Personal relationships of Alexander the Great

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (April 2020) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early rule

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Expedition into India

Death and legacy

Cultural impact

|

||

The historical and literary tradition describes several of Alexander's relations, some of which are the subject of question among modern historians.

Relationships

[edit]

Curtius reports, "He scorned sensual pleasures to such an extent that his mother was anxious lest he be unable to beget offspring." To encourage a relationship with a woman, King Philip and Olympias were said to have brought in a high-priced Thessalian courtesan named Callixena. According to Athenaeus, Callixena was employed by Olympias out of fear that Alexander was "womanish" (γύvνις), and his mother used to beg him to sleep with the courtesan, apparently to no success.[1][2][3] Some modern historians, such as James Davidson, see this as evidence of Alexander's homosexuality.[2] Two ancient historians, Siculus and Curtius, tell of him spending thirteen days with a tribe-leader of woman-warriors hailing from the Caucasus Mountains, however this appears alongside many other hyperbolized aspects of his character and achievements, and ancient historians did not distinguish between myth and history in the same way we do today.[4]

Ancient authors see this and other anecdotes as proof of Alexander's self-control in regards to sensual pleasures, and accounts are also known of Alexander's stern refusal to accept indiscreet offers from men who tried to pimp him male prostitutes, among whom, according to Aeschines and Hypereides, was the renowned Athenian orator Demosthenes. According to Carystius (as quoted by Athenaeus), when Alexander praised the beauty of a boy at a gathering, probably a slave belonging to one Charon of Chalcis, the latter asked the boy to kiss Alexander, but Alexander refused, to spare Charon the embarrassment of having to share his boy's affections.[5]

According to Plutarch, the only woman with whom Alexander had sex before his first marriage was Barsine, daughter of Artabazos II of Phrygia but of Greek education. There is speculation that he may have fathered a child, Heracles, of her in 327 BC. Mary Renault, however, was sceptical of such a story:

No record at all exists of such a woman accompanying his march; nor of any claim by her, or her powerful kin, that she had born him offspring. Yet twelve years after his death a boy was produced, seventeen years old...a claimant and shortlived pawn in the succession wars...no source reports any notice whatever taken by him of a child who, Roxane's being posthumous, would have been during his lifetime his only son, by a near-royal mother. In a man who named cities after his horse and dog, this strains credulity.[6]

Regardless, ancient reports state that Alexander and Barsine became lovers, as Alexander was enthralled by her beauty and knowledge of Greek literature.[4]

Alexander married three times: to Roxana of Bactria, Stateira, and Parysatis, daughter of Ochus. He fathered at least one child, Alexander IV of Macedon, born by Roxana shortly after his death in 323 BC.

Metz Epitome contains report that Roxana and Alexander had another child before having their son - a baby who was born in India and died there, in November 326 BC.[7]

There is speculation that Stateira could have been pregnant when she died; if so, she and her child played no part in the succession battles which ensued after his death, as Roxana ordered Stateira's death.

Diodorus Siculus writes, "Then he put on the Persian diadem and dressed himself in the white robe and the Persian sash and everything else except the trousers and the long-sleeved upper garment. He distributed to his companions cloaks with purple borders and dressed the horses in Persian harness. In addition to all this, he added concubines to his retinue in the manner of Darius, in number not less than the days of the year and outstanding in beauty as selected from all the women of Asia. Each night these paraded about the couch of the king so that he might select the one with whom he would lie that night. Alexander, as a matter of fact, employed these customs rather sparingly and kept for the most part to his accustomed routine, not wishing to offend the Macedonians."[8]

According to Plutarch, Alexander once sought a sexual encounter with Theodorus's music girl, saying to him that "if you don't have lust for your music-girl, send her to me for ten talents."[9]

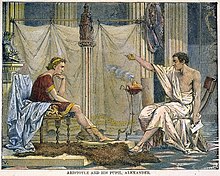

Aristotle

[edit]

Aristotle was the head of the royal academy of Macedon and, in 343 BC, Philip II of Macedon invited him to serve as the tutor for the prince, Alexander.[10] Alexander received inspiration for his eastward conquests, as Aristotle was encouraged to become: "a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians, to look after the former as after friends and relatives, and to deal with the latter as with beasts or plants". Aristotle held ethnocentric views against Persia, which estranged him and Alexander as the latter adopted a few of the Persian royal customs and clothing. This tension led to ancient rumors that painted Aristotle as a suspect for Alexander’s death, but this rumor spread based on a single claim made six years after Alexander’s passing.[11]

Alexander also received his primary education on the Persian customs and traditions through Aristotle. Aristotle’s tutelage is also attributed as the reason why Alexander brought an entourage of zoologists, botanists, philosophers, and other researchers on his expeditions deep into the east. Through those expeditions Alexander discovered that much of the geography he learned from Aristotle was plainly wrong. Upon Aristotle’s publication of his geographic work, Alexander lamented:[12]

Hephaestion

[edit]

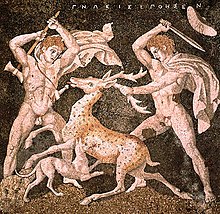

Alexander had a close emotional attachment to his companion, cavalry commander (hipparchus) and childhood friend, Hephaestion. He studied with Alexander, as did a handful of other children of Ancient Macedonian aristocracy, under the tutelage of Aristotle. Hephaestion makes his appearance in history at the point when Alexander reaches Troy. There they made sacrifices at the shrines of the two heroes Achilles and Patroclus; Alexander honouring Achilles, and Hephaestion honouring Patroclus.

After Hephaestion's death in Oct 324 BC, Alexander mourned him greatly and did not eat for days. Alexander held an elaborate funeral for Hephaestion at Babylon, and sent a note to the shrine of Ammon, which had previously acknowledged Alexander as a god, asking them to grant Hephaestion divine honours. The priests declined, but did offer him the status of divine hero. Alexander died soon after receiving this letter; Mary Renault suggests that his grief over Hephaestion's death had led him to be careless with his health. Alexander was overwhelmed by his grief for Hephaestion, so much that Arrian records that Alexander "flung himself on the body of his friend and lay there nearly all day long in tears, and refused to be parted from him until he was dragged away by force by his Companions".[13]

Nature of relationship

[edit]Although none of the five main sources of Alexander's life state that there was anything other than friendship between Alexander and Hephaestion, historians speculate that there was more. Robin Lane Fox states that the two were possibly lovers, elaborating that "later gossip claimed that Alexander [and Hephaestion] had a love affair. No contemporary history states this, but the facts show that the two men's friendship was exceptionally deep and close."[14] Paul Cartledge writes that the two "almost certainly" physically expressed their love at one or more stages in their lives.[15] Cartledge notes that if Hephaestion was Alexander's "catamite", the stigma attached to being the passive sexual partner is not something that Hephaestion would have wished to boast about.[15]

In Alexander the Great: Sources and studies, William Woodthorpe Tarn wrote, "There is then not one scrap of evidence for calling Alexander homosexual."[16] Ernst Badian rejects Tarn's portrait of Alexander, stating that Alexander was closer to a ruthless dictator and that Tarn's depiction was the subject of personal bias.[17] Cartledge states that any attempt to "expunge all trace, or taint, of homosexuality" from Alexander and Hephaestion's relationship are "seriously misguided."[15]

Campaspe

[edit]Campaspe, also known as Pancaste, is thought to have been a prominent citizen of Larissa in Thessaly, and may have been the mistress of Alexander. If this is true, she was one of the first women with whom Alexander was intimate; Aelian even surmises that it was to her that a young Alexander lost his virginity.

One story tells that Campaspe was painted by Apelles, who enjoyed the reputation in Antiquity for being the greatest of painters. The episode occasioned an apocryphal exchange that was reported in the sources for the life of Alexander in Pliny's Natural History. Robin Lane Fox traces her legend back to the Roman authors Pliny the Elder, Lucian of Samosata and Aelian's Varia Historia.

Campaspe became a generic poetical pseudonym for a man's mistress.

Barsine

[edit]Barsine was a noble Greek-Persian, daughter of Artabazus, and wife of Memnon. After Memnon's death, several ancient historians have written of a love affair between her and Alexander. Plutarch writes, "At any rate Alexander, so it seems, thought it more worthy of a king to subdue his own passions than to conquer his enemies, and so he never came near these women, nor did he associate with any other before his marriage, with the exception only of Barsine. This woman, the widow of Memnon, the Greek mercenary commander, was captured at Damascus. She had received a Greek education, was of a gentle disposition, and could claim royal descent, since her father was Artabazus who had married one of the Persian king's daughters. These qualities made Alexander the more willing he was encouraged by Parmenio, so Aristobulus tells us to form an attachment to a woman of such beauty and noble lineage."[18] In addition Justin writes, "As he afterwards contemplated the wealth and display of Darius, he was seized with admiration of such magnificence. Hence it was that he first began to indulge in luxurious and splendid banquets, and fell in love with his captive Barsine for her beauty, by whom he had afterwards a son that he called Heracles."[19]

The story may be true, but if so, it raises some difficult questions. The boy would have been Alexander's only child born during his lifetime (Roxane's son was born posthumously). Even if Alexander had ignored him, which seems highly unlikely, the Macedonian Army and the successors would certainly have known of him, and would almost certainly have drawn him into the succession struggles which ensued upon Alexander's death. Yet we first hear of the boy twelve years after Alexander's death, when a boy was produced as a claimant to the throne. Especially since Alexander's own half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (Philip II's illegitimate and physically and mentally disabled son[20]) was Alexander's original successor.[21] Alexander's illegitimate son would have had more rights to the throne than his illegitimate[22] half-brother. Heracles played a brief part in the succession battles, and then disappeared. It seems more likely that the romance with Barsine was invented by the boy's backers to validate his parentage.[23]

Roxana

[edit]

Ancient historians, as well as modern ones, have also written on Alexander's marriage to Roxana the beautiful [Persian] woman. Robin Lane Fox writes, "Roxana was said by contemporaries to be the most beautiful lady in all Asia. She deserved her name of Roshanak, meaning 'little star', (probably rokhshana or roshana which means light and illuminating) in Persian. Marriage to a local noble's family made sound political sense, but contemporaries implied that Alexander, aged 28, also lost his heart. A wedding-feast for the two of them was arranged high on one of the Persian rocks. Alexander and his bride shared a loaf of bread, a custom still observed in Turkestan. Characteristically, Alexander sliced it with his sword.[24] Ulrich Wilcken writes, "The fairest prize that fell to him was Roxana, the daughter of Oxyartes, in the first bloom of youth, and in the judgment of Alexander's companions, next to Stateira the wife of Darius, the most beautiful woman that they had seen in Asia. Alexander fell passionately in love with her and determined to raise her to the position of his consort."[25]

As soon as Alexander died in 323 BC, Roxana murdered Alexander's two other wives. Roxana wished to cement her own position and that of her son, unborn at that time, by ridding herself of a rival who could be — or claim to be — pregnant. According to Plutarch's account, Stateira's sister, Drypetis, was murdered at the same time; Carney believes that Plutarch was mistaken, and it was actually Parysatis who died with Stateira.[26]

Roxana bore Alexander a posthumous child also named Alexander (Alexander IV), 2 months after Alexander the Great died.

Bagoas

[edit]Ancient sources tell of another favourite, Bagoas; a eunuch "in the very flower of boyhood, with whom Darius was intimate and with whom Alexander would later be intimate."[27] Plutarch recounts an episode (also mentioned by Dicaearchus) during some festivities on the way back from India in which his men clamor for him to kiss the young man: "We are told, too, that he was once viewing some contests in singing and dancing, being well heated with wine, and that the Macedonians' favourite, Bagoas, won the prize for song and dance, and then, all in his festal array, passed through the theatre and took his seat by Alexander's side; at sight of which the Macedonians clapped their hands and loudly bade the king kiss the victor, until at last he threw his arms about him and kissed him tenderly." Athenaeus tells a slightly different version of the story — that Alexander kissed Bagoas in a theatre and, as his men shouted in approval, he repeated the action.[28]

The Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus was highly critical of the relationship between Alexander and Bagoas, saying that Alexander was seized of such desire by the eunuch, that Bagoas became the de facto sovereign of Persia, exploiting Alexander's affections to make him persecute Bagoas's personal enemies, such as the Persian governor Orxines.[29]

A 1972 novel by Mary Renault, The Persian Boy, chronicles that story with Bagoas as narrator [30] Renault wrote disparagingly of Rufus's reliability, stating: "[Rufus's account of Alexander] is bent that way by recourse to Athenian anti-Macedonian agitprop, written by men who never set eyes on him, and bearing about as much relation to objective truth as one would expect to find in a History of the Jewish People commissioned by Adolf Hitler."[31]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Athenaeus. "Deipnosophistae, book 10".

- ^ a b Konstantinos Kapparis (2018). Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World. De Gruyter. p. 115. ISBN 978-3110556759.

- ^ Richard A. Gabriel (2010). Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander. University of Nebraska Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1597975193.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas R (2012). Alexander the Great: the story of an ancient life. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0521148443.

- ^ Thomas K. Hubbard, ed. (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0520234307.

- ^ Renault, pp. 110.

- ^ Metz Epitome 70

- ^ Diodorus XVII.77.5

- ^ Rist, John M. (December 2001). "Plutarch's Amatorius: A Commentary on Plato's Theories of Love?". The Classical Quarterly. 51 (2): 557–575. doi:10.1093/cq/51.2.557. ISSN 1471-6844.

- ^ Shields, Christopher (2016). "Aristotle's Psychology". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.).

- ^ Green, Peter (1991). Alexander of Macedon. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27586-7.

- ^ "Plutarch – Life of Alexander (Part 1 of 7)". penelope.uchicago.edu. Loeb Classical Library. 1919. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Arrian 7.14.13

- ^ Fox (1980)

- ^ a b c Cartledge 2004, p.205

- ^ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (1948). Alexander the Great: Sources and studies. p. 323..

- ^ Eugene N. Borza, Collected papers on Alexander the Great, pp. ii, xiv, xv.

- ^ "Caratini, p. 170.

- ^ Justinius 9.10.

- ^ "Philip Arrhidaeus - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ Curtius Rufus, Quintus (1946). History of Alexander the Great of Macedonia (in Latin and English). Translated by Rolfe, John Carew. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 543.

- ^ "The election of Arrhidaeus - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ Renault, pp. 110–11.

- ^ Fox (1980), p. 298.

- ^ Wilcken.

- ^ Carney (2000), p. 110.

- ^ Rufus, VI.5.23.

- ^ Deipnosophistae, 13d.

- ^ Joseph Roisman (2014). "Chapter 24: Greek and Roman Ethnosexuality". In Hubbard, Thomas (ed.). A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 407. ISBN 978-1-4051-9572-0.

- ^ Renault, Mary (2003). The Persian Boy. Arrow Books. ISBN 9780099463481..

- ^ Tougher, Sean (2008). "The Renault Bagoas: The Treatemnet of Alexander the Great's Eunuch in Mary Renault's The Persian Boy" (PDF). New Voices in Classical Reception Studies (3): 77–89. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

References

[edit]- Primary sources:

- Justinus, Junianus, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus

- Rufus, Quintus Curtius, Historiae Alexandri Magni.

- Secondary sources:

- Cartledge, Paul. "Alexander the Great: hunting for a new past?" History Today, 54 (2004).

- Cartledge, Paul. Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past. Woodstock, NY; New York: The Overlook Press, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 1-58567-565-2); London: PanMacmillan, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4050-3292-8); New York: Vintage, 2005 (paperback, ISBN 1-4000-7919-5).

- Fox, Robin Lane, The Search for Alexander, Little Brown & Co. Boston, 1st edition (October 1980). ISBN 0-316-29108-0.

- Fox, Robin Lane, "Riding with Alexander" Archaeology, September 14, 2004.

- Daniel Ogden, Alexander the Great: Myth, Genesis, and Sexuality. University of Exeter Press, 2011.

- Renault, Mary. The Nature of Alexander, 1st American edition (November 12, 1979), Pantheon Books ISBN 0-394-73825-X.

- Wilcken, Ulrich, Alexander the Great, W. W. Norton & Company; Reissue edition (March 1997). ISBN 0-393-00381-7.