Parthenopean Republic

Parthenopean Republic Repubblica Partenopea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1799–1799 | |||||||||

|

The flag of the Parthenopean Republic was the French tricolor with a yellow stripe in the place of the white one, similar to the flag of Chad or the flag of Romania. | |||||||||

The Kingdom of Naples briefly became a republic in 1799. | |||||||||

| Status | Client state of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Naples | ||||||||

| Common languages | Central Italian, Southern Italian | ||||||||

| Government | Presidential directorial Republic | ||||||||

| Director | |||||||||

• 1799 | Carlo Lauberg | ||||||||

• 1799 | Ignazio Ciaia | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars | ||||||||

• French invasion | 21 January 1799 | ||||||||

• Sicilian invasion | 13 June 1799 | ||||||||

| Currency | Napoletan tornese, Napoletan carlino | ||||||||

| |||||||||

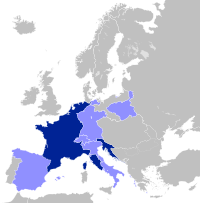

The Parthenopean Republic (Template:Lang-it) was a French First Republic-supported republic in the territory of the Kingdom of Naples, formed during the French Revolutionary Wars after King Ferdinand IV fled before advancing French troops. The republic existed from 21 January 1799[1] to 13 June 1799, when Ferdinand's kingdom was re-established.

Origins of the Republic

On the outbreak of the French Revolution King Ferdinand IV of Naples and Queen Maria Carolina did not at first actively oppose reform; but after the fall of the French monarchy they became violently opposed to it, and in 1793 joined the first coalition against France, instituting severe persecutions against all who were remotely suspected of French sympathies. Republicanism, however, gained ground, especially among the aristocracy.

In 1796 peace with France was concluded, but in 1798, during Napoleon's absence in Egypt and after Nelson's victory at the Battle of the Nile, Maria Carolina induced Ferdinand to go to war with France once more. Nelson himself arrived at Naples in September 1798, where he was enthusiastically received. The Neapolitan army had 70,000 men hastily summoned under the command of the Austrian general Karl von Mack: on 29 November it entered Rome,[2] which had been evacuated by the French, to restore Papal authority. However, after a sudden French counter-attack, his troops were forced to retreat and eventually routed. A contemporary satirist said of the king's conquest of Rome: "He came, he saw, he fled".[3]

The king hurried back to Naples. Although the lazzaroni (the lowest class of the people) were devoted to the Bourbon dynasty and ready to defend it, he embarked on Nelson's Vanguard and fled with his court to Palermo in a panic. The prince Francesco Pignatelli Strongoli took over the city and the fleet was burned.

The wildest confusion prevailed, and the lazzaroni massacred numbers of persons suspected of republican sympathies, while the nobility and the educated classes, finding themselves abandoned by their king, began to contemplate a republic under French auspices to avoid anarchy. On 12 January 1799, Pignatelli signed in Sparanise the surrender to the French general Championnet. Pignatelli also fled to Palermo on 16 January 1799.

When the news of the treaty with the French reached Naples and the provinces, the lazzaroni rebelled. Though ill-armed and ill-disciplined, they resisted the enemy with desperate courage. In the meantime the Jacobin and Republican parties of Naples surged, and civil war broke out. On 20 January 1799 the Republicans conquered the fortress of Castel Sant'Elmo, and the French were therefore able to enter the city. The casualties were 8,000 Neapolitans and 1,000 French.

The Republic

On 21 January 1799 the Parthenopean Republic was proclaimed. The name referred to an ancient Greek colony Parthenope on the site of the future city of Naples. The Republic had no real domestic constituency, and existed solely due to the power of the French Army. The Republic's leaders were men of culture, high character and birth, such as Gennaro Serra, Prince of Cassano Irpino but they were doctrinaire and impractical, and they knew very little of the lower classes of their own country. The new government soon found itself in financial difficulties, owing to Championnet's demands for money (he was later relieved for graft); it failed to organise an army (and was therefore dependent on French protection), and met with little success in its attempts to "democratise" the provinces.

Meanwhile, the court at Palermo sent Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo, a wealthy and influential prelate, to Calabria to organize a counter-revolution. He succeeded beyond expectation, and with his "Christian army of the Holy Faith" (Esercito Cristiano della Santa Fede). An English squadron approached Naples and occupied the island of Procida, but after a few engagements with the Republican fleet commanded by Francesco Caracciolo, an ex-officer in the Bourbon navy, it was recalled to Palermo, as the Franco–Spanish fleet was expected.

Ruffo, supported by the Russian and Turkish ships under command of Admiral Ushakov, now marched on the capital, whence the French, except for a small force under Méjean, withdrew. The scattered Republican detachments were defeated, only Naples and Pescara holding out.

On 13 June 1799 Ruffo and his troops reached Naples, and after a desperate battle at the Ponte della Maddalena, entered the city. For weeks the Calabresi and lazzaroni continued to pillage and massacre, and Ruffo was unable, even if willing, to restrain them. However, the Royalists were not masters of the city, for the French in Castel Sant'Elmo and the Republicans in Castel Nuovo and Castel dell'Ovo still held out and bombarded the streets, while the Franco–Spanish fleet might arrive at any moment. Consequently, Ruffo was desperately anxious to come to terms with the Republicans for the evacuation of the castles, in spite of the queen’s orders to make no terms with the rebels. After some negotiation the parties concluded an armistice and agreed on capitulation (onorevole capitolazione), whereby the castles were to be evacuated, the hostages liberated and the garrisons free to remain in Naples unmolested or to sail for Toulon.

While the vessels were being prepared for the voyage to Toulon all the hostages in the castles were liberated save four; but on 24 June 1799 Nelson arrived with his fleet, and on hearing of the capitulation he refused to recognise it except insofar as it concerned the French.

Ruffo indignantly declared that once the treaty was signed, not only by himself but by the Russian and Turkish commandants and by the British Captain Edward Foote, it must be respected, and on Nelson’s refusal he said that he would not help him to capture the castles. On 26 June 1799 Nelson changed his attitude and authorised Sir William Hamilton, the British minister, to inform the cardinal that he (Nelson) would do nothing to break the armistice; while Captains Bell and Troubridge wrote that they had Nelson’s authority to state that the latter would not oppose the embarcation of the Republicans. Although these expressions were equivocal, the Republicans were satisfied and embarked on the vessels prepared for them. However, on 28 June Nelson received despatches from the court (in reply to his own), in consequence of which he had the vessels brought under the guns of his ships, and many of the Republicans were arrested. Caracciolo, who had been caught whilst attempting to escape from Naples, was tried by a court-martial of Royalist officers under Nelson’s auspices on board the admiral's flagship, condemned to death and hanged at the yard arm.

Aftermath

On 10 July 1799, King Ferdinand entered the bay of Naples on a Neapolitan frigate, the Sirena. At four o'clock that afternoon, he went aboard the British Foudroyant, which was to be his headquarters for the next four weeks.[2]

Of some 8,000 political prisoners, 99 were executed, including Prince Gennaro Serra, who was publicly beheaded, and others, such as the intellectual Mario Pagano who had written the republican constitution; the scientist Domenico Cirillo; Luisa Sanfelice; Gabriele Manthoné, the minister of war under the republic; Massa, the defender of Castel dell'Ovo; Ettore Carafa, the defender of Pescara, who had been captured by treachery; and Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel, court-poet turned revolutionary and editor of il Monitore Napoletano, the newspaper of the republican government. More than 500 other people were imprisoned (222 for life), 288 were deported and 67 exiled.[2] The subsequent censorship and oppression of all political movement was far more debilitating for Naples.

After these events were reported in Britain, Charles James Fox denounced Nelson in the House of Commons for the admiral's part in "the atrocities at the Bay of Naples".

See also

References

- ^ Davis, John (2006). Naples and Napoleon: Southern Italy and the European Revolutions, 1780-1860. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198207559.

- ^ a b c Acton, Harold (1957). The Bourbons of Naples (1731-1825) (2009 ed.). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571249015.

- ^ Between Salt Water And Holy Water: A History Of Southern Italy, By Tommaso Astarita, page 250

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Further reading

- Acton, Harold. The Bourbons of Naples (1731-1825) (2009)

- Davis, John. Naples and Napoleon: Southern Italy and the European Revolutions, 1780-1860 (Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780198207559)

- Gregory, Desmond. Napoleon's Italy (2001)

- Client states of the Napoleonic Wars

- Former countries on the Italian Peninsula

- Former republics

- 18th-century in Naples

- History of Salerno

- Early Modern Italy

- States and territories established in 1799

- States and territories disestablished in 1799

- 1799 establishments in Italy

- 1799 disestablishments in Italy

- 1799 in Italy