Night Mail

| Night Mail | |

|---|---|

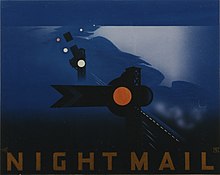

Film poster designed by Pat Keely | |

| Directed by | Harry Watt Basil Wright |

| Written by | W. H. Auden |

| Produced by | Harry Watt Basil Wright |

| Narrated by | Stuart Legg John Grierson |

| Edited by | Basil Wright |

| Music by | Benjamin Britten |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Associated British Film Distributors |

Release date |

|

Running time | 23 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £2,000 |

Night Mail is a 1936 British documentary film directed and produced by Harry Watt and Basil Wright, and produced by the General Post Office (GPO) Film Unit. The 24-minute film documents the nightly postal train operated by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) from London to Scotland and the staff who operate it. Narrated by John Grierson and Stuart Legg, the film ends with a "verse commentary"[1] written by W. H. Auden to a score composed by Benjamin Britten. The locomotive featured in the film is LMS Royal Scot Class 6115 Scots Guardsman.[2]

Night Mail premiered on 4 February 1936 at the Cambridge Arts Theatre in Cambridge, England in a launch programme for the venue. Its general release gained critical praise and became a classic of its own kind, much imitated by adverts and modern film shorts. Night Mail is widely considered a masterpiece of the British Documentary Film Movement.[3] A sequel was released in 1987, entitled Night Mail 2.

Synopsis

[edit]

The film follows the distribution of mail by train in the 1930s, focusing on the so-called Postal Special train, a train dedicated only to carrying the post and with no members of the public. The night train travels on the mainline route from Euston station in London to Glasgow, Scotland, on to Edinburgh and then Aberdeen. External shots include the train itself passing at speed down the tracks, aerial views of the countryside, and interior shots of the sorting van (actually shot in studio). Much of the film highlights the role of postal workers in the delivery of the mail.

Development

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1933, Stephen Tallents left his position as a secretary and director of the Empire Marketing Board (EMB), a government advertising agency that decided to cease operations, and began work as the first Controller of Public Relations for the General Post Office (GPO). In the wake of the EMB's demise, Tallents secured the transfer of the EMB Film Unit to the control of the GPO,[4] with EMB employee John Grierson transitioning from head of the EMB Film Unit to head of the newly formed GPO Film Unit, bringing most of its film staff with him.[3][5][6]

By 1936 the GPO was the nation's largest employer with 250,000 staff[7] and Tallents had begun to improve its public image, making the GPO spending more money on publicity than any other government entity at the time with a significant portion allocated to its film department.[8] Despite early GPO films primarily educating and promoting the public about its services, as with The Coming of the Dial (1933), they were also largely intended to ward off privatisation and promote a positive impression of the post office and its employees.[9]

Night Mail originated from the desire to produce a film that would serve as the public face of a modern, trustworthy postal system, in addition to boosting the low morale of postal workers at the time. The postal sector had seen an increase in profits in the late 1920s, but by 1936 wages had fallen 3% for the mostly working class GPO employees. The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927 had seriously curtailed postal union power, and the Great Depression fostered a general mood of pessimism. The liberal-minded Watt, Wright, Grierson, and other GPO film unit members, therefore, wanted Night Mail to focus not only on the efficiency of the postal system but its reliance on its honest and industrious employees.[9][10]

Pre-production

[edit]In 1935, directors Harry Watt and Basil Wright were called into Grierson's office who informed them of the GPO's decision to make a documentary film about the postal train that travels overnight from London Euston to Glasgow, operated by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS).[11] Watt had no knowledge of the service, and claimed the idea was originally instigated by Wright.[12] Wright prepared a rough shooting outline and script by travelling on the railway and used conversations picked up by a stenographer to write the dialogue, all of which was used in the film.[13] Watt then used the rough version to write a full script as the outline had lacked enough detail, "but there was a shape".[12] He contacted the LMS and was amazed to find the railway had its own film director who offered assistance. Watt described the research process as "reasonably straightforward", which included multiple trips along the railway, and soon completed a full treatment.[14] Wright later said that Watt changed his dialogue towards "a more human and down-to-earth" style which he praised him for doing.[13]

Early into development, however, Wright had to dedicate more time to other projects and left Watt in charge as director, yet both are credited as the film's two writers, directors, and producers.[5][12] Initially, Grierson sent his team to observe the postal train staff at work with the aim of producing an information film on the train's operations, but little of the information reported back was used. Its synopsis then developed into a more ambitious one, taking "considerable licence with the truth to portray a picture of the 'reality' of working life".[10]

The script developed, a film crew was assembled that included Wright, Watt, and cameramen Pat Jackson, Jonah Jones, and Henry "Chick" Fowle.[15][13] Brazilian-born Alberto Cavalcanti became involved as sound director who mixed the sound, dialogue, and music. Soon after, Grierson hired poet W. H. Auden for six months to gain film experience at the GPO and assigned him as Watt's assistant director with "starvation wages" of £3 a week, less than what Auden had earned as a school teacher. Auden made ends meet by living with Wright before moving in with fellow GPO employee, painter and teacher William Coldstream.[5] Watt cared little for Auden's fame and well known work, calling him "a half-witted Swedish deckhand" and complained of his frequent lateness during filming.[5] Watt later wrote: "[Auden] was to prove how wrong my estimation of him was, and leave me with a lifetime's awe of his talent".[16] The GPO secured a £2,000 budget for the film's production,[9] and calculated staff travel allowances by the accounts department totalling the salaries of the crew involved and setting aside money based on the figure.[17]

Production

[edit]Filming

[edit]

Production lasted for four months.[18] Due to technological constraints, the majority of Night Mail was shot as a silent film with the sound, dialogue, and music added in post-production. Jackson recalled there was not "a great deal" of synchronised sound filming while on location, barring some "fragments".[19] The on screen individuals were real life postal employees, but their dialogue was originally written by Watt and Wright who gained inspiration from the conversations they overheard while observing them at work.[9] The film was shot on standard 35 mm film using 61-metre (200 ft) long magazines with each canister allowing for around two minutes of footage. Footage captured on location were taken on portable Newman-Sinclair cameras, which were often too heavy for the cameraman to hold. For this reason, Watt estimated 90% of the film was shot on a tripod.[20]

The background sound was recorded in various locations, with the crew using the studio's sound van. This included recording at Bletchley station, where the crew recorded passing trains and instructed drivers to pass the station at speed while blowing the whistle so they could get a sound that gradually fades.[21] Shots of the train travelling at sunset were also taken at Bletchley, including a day where the team had spent the entire day at the studio before "we'd pile into a clapped-out car" and drive there to get the one shot.[22]

The platelayers were filmed several miles north of Hemel Hempstead as the film crew walked along the track to obtain shots of any railway action, including passing trains and the movement of signals and points.[15] They were joined by a "ganger", an employee of the LMS who alerted the team of oncoming trains and guided them to the sidewalk. Jackson recalled the yelling of "Up fast, stand clear" or "Down fast, stand clear" from the ganger at "infuriating regularity".[15] The crew came into contact with the platelayers, catching them at work and stopping for an oncoming train which included them sharing cigarettes and beer. Jackson noted down the various comments spoken amongst them for the voice recording during post-production and recalled the team's satisfaction upon viewing the footage the following morning.[15] Watt instructed Jackson to produce a rough assembly of the shot, his first experience at cutting film. However, problems arose due to errors in cutting which necessitated the crew's return to the location to reshoot the sequence. Jackson wrote: "We were lucky to find the same gang two miles further down the line".[23]

Filming at Crewe station for the train's 13-minute stop took several days, and involved the team setting up their own scaffolding and arc lamps and electrician Frank Brice running power cables onto the track to supply power from their generator.[24] Once finished, the equipment was packed in time for arrival of the postal train bound for London. Jackson boarded this train with the film reels for processing at Humphries Laboratories, sleeping on mail bags and arriving at the lab during the night. With the processed film ready in the morning, Jackson would take a postal train back to Crewe where the team could view the footage at a local cinema before it opened at 2:00 pm. Having viewed the footage, they would return to the station and set up the equipment to capture the next 13-minute stop.[25] Their time at Crewe was memorable for Auden, who claimed that when a shot of a guard was complete, "he dropped dead about thirty seconds later".[13]

Wright was responsible for the aerial shots of the train from a hired aircraft, while Watt filmed the interior and location shots.[5][10] The men in the sorting coach were real Post Office workers, but filmed in a reconstructed set built at the GPO's studio in Blackheath. They were instructed to sway from side to side to recreate the motion of the moving train which was accomplished by following the movement of a suspended piece of string.[5] Early attempts to simulate motion was done by shaking the set, but Watt wrote: "It just rattled like a sideboard in a junction town". Attempts to film while shaking the camera also failed as it merely produced a wobbly shot.[26]

Among Auden's first tasks as assistant director was taking charge of the second camera unit as they shot mail bags being transported at London's Broad Street station,[5] where a replica postal train was assembled for a night so the crew could film and record sound to match the footage they had captured at Crewe. Wright later thought it was "one of the most beautifully organised shots" of the entire film.[5] The filming session began at 5:00 pm and lasted for 14 hours without a break.[27] It included filming of the wheeltapper, who became the subject of an inside joke at the film studio when the crew forgot to shoot his scenes until the next morning. They adopted the term when the unit had missed a shot.[27] Shots taken at Broad Street were incorporated into the Crewe sequence in the film.[28]

Fowle is credited with capturing several dramatic shots, including the mail bag being dropped off into a trackside net at high speed. To do this, he leaned out of the coach where the metal arm reached outward while his two colleagues held onto his legs, and got the shot just before the arm quickly swung back upon contact.[5] Lighting was limited for this sequence as the crew could only work with small battery-powered lights.[22] Fowle also solved the problem of recording the sound of the train as it travelled along the track and points, which produced unsatisfactory results when a microphone was placed on a real train. The crew had even placed their sound van onto a bogie coupled behind a train and travelled up and down a stretch of line for an entire day, but the overall sound drowned it out.[21] Jackson, whose brother was a model railway enthusiast, then suggested recording using a model train, and a class-six engine and track was obtained from model manufacturer Basset-Lowke with that were set up in the film studio. Jackson proceeded to push the engine back and forth along the track at the same speed as the train in the picture which produced the sound they needed.[29] Watt realised the importance of getting the sound right: "Without that sound, the centre of a film that was to make my career would have completely failed".[30]

During the construction of the sorting coach set, Watt, Jones, and Jackson were assigned an engine to themselves and travelled up and down Beattock Summit in Scotland several times. This included another dangerous shot captured by Jackson, after attempts to take footage of the driver's cab produced film that was too dark. To solve this, Jackson sat atop of the coal pile in the locomotive's tender while holding a reflective sheet made with silver paper that acted as a mirror to make subjects brighter. As he filmed, the train passed a bridge which knocked the reflector off and narrowly missed his head.[5] The cameramen continued into Scotland to film the closing shots at dawn, and Watt captured the partridges, rabbits, and dogs at a Dumfries farm.[31] During their stay in Glasgow, Grierson informed Watt that upon completing the interior scenes and recording the sound, the film's budget had been spent and suggested that filming cease. Watt still had more footage to capture, however, wishing for a coda that showed an engine being cleaned and serviced at the end of the journey before starting its next one.[17] The situation was solved when the three stayed with Watt's mother in Edinburgh and travelled to Glasgow in the guard's van to get the final shots.[17]

Poem sequence

[edit]After viewing a rough assembly of the film, Grierson, Wright, and Cavalcanti agreed that a new ending was needed.[5] Wright recalled that it was most likely Grierson who noted that up to this point, the film had documented the "machinery" of delivering letters, but "What about the people who write them and the people who get them?"[5] Grierson, influenced by Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein's use of montage and poetry in Old and New (1929) and Sentimental Romance (1930),[32] thought a sequence with a spoken poem set to music would was deemed more suitable, and Auden was set the task of writing a "verse commentary". Watt expressed his disagreement with the idea at first, but came round to it when it presented the opportunity in shooting additional footage and using previously shot film that was could not be used to complete the sequence.[5] The sequence includes "at least two shots" that Wright had filmed for a test shoot for a film that was never made.[33] Auden and Watt went through many drafts of the verse to exactly match the rhythm of the travelling train.[34]

Auden's poem for the sequence, entitled "Night Mail", was written at the film unit's main office in Soho Square.[5] Watt described his work area as "A bare table at the end of a dark, smelly, noisy corridor", a contrast to the more peaceful surroundings that he was used to working in.[35] He paced it to match the rhythm of the train's wheels "with a stopwatch in order to fit it exactly to the shot".[5] Grierson biographer Forsyth Hardy wrote that Auden wrote the verse on a trial and error basis, and was cut to fit the visuals by editor Richard McNaughton in collaboration with Cavalcanti and Wright. Many lines from the original version were discarded and became "crumpled fragments in the wastepaper basket",[36] including one that described the Cheviot Hills by the English–Scottish border as "uplands heaped like slaughtered horses" that Wright considered too strong for the landscape that was shot for it.[5] Wright's original idea was to start the sequence with shots of a train ascending Beattock Summit accompanied by a voice saying "I think I can, I think I can."[37]

The sequence begins slowly before picking up speed, so that by the penultimate verse, assistant and narrator Stuart Legg speaks at a breathless pace, which involved several pauses in recording so he could catch his breath.[38] Before recording his parts, Legg took a deep breath and recited the poem until he could no longer breathe, and ended with a "Huh" sound of taking a breath. The "Huh" sound was located and marked down on the audio tape to show where he was to continue.[39] As the train slows toward its destination, the final verse, which is more sedate, is read by Grierson.[36][40] Hardy added that what was retained made Night Mail "as much a film about loneliness and companionship as about the collection and delivery of letters", which made the film "a work of art".[36]

Around the time of Auden's arrival at the GPO, Cavalcanti suggested to Grierson that he hire 22-year-old English composer Benjamin Britten to contribute music to the film department, including the musical score for Night Mail. Grierson accepted, assigning Britten a weekly salary of £5.[5][41] Watt urged Britten to avoid "any bloody highbrow stuff", and showed him the picture while playing an American jazz record and requested "this kind of music".[19] Britten had little interest in jazz music, but was given artistic freedom to compose.[5] He was allowed an orchestra of ten musicians, and used a compressed air cylinder and sandpaper to create a "sound picture" of the pistons and pumps of a steam locomotive at speed. The music was recorded at the Blackheath studio,[42] Jackson claimed Britten had only used five musicians, all of whom were hand picked.[43] In order to keep the orchestra in time, Britten conducted to an "improvised visual metronome" that involved marks cut at particular intervals in the film that appeared as flashes on the screen.[42] By 12 January 1936, the music had been written which was followed by the recording sessions that began on 15 January.[44]

Narration

[edit]After the poem sequence was finalised, the remaining sound recording which included the narrative commentary.[clarification needed] Wright thought Jackson's voice was suitable for the part and suggested it to him. Jackson agreed, but disliked the sound of his voice upon playback: "My dulcet tones are immortalised in a few simple statements [...] I sounded like some Oxford pimp on the prowl, and never having been to Oxford, I should know".[43]

Release

[edit]

The film premiered on 4 February 1936 at the Cambridge Arts Theatre in Cambridge[5][11][45] as one of the films presented at the launch screening at the venue.[18] A screening was held the following morning.[46] Jackson, Watt, and Wright were among the GPO staff present; the former recalled the audience's enthusiastic response to the film which included an "enormous applause" at the end.[29] The film was the GPO's only production to be released commercially in 1936.[47]

Wright was angered upon its general release as he found out that he was jointly credit as producer and director with Watt, when he believed he had done most of the work.[5] Watt was shocked to find that he was credited as a producer, as he argued he had only directed the film. He tried to have the on-screen credits changed so his name separated from Wright's, "in letters as tiny as Grierson cared", but the latter refused and despite convincing Watt to leave the credits unaltered, Watt never forgave Grierson.[48] Cavalcanti noted that he was credited for "'sound direction', which didn't even exist as a credit", but Grierson claimed that Cavalcanti had asked for his name to be excluded from the GPO's credits in case his involvement in such a documentary unit undermined his reputation in commercial cinema.[49]

Night Mail was promoted with a largely successful advertising campaign to aid its release. The GPO commissioned posters, special screenings, and other soft publicity opportunities, taking advantage of the glamorous image and popularity of railway films to promote Night Mail. Unlike other GPO films, which were primarily screened in schools, professional societies, and other small venues, Night Mail was shown in commercial cinemas as an opening for the main feature. However, poor contracts for short documentary films meant Night Mail failed to make a significant profit despite its high viewership.[9] In 1938, the film was re-released as part of the 100th anniversary of the travelling post office, which featured a collector's edition information booklet on the film.[50] The first broadcast on BBC Television was not until 16 October 1949.[51]

An early screening in the U.S., at New York's Museum of Modern Art, was for its "The Documentary Film" series, lasting from January through May 1946. This film was shown on January 28, 29, 30, and 31.[52]

In 2007, Night Mail was released on DVD by the British Film Institute following a digital restoration of the original negatives. The set includes 96 minutes of bonus features, including the 1986 sequel Night Mail 2.[5]

Reception

[edit]Writing for The Spectator in 1936, Graham Greene gave the film mild praise, describing the "simple visual verses of Mr Auden [as] extraordinarily exciting", while admitting that the film as a whole "isn't a complete success". Greene dismissed the criticism of including Auden's verse from C. A. Lejeune's review in The Observer, however he found fault with some of the quality and clarity of some of the scenes.[53] The Times praised the film for showing "the marvellous exactitude with which his Majesty's mails are distributed and delivered."[54] A review in The Daily Worker noted "the cool, competent way in which the men go about their job awakens pride and admiration in those who appreciate the dignity of labour."[54] In The Morning Post, a reviewer believed that Night Mail's achievement was obtaining "natural acting from the railway and postal officials concerned, as it is extremely difficult to prevent people from 'putting on their best behaviour' when they know they are about to be photographed".[54]

Film critic Caroline Lejeune wrote a more critical review in The Observer, noting that she had "minor cavils" against the film for the use of accents and for "versifying" the final sequence. However, she noted that it makes a "very convincing adventure of something that happens every week of our lives" and "is more exciting than any confected drama".[55] Tallents praised Night Mail highly, as it "Had no snob appeal, making falsely glamorous and desirable to humble people the fundamentally commonplace and vulgar luxuries of the rich. It took as its raw material the everyday life of ordinary men and from that neglected vein won interest, dignity and beauty [...] and struck a more universal note."[56]

Analysis

[edit]According to documentary author Betsy McLane, Night Mail makes three primary arguments: First, the postal system is complex and must function under the auspices of a national government in order to thrive. Second, the postal system is a model of modern efficiency, and third, postal employees are industrious, jovial, and professional. Grierson also articulated a desire to reflect "Scottish expression" and unity between England and Scotland (two years after the formation of the Scottish National Party, and growing calls for Scottish home rule) with Night Mail.[57] More broadly, British Film Institute historian Ian Aitken describes Grierson's position on the function of documentary film as "representing the inter-dependence and evolution of social relations in a dramatic and symbolic way".[58] He cites Night Mail’s portrayal of the postal system's practical and symbolic importance through both humanistic realism and metaphorical imagery as characteristic of Grierson's ideals.

Author A. R. Fulton points out effective film editing to build suspense on everyday operations, such as the mail bags being caught by the track side nets. The scene is "humanized" with the new starter learning the task and lasts no longer than 90 seconds, yet it comprises 58 shots, averaging under two seconds per shot. Fulton compared its construction to that of Battleship Potemkin (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein.[59] Fulton believes the main theme of Night Mail is suggested by one of Auden's lines in the poem: "All Scotland waits for her".[60]

The film utilises three contrasting techniques to convey its meaning. First, Night Mail portrays the daily activities of the postal staff on a human scale, with colloquial speech and naturalistic vignettes, like sipping beer and sharing inside jokes. This was the approach favoured by Watt, who apprenticed under ethnographic filmmaker Robert Flaherty. Second, Night Mail uses expressionistic techniques like heavy back lighting and the lyric poetry of Auden to convey the grand scale of the postal endeavour. These techniques were championed by Wright, a lover of experimental European cinema. Finally, the film occasionally employs narration to explain the particular marvels of the mail system. This factual exposition was promoted by Grierson.[9]

Night Mail, though edited in a naturalistic style, nevertheless utilises potent lyric symbolism. The film contrasts the national importance of the postal system, embodied by a train journey which literally enables cross-country communication, with the local accents and colloquial behaviour of its staff, demonstrating that a great nation is composed of its humble and essential regions and peoples. Night Mail further reinforces the strength of national unity by juxtaposing images of cities and countryside, factories and farms. The technologically advanced rail system, nestled comfortably in the immutable landscape, demonstrates that modernity can be British.[61]

The main body of the film uses minimal narration, usually in the present tense and always underscored with diegetic sound. This ancillary commentary serves to elaborate on the onscreen action (“The pouches are fixed to the standard by a spring clip”) or invigorate and expand the world of the film (“Four million miles every year. Five hundred million letters every year.”) The bulk of the story is conveyed through dialogue and imagery, however, leaving the narrative thrust in the hands of the postal workers.[62]

Night Mail’s significance is due to a combination of its aesthetic, commercial, and nostalgic success. In contrast to previous GPO releases, Night Mail garnered critical notice and commercial distribution through Associated British Film Distributors (ABFD).[58] Night Mail was also one of the first GPO films built on a narrative structure, a critically influential technique in the development of documentary filmmaking.[3]

More broadly, the personnel of the GPO and Night Mail contributed to the development of documentary film worldwide. Grierson, in particular, pioneered not only a highly influential theory of "actuality" film, but developed structures of funding, production, and distribution which persist to this day. He advocated state support for documentary film as well as arguing the civic merits of educational film. Night Mail, one of the first commercial successes of the GPO, served as a "proof of concept" that his methods and goals could be publicly successful. The film's blend of social purpose and aesthetic form position it as an archetypal film of the British Documentary Film Movement. For these reasons, the film is a staple of film education worldwide.[63]

English television producer and author Denys Blakeway praised Auden's contributions and the coda sequence which "rescued the documentary from plodding Post Office propaganda and helped to establish the emerging form as a new branch of the arts".[11]

Legacy and adaptations

[edit]Despite its many critical successes, the GPO Film Unit was ultimately doomed by its limited budget and by unfavourable terms for short documentary films under the 1927 Cinematograph Films Act, which required British cinemas to present a minimum quota of British feature films. The unit's films could not compete with commercial fare and the Treasury's sceptical assessment of its value. The unit disbanded in 1940 and reformed as the Crown Film Unit under the Ministry of Information.[8]

Grierson and many other prominent members of the GPO Film Unit continued their work in documentary film in the United Kingdom and abroad. Grierson has subsequently been called "the person most responsible for the documentary film as English speakers have known it".[64] Night Mail itself is sometimes considered the apotheosis of the collaborative work of the GPO Film Unit,[34] a beloved, and nearly unique ode to the Royal Mail, the British people, and the creative possibilities of "actuality" films.

The film was widely admired by contemporary critics as well as current scholars, and remains popular with the British public. School children often memorise "Night Mail", and the film has been parodied in advertisements and sketch shows.[9]

In 2000, Night Mail was named Best Railway Film of the Century at the Festival International du Film Ferroviaire.[65]

In 2002, poet and playwright Tony Harrison was commissioned to "recast" Night Mail for an episode of The South Bank Show. The piece, entitled Crossings, was described by author Scott Anthony as "considerably less believable" than the original Night Mail and comes across as "a cuttings job."[66]

1986 sequel poem

[edit]In 1986, fifty years after the release of the original film, English poet Blake Morrison was hired to write a poem for a sequel, Night Mail 2, which tells the story of the contemporary mail delivery system. Morrison incorporated the line "uplands heaped like slaughtered horses" into his poem which was originally cut from Auden's version. He concluded: "For that alone, I was pleased to be part of the remake".[5]

1988 British Rail advert

[edit]In 1988, British Rail produced the "Britain's Railway" television advert which showed the business sectors introduced in 1986. This used the first stanza of Auden's poem, followed by some new lines:[67]

Passing the shunter intent on its toil, moving the coke and the coal and the oil. Girders for bridges, plastic for fridges. Bricks for the site are required by tonight. Grimy and grey is the engine's reflection, down to the docks for the metal collection.

Passenger trains full of commuters, bound for the office to work in computers. The teacher, the doctor, the actor in farce; the typist, the banker, the judge in first class. Reading the Times with the crossword to do, returning at night on the six forty-two.

In other media

[edit]The first concert performance of Britten's score took place on 7 November 1997 at the Conway Hall in London. The score was first published in 2002. It imagines the real sounds of the train and incorporates these imaginary sounds into the score.[68] At over fifteen minutes, it is one of Britten's most elaborate film scores.[69]

Night Mail was the basis for a song of the same name by British band Public Service Broadcasting for their 2013 album Inform-Educate-Entertain.

On 14 May 2014, the film was one of those chosen for commemoration in a set of Royal Mail stamps depicting notable GPO Film Unit films.[70]

The opening stanza of the poem was sampled heavily by electronic musician Aphex Twin, under his AFX moniker, in the song Nightmail 1, officially released by Warp in July 2017 as part of the orphans digital EP.[71]

The copyright on the film expired after 50 years.

References

[edit]- ^ "Verse commentary by W. H. Auden" is the standard phrase used by distributors of the film and by film historians; e.g. [1]

- ^ "Flying Scotsman Announcement", Flying Scotsman Announcement, National Railway Museum, 16 March 2012, archived from the original on 3 March 2013, retrieved 25 February 2013

- ^ a b c McLane, Betsy (2012). A new history of documentary film. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 73–92. ISBN 9780826417510.

- ^ Anthony, Scott; Mansell, James (2011). The projection of Britain: A history of the GPO film unit. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781844573745.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Morrison, Blake (1 December 2007). "Stamp of excellence". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Night Mail (1936)", Night Mail, BFI Screenonline, retrieved 25 February 2013

- ^ Blakeway 2010, p. 67.

- ^ a b Swann 1989.

- ^ a b c d e f g Anthony 2007.

- ^ a b c Blakeway 2010, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Blakeway 2010, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Sussex 1975, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Sussex 1975, p. 67.

- ^ Watt 1974, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c d Jackson 1999, p. 25.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Watt 1974, p. 88.

- ^ a b Sussex 1975, p. 75.

- ^ a b Sussex 1975, p. 72.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 82.

- ^ a b Watt 1974, p. 90.

- ^ a b Sussex 1975, p. 68.

- ^ Jackson 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Jackson 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Sussex 1975, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 89.

- ^ a b Watt 1974, p. 86.

- ^ Sussex 1975, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Barr, Charles (11 July 2011). "Pat Jackson: Director who learnt his trade on 'Night Mail' and went on to make one of the finest wartime films". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 91.

- ^ Watt 1974, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Sussex 1975, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Sussex 1975, pp. 65–78.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Hardy 1979, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Blakeway 2010, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Sussex 1975, p. 73.

- ^ Watt 1974, p. 93.

- ^ Blakeway 2010, p. 68.

- ^ a b Blakeway 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b Jackson 1999, p. 31.

- ^ Mitchell 1981, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Christiansen 1996, p. 101.

- ^ Jackson 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Swann 1989, p. 71.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Mitchell, Alastair and Poulton, Alan: A Chronicle of First Broadcast Performances of Musical Works in the United Kingdom, 1923-1996 (2019), p. vii

- ^ Barry, Iris. "The Documentary Film, Prospect and Retrospect." The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 13:2 (December 1945), 10.

- ^ Greene, Graham (20 March 1936). "The Milky Way/Strike Me Pink/Night Mail/Crime and Punishment". The Spectator. (reprinted in: Taylor, John Russell, ed. (1980). The Pleasure Dome. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0192812866.)

- ^ a b c Anthony 2007, p. 81.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Hardy, Forsyth (1966). Grierson on documentary. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-0571143818.

- ^ a b Aitken, Ian (1990). Film and reform. London: Routledge.

- ^ Fulton 1960, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Fulton 1960, p. 189.

- ^ Aitken, Ian (1998). The documentary film movement. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Guynn, William (1990). A cinema of nonfiction. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 163–176.

- ^ Druick, Zoe; Williams, Deane (2014). The Grierson effect. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Ellis, Jack (2000). John Grierson: Life, contributions, influence. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 363.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 71.

- ^ John Chenery http://www.lightstraw.co.uk/gpo/film/nightmail1.html

- ^ Mitchell, Donald. Britten and Auden in the thirties: the year 1936: the TS Eliot memorial lectures delivered at the University of Kent at Canterbury in November 1979. Faber & Faber, 1981. p. 83

- ^ Mitchell, Donald. Britten and Auden in the thirties: the year 1936: the TS Eliot memorial lectures delivered at the University of Kent at Canterbury in November 1979. Faber & Faber, 1981. p. 89

- ^ Lee, Julia (13 May 2014). "Great British Film — Projecting the best of British film-making". Stamp Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "orphans". Warp. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

Sources

- Anthony, Scott (2007). Night Mail (BFI Film Classics). BFI Publishing. ISBN 978-1-844-57229-8.

- Blakeway, Denys (2010). The Last Dance: 1936, The Year Our Lives Changed. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-848-54389-8.

- Christiansen, Rupert (1996). Cambridge Arts Theatre: Celebrating Sixty Years. Granta. ISBN 978-1-857-57052-6.

- Fulton, Albert Rondthaler (1960). Motion Pictures: The Development of an Art from Silent Films to the Age of Television. University of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 60013471.

- Hardy, Forsyth (1979). John Grierson: A Documentary Biography. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10331-6.

- Jackson, Pat (1999). A Retake Please!: Night Mail to Western Approaches. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-853-23953-6.

- Mitchell, Donald (1981). Britten and Auden in the Thirties: The Year 1936. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95814-9.

- Sussex, Elizabeth (1975). The Rise and Fall of British Documentary: The Story of the Film Movement Founded by John Grierson. 978-0-520-02869-2.

- Swann, Paul (1989). The British Documentary Film Movement, 1926–1946. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33479-2.

- Watt, Harry (1974). Don't Look at the Camera. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-236-17717-2.

External links

[edit]- Night Mail at IMDb

- Night Mail is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- 1936 films

- British documentary films

- Documentary films about rail transport

- British black-and-white films

- London, Midland and Scottish Railway

- Films directed by Harry Watt

- Films directed by Basil Wright

- 1936 documentary films

- Black-and-white documentary films

- 1936 in the United Kingdom

- Documentary films about the United Kingdom

- GPO Film Unit films

- Postal history of the United Kingdom

- Films set in England

- Films set in Scotland

- Films about postal systems

- Films shot in Greater Manchester

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s British films

- English-language documentary films

- Films scored by Benjamin Britten