ISBN 978-1-105-71164-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark M.; Lewis, Simon L. (2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- ^ Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo; et al. (2004). "When half of the population died: the epidemic of hemorrhagic fevers of 1576 in Mexico". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 240 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2004.09.011. PMC 7110390. PMID 15500972.

- ^ Acuna-Soto, R.; Stahle, D. W.; Cleaveland, M. K.; Therrell, M. D (April 2002). "Megadrought and megadeath in 16th century Mexico". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 360–362. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010175. PMC 2730237. PMID 11971767.

- ^ Degroot, Dagomar (2019). "Did Colonialism Cause Global Cooling? Revisiting an Old Controversy". Historical Climatology.

- ^ Denevan, William M. (1992). "The pristine myth: the landscape of the Americas in 1492". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01965.x. JSTOR 2563351.

- ^ Bruce Trigger. Natives and Newcomers: Canada's "Heroic Age" Reconsidered. (Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1985), 588–589.

- ^ Lange, Greg. (2003-01-23) Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s Archived 2008-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Historyink.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-06.

- ^ Smallpox, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Houston CS, Houston S (2000). "The first smallpox epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the fur-traders' words". Can J Infect Dis. 11 (2): 112–5. doi:10.1155/2000/782978. PMC 2094753. PMID 18159275.

- ^ Pearson, J. Diane (2003). "Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832". Wíčazo Ša Review. 18 (2): 9–35. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0017. S2CID 154875430. Project MUSE 46131.

- ^ The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; Pgs. 13-20, 73-94, 97

- ^ David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- ^ Lippi, Donatella; Gotuzzo, Eduardo; Caini, Saverio (August 2016). "Cholera". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (4). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PoH-0012-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27726771. S2CID 215231458.

- ^ a b "Cholera". HISTORY. 2023-03-27. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Merrell, D. Scott; Butler, Susan M.; Qadri, Firdausi; Dolganov, Nadia A.; Alam, Ahsfaqul; Cohen, Mitchell B.; Calderwood, Stephen B.; Schoolnik, Gary K.; Camilli, Andrew (June 2002). "Host-induced epidemic spread of the cholera bacterium". Nature. 417 (6889): 642–645. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..642M. doi:10.1038/nature00778. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 2776822. PMID 12050664.

- ^ "Cholera in Victorian London | Science Museum". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Fournier, Jean-Michel; Quilici, Marie-Laure (April 2007). "[Cholera]". Presse Médicale. 36 (4 Pt 2): 727–739. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2006.11.029. ISSN 0755-4982. PMID 17336031.

- ^ "General Information | Cholera | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-08-07. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Balasooriya, B. M. J. Kalpana; Rajapakse, Jay; Gallage, Chaminda (2023-12-10). "A review of drinking water quality issues in remote and indigenous communities in rich nations with special emphasis on Australia". Science of the Total Environment. 903: 166559. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.90366559B. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166559. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 37633366.

- ^ Fredrick, Tony; Ponnaiah, Manickam; Murhekar, Manoj V.; Jayaraman, Yuvaraj; David, Joseph K.; Vadivoo, Selvaraj; Joshua, Vasna (March 2015). "Cholera Outbreak Linked with Lack of Safe Water Supply Following a Tropical Cyclone in Pondicherry, India, 2012". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 33 (1): 31–38. ISSN 1606-0997. PMC 4438646. PMID 25995719.

- ^ "CHOLERA EPIDEMIC OF 1832 | Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University". case.edu. 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ "NYCdata | Disasters". www.baruch.cuny.edu. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Morgan, James P. (1988). "The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 260 (2): 272. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410020138049. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Powers, Ramon; Leiker, James N. (1998). "Cholera among the Plains Indians: Perceptions, Causes, Consequences". The Western Historical Quarterly. 29 (3): 317–340. doi:10.2307/970577. ISSN 0043-3810. JSTOR 970577.

- ^ Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now". Case Studies in Public Health: 77–99. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00017-2. ISBN 978-0-12-804571-8. PMC 7150208.

- ^ Lively, Cathy Purvis (2021-03-08). "COVID-19 in the Navajo Nation Without Access to Running Water : The lasting effects of Settler Colonialism". Voices in Bioethics. 7. doi:10.7916/vib.v7i.7889. ISSN 2691-4875.

- ^ a b c d e "Trail of Tears: Definition, Date & Cherokee Nation". HISTORY. 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b c "Western Adventurers and Male Nurses: Indians, Cholera, and Masculinity in Overland Trail Narratives". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ "Cholera - Pandemic, Waterborne, 19th Century | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Dean, Michael Emmans (May 2016). "Selective suppression by the medical establishment of unwelcome research findings: the cholera treatment evaluation by the General Board of Health, London 1854". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 109 (5): 200–205. doi:10.1177/0141076816645057. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 4872209. PMID 27150713.

- ^ Watrous, Mailing Address: PO Box 127; Us, NM 87753 Phone: 505 425-8025 Contact. "Pandemics - Fort Union National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cholera". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Lakhani, Nina (2021-04-28). "Tribes without clean water demand an end to decades of US government neglect". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ "Biography: Winona LaDuke". Biography: Winona LaDuke. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Watts, Sheldon (1999). Epidemics and History: Disease, Power and Imperialism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08087-2.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4006-3. OCLC 56632601.

- ^ Martin, Debra L; Goodman, Alan H (2002). "Health conditions before Columbus: paleopathology of native North Americans". Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.1.65. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071659. PMID 11788545.

- ^ Skinner, Nicole (20 August 2014). "Seals brought TB to Americas". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.15748. S2CID 183754215.