Pamphylia

| Pamphylia (Παμφυλία) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

Ruins of the main street in Perga, capital of Pamphylia | |

| Location | Southern Anatolia |

| State existed: | - |

| Nation | Pamphylians, Pisidians, Greeks |

| Historical capitals | Perga, Attaleia |

| Roman province | Pamphylia |

| |

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

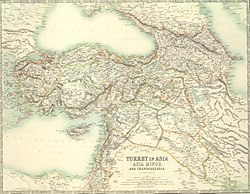

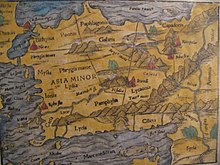

In ancient geography, Pamphylia (/pæmˈfɪliə/) was the region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the north by Pisidia and was therefore a country of small extent, having a coast-line of only about 120 km (75 miles) with a breadth of about 50 km (30 miles).[citation needed] Under the Roman administration the term Pamphylia was extended so as to include Pisidia and the whole tract up to the frontiers of Phrygia and Lycaonia, and in this wider sense it is employed by Ptolemy.

Name

The name Pamphylia comes from the Greek Παμφυλία,[1] itself from πάμφυλος (pamphylos), literally "of mingled tribes or races",[2] a compound of πᾶν (pan), neuter of πᾶς (pas) "all"[3] + φυλή (phylē), "race, tribe".[4] Herodotus derived its etymology from a Dorian tribe, the Pamphyloi (Πάμφυλοι), who were said to have colonized the region.[5] The tribe, in turn, was said to be named after Pamphylos (Greek: Πάμφυλος), son of Aigimios.[6][7]

Origins of the Pamphylians

The Pamphylians were a mixture of aboriginal inhabitants, immigrant Cilicians (Template:Lang-el) and Greeks[8] who migrated there from Arcadia and Peloponnese in the 12th century BC.[9] The significance of the Greek contribution to the origin of the Pamphylians can be attested alike by tradition and archaeology[10] and Pamphylia can be considered a Greek country from the early Iron Age until the early Middle Ages.[11] There can be little doubt that the Pamphylians and Pisidians were the same people, though the former had received colonies from Greece and other lands, and from this cause, combined with the greater fertility of their territory, had become more civilized than their neighbours in the interior.[citation needed] But the distinction between the two seems to have been established at an early period. Herodotus, who does not mention the Pisidians, enumerates the Pamphylians among the nations of Asia Minor, while Ephorus mentions them both, correctly including the one among the nations on the coast, the other among those of the interior.[citation needed]

A number of scholars have distinguished in the Pamphylian dialect important isoglosses with both Arcadian and Cypriot (Arcadocypriot Greek) which allow them to be studied together with the group of dialects sometimes referred to as Achaean since it was settled not only by Achaean tribes but also colonists from other Greek-speaking regions, Dorians and Aeolians.[12] The legend related by Herodotus and Strabo, which ascribed the origin of the Pamphylians to a colony led into their country by Amphilochus and Calchas after the Trojan War, is merely a characteristic myth.[citation needed]

History

The region of Pamphylia first enters history in Hittite documents.[citation needed] In a treaty between the Hittite Great King Tudhaliya IV and his vassal, the king of Tarhuntassa, we read of the city "Parha" (Perge), and the "Kastaraya River" (Classical Kestros River, Turkish Aksu Çayı).[citation needed]

The first historical mention of "Pamphylians" is among the group of nations subdued by the Mermnad kings of Lydia;[citation needed] they afterwards passed in succession under the dominion of the Persian and Hellenistic monarchs. After the defeat of Antiochus III in 190 BC they were included among the provinces annexed by the Romans to the dominions of Eumenes of Pergamum; but somewhat later they joined with the Pisidians and Cilicians in piratical ravages, and Side became the chief centre and slave mart of these freebooters. Pamphylia was for a short time included in the dominions of Amyntas, king of Galatia, but after his death lapsed into a district of a Roman province. The Pamphilians became largely hellenized in Roman times, and have left magnificent memorials of their civilization at Perga, Aspendos and Side.[citation needed]

As of 1911 the district was largely peopled with recent settlers from Greece, Crete and the Balkans, a situation which changed considerably as a result of the disruptions attendant on the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the war between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s.[citation needed]

List of Pamphylians

- Diodorus of Aspendos, Pythagorean philosopher (4th century BC)[13][14]

- Apollonius of Perga, astronomer, mathematician (c. 262 - c. 190 BC)

- Artemidorus of Perga, proxenos in Oropos (c. 240 -180 BC)[15]

- Aetos (son of Apollonius) from Aspendos, Ptolemaic commander, founder of Arsinoe (Cilicia) (c. 238 BC)[16]

- Mnaseas (son of Artemon) from Side, sculptor (end 3rd century BC)[17]

- Orestas (son of Erymneus) from Aspendos, proxenos in Dreros (Crete), (end 3rd - beginning 2nd century BC)[18]

- Thymilus of Aspendos, stadion (distance of 180–190 m) running race victor (winner) in Olympics 176 BC [19]

- Apollonios (son of Koiranos) from Aspendos, Ptolemaic commander, proxenos in Lappa and Aptera (Crete) (1st half - 2nd century BC)[20]

- Asclepiades (son of Myron) from Perga, physician honoured by the people of Seleucia (3rd - 2nd century BC)[21]

- Plancia Magna from Perga, influential citizen, benefactress, high-priestess of Artemis (1st and 2nd century AD)[22]

- Menodora (daughter of Megacles) from Sillyon, magistrate and benefactor (c. 2nd century AD)[23]

- Zenon (son of Theodorus) from Aspendos, architect of the Aspendos theatre (2nd century AD)[24]

- Apollonius of Aspendos (son of Apollonius), poet (2nd/early 3rd century AD)[25]

- Aurelia Paulina from Perga, prominent noblewoman of Syrian origin, donator, high-priestess of Artemis (2nd and 3rd century AD)

- Probus from Side, martyr (died c. 304 AD)

- Philip of Side, historian (c. 380 - after 431)

- Matrona of Perge, saint, abbess of Constantinople, (late 5th - early 6th century AD)[26]

- Antony I Kassymatas from Sillyon, patriarch of Constantinople (c. 780 - 837)

Archaeological sites

- Antalya

- Aspendos

- Etenna

- Eurymedon Bridge at Aspendos, a Roman bridge which was reconstructed by the Seljuks and follows a zigzag course over the river

- Eurymedon Bridge at Selge, a Roman bridge

- Perga

- Side

- Sillyon

Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of the Roman province of Pamphylia Prima (I) listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[27]

Ancient episcopal sees of the Roman province of Pamphylia Secunda (II) listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[27]

Ancient episcopal sees of the Roman province of Pamphylia Tertia (III) listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[27]

- Cotrada, ?Metropolitan? Archdiocese

- Leontopolis in Pamphylia (Ulupınar, Kemer)

See also

Notes

- ^ Παμφυλία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ πάμφυλος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ πᾶς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ φυλή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, 5.68

- ^ Πάμφυλος, William J. Slater, Lexicon to Pindar, on Perseus

- ^ George Grote : A History of Greece. p. 286; Irad Malkin : Myth and Territory in the Spartan Mediterranean. Cambridge U Pr, 2003. p. 41.

- ^ Pamphylia, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani, Jean-Pierre Mohen, J. L. Lorenzo, and V. M. Masson , History of Humanity-Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century B.C (Vol II), UNESCO, 1996, p.425

- ^ Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, The cities of the eastern Roman provinces, Clarendon Press, 1971, p.123

- ^ John D. Grainger, The cities of Pamphylia, Oxbow Books, 2009, p.27

- ^ A.-F. Christidis, A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p.427

- ^ "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, page 1015 (v. 1)". Ancientlibrary.com. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ Die Fragmente Der Griechischen Historiker, Continued - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ Epigr. tou Oropou 148

- ^ SEG 39:1426 - The Hellenistic Monarchies: Selected Papers Page 264 By Christian Habicht ISBN 0-472-11109-4

- ^ IK Side I 1

- ^ BCH 1936:280,1

- ^ "links to Greek and Latin Authors in the web". Attalus. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ SEG 23:573 R.S. Bagnall (1976) The Administration of the Ptolemaic Possessions outside Egypt, p. 124. Brill Archive.

- ^ Epigr.Anat. 11:104,5 Inscriptions for Physicians

- ^ Elaine Fantham, Helene Peet Foley, Natalie Boymel Kampen, Sarah B. Pomeroy & H. Alan Shapiro (1995) Women in the Classical World: Image and Text, Oxford University Press

- ^ Riet van Bremen: Women and Wealth Chapter 14, p. 223 in "Images of Women in Antiquity" Page 223 Editors Averil Cameron, Amélie Kuhrt ISBN 0-415-09095-4

- ^ "Aspendos Archaeological Project". Aspendosproject.com. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ IG VII 1773 - The Context of Ancient Drama Page 192 By Eric Csapo, William J. Slater ISBN 0-472-08275-2

- ^ "Internet Medieval Sourcebook". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ a b c Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819-1013

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Livius.org: Pamphylia

- Asia Minor Coins: Pamphylia ancient Greek and Roman coins from Pamphylia